IV. The Rim of Sand 3 страница

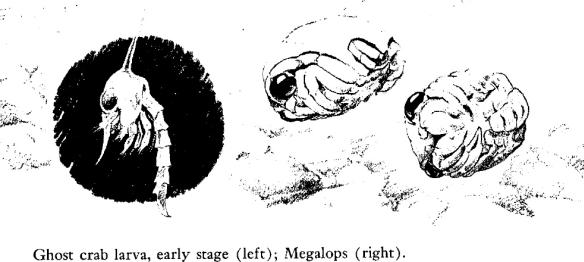

Once on the beach, the larva digs a small hole, perhaps as protection from the waves, perhaps as a shelter in which to undergo the molt that will transform it into the shape of the adult. From then on, the life of the young crab is a gradual moving up the beach. When small it digs its burrows in wet sand that will be covered by the rising tide. When perhaps half grown, it digs above the high‑tide line; when fully adult it goes well back into the upper beach or even among the dunes, attaining then the farthest point of the landward movement of the race.

On any beach inhabited by ghost crabs, their burrows appear and disappear in a daily and seasonal rhythm related to the habits of the owners. During the night the mouths of the burrows stand open while the crabs are out foraging on the beach. About dawn the crabs return. Whether each goes, as a rule, to the burrow it formerly occupied or merely to any convenient one is uncertain–the habit may vary with locality, the age of the crab, and other changing conditions.

Most of the tunnels are simple shafts running down into the sand at an angle of about forty‑five degrees, ending in an enlarged den. Some few have an accessory shaft leading up from the chamber to the surface. This provides an emergency exit to be used if an enemy–perhaps a larger and hostile crab‑comes down the main shaft. This second shaft usually runs to the surface almost vertically. It is farther away from the water than the main tunnel, and may or may not break through the surface of the sand.

The early morning hours are spent repairing, enlarging, or improving the burrow selected for the day. A crab hauling up sand from its tunnel always emerges sideways, its load of sand carried like a package under the legs of the functional rear end of the body. Sometimes, immediately on reaching the burrow mouth, it will hurl the sand violently away and flash back into the hole; sometimes it will carry it a little distance away before depositing it. Often the crabs stock their burrows with food and then retire into them; nearly all crabs close the tunnel entrances about midday.

All through the summer the occurrence of holes on the beach follows this diurnal pattern. By autumn most of the crabs have moved up to the dry beach beyond the tide; their holes reach deeper into the sand as though their owners were feeling the chill of October. Then, apparently, the doors of sand are pulled shut, not to be opened again until spring. For the winter beaches show no sign either of the crabs or of their holes–from dime‑sized youngsters to full‑grown adults, all have disappeared, presumably into the long sleep of hibernation. But, walking the beach on a sunny day in April, one will see here and there an open burrow. And presently a ghost crab in an obviously new and shiny spring coat may appear at its door and very tentatively lean on its elbows in the spring sunshine. If there is a lingering chill in the air, it will soon retire and close its door. But the season has turned, and under all this expanse of upper beach, crabs are awakening from their sleep.

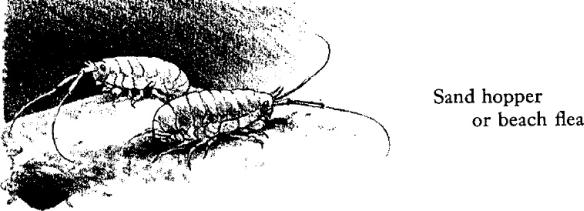

Like the ghost crab, the small amphipod known as the sand hopper or beach flea portrays one of those dramatic moments of evolution, in which a creature abandons an old way of life for a new. Its ancestors were completely marine; its remote descendants, if we read its future aright, will be terrestrial. Now it is midway in the transition from a sea life to a land life.

As in all such transitional existences, there are strange little contradictions and ironies in its way of life. The sand hopper has progressed as far as the upper beach; its predicament is that it is bound to the sea, yet menaced by the very element that gave it life. Apparently it never enters the water voluntarily. It is a poor swimmer and may drown if long submerged. Yet it requires dampness and probably needs the salt in the beach sand, and so it remains in bondage to the water world.

