III. The Rocky Shores 5 страница

The lives of many of these creatures of the low‑tide rocks are bound together by interlacing ties, in the relation of predator to prey, or in the relation of species that compete for space or food. Over all these the sea itself exercises a directing and regulating force.

The urchins seek sanctuary from the gulls at this low level of the spring tides, but in themselves stand in the relation of dangerous predators to other animals. Where they advance into the Irish moss zone, hiding in deep crevices and sheltering under rock overhangs, they devour numbers of periwinkles, and even attack barnacles and mussels. The number of urchins at any particular level of shore has a strong regulating effect on the populations of their prey. The starfish and a voracious snail, the common whelk, like the urchins, have their centers of population in deep water offshore and make predatory excursions of varying duration into the intertidal zone.

The position of the prey animals–the mussels, barnacles, and periwinkles–on sheltered shores has become difficult. They are hardy and adaptable, able to live at any level of the tide. Yet on such shores the rockweeds have crowded them out of the upper two‑thirds of the shore, except for scattered individuals. At and just below the low‑tide line are the hungry predators, so all that remains for these animals is the level near the low‑water line of the neap tides. On protected coasts it is here that the barnacles and mussels assemble in their millions to spread their cover of white and blue over the rocks, and the legions of the common periwinkle gather.

But the sea, with its tempering and modifying effect, can alter the pattern. Whelks, starfish, and urchins are creatures of cold water. Where the offshore waters are cold and deep and the tidal flow is drawn from these icy reservoirs, the predators can range up into the intertidal zone, decimating the numbers of their prey. But when there is a layer of warm surface water the predators are confined to the cold deep levels. As they retreat seaward, the legions of their prey follow down in their wake, descending as far as they may into the world of the low spring tides.

Tide pools contain mysterious worlds within their depths, where all the beauty of the sea is subtly suggested and portrayed in miniature. Some of the pools occupy deep crevices or fissures; at their seaward ends these crevices disappear under water, but toward the land they run back slantingly into the cliffs and their walls rise higher, casting deep shadows over the water within them. Other pools are contained in rocky basins with a high rim on the seaward side to hold back the water when the last of the ebb drains away. Seaweeds line their walls. Sponges, hydroids, anemones, sea slugs, mussels, and starfish live in water that is calm for hours at a time, while just beyond the protecting rim the surf may be pounding.

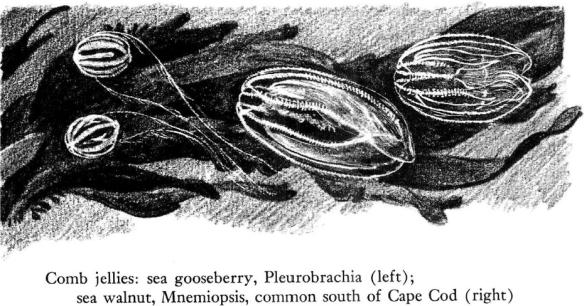

The pools have many moods. At night they hold the stars and reflect the light of the Milky Way as it flows across the sky above them. Other, living stars come in from the sea: the shining emeralds of tiny phosphorescent diatoms–the glowing eyes of small fishes that swim at the surface of the dark water, their bodies slender as matchsticks, moving almost upright with little snouts uplifted–the elusive moonbeam flashes of comb jellies that have come in with a rising tide. Fishes and comb jellies hunt the black recesses of the rock basins, but like the tides they come and go, having no part in the permanent life of the pools.

By day there are other moods. Some of the most beautiful pools lie high on the shore. Their beauty is the beauty of simple elements–color and form and reflection. I know one that is only a few inches deep, yet it holds all the depth of the sky within it, capturing and confining the reflected blue of far distances. The pool is outlined by a band of bright green, a growth of one of the seaweeds called Enteromorpha. The fronds of the weed are shaped like simple tubes or straws. On the land side a wall of gray rock rises above the surface to the height of a man, and reflected, descends its own depth into the water. Beyond and below the reflected cliff are those far reaches of the sky. When the light and one’s mood are right, one can look down into the blue so far that one would hesitate to set foot in so bottomless a pool. Clouds drift across it and wind ripples scud over its surface, but little else moves there, and the pool belongs to the rock and the plants and the sky.

