IV. The Rim of Sand 2 страница

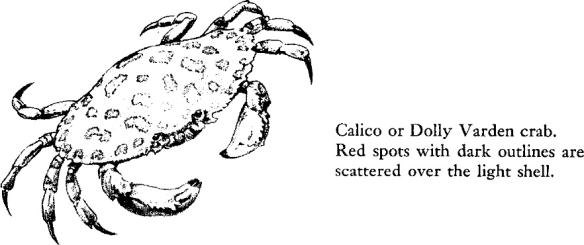

Few of those who build permanent homes in this underground city of sand live by themselves. On the Atlantic coast, the ghost shrimp regularly gives lodging to a small rotund crab, related to the species often found in oysters. The pea crab, Pinnixa, finds in the well‑aerated burrow of the shrimp both shelter and a steady supply of food. It strains food out of the water currents that flow through the burrow, using little feathery outgrowths of its body as nets. On the California coast the ghost shrimp shelters as many as ten different species of animals. One is a fish–a small goby–that uses the burrow as a casual refuge while the tide is out, roaming through the passageways of the shrimp’s home and pushing past the owner when necessary. Another is a clam that lives outside the burrow but thrusts its siphons through the walls and takes food from the water circulating through the tunnel. The clam has short siphons and in ordinary circumstances would have to live just under the surface of the sand to reach water and its food supply; by establishing connection with the shrimp’s burrow it is able to enjoy the protective advantages of living at a deeper level.

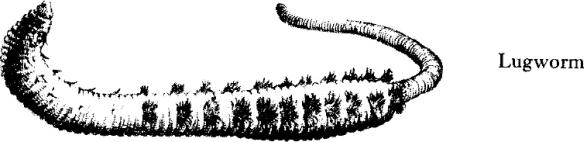

On the muddier parts of these same Georgia flats the lugworm lives, its presence marked by round black domes, like low volcanic cones. Wherever the lugworms occur, on shores of America and Europe, their prodigious toil leavens and renews the beaches and keeps the amount of decaying organic matter in proper balance. Where they are abundant, they may work over in a year nearly two thousand tons of soil per acre. Like its counterpart on land, the earthworm, the lugworm passes quantities of soil through its body. The food in decaying organic debris is absorbed by its digestive tract; the sand is expelled in neat, coiled castings that betray the presence of the worm. Near every dark cone, a small, funnel‑shaped depression appears in the sand. The worm lies within the sand in the shape of the letter U, the tail under the cone, the head under the depression. When the tide rises, the head is thrust out to feed.

Other signs of the lugworm appear in midsummer–large, translucent, pink sacs, each bobbing about in the water like a child’s balloon, with one end drawn down into the sand. These compact masses of jelly are the egg masses of the worm, within each of which as many as 300,000 young are undergoing development.

Vast plains of sand are continually worked over by these and other marine worms. One–the trumpet worm–uses the very sand that contains its food to make a cone‑shaped tube for the protection of its soft body in tunneling. One may sometimes see the living trumpet worm at work, for it allows its tube to project slightly above the surface. It is much more common, however, to find the empty tubes in the tidal debris. Despite their fragile appearance, they remain intact long after their architects are dead–natural mosaics of sand, one grain thick, the building stones fitted together with meticulous care.

A Scot named A. T. Watson once spent many years studying the habits of this worm. Because tube‑building goes on under ground, he found it almost impossibly difficult to observe the fitting into place and cementing of sand grains until he hit upon the idea of collecting very young larvae, which could live and be observed in a thin layer of sand in the bottom of a laboratory dish. The building of the tube was begun soon after the larvae had ceased to swim about and had settled on the bottom of the dish. First each secreted a membranous tube about itself. This was to become the inner lining of the cone, and the foundation for the sand‑grain mosaic. These young larvae had only two tentacles, which they used to collect grains of sand and pass them to the mouth. There the grains were rolled about experimentally, and if found suitable, were deposited on the chosen spot at the edge of the tube. Then a little fluid was expelled from the cement gland, after which the worm rubbed certain shield‑like structures over the tube as though to smooth it.

