Position and Displacement

One general way of locating a particle (or particle-like object) is with a position vector , which is a vector that extends from a reference point (usually the origin of a coordinate system) to the particle. In the unit-vector notation,

, which is a vector that extends from a reference point (usually the origin of a coordinate system) to the particle. In the unit-vector notation,  can be written

can be written

, (4-1)

, (4-1)

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the vector components of

are the vector components of  , and the coefficients

, and the coefficients  ,

,  , and

, and  are its scalar components.

are its scalar components.

The coefficients  ,

,  , and

, and  give the particle's location along the coordinate axes and relative to the origin; that is, the particle has the rectangular coordinates (

give the particle's location along the coordinate axes and relative to the origin; that is, the particle has the rectangular coordinates (  ,

,  ,

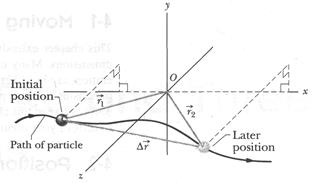

,  ). For instance, Fig. 4-1 shows a particle with position vector

). For instance, Fig. 4-1 shows a particle with position vector

(4-2)

(4-2)

Fig. 4-1

Fig. 4-1

|

and rectangular coordinates  . Along the

. Along the  axis the particle is 3 m from the origin, in the

axis the particle is 3 m from the origin, in the  direction. Along the

direction. Along the  axis it is 2 m from the origin, in the

axis it is 2 m from the origin, in the  direction. Along the

direction. Along the  axis it is 5 m from the origin, in the

axis it is 5 m from the origin, in the  direction.

direction.

As a particle moves, its position vector changes in such a way that the vector always extends to the particle from the reference point (the origin). If the position vector changes, say, from  to

to  during a certain time interval, then the particle's displacement

during a certain time interval, then the particle's displacement during that time interval is

during that time interval is

(4-2)

(4-2)

Using the unit-vector notation, we can rewrite this displacement as

or as

(4-3)

(4-3)

where coordinates (  ,

,  ,

,  ) correspond to position vector

) correspond to position vector  and coordinates (

and coordinates (  ,

,  ,

,  )correspond to position vector

)correspond to position vector  . We can also rewrite the displacement by substituting

. We can also rewrite the displacement by substituting  for

for  ,

,  for

for  , and

, and  for

for  :

:

(4-3)

(4-3)

Example 4-1

In Fig. 4-2, the position vector for a particle is initially

Fig. 4-2

Fig. 4-2

|

and then later is

.

.

What is the particle's displacement  from

from  to

to  ?

?

Solution. The Key Ideais that the displacement  is obtained by subtracting the initial position vector

is obtained by subtracting the initial position vector  from the later position vector

from the later position vector  . That is most easily done by components:

. That is most easily done by components:

(Answer)

(Answer)

This displacement vector is parallel to the  plane, because it lacks any

plane, because it lacks any  component, a fact that is easier to see in the numerical result than in Fig. 4-2.

component, a fact that is easier to see in the numerical result than in Fig. 4-2.

Дата добавления: 2015-06-17; просмотров: 812;