In another high pool nearby, the green tube‑weed rises from all of the floor. By some magic the pool transcends its realities of rock and water and plants, and out of these elements creates the illusion of another world. Looking into the pool, one sees no water but instead a pleasant landscape of hills and valleys with scattered forests. Yet the illusion is not so much that of an actual landscape as of a painting of one; like the strokes of a skillful artist’s brush, the individual fronds of the algae do not literally portray trees, they merely suggest them. But the artistry of the pool, as of the painter, creates the image and the impression.

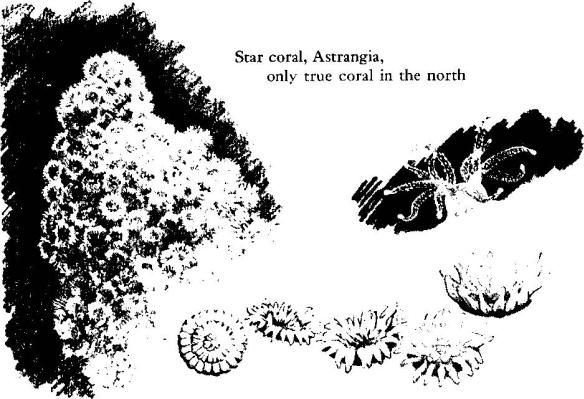

Little or no animal life is visible in any of these high pools–perhaps a few periwinkles and a scattering of little amber isopods. Conditions are difficult in all pools high on the shore because of the prolonged absence of the sea. The temperature of the water may rise many degrees, reflecting the heat of the day. The water freshens under heavy rains or becomes more salty under a hot sun. It varies between acid and alkaline in a short time through the chemical activity of the plants. Lower on the shore the pools provide far more stable conditions, and both plants and animals are able to live at higher levels than they could on open rock. The tide pools, then, have the effect of moving the life zones a little higher on the shore. Yet they, too, are affected by the duration of the sea’s absence, and the inhabitants of a high pool are very different from those of a low‑level pool that is separated from the sea only at long intervals and then briefly.

The highest of the pools scarcely belong to the sea at all; they hold the rains and receive only an occasional influx of sea water from storm surf or very high tides. But the gulls fly up from their hunting at the sea’s edge, bringing a sea urchin or a crab or a mussel to drop on the rocks, in this way shattering the hard shelly covering and exposing the soft parts within. Bits of urchin tests or crab claws or mussel shells find their way into the pools, and as they disintegrate their limy substance enters into the chemistry of the water, which then becomes alkaline. A little one‑celled plant called Sphaerella finds this a favorable climate for growth–a minute, globular bit of life almost invisible as an individual, but in its millions turning the waters of these high pools red as blood. Apparently the alkalinity is a necessary condition; other pools, outwardly similar except for the chance circumstance that they contain no shells, have none of the tiny crimson balls.

Even the smallest pools, filling depressions no larger than a teacup, have some life. Often it is a thin patch of scores of the little seashore insect, Anurida maritima– “the wingless one who goes to sea.” These small insects run on the surface film when the water is undisturbed, crossing easily from one shore of a pool to another. Even the slightest rippling causes them to drift helplessly, however, so that scores or hundreds of them come together by chance, becoming conspicuous only as they form thin, leaflike patches on the water. A single Anurida is small as a gnat. Under a lens, it seems to be clothed in blue‑gray velvet through which many bristles or hairs protrude. The bristles hold a film of air about the body of the insect when it enters the water, and so it need not return to the upper shore when the tide rises. Wrapped in its glistening air blanket, dry and provided with air for breathing, it waits in cracks and crevices until the tide ebbs again. Then it emerges to roam over the rocks, searching for the bodies of fish and crabs and the dead mollusks and barnacles that provide its food, for it is one of the scavengers that play a part in the economy of the sea, keeping the organic materials in circulation.