“Each tube,” wrote Watson, “is the life work of the tenant, and is most beautifully built with grains of sand, each grain placed in position with all the skill and accuracy of a human builder … The moment when an exact fit has been obtained is evidently ascertained by an exquisite sense of touch. On one occasion I saw the worm slightly alter (before cementing) the position of a sand grain which it had just deposited.”

The tubes serve to house the owners during a lifetime of subterranean tunneling, for like the lugworm, this species finds its food in the subsurface sands. The digging organs, like the tubes, belie their fragile appearance. They are slender, sharp‑pointed bristles arranged in two groups, or “combs,” which look fantastically impractical. We could easily believe that someone, in whimsical mood, had cut them out of shining golden foil, fringing the margins with repeated snips of the scissors to fashion a Christmas tree ornament.

I have watched the worms at work, in a miniature world of sand and sea created for them in my laboratory. Even in a thin layer of sand in a glass bowl, the combs are used with a sturdy efficiency that reminds one of a bulldozer. The worm emerges slightly from the tube, thrusts the combs into the sand, scoops up a load and throws it over its shoulder, as it were; than it seems to scrape the shovel blades clean by drawing them back over the edge of the tube. The whole thing is done with vigor and dispatch, with motions alternately to right and left. The golden shovels loosen the sand and allow the soft, food‑gathering tentacles to explore among the grains, and bring to the mouth the food they discover.

Down along the line of barrier islands that stands between the mainland and the sea, the waves have cut inlets through which the tides pour into the bays and sounds behind the islands. The seaward shores of the islands are bathed by coastwise currents carrying their loads of sand and silt, mile after mile. In the confusion of meeting the tides that are racing to or from the inlets, the currents slacken and relax their hold on some of the sediments. So, off the mouths of many of the inlets, lines of shoals make out to sea–the wrecking sands of Diamond Shoal and Frying Pan Shoal and scores of others, named or nameless. But not all of the sediments are so deposited. Many are seized by the tides and swept through the inlets, only to be dropped in the quieter waters inside. Within the capes and the inlet mouths, in the bays and sounds, the shoals build up. Where they exist the searching larvae or young of sea creatures find them–creatures whose way of life requires quiet and shallow water.

Within the shelter of Cape Lookout there are such shoals reaching upward to the surface, emerging briefly into sun and air for the interval of the low tide, then sinking again into the sea. They are seldom crossed by heavy surf, and while the tidal currents that swirl over or around them may gradually alter their shape and extent–today borrowing some of their substance, tomorrow repaying it with sand or silt brought from other areas–they are on the whole a stable and peaceful world for the animals of the sands.

Some of the shoals bear the names of the creatures of air and water that visit them–Shark, Sheepshead, Bird. To visit Bird Shoal, one goes out by boat through channels winding through the Town Marsh of Beaufort and comes ashore on a rim of sand held firm by the deep roots of beach grasses–the landward border of the shoal. The burrows of thousands of fiddler crabs riddle the muddy beach on the side facing the marshes. The crabs shuffle across the flats at the approach of an intruder, and the sound of many small chitinous feet is like the crackling of paper. Crossing the ridge of sand, one looks out over the shoal. If the tide still has an hour or two to fall to its ebb, one sees only a sheet of water shimmering in the sun.

On the beach, as the tide falls, the border of wet sand gradually retreats toward the sea. Offshore, a dull velvet patch takes form on the shining silk of the water, like the back of an immense fish slowly rolling out of the sea, as a long streak of sand begins to rise into view.

On spring tides the peak of this great sprawling shoal rises farther out of the water and is exposed longer; on the neaps, when the tidal pulse is feeble and the water movements sluggish, the shoal remains almost hidden, with a thin sheet of water rippling across it even at the low point of the ebb. But on any low tide of the month, in calm weather, one is able to wade out from the sand‑dune rim over immense areas of the shoal, in water so shallow and so glassy clear that every detail of the bottom lies revealed.