The movements of the sand hoppers follow the rhythm of the tides and the alternation of day and night. On the low tides that fall during the dark hours, they roam far into the intertidal zone in search of food. They gnaw at bits of sea lettuce or eelgrass or kelp, their small bodies swaying with the vigor of their chewing. In the litter of the tide lines they find morsels of dead fish or crab shells containing remnants of flesh; so the beach is cleaned and the phosphates, nitrates, and other mineral substances are recovered from the dead for use by the living.

If low water has fallen late in the night, the amphipods continue their foraging until shortly before daybreak. Before light has tinged the sky, however, all of the hoppers begin to move up the beach toward the high‑water line. There each begins to dig the burrow into which it will retreat from daylight and rising water. As it works rapidly, it passes back the grains of sand from one pair of feet to the next until, with the third pair of thoracic legs, it piles the sand behind it. Now and then the small digger straightens out its body with a snap, so that the accumulated sand is thrown out of the hole. It works furiously at one wall of the tunnel, bracing itself with the fourth and fifth pairs of legs, then turns and begins work on the opposite wall. The creature is small and its legs are seemingly fragile, yet the tunnel may be completed within perhaps ten minutes, and a chamber hollowed out at the end of the shaft. At its maximum depth this shaft represents as prodigious a labor as though a man, working with no tools but his hands, had dug for himself a tunnel about 60 feet deep.

The work of excavation done, the sand flea often returns to the mouth of its burrow to test the security of the entrance door, formed by the accumulation of sand from the deeper parts of the shaft. It may thrust out its long antennae from the mouth of the burrow, feeling the sand, tugging at the grains to draw more of them into the hole. Then it curls up within the dark snug chamber.

As the tide rises overhead, the vibrations of breaking waves and shoreward‑pressing tides may come down to the little creature in its burrow, bringing a warning that it must stay within to avoid water and the dangers brought by water. It is less easy to understand what arouses the protective instinct to avoid daylight, with all the dangers of foraging shore birds. There can be little difference between day and night in that deep burrow. Yet in some mysterious way the beach flea is held within the safety of the sandy chamber until the two essential conditions again prevail on the beach–darkness and a falling tide. Then it awakens from sleep, creeps up the long shaft, and pushes away the sand door. Once again the dark beach stretches before it, and a retreating line of white froth at the edge of the tide marks the boundary of its hunting grounds.

Each den that is dug with so much labor is merely a shelter for one night, or one tidal interval. After the low‑tide feeding period, each hopper will dig itself a new refuge. The holes that we see on the upper beach lead down to empty burrows from which the former occupants have gone. An occupied burrow has its “door” closed, and so its location cannot easily be detected. On the sandy edge of the sea there is, then, the abundant life of protected beaches and shoals, the sparse life of surf‑swept sands, and the pioneering life that has reached the high‑tide line and seems poised in space and time for invasion of the land.

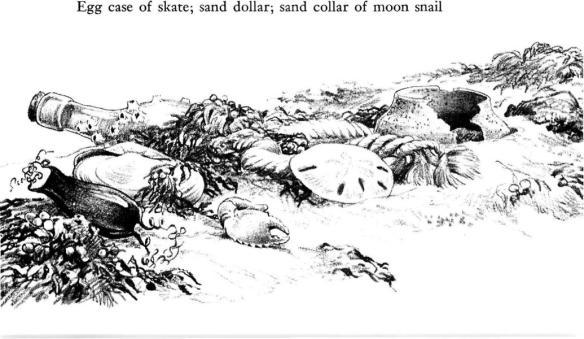

But the sands contain also the record of other lives. A thin net of flotsam is spread over the beaches–the driftage of ocean brought to rest on the shore. It is a fabric of strange composition, woven with tireless energy by wind and wave and tide. The supply of materials is endless. Caught in the strands of dried beach grass and seaweeds there are crab claws and bits of sponge, scarred and broken mollusk shells, old spars crusted with sea growths, the bones of fishes, the feathers of birds. The weavers use the materials at hand, and the design of the net changes from north to south. It reflects the kind of bottom offshore–whether rolling sand hills or rocky reefs; it subtly hints of the nearness of a warm, tropical current, or tells of the intrusion of cold water from the north. In the litter and debris of the beach there may be few living creatures, but there is the suggestion, the intimation of a million, million lives, lived in the sands nearby or brought to this place from far sea distances.