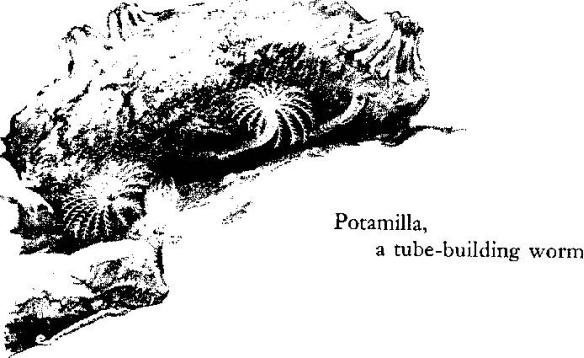

And often I find the pools of the upper third of the shore lined with a brown velvety coating. My fingers, exploring, are able to peel it off the rocks in thin smooth‑surfaced sheets like parchment. It is one of the brown seaweeds called Ralfsia; it appears on the rocks in small, lichen‑like growths or, as here, spreading its thin crust over extensive areas. Wherever it grows its presence changes the nature of a pool, for it provides the shelter that many small creatures seek so urgently. Those small enough to creep in under it–to inhabit the dark pockets of space between the encrusting weed and the rock–have found security against being washed away by the surf. Looking at these pools with their velvet lining, one would say there is little life here–only a sprinkling of periwinkles browsing, their shells rocking gently as they scrape at the surface of the brown crust, or perhaps a few barnacles with their cones protruding through the sheet of plant tissue, opening their doors to sweep the water for food. But whenever I have brought a sample of this brown seaweed to my microscope, I have found it teeming with life. Always there have been many cylindrical tubes, needle‑fine, built of a muddy substance. The architect of each is a small worm whose body is formed of a series of eleven infinitely small rings or segments, like eleven counters in a game of checkers, piled one above another. From its head arises a structure that makes this otherwise drab worm beautiful–a fanlike crown or plume composed of the finest feathery filaments. The filaments absorb oxygen and also serve to ensnare small food organisms when thrust out of the tube. And always, among this microfauna of the Ralfsia crust, there have been little fork‑tailed crustaceans with glittering eyes the color of rubies. Other crustaceans called ostracods are enclosed in flattened, peach‑colored shells fashioned of two parts, like a box with its lid; from the shell long appendages may be thrust out to row the creatures through the water. But most numerous of all are the minute worms hurrying across the crust–segmented bristle worms of many species and smooth‑bodied, serpent‑like ribbon worms or nemerteans, their appearance and rapid movements betraying their predatory errands.

A pool need not be large to hold beauty within pellucid depths. I remember one that occupied the shallowest of depressions; as I lay outstretched on the rocks beside it I could easily touch its far shore. This miniature pool was about midway between the tide lines, and for all I could see it was inhabited by only two kinds of life. Its floor was paved with mussels. Their shells were a soft color, the misty blue of distant mountain ranges, and their presence lent an illusion of depth. The water in which they lived was so clear as to be invisible to my eyes; I could detect the interface between air and water only by the sense of coldness on my fingertips. The crystal water was filled with sunshine–an infusion and distillation of light that reached down and surrounded each of these small but resplendent shellfish with its glowing radiance.