Even on moderate tides I have gone so far out that the dry sand rim seemed far away. Then deep channels began to cut across the outlying parts of the shoal. Approaching them, I could see the bottom sloping down out of crystal clarity into a green that was dull and opaque. The steepness of the slope was accentuated when a little school of minnows flickered across the shallows and down into the darkness in a cascade of silver sparks. Larger fish wandered in from the sea along these narrow passages between the shoals. I knew there were beds of sun ray clams down there on the deeper bottoms, with whelks moving down to prey on them. Crabs swam about or buried themselves to the eyes in the sandy bottoms; then behind each crab two small vortices appeared in the sand, marking the respiratory currents drawn in through the gills.

Where water–even the shallowest of layers–covered the shoal, life came out of hiding. A young horseshoe crab hurried out into deeper water; a small toadfish huddled down in a clump of eelgrass and croaked an audible protest at the foot of a strange visitor in his world, where human beings seldom intrude. A snail with neat black spirals around its shell and a matching black foot and black, tubular siphons–a banded tulip shell–glided rapidly over the bottom, tracing a clear track across the sand.

Here and there the sea grasses had taken hold–those pioneers among the flowering plants that are venturing out into salt water. Their flat leaf blades pushed up through the sand and their interlacing roots lent firmness and stability to the bottom. In such glades I found colonies of a curious, sand‑dwelling sea anemone. Because of their structure and habits, anemones require some firm support to grip while reaching into the water for food. In the north (or wherever there is firm bottom) they grasp the rocks; here they gain the same end by pushing down into the sand until only the crown of tentacles remains above the surface. The sand anemone burrows by contracting the downward‑pointing end of its tube and thrusting downward, then as a slow wave of expansion travels up the body, the creature sinks into the sand. It was strange to see the soft tentacle‑clusters of the anemones flowering here in the midst of the sands, for anemones seem always to belong to the rocks; yet buried in this firm bottom doubtless they were as secure as the great plumose anemone blooming on the wall of a Maine tide pool.

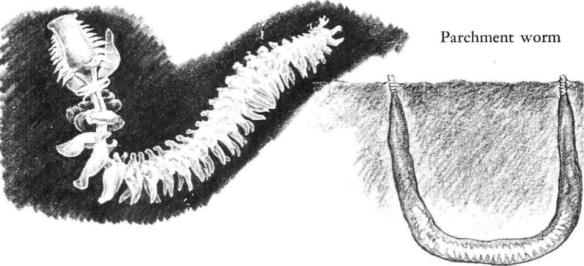

Here and there over the grassy parts of the shoal the twin chimneys of the parchment worm’s tubes protruded slightly above the sand. The worm itself lives always underground, in a U‑shaped tube whose narrowed tips are the animal’s means of contact with the sea. Lying in its tube, it uses fanlike projections of the body to keep a current of water streaming through the dark tunnel of its home, bringing it the minute plant cells that are its principal food, carrying away its waste products and in season the seeds of a new generation.

The whole life of the worm is so spent except for the short period of larval life at sea. The larva soon ceases to swim and, becoming sluggish, settles to the bottom. It begins to creep about, perhaps finding food in the diatoms lying in the troughs of the sand ripples. As it creeps it leaves a trail of mucus. After perhaps a few days the young worm begins to make short, mucus‑coated tunnels, burrowing into thick clumps of diatoms mixed with sand. From such a simple tunnel, extending perhaps several times the length of its body, the larva pushes up extensions to the surface of the sand, to create the U‑shape. All later tunnels are the result of repeated remodelings and extensions of this one, to accommodate the growing body of the worm. After the worm dies the limp, empty tubes are washed out of the sand and are common in the flotsam of the beach.

