Uniform Circular Motion

A particle is in uniform circular motionif it travels around a circle or a circular arc at constant (uniform) speed. Although the speed does not vary, the particle is accelerating. That fact may be surprising because we often think of acceleration (a change in velocity) as an increase or decrease in speed. However, actually velocity is a vector, not a scalar. Thus, even if a velocity changes only in direction, there is still an acceleration, and that is what happens in uniform circular motion.

|

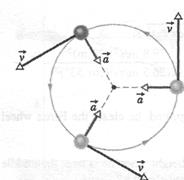

Figure 4-18 shows the relation between the velocity and acceleration vectors at various stages during uniform circular motion. Both vectors have constant magnitude as the motion progresses, but their directions change continuously. The velocity is always directed tangent to the circle in the direction of motion. The acceleration is always directed radially inward. Because of this, the acceleration associated with uniform circular motion is called a centripetal (meaning "center seeking") acceleration.As we prove next, the magnitude of this acceleration  is

is

(centripetal acceleration) (4-32)

(centripetal acceleration) (4-32)

where  is the radius of the circle and

is the radius of the circle and  is the speed of the particle.

is the speed of the particle.

In addition, during this acceleration at constant speed, the particle travels the circumference of the circle (a distance of  ) in time

) in time

(period). (4-33)

(period). (4-33)

is called the period of revolution, or simply the period, of the motion. It is, in general, the time for a particle to go around a closed path exactly once.

is called the period of revolution, or simply the period, of the motion. It is, in general, the time for a particle to go around a closed path exactly once.

Proof of Eq. 4-32

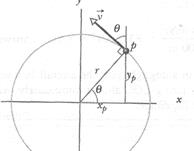

To find the magnitude and direction of the acceleration for uniform circular motion, we consider Fig. 4-19. In Fig. 4-l9a, particle p moves at constant speed  around a circle of radius

around a circle of radius  . At the instant shown, p has coordinates

. At the instant shown, p has coordinates  and

and  .

.

|

Recall from Section 4-3 that the velocity  of a moving particle is always tangent to the particle's path at the particle's position. In Fig. 4-19a, that means

of a moving particle is always tangent to the particle's path at the particle's position. In Fig. 4-19a, that means  is perpendicular to a radius

is perpendicular to a radius  drawn to the particle's position. Then the angle

drawn to the particle's position. Then the angle  that

that  makes with a vertical at p equals the angle

makes with a vertical at p equals the angle  that radius

that radius  makes with the

makes with the  axis.

axis.

The scalar components of  are shown in Fig. 4-19b. With them, we can write the velocity

are shown in Fig. 4-19b. With them, we can write the velocity  as

as

|

(4-34)

(4-34)

Now, using the right triangle in Fig. 4-19a, we can replace  with

with  and

and  with

with  to write

to write

(4-35)

(4-35)

To find the acceleration  of particle p, we must take the time derivative of this equation. Noting that speed

of particle p, we must take the time derivative of this equation. Noting that speed  and radius

and radius  do not change with time, we obtain

do not change with time, we obtain

(4-36)

(4-36)

Now note that the rate

Now note that the rate  at which

at which  changes is equal to the velocity component

changes is equal to the velocity component  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  , and, again from Fig. 4-19b, we see that

, and, again from Fig. 4-19b, we see that  and

and  . Making these substitutions in Eq. 4-36, we find

. Making these substitutions in Eq. 4-36, we find

(4-37)

(4-37)

This vector and its components are shown in Fig. 4-19c. Following Eq. 3-6, we find that the magnitude of  is

is

as we wanted to prove. To orient

as we wanted to prove. To orient  , we can find the angle

, we can find the angle  shown in Fig. 4-19c:

shown in Fig. 4-19c:

Thus,  , which means that

, which means that  is directed along the radius

is directed along the radius  of Fig. 4-19a toward the circle's center, as we wanted to prove.

of Fig. 4-19a toward the circle's center, as we wanted to prove.

Sample Problem 4-9

Sample Problem 4-9

"Top gun" pilots have long worried about taking a turn too tightly. As a pilot's body undergoes centripetal acceleration, with the head toward the center of curvature, the blood pressure in the brain decreases, leading to loss of brain function.