In the beach flotsam there are often strays from the surface waters of the open ocean, reminders of the fact that most sea creatures are the prisoners of the particular water masses they inhabit. When tongues of their native waters, driven by winds or drawn by varying temperature or salinity patterns, stray into unaccustomed territory, this drifting life is carried involuntarily with them.

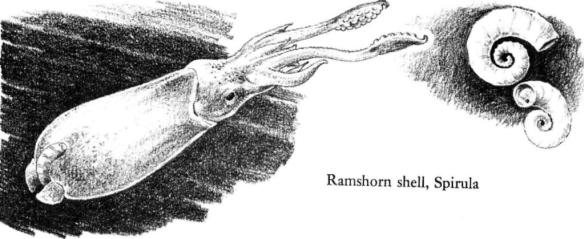

In the several centuries that men of inquiring mind have been walking the world’s shores many unknown sea animals have been discovered as strays from the open ocean in the flotsam of the tide lines. One such mysterious link between the open sea and the shore is the ramshorn shell, Spirula. For many years only the shell had been known–a small white spiral forming two or three loose coils. By holding such a shell to the light, one can see that it is divided into separate chambers, but seldom is there a trace of the animal that built and inhabited it. By 1912, about a dozen living specimens had been found, but still no one knew in what part of the sea the creature lived. Then Johannes Schmidt undertook his classic researches into the life history of the eel, crossing and recrossing the Atlantic and towing plankton nets at different levels from the surface down into depths perpetually black. Along with the glass‑clear larvae of the eels that were the object of his search, he brought up other animals–among them many specimens of Spirula, which had been caught swimming at various depths down to a mile. In their zone of greatest abundance, which seems to lie between 900 and 1500 feet, they probably occur in dense schools. They are little squidlike animals with ten arms and a cylindrical body, bearing fins like propellers at one end. Placed in an aquarium, they are seen to swim with jerky, backward spurts of jet‑propelled motion.

It may seem mysterious that the remains of such a deep‑sea animal should come to rest in beach deposits, but the reason is, after all, not obscure. The shell is extremely light; when the animal dies and begins to decay, the gases of decomposition probably lift it toward the surface. There the fragile shell begins a slow drift in the currents, becoming a natural “drift bottle” whose eventual resting place is a clue not so much to the distribution of the species as to the course of the currents that bore it. The animals themselves live over deep oceans, perhaps most abundantly above the steep slopes that descend from the edges of the continents into the abyss. In such depths, they seem to occupy tropical and subtropical belts around the world. Now, in this little shell curved like the horn of a ram, we have one of the few persisting reminders of the days when great, spiral‑shelled “cuttle fish” swarmed in the oceans of the Jurassic and earlier periods. All other cephalopods, except the pearly or chambered nautilus of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, have either abandoned their shells or converted them to internal remnants.