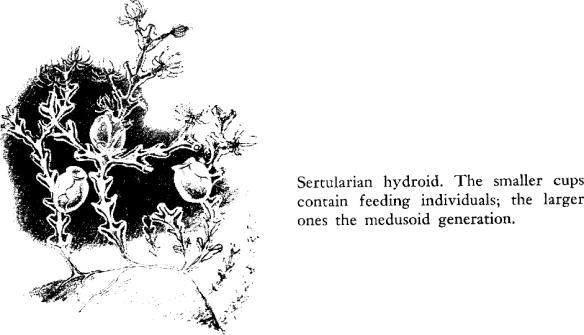

The mussels provided a place of attachment for the only other visible life of the pool. Fine as the finest threads, the basal stems of colonies of hydroids traced their almost invisible lines across the mussel shells. The hydroids belonged to the group called Sertularia, in which each individual of the colony and all the supporting and connecting branches are enclosed within transparent sheaths, like a tree in winter wearing a sheath of ice. From the basal stems erect branches arose, each branch the bearer of a double row of crystal cups within which the tiny beings of the colony dwelt. The whole was the very embodiment of beauty and fragility, and as I lay beside the pool and my lens brought the hydroids into clearer view they seemed to me to look like nothing so much as the finest cut glass–perhaps the individual segments of an intricately wrought chandelier. Each animal in its protective cup was something like a very small sea anemone–a little tubular being surmounted by a crown of tentacles. The central cavity of each communicated with a cavity that ran the length of the branch that bore it, and this in turn with the cavities of larger branches and with those of the main stem, so that the feeding activities of each animal contributed to the nourishment of the whole colony.

On what, I wondered, were these Sertularians feeding? From their very abundance I knew that whatever creatures served them as food must be infinitely more numerous than the carnivorous hydroids themselves. Yet I could see nothing. Obviously their food would be minute, for each of the feeders was of threadlike diameter and its tentacles were like the finest gossamer. Somewhere in the crystal clarity of the pool my eye–or so it seemed–could detect a fine mist of infinitely small particles, like dust motes in a ray of sunshine. Then as I looked more closely the motes had disappeared and there seemed to be once more only that perfect clarity, and the sense that there had been an optical illusion. Yet I knew it was only the human imperfection of my vision that prevented me from seeing those microscopic hordes that were the prey of the groping, searching tentacles I could barely see. Even more than the visible life, that which was unseen came to dominate my thoughts, and finally the invisible throng seemed to me the most powerful beings in the pool. Both the hydroids and the mussels were utterly dependent on this invisible flotsam of the tide streams, the mussels as passive strainers of the plant plankton, the hydroids as active predators seizing and ensnaring the minute water fleas and copepods and worms. But should the plankton become less abundant, should the incoming tide streams somehow become drained of this life, then the pool would become a pool of death, both for the mussels in their shells blue as mountains and for the crystal colonies of the hydroids.

Some of the most beautiful pools of the shore are not exposed to the view of the casual passer‑by. They must be searched for–perhaps in low‑lying basins hidden by great rocks that seem to be heaped in disorder and confusion, perhaps in darkened recesses under a projecting ledge, perhaps behind a thick curtain of concealing weeds.

I know such a hidden pool. It lies in a sea cave, at low tide filling perhaps the lower third of its chamber. As the flooding tide returns the pool grows, swelling in volume until all the cave is water‑filled and the cave and the rocks that form and contain it are drowned beneath the fullness of the tide. When the tide is low, however, the cave may be approached from the landward side. Massive rocks form its floor and walls and roof. They are penetrated by only a few openings–two near the floor on the sea side and one high on the landward wall. Here one may lie on the rocky threshold and peer through the low entrance into the cave and down into its pool. The cave is not really dark; indeed on a bright day it glows with a cool green light. The source of this soft radiance is the sunlight that enters through the openings low on the floor of the pool, but only after its entrance into the pool does the light itself become transformed, invested with a living color of purest, palest green that is borrowed from the covering of sponge on the floor of the cave.

Through the same openings that admit the light, fish come in from the sea, explore the green hall, and depart again into the vaster waters beyond. Through those low portals the tides ebb and flow. Invisibly, they bring in minerals–the raw materials for the living chemistry of the plants and animals of the cave. They bring, invisibly again, the larvae of many sea creatures–drifting, drifting in their search for a resting place. Some may remain and settle here; others will go out on the next tide.

Looking down into the small world confined within the walls of the cave, one feels the rhythms of the greater sea world beyond. The waters of the pool are never still. Their level changes not only gradually with the rise and fall of the tide, but also abruptly with the pulse of the surf. As the backwash of a wave draws it seaward, the water falls away rapidly; then with a sudden reversal the inrushing water foams and surges upward almost to one’s face.