At some time almost all parchment worms acquire lodgers–the small pea crabs whose relatives inhabit the burrows of the ghost shrimps. Often the association is for life. The crabs, lured by the continuous stream of food‑laden water, enter the worm tube while young, but soon become too large to leave by the narrow exits. Nor does the worm itself actually leave its tube, although occasionally one sees a specimen with a regenerated head or tail–mute evidence that it may emerge enough to tempt a passing fish or crab. Against such attacks it has no defense, unless the weird blue‑white light that illuminates its whole body when disturbed may sometimes alarm an enemy.

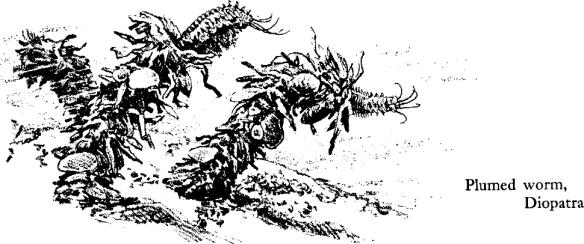

Other little protruding chimneys raised above the surface of the shoal belonged to the plumed or decorator worm, Diopatra. These occurred singly, instead of in pairs. They were curiously adorned with bits of shell or seaweed that effectively deceived the human eye, and were but the exposed ends of tubes that sometimes extended down into the sand as much as three feet. Perhaps the camouflage is effective also against natural enemies, yet to collect the materials that it glues to all exposed parts of its tube, the worm has to expose several inches of its body. Like the parchment worm, it is able to regenerate lost tissues as a defense against hungry fish.

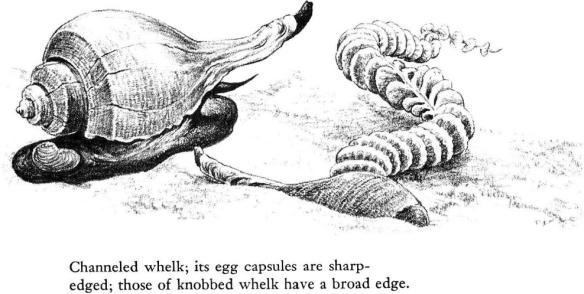

As the tide ebbed away, the great whelks could be seen here and there gliding about in search of their prey, the clams that lay buried in the sands, drawing through their bodies a stream of sea water and filtering from it microscopic plants. Yet the search of the whelks was not an aimless one, for their keen taste sense guided them to invisible streams of water pouring from the outlet siphons of the clams. Such a taste trail might lead to a stout razor clam, whose shells afford only the scantiest covering for its bulging flesh, or to a hard‑shell clam, with tightly closed valves. Even these can be opened by a whelk, which grips the clam in its large foot and, by muscular contractions, delivers a series of hammer blows with its own massive shell.

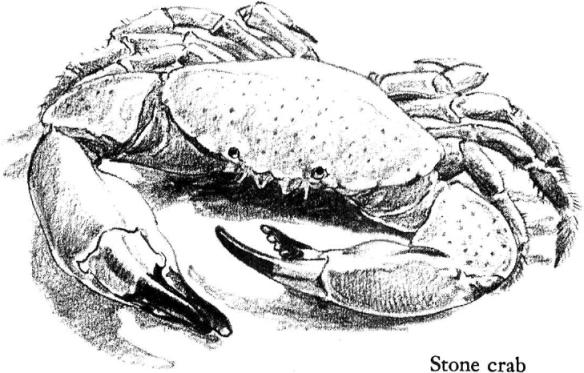

Nor does the cycle of life–the intricate dependence of one species upon another–end there. Down in dark little dens of the sea floor live the enemies of the whelks, the stone crabs of massive purplish bodies and brightly colored crushing claws that are able to break away the whelk’s shell, piece by piece. The crabs lurk in caves among the stones of jetties, in holes eroded out of shell rock, or in man‑made homes such as old, discarded automobile tires. About their lairs, as about the abodes of legendary giants, lie the broken remains of their prey.