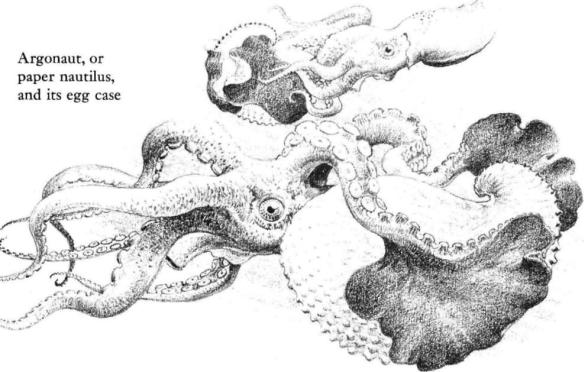

And sometimes, among the tidal debris, there appears a thin papery shell, bearing on its white surface a ribbed pattern like that which shore currents impress upon the sand. It is the shell of the paper nautilus or argonaut, an animal distantly related to an octopus, and like it having eight arms. The argonaut lives on the high seas, in both Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The “shell” is actually an elaborate egg case or cradle secreted by the female for the protection of her young. It is a separate structure that she can enter or leave at will. The much smaller male (about one tenth the size of his mate) secretes no shell. He inseminates the female in the strange manner of some other cephalopods: one of his arms breaks off and enters the mantle cavity of the female, carrying a load of spermatophores. For a long while the male of this creature went unrecognized. Cuvier, a French zoologist of the early nineteenth century, was familiar with the detached arm but supposed it to be an independent animal, probably a parasitic worm. The argonaut is not the chambered or pearly nautilus of Holmes’s famous poem. Although also a cephalopod, the pearly nautilus belongs to a different group and bears a true shell secreted by the mantle. It inhabits tropical seas, and like Spirula is a descendant of the great spiral‑shelled mollusks that dominated the seas of Mesozoic times.

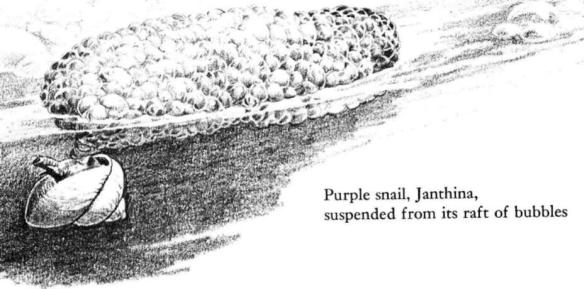

Storms bring in many strays from tropical waters. In a shell shop at Nags Head, North Carolina, I once attempted to buy the beautiful violet snail, Janthina. The proprietor of the shop refused to sell this, her only specimen. I understood why when she told me of finding the living Janthina on the beach after a hurricane, its marvelous float still intact, and the surrounding sand stained purple as the little animal tried, in its extremity, to use its only defense against disaster. Later I found an empty shell, light as thistledown, resting in a depression in the coral rock of Key Largo, where some gentle tide had laid it. I have never been so fortunate as my acquaintance at Nags Head, for I have never seen the living animal.

Janthina is a pelagic snail that drifts on the surface of the open ocean, hanging suspended from a raft of frothy bubbles. The raft is formed from mucus that the animal secretes; the mucus entraps bubbles of air, then hardens into a firm, clear substance like stiff cellophane. In the breeding season the snail fastens its egg capsules to the under side of the raft, which throughout the year serves to keep the little animal afloat.

Like most snails, Janthina is carnivorous; its prey is found among other plankton animals, including small jellyfishes, crustaceans, and even small goose barnacles. Now and then a swooping gull drops from the sky and takes a snail–but for the most part the bubble raft must be excellent camouflage, almost indistinguishable from a bit of drifting sea froth. There must be other enemies that come from below, for the blue‑to‑violet tints of the shell (which hangs below the raft) are the colors worn by many creatures that live at or near the surface film and need to conceal themselves from enemies looking up from below.