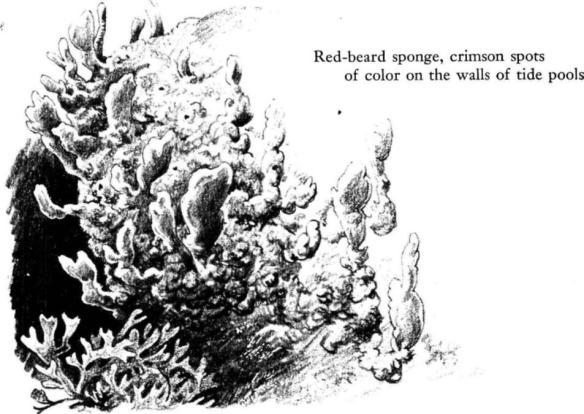

On the outward movement one can look down and see the floor, its details revealed more clearly in the shallowing water. The green crumb‑of‑bread sponge covers much of the bottom of the pool, forming a thick‑piled carpet built of tough little feltlike fibers laced together with glassy, double‑pointed needles of silica–the spicules or skeletal supports of the sponge. The green color of the carpet is the pure color of chlorophyll, this plant pigment being confined within the cells of an alga that are scattered through the tissues of the animal host. The sponge clings closely to the rock, by the very smoothness and flatness of its growth testifying to the streamlining force of heavy surf. In quiet waters the same species sends up many projecting cones; here these would give the turbulent waters a surface to grip and tear.

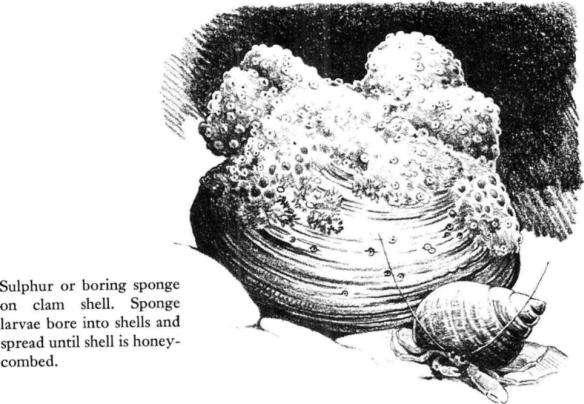

Interrupting the green carpet are patches of other colors, one a deep, mustard yellow, probably a growth of the sulphur sponge. In the fleeting moment when most of the water has drained away, one has glimpses of a rich orchid color in the deepest part of the cave–the color of the encrusting coralline algae.

Sponges and corallines together form a background for the larger tide‑pool animals. In the quiet of ebb tide there is little or no visible movement even among the predatory starfish that cling to the walls like ornamental fixtures painted orange or rose or purple. A group of large anemones lives on the wall of the cave, their apricot color vivid against the green sponge. Today all the anemones may be attached on the north wall of the pool, seemingly immobile and immovable; on the next spring tides when I visit the pool again some of them may have shifted over to the west wall and there taken up their station, again seemingly immovable.

There is abundant promise that the anemone colony is a thriving one and will be maintained. On the walls and ceiling of the cave are scores of baby anemones–little glistening mounds of soft tissue, a pale, translucent brown. But the real nursery of the colony seems to be in a sort of antechamber opening into the central cave. There a roughly cylindrical space no more than a foot across is enclosed by high perpendicular rock walls to which hundreds of baby anemones cling.

On the roof of the cave is written a starkly simple statement of the force of the surf. Waves entering a confined space always concentrate all their tremendous force for a driving, upward leap in this manner the roofs of caves are gradually battered away. The open portal in which I lie saves the ceiling of this cave from receiving the full force of such upward‑leaping waves; nevertheless, the creatures that live there are exclusively a heavy‑surf fauna. It is a simple black and white mosaic–the black of mussel shells, on which the white cones of barnacles are growing. For some reason the barnacles, skilled colonizers of surf‑swept rocks though they be, seem to have been unable to get a foothold directly on the roof of the cave. Yet the mussels have done so. I do not know how this happened but I can guess. I can imagine the young mussels creeping in over the damp rock while the tide is out, spinning their silk threads that bind them securely, anchoring them against the returning waters. And then in time, perhaps, the growing colony of mussels gave the infant barnacles a foothold more tenable than the smooth rock, so that they were able to cement themselves to the mussel shells. However it came about, that is the way we find them now.