If the whelks escape this enemy, another comes by air. The gulls visit the shoal in numbers. They have no great claws to crush the shells of their victims, but some inherited wisdom has taught them another device. Finding an exposed whelk, a gull seizes it and carries it aloft. It seeks a paved road, a pier, or even the beach itself, soars high into the air and drops its prey, instantly following it earthward to recover the treasure from among the shattered bits of shell.

Coming back over the shoal, I saw spiraling up out of the sand, over the edge of a green undersea ravine, a looped and twisted strand–a tough string of parchment on which were threaded many scores of little purse‑shaped capsules. This was the egg string of a female whelk, for it was June, and the spawning time of the species. In all the capsules, I knew, the mysterious forces of creation were at work, making ready thousands of baby whelks, of which perhaps hundreds would survive to emerge from the thin round door in the wall of each capsule, each a tiny being in a miniature shell like that of its parents.

Where the waves roll in from the open Atlantic, with no outlying islands or curving arm of land to break the force of their attack on the beach, the area between the tide lines is a difficult one for living things. It is a world of force and change and constant motion, where even the sand acquires some of the fluidity of water. These exposed beaches have few inhabitants, for only the most specialized creatures can live on sand amid heavy surf.

Animals of open beaches are typically small, always swift‑moving. Theirs is a strange way of life. Each wave breaking on the beach is at once their friend and enemy; though it brings food, it threatens to carry them out to sea in its swirling backwash. Only by becoming amazingly proficient in rapid and constant digging can any animal exploit the turbulent surf and shifting sand for the plentiful food supplies brought in by the waves.

One of the successful exploiters is the mole crab, a surf‑fisher who uses nets so efficient that they catch even microorganisms adrift in the water. Whole cities of mole crabs live where the waves are breaking, following the flood tide shoreward, retreating toward the sea on the ebb. Several times during the rising of a tide, a whole bed of them will shift its position, digging in again farther up the beach in what is probably a more favorable depth for feeding. In this spectacular mass movement, the sand area suddenly seems to bubble, for in a strangely concerted action, like the flocking of birds or the schooling of fish, the crabs all emerge from the sand as a wave sweeps over them. In the rush of turbulent water they are carried up the beach; then, as the wave’s force slackens, they dig into the sand with magical ease, by means of a whirling motion of the tail appendages. With the ebbing of the tide, the crabs return toward the low‑water mark, again making the journey in several stages. If by mischance a few linger until the tide has dropped below them, these crabs dig down several inches into the wet sand and wait for the return of the water.

As the name suggests, there is something mole‑like in these small crustaceans, with their flattened, pawlike appendages. Their eyes are small and practically useless. Like all others who live within the sands the crabs depend less on sight than on the sense of touch, made wonderfully effective by the presence of many sensory bristles. But without the long, curling, feathery antennae, so efficiently constructed that even small bacteria become entangled in their strands, the mole crab could not survive as a fisher of the surf. In preparing to feed, the crab backs down into the wet sand until only the mouth parts and the antennae are exposed. Although it lies facing the ocean, it makes no attempt to take food from the incoming surf. Rather, it waits until a wave has spent its force on the beach and the backwash is draining seaward. When the spent wave has thinned to a depth of an inch or two, the mole crab extends its antennae into the streaming current. After “fishing” for a moment, it draws the antennae through the appendages surrounding its mouth, picking off the captured food. And again in this activity there is a curious display of group behavior, for when one crab thrusts up its antennae, all the others of the colony promptly follow its example.

It is an extraordinary thing to watch the sand come to life if one happens to be wading where there is a large colony of the crabs. One moment it may seem uninhabited. Then, in that fleeting instant when the water of a receding wave flows seaward like a thin stream of liquid glass, there are suddenly hundreds of little gnome‑like faces peering through the sandy floor–beady‑eyed, long‑whiskered faces set in bodies so nearly the color of their background that they can barely be seen. And when, almost instantly, the faces fade back into invisibility, as though a host of strange little troglodytes had momentarily looked out through the curtains of their hidden world and as abruptly retired within it, the illusion is strong that one has seen nothing except in imagination–that there was merely an apparition induced by the magical quality of this world of shifting sand and foaming water.