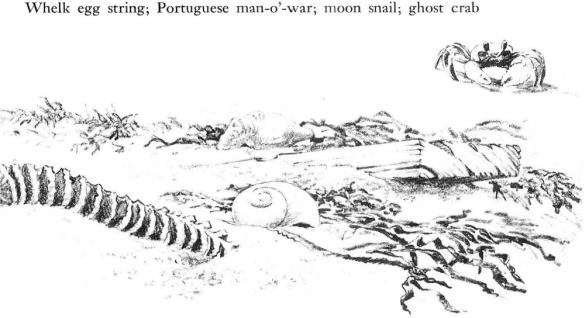

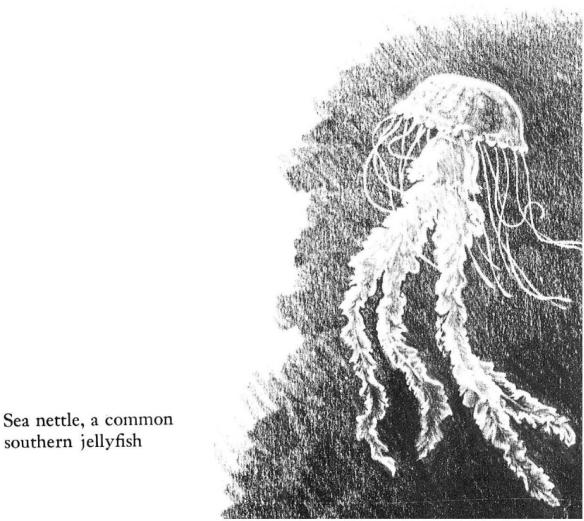

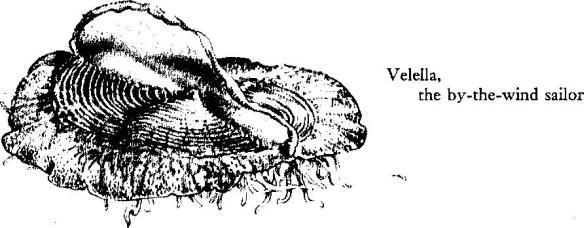

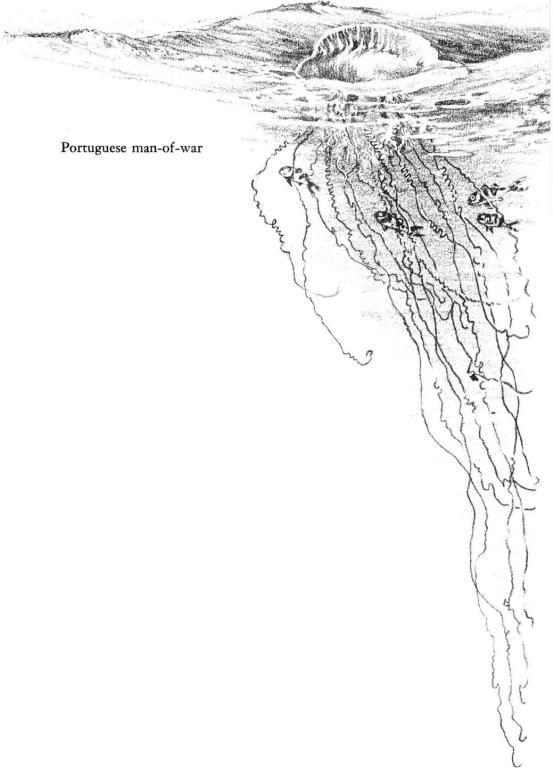

The strong northward flow of the Gulf Stream bears on its surface fleets of living sails–those strange coelenterates of the open sea, the siphonophores. Because of adverse winds and currents these small craft sometimes come into shallow water and are stranded on the beaches. This happens most often in the south, but the southern coast of New England also receives strays from the Gulf Stream, for the shallows west of Nantucket act as a trap to collect them. Among such strays, the beautiful azure sail of the Portuguese man‑of‑war, Physalia, is known to almost everyone, for so conspicuous an object can hardly be missed by any beach walker. The little purple sail, or by‑the‑wind sailor, Velella, is known to fewer, perhaps because of its much smaller size and the fact that once left on the beach it dries quickly to an object that is hard to identify. Both are typically inhabitants of tropical waters, but in the warmth of the Gulf Stream they may sometimes go all the way across to the coast of Great Britain, where in certain years they appear in numbers.

In life the oval float of Velella is a beautiful blue color, with a little elevated crest or sail passing diagonally across it. The disc is about an inch and a half long and half as wide. This is not one animal but a composite one, or colony of inseparably associated individuals–the multiple offspring of a single fertilized egg. The various individuals carry on separate functions. A feeding individual hangs suspended from the center of the float. Small reproductive individuals cluster around it. Around the periphery of the float, feeding individuals in the form of long tentacles hang down to capture the small fry of the sea.