As I lie and look into the pool there are moments of relative quiet, in the intervals when one wave has receded and the next has not yet entered. Then I can hear the small sounds: the sound of water dripping from the mussels on the ceiling or of water dripping from seaweeds that line the walls–small, silver splashes losing themselves in the vastness of the pool and in the confused, murmurous whisperings that emanate from the pool itself–the pool that is never quite still.

Then as my fingers explore among the dark red thongs of the dulse and push away the fronds of the Irish moss that cover the walls beneath me, I begin to find creatures of such extreme delicacy that I wonder how they can exist in this cave when the brute force of storm surf is unleashed within its confined space.

Adhering to the rock walls are thin crusts of one of the bryozoans, a form in which hundreds of minute, flask‑shaped cells of a brittle structure, fragile as glass, lie one against another in regular rows to form a continuous crust. The color is a pale apricot; the whole seems an ephemeral creation that would crumble away at a touch, as hoarfrost before the sun.

A tiny spiderlike creature with long and slender legs runs about over the crust. For some reason that may have to do with its food, it is the same apricot color as the bryozoan carpet beneath it; the sea spider, too, seems the embodiment of fragility.

Another bryozoan of coarser, upright growth, Flustrella, sends up little club‑shaped projections from a basal mat. Again, the lime‑impregnated clubs seem brittle and glassy. Over and among them, innumerable little roundworms crawl with serpentine motion, slender as threads. Baby mussels creep in their tentative exploration of a world so new to them they have not yet found a place to anchor themselves by slender silken lines.

Exploring with my lens, I find many very small snails in the fronds of seaweed. One of them has obviously not been long in the world, for its pure white shell has formed only the first turn of the spiral that will turn many times upon itself in growth from infancy to maturity. Another, no larger, is nevertheless older. Its shining amber shell is coiled like a French horn and, as I watch, the tiny creature within thrusts out a bovine head and seems to be regarding its surroundings with two black eyes, small as the smallest pinpoints.

But seemingly most fragile of all are the little calcareous sponges that here and there exist among the seaweeds. They form masses of minute, upthrust tubes of vase‑like form, none more than half an inch high. The wall of each is a mesh of fine threads–a web of starched lace made to fairy scale.

I could have crushed any of these fragile structures between my fingers–yet somehow they find it possible to exist here, amid the surging thunder of the surf that must fill this cave as the sea comes in. Perhaps the seaweeds are the key to the mystery, their resilient fronds a sufficient cushion for all the minute and delicate beings they contain.

But it is the sponges that give to the cave and its pool their special quality–the sense of a continuing flow of time. For each day that I visit the pool on the lowest tides of the summer they seem unchanged–the same in July, the same in August, the same in September. And they are the same this year as last, and presumably as they will be a hundred or a thousand summers hence.

Simple in structure, little different from the first sponges that spread their mats on ancient rocks and drew their food from a primordial sea, the sponges bridge the eons of time. The green sponge that carpets the floor of this cave grew in other pools before this shore was formed; it was old when the first creatures came out of the sea in those ancient eras of the Paleozoic, 300 million years ago; it existed even in the dim past before the first fossil record, for the hard little spicules–all that remains when the living tissue is gone–are found in the first fossil‑bearing rocks, those of the Cambrian period.

So, in the hidden chamber of that pool, time echoes down the long ages to a present that is but a moment.

As I watched, a fish swam in, a shadow in the green light, entering the pool by one of the openings low on its seaward wall. Compared with the ancient sponges, the fish was almost a symbol of modernity, its fishlike ancestry traceable only half as far into the past. And I, in whose eyes the images of the two were beheld as though they were contemporaries, was a mere newcomer whose ancestors had inhabited the earth so briefly that my presence was almost anachronistic.

As I lay at the threshold of the cave thinking those thoughts, the surge of waters rose and flooded across the rock on which I rested. The tide was rising.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 1176;