Since their food‑gathering activities keep them in the edge of the surf, mole crabs are exposed to enemies from both land and water–birds that probe in the wet sand, fish that swim in with the tide, feeding in the rising water, blue crabs darting out of the surf to seize them. So the mole crabs function in the sea’s economy as an important link between the microscopic food of the waters and the large, carnivorous predators.

Even though the individual mole crab may escape the larger creatures that hunt the tide lines, the span of life is short, comprising a summer, a winter, and a summer. The crab begins life as a minute larva hatched from an orange‑colored egg that has been carried for months by the mother crab, one of a mass firmly attached beneath her body. As the time for hatching nears, the mother foregoes the feeding movements up and down the beach with the other crabs and remains near the zone of the low tide, so avoiding the danger of stranding her offspring on the sands of the upper beach.

When it escapes from the protective capsule of the egg, the young larva is transparent, large‑headed, and large‑eyed as are all crustacean young, weirdly adorned with spines. It is a creature of the plankton, knowing nothing of life in the sands. As it grows it molts, shedding the vestments of its larval life. So it reaches a stage in which, although still swimming in larval fashion with waving motions of its bristled legs, it now seeks the bottom in the turbulent surf zone, where the waves stir and loosen the sand. Toward the summer’s end there is another molt, this time bringing transformation to the adult stage, with the feeding behavior of the adult crabs.

During the protracted period of larval life, many of the young mole crabs have made long coastwise journeys in the currents, so that their final coming ashore (if they have survived the voyage) may be far from the parental sands. On the Pacific coast, where strong surface currents flow seaward, Martin Johnson found that great numbers of the crab larvae are carried out over oceanic depths, doomed to certain destruction unless they chance to find their way into a return current. Because of the long larval life, some of the young crabs are carried as far as 200 miles offshore. Perhaps in the prevailing coastwise current of Atlantic shores they travel even farther.

With the coming of winter the mole crabs remain active. In the northern part of their range, where frost bites deep into the sands and ice may form on the beaches, they go out beyond the low‑tide zone to pass the cold months where a fathom or more of insulating water lies between them and the wintry air. Spring is the mating season and by July most or all of the males hatched the preceding summer have died. The females carry their egg masses for several months until the young hatch; before winter all of these females have died and only a single generation of the species remains on the beach.

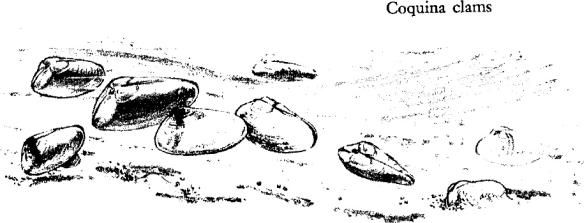

The only other creatures regularly at home between the tide lines of wave‑swept Atlantic beaches are the tiny coquina clams. The life of the coquinas is one of extraordinary and almost ceaseless activity. When washed out by the waves, they must dig in again, using the stout, pointed foot as a spade to thrust down for a firm grip, after which the smooth shell is pulled rapidly into the sand. Once firmly entrenched, the clam pushes up its siphons. The intake siphon is about as long as the shell and flares widely at the mouth. Diatoms and other food materials brought in or stirred from the bottom by waves are drawn down into the siphon.

Like the mole crabs, the coquinas shift higher or lower on the beach in mass movements of scores or hundreds of individuals, perhaps to take advantage of the most favorable depth of water. Then the sand flashes with the brightly colored shells as the clams emerge from their holes and let the waves carry them. Sometimes other small burrowers move with the coquinas among the waves–companies of the little screw shell, Terebra, a carnivorous snail that preys on the coquina. Other enemies are sea birds. The ring‑billed gulls hunt the clams persistently, treading them out of the sand in shallow water.