A whole fleet of Portuguese men‑of‑war is sometimes seen from vessels crossing the Gulf Stream when some peculiarity of the wind and current pattern has brought together a number of them. Then one can sail for hours or days with always some of the siphonophores in sight. With, the float or sail set diagonally across its base, the creature sails before the wind; looking down into the clear water one can see the tentacles trailing far below the float. The Portuguese man‑of‑war is like a small fishing boat trailing a drift net, but its “net” is more nearly like a group of high‑voltage wires, so deadly is the sting of the tentacles to almost any fish or other small animal unlucky enough to encounter them.

The true nature of the man‑of‑war is difficult to grasp, and indeed many aspects of its biology are unknown. But, as with Velella, the central fact is that what appears to be one animal is really a colony of many different individuals, although no one of them could exist independently. The float and its base are thought to be one individual; each of the long trailing tentacles another. The food‑capturing tentacles, which in a large specimen may extend down for 40 or 50 feet, are thickly studded with nematocysts or stinging cells. Because of the toxin injected by these cells, Physalia is the most dangerous of all the coelenterates.

For the human bather, even glancing contact with one of the tentacles produces a fiery welt; anyone heavily stung is fortunate to survive. The exact nature of the poison is unknown. Some people believe there are three toxins involved, one producing paralysis of the nervous system, another affecting respiration, the third resulting in extreme prostration and death, if a large dose is received: In areas where Physalia is abundant, bathers have learned to respect it. On some parts of the Florida coast the Gulf Stream passes so close inshore that many of these coelenterates are borne in toward the beaches by onshore winds. The Coast Guard at Lauderdale‑by‑the‑Sea and other such places, when posting reports of tides and water temperatures, often includes forecasts of the relative number of Physalias to be expected inshore.

Because of the highly toxic nature of the nematocyst poisons, it is extraordinary to find a creature that apparently is unharmed by them. This is the small fish Nomeus, which lives always in the shadow of a Physalia. It has never been found in any other situation. It darts in and out among the tentacles with seeming impunity, presumably finding among them a refuge from enemies. In return, it probably lures other fish within range of the man‑of‑war. But what of its own safety? Is it actually immune to the poisons? Or does it live an incredibly hazardous life? A Japanese investigator reported years ago that Nomeus actually nibbles away bits of the stinging tentacles, perhaps in this way subjecting itself to minute doses of the poison throughout its life and so acquiring immunity. But some recent workers contend that the fish has no immunity whatever, and that every live Nomeus is simply a very lucky fish.

The sail, or float, of a Portuguese man‑of‑war is filled with gas secreted by the so‑called gas gland. The gas is largely nitrogen (85 to 91 per cent) with a small amount of oxygen and a trace of argon. Although some siphonophores can deflate the air sac and sink into deep water if the surface is rough, Physalia apparently cannot. However, it does have some control over the position and degree of expansion of the sac. I once had a graphic demonstration of this when I found a medium‑size man‑of‑war stranded on a South Carolina beach. After keeping it overnight in a bucket of salt water, I attempted to return it to the sea. The tide was ebbing; I waded out into the chilly March water, keeping the Physalia in its bucket out of respect for its stinging abilities, then hurled it as far into the sea as I could. Over and over, the incoming waves caught it and returned it to the shallows. Sometimes with my help, sometimes without, it would manage to take off again, visibly adjusting the shape and position of the sail as it scudded along before the wind, which was blowing out of the south, straight up the beach. Sometimes it could successfully ride over an incoming wave; sometimes it would be caught and hustled and bumped along through thinning waters. But whether in difficulty or enjoying momentary success, there was nothing passive in the attitude of the creature. There was, instead, a strong illusion of sentience. This was no helpless bit of flotsam, but a living creature exerting every means at its disposal to control its fate. When I last saw it, a small blue sail far up the beach, it was pointed out to sea, waiting for the moment it could take off again.

