Brain and Emotion

The opinion of visual systems and the hints of earworms are interesting and motivating, but we can’t just take them at their word. In order to make a solid case that music sounds like human movement, I need to show that the music‑is‑movement theory can leap the four hurdles we discussed earlier: “brain,” “emotion,” “dance,” and “structure.” Let’s begin in this section with the first two.

For the “brain” hurdle, I need to say why our brain would have mechanisms for making sense of music and responding to it so eagerly and intricately. For the theory that music sounds like human movement, then, we must ask ourselves if it is plausible that we have brain mechanisms for processing the sounds of humans doing stuff. The answer is yes. Of course we have humans‑doing‑stuff auditory mechanisms! The most important animals in the life of any animal are its conspecifics (other animals of the same species), and so our brains are well equipped to communicate with and “read” our fellow humans. Face recognition is one familiar example, and color vision, with its ability to detect emotional signals on the skin, is another one (which I discussed in detail in my previous book, The Vision Revolution ). It would be bizarre if we had no specialized auditory mechanisms for sensing the sounds of other people carrying out behaviors. Actions speak louder than words–the sounds we make when we act are often a dead giveaway to what we’re up to. And we’ve been making sounds when we move for many millions of years, plenty long enough to have evolved such mechanisms. The music‑sounds‑like‑movement hypothesis, then, can make a highly plausible case that it satisfies the “brain” hurdle. Our brains surely have evolved to possess specialized mechanisms to hear what people are doing.

How about the second hurdle for a theory of music, the one labeled “emotion”? Could the mundane sounds of people moving underlie our love affair with music? As we discussed at the start of the chapter, music is evocative–it can sound joyous, aggressive, melancholy, amorous, tortured, strong, lethargic, and so on. I said then that the evocative nature of music suggests that it must be “made out of people.” Human movement is , obviously, made of and by people, but can human movement truly be evocative? Of course! The ability to infer emotional states from the bodily movements of others comes via several routes. First and foremost, when people carry out behaviors they move their bodies, movements that can give away what the person is doing; knowing what the person is doing can, in turn, be crucial for understanding the actor’s emotion or mood. Second, the actor’s emotional state is often cued by its side effects on behavior, such as when an exhausted person staggers. And third, some bodily movements serve as direct emotional signals, more akin to facial expressions and color signals: bodily movements can be proud, strutting, threatening, ebullient, jaunty, sulking, arrogant, inviting, and so on. Human movement can, then, certainly be evocative. And unlike evocative facial expressions and skin color signals, which are silent, our evocative bodily expressions and movements make noises. The sounds of human movement not only are “made from people,” then, but they can be truly evocative, fulfilling the “emotion” hurdle.

An example will help to clarify how the sounds of human movement can be emotionally evocative. Michael Zampi, then an undergraduate at RPI, was interested in uncovering the auditory cues for happy, sad, and angry walkers. He first noted that University of Tübingen researchers Claire L. Roether, Lars Omlor, Andrea Christensen, and Martin A. Giese had observed that happy walkers tend to lean back and have large arm and leg swings, angry walkers lean forward and have large arm and leg swings, and sad walkers tend to lean forward and have attenuated arm and leg swings.

“What,” Michael asked, “are the distinctive sounds for those three gaits?” He reasoned that leaning back leads to a larger gap between the sound of the heel and the sound of the toe. And, furthermore, larger arm and leg swings tend to lend greater emphasis to any sounds made by the limbs in between the footsteps (later I will refer to these sounds as “banging ganglies”). Given this, Michael could conclude that happy walkers have long heel‑toe gaps and loud between‑the‑steps gait sounds; angry walkers have short heel‑toe temporal gaps and loud between‑the‑steps gait sounds; and sad walkers have short heel‑toe gaps and soft between‑the‑steps gait sounds. But are these cues sufficient to elicit the perception that a walker is happy, angry, or sad?

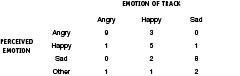

Michael created simple rhythms, each with three drum strikes per beat: a toe‑strike on the beat, a heel strike just before the beat, and a between‑the‑step hit on the off‑beat. Starting from a baseline audio track–an intermediate heel‑toe gap and a between‑the‑steps sound with intermediate emphasis–Michael created versions with shorter and longer heel‑toe gaps, and versions with less emphasized and more emphasized between‑the‑steps sounds. Listeners were told they would hear the sounds of people walking in various emotional states, and then the listeners were presented with the baseline stimulus, followed by one of the four modulations around it. They were asked to volunteer an emotion term to describe the modulated gait. As can be seen in Figure 17, subjects had a tendency to perceive the simulated walker’s emotion accurately.

Figure 17 . Each column is for one of the three tracks having the sounds modulating around the baseline to indicate the labeled emotion. The numbers show how many subjects volunteered the emotions “angry,” “happy,” “sad,” or other emotions words for each of the three tracks. One can see that the most commonly perceived emotion in each column matches the gait’s emotion.

This pilot study of Michael Zampi’s is just the barest beginning in our attempts to make sense of the emotional cues in the sounds of people moving. The hope is that by understanding these cues, we can better understand how music modulates emotion, and perhaps why genres differ in their emotional effects.

If music has been culturally selected to sound like human movement, then it is easy to see why we’d have a brain for it, and easy to see why music can be so emotionally moving. But why should music be so motionally moving? The music‑is‑movement theory has to explain why the sounds of people moving should impel other people to move. That’s the third hurdle over which we must leap: the “dance” hurdle, which we take up next.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1241;