There are several warning signs to signal a pilot to ease up: when the centripetal acceleration is  or

or  , the pilot feels heavy. At about

, the pilot feels heavy. At about  , the pilot's vision switches to black and white and narrows to "tunnel vision." If that acceleration is sustained or increased, vision ceases and, soon after, the pilot is unconscious - a condition known as

, the pilot's vision switches to black and white and narrows to "tunnel vision." If that acceleration is sustained or increased, vision ceases and, soon after, the pilot is unconscious - a condition known as  -LOC for "

-LOC for "  -induced loss of consciousness." What is the centripetal acceleration, in

-induced loss of consciousness." What is the centripetal acceleration, in  units, of a pilot flying an F-22 at speed

units, of a pilot flying an F-22 at speed  = 2500 km/h (694 m/s) through a circular arc with radius of curvature

= 2500 km/h (694 m/s) through a circular arc with radius of curvature  = 5.80 km?

= 5.80 km?

SOLUTION: The Key Idea here is that although the pilot's speed is constant, the circular path requires a (centripetal) acceleration, with magnitude given by Eq. 4-32:

(Answer)

(Answer)

If an unwary pilot caught in a dogfight puts the aircraft into such a tight turn, the pilot goes into  -LOC almost immediately, with no warning signs to signal the danger.

-LOC almost immediately, with no warning signs to signal the danger.

Velocity and Coordinate by Integration

When  varies with time, we can use the relation

varies with time, we can use the relation  to find the velocity

to find the velocity  as a function of time if the position

as a function of time if the position  is a given function of time. Similarly, we can use

is a given function of time. Similarly, we can use  to find the acceleration

to find the acceleration  as a function of time if the velocity

as a function of time if the velocity  is a given function of time.

is a given function of time.

We can also reverse this process. Suppose  is known as a function of time; how can we find

is known as a function of time; how can we find  as a function of time? To answer this question, we first

as a function of time? To answer this question, we first

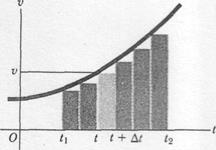

Fig.3 The area under a velocity-time graph equals the displacement

Fig.3 The area under a velocity-time graph equals the displacement

|

consider a graphical approach. Figure 3 shows a velocity-versus-time curve for a situation where the acceleration (the slope of the curve) is not constant but increases with time. Considering the motion during the interval between times  and

and  , we divide this total interval into many smaller intervals, calling a typical one

, we divide this total interval into many smaller intervals, calling a typical one  . Let the velocity during that interval be

. Let the velocity during that interval be  . Of course, the velocity changes during

. Of course, the velocity changes during  , but if the interval is very small, the change will also be very small. This displacement during that interval, neglecting the variation of

, but if the interval is very small, the change will also be very small. This displacement during that interval, neglecting the variation of  , is given by

, is given by

.

.

This corresponds graphically to the area of the shaded strip with height  and width

and width  , that is, the area under the curve corresponding to the interval

, that is, the area under the curve corresponding to the interval  . Since the total displacement in any interval (say,

. Since the total displacement in any interval (say,  to

to  )is the sum of the displacements in the small subintervals, the total displacement is given graphically by the total area under the curve between the vertical lines

)is the sum of the displacements in the small subintervals, the total displacement is given graphically by the total area under the curve between the vertical lines  and

and  . In the limit, when all the

. In the limit, when all the  become very small and their number very large, this is simply the integral of

become very small and their number very large, this is simply the integral of  (which is in general a function of

(which is in general a function of  )from

)from  and

and  . Thus

. Thus  is the position at time

is the position at time  and

and  the position at time

the position at time  :

:

(2-14)

(2-14)

A similar analysis with the acceleration-versus-time curve, where  is in general a function of

is in general a function of  , shows that if

, shows that if  is the velocity at time

is the velocity at time  and

and  the velocity at time

the velocity at time  , the change in velocity

, the change in velocity  during a small time interval

during a small time interval  is approximately equal to

is approximately equal to  , and the total change in velocity (

, and the total change in velocity (  )during the interval

)during the interval  is given by

is given by

Or, finally,  .

.

Exercises

1. Velocity of a body, moving in viscous medium, is given by the equation  , where

, where  - initial velocity,

- initial velocity,  - constant. What are the distance and acceleration as function of time?

- constant. What are the distance and acceleration as function of time?

2. A particle moves along a straight line with velocity  , where

, where  is constant. If at time

is constant. If at time  the distance, traveled the particle was

the distance, traveled the particle was  , determine: (a) dependence of speed and acceleration on time (

, determine: (a) dependence of speed and acceleration on time (  and

and  )

)

3. (a) If particle’s acceleration is given by  , (where

, (where  is in meter/second2 and

is in meter/second2 and  in seconds), what its velocity at

in seconds), what its velocity at  ? (b) What is its coordinate at

? (b) What is its coordinate at  s?

s?

Дата добавления: 2015-06-17; просмотров: 1373;