Although some of the derelicts of the beach reflect the pattern of the surface waters, others reveal with equal clarity the nature of the sea bottom offshore. For thousands of miles from southern New England to the tip of Florida the continent has a continuous rim of sand, extending in width from the dry sand hills above the beaches far out across the drowned lands of the continental shelf. Yet here and there within this world of sand there are hidden rocky areas. One of these is a scattered and broken chain of reefs and ledges, submerged beneath the green waters off the Carolinas, sometimes close inshore, sometimes far out on the western edge of the Gulf Stream. Fishermen call them “black rocks” because the blackfish congregate around them. The charts refer to “coral” although the closest reef‑building corals are hundreds of miles away, in southern Florida.

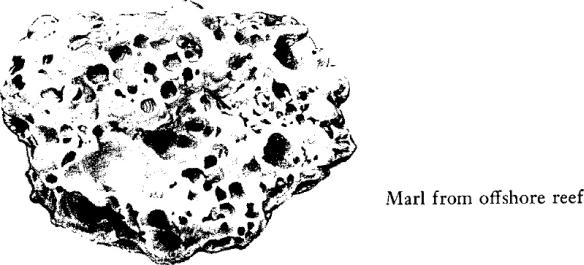

In the 1940’s, biologist divers from Duke University explored some of these reefs and found that they are not coral, but an outcropping of a soft claylike rock known as marl. It was formed during the Miocene many thousands of years ago, then buried under layers of sediment and drowned by a rising sea. As the divers described them, these submerged reefs are low‑lying masses of rock sometimes rising a few feet above the sand, sometimes eroded away to level platforms from which swaying forests of brown sargassum grow. In deep fissures other algae find places of attachment. Much of the rock is smothered under curious sea growths, plant and animal. The stony coralline algae, whose relatives paint the low‑tide rocks of New England a deep, old‑rose hue, encrust the higher parts of the open reef and fill its interstices. Much of the reef is covered by a thick veneer of twisting, winding, limy tubes–the work of living snails and of tube‑building worms, forming a calcareous layer over the old, fossil rock. Through the years the accumulation of algae and the growth of snail and worm tubes have added, little by little, to the structure of the reef.

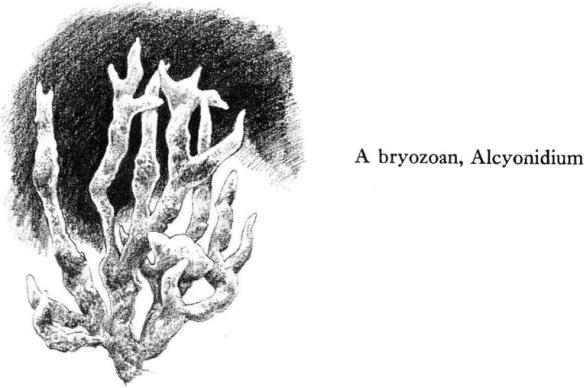

Where the reef rock is free from crusts of algae and worm tubes, boring mollusks–date mussels, piddocks, and small boring clams–have drilled into it, scraping out holes in which they lodge, while feeding on the minute life of the water. Because of the firm support provided by the reef, gardens of color bloom in the midst of the drabness of shifting sand and silt. Sponges, orange or red or ocher, extend their branches into the currents that drift across the reef. Fragile, delicately branching hydroids rise from the rocks and from their pale “flowers,” in season, tiny jellyfish swim away. Gorgonians are like tall wiry grasses, orange and yellow. And a curious shrubby form of moss animal or bryozoan lives here, the tough and gelatinous structure of its branches containing thousands of tiny polyps, which thrust out tentacled heads to feed. Often this bryozoan grows around a gorgonian, then appearing like gray insulation around a dark, wiry core.

Were it not for the reefs, none of these forms could exist on this sandy coast. But because, through the changing circumstances of geologic history, the old Miocene rocks are now cropping out on this shallow sea floor, there are places where the planktonic larvae of such animals, drifting in the currents, may end their eternal quest for solidity.