On any particular beach, the coquinas are transient inhabitants; they seem to work an area for the food it provides, and then move on. The presence on a beach of thousands of the beautifully variegated shells, shaped like butterflies and crossed by radiating bands of color, may mark only the site of a former colony.

Being only briefly and sporadically possessed by the sea in those recurrent periods of the tides’ farthest advance, the high‑tide zone on any shore has in its own nature something of the land as well as of the sea. This intermediate, transitional quality pervades not only the physical world of the upper beach but also its life. Perhaps the ebb and flow of the tides has accustomed some of the intertidal animals, little by little, to living out of water; perhaps this is the reason there are among the inhabitants of this zone some who, at this moment of their history, belong neither to the land nor entirely to the sea.

The ghost crab, pale as the dry sand of the upper beaches it inhabits, seems almost a land animal. Often its deep holes are back where the dunes begin to rise from the beach. Yet it is not an air‑breather; it carries with it a bit of the sea in the branchial chamber surrounding its gills, and at intervals must visit the sea to replenish the water. And there is another, almost symbolic return. Each of these crabs began its individual life as a tiny creature of the plankton; after maturity and in the spawning season, each female enters the sea again to liberate her young.

If it were not for these necessities, the lives of the adult crabs would be almost those of true land animals. But at intervals during each day they must go down to the water line to wet their gills, accomplishing their purpose with the least possible contact with the sea. Instead of wading directly into the water, they take up a position a little above the place where, at the moment, most of the waves are breaking on the beach. They stand sideways to the water, gripping the sand with the legs on the landward side. Human bathers know that in any surf an occasional wave will tower higher than the others and run farther up the beach. The crabs wait, as if they also know this, and after such a wave has washed over them, they return to the upper beach.

They are not always wary of contact with the sea. I have a mental picture of one sitting astride a sea‑oats stem on a Virginia beach, one stormy October day, busily putting into its mouth food particles that it seemed to be picking off the stem. It munched away, intent on its pleasant occupation, ignoring the great, roaring ocean at its back. Suddenly the foam and froth of a breaking wave rolled over it, hurling the crab from the stem and sending both slithering up the wet beach. And almost any ghost crab, hard pressed by a person trying to catch it, will dash into the surf as though choosing a lesser evil. At such times they do not swim, but walk along on the bottom until their alarm has subsided and they venture out again.

Although on cloudy days and even occasionally in full sunshine the crabs may be abroad in small numbers, they are predominantly hunters of the night beaches. Drawing from the cloak of darkness a courage they lack by day, they swarm boldly over the sand. Sometimes they dig little temporary pits close to the water line, in which they lie watching for what the sea may bring them.

The individual crab in its brief life epitomizes the protracted racial drama, the evolutionary coming‑to‑land of a sea creature. The larva, like that of the mole crab, is oceanic, becoming a creature of the plankton once it has hatched from the egg that has been incubated and aerated by the mother. As the infant crab drifts in the currents it sheds its cuticle several times to accommodate the increasing size of its body; at each molt it undergoes slight changes of form. Finally the last larval stage, called the megalops, is reached. This is the form in which all the destiny of the race is symbolized, for it–a tiny creature alone in the sea–must obey whatever instinct drives it shoreward, and must make a successful landing on the beach. The long processes of evolution have fitted it to cope with its fate. Its structure is extraordinary when compared with like stages of closely related crabs. Jocelyn Crane, studying these larvae in various species of ghost crabs, found that the cuticle is always thick and heavy, the body rounded. The appendages are grooved and sculptured so that they may be folded down tightly against the body, each fitting precisely against the adjacent ones. In the hazardous act of coming ashore, these structural adaptations protect the young crab against the battering of the surf and the scraping of sand.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 1282;