After almost any storm, at such places as South Carolina’s Myrtle Beach, the creatures from the reefs begin to appear on the intertidal sands. Their presence is the visible result of a deep turbulence in the offshore waters, with waves reaching down to sweep violently over those old rocks that have not known the crash of surf since the sea drowned them, thousands of years ago. The storm waves dislodge many of the fixed and sessile animals and sweep off some of the free‑living forms, carrying them away into an alien world of sandy bottoms, of waters shallowing ever more and more until there is no more water beneath them, only the sands of the beach.

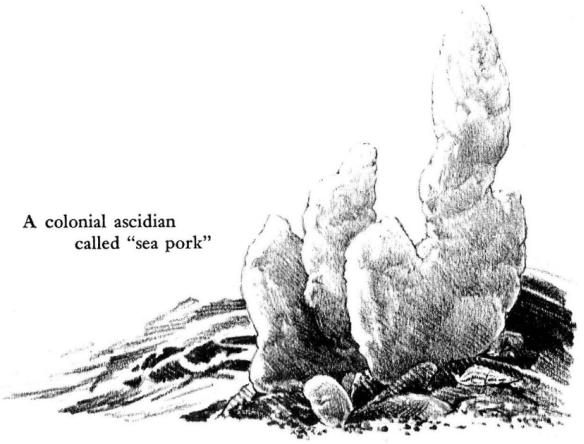

I have walked these beaches in the biting wind that lingers after a northeast storm, with the waves jagged on the horizon and the ocean a cold leaden hue, and have been stirred by the sight of masses of the bright orange tree sponge lying on the beach, by smaller pieces of other sponges, green and red and yellow, by glistening chunks of “sea pork” of translucent orange or red or grayish white, by sea squirts like knobby old potatoes, and by living pearl oysters still gripping the thin branches of gorgonians. Sometimes there have been living starfish–the dark red southern form of the rock‑dwelling Asterias. Once there was an octopus in distress on the wet sands where the waves had thrown it. But life was still in it; when I helped it out beyond the breakers it darted away.

Pieces of the ancient reef itself are commonly found on the sand at Myrtle Beach and presumably at any place where such reefs lie offshore. The marl is a dull gray cement‑like rock, full of the borings of mollusks and sometimes retaining their shells. The total number of borers is always so great that one thinks how intense must be the competition, down on that undersea rock platform, for every available inch of solid surface, and how many larvae must fail to find a footing.

Another kind of “rock” occurs on the beach in chunks of varied size and perhaps even more abundantly than the marl. It has almost the structure of honeycomb taffy, being completely riddled with little twisting passageways. The first time one sees this on the beach, especially if it is half buried in sand, one might almost take it for one of the sponges, until investigation proves it to be hard as rock. It is not of mineral origin, however–it is built by small sea worms, dark of body and tentacled of head. These worms, living in aggregations of many individuals, secrete about themselves a calcareous matrix, which hardens to the firmness of rock. Presumably it thickly encrusts the reefs or builds up solid masses from a rocky floor. This particular kind of “worm rock” had not been known from the Atlantic coast until Dr. Olga Hartman identified my specimens from Myrtle Beach as “a matrix‑building species of Dodecaceria” whose closest relatives are Pacific and Indian Ocean inhabitants. How and when did this particular species reach the Atlantic? How extensive is its range there? These and many other questions remain to be answered; they are one small illustration of the fact that our knowledge is encompassed within restricted boundaries, whose windows look out upon the limitless spaces of the unknown.

On the upper beach, beyond the zone where the flood tide returns the sea water twice daily, the sands dry out. Then they are subjected to excesses of heat; their arid depths are barren, with little to attract life, or even to make life possible. The grains of dry sands rub one against another. The winds seize them and drive them in a thin mist above the beach, and the cutting edge of this wind‑driven sand scours the driftwood to a silver sheen, polishes the trunks of old derelict trees, and scourges the birds that nest on the beach.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 1268;