III. The Rocky Shores 4 страница

After the union of the male and female nuclei, the division of the fertilized cell proceeds rapidly. In less than the interval between a high and a low tide, the egg has been transformed into a little ball of cells, propelling itself through the water with glittering hairs, or cilia. In about twenty‑four hours, it has assumed an odd, top‑shaped form that is common to the larvae of all young mollusks and annelid worms. A few days more and it has become flattened and elongated and swims rapidly by vibrations of a membrane called the velum; it crawls over solid surfaces, and senses contact with foreign objects. Its journey through the sea is far from being a solitary one; in a square meter of surface over a bed of adult mussels there may be as many as 170,000 swimming larvae.

The thin larval shell takes form, but soon it is replaced by another, double‑valved as in adult mussels. By this time the velum has disintegrated, and the mantle, foot, and other organs of the adult have begun their development.

From early summer these tiny shelled creatures live in prodigious numbers in the seaweeds of the shore. In almost every bit of weed I pick up for microscopic examination I find them creeping about, exploring their world with the long tubular organ called the foot, which bears an odd resemblance to the trunk of an elephant. The infant mussel uses it to test out objects in its path, to creep over level or steeply sloping rocks or through seaweeds, or even to walk on the under side of the surface film of quiet water. Soon, however, the foot assumes a new function: it aids in the work of spinning the tough silken threads that anchor a mussel to whatever offers a solid support and insurance against being washed away in the surf.

The very existence of the mussel fields of the low‑tide zone is evidence that this chain of circumstances has proceeded unbroken to its consummation untold millions upon millions of times. Yet, for every mussel surviving upon the rocks, there must have been millions of larvae whose setting forth into the sea had a disastrous end. The system is in delicate balance; barring catastrophe, the forces that destroy neither outweigh nor are outweighed by those that create, and over the years of a man’s life, as over the ages of recent geologic time, the total number of mussels on the shore probably has remained about the same.

In much of this low‑water area the mussels live in intimate association with one of the red seaweeds, Gigartina, a plant of low‑growing, bushy form and almost cartilaginous texture. Plants and mussels unite inseparably to form a tough mat. Very small mussels may grow about the plants so abundantly as to obscure their basal attachment to the rocks. Both the stems and the repeatedly subdivided branches of the seaweed are astir with life, but with life on so small a scale that the human eye can see its details only with the aid of a microscope.

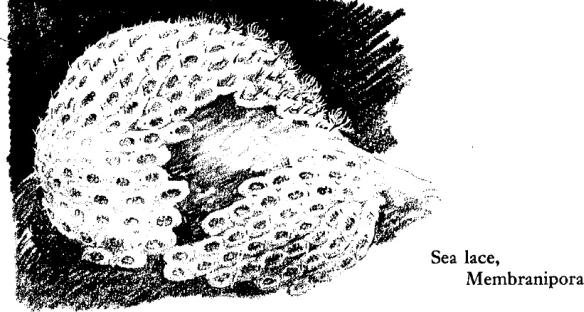

Snails, some with brightly banded and deeply sculptured shells, crawl along the fronds, browsing on microscopic vegetable matter. Many of the basal stems of the weed are thickly encrusted with the bryozoan sea lace, Membranipora; from all its compartments the minute, be‑tentacled heads of the resident creatures are thrust out. Another bryozoan of coarser growth, Flustrella, also forms mats investing the broken stems and stubble of the red weed, the substance of its own growth giving such a stem almost the thickness of a pencil. Rough hairs or bristles protrude from the mat, so that much foreign matter adheres to it. Like the sea laces, however, it is formed of hundreds of small, adjacent compartments. From one after another of these, as I watch through my microscope, a stout little creature cautiously emerges, then unfurls its crown of filmy tentacles as one would open an umbrella. Threadlike worms creep over the bryozoan, winding among the bristles like snakes through coarse stubble. A tiny, cyclopean crustacean, with one glittering ruby eye, runs ceaselessly and rather clumsily over the colony, apparently disturbing the inhabitants, for when one of them feels the touch of the blundering crustacean it quickly folds its tentacles and withdraws into its compartment.

In the upper branches of this jungle formed by the red weed, there are many nests or tubes occupied by amphipod crustaceans known as Amphithoe. These small creatures have the appearance of wearing cream‑colored jerseys brightly splotched with brownish red; in each goatlike face are set two conspicuous eyes and two pairs of hornlike antennae. The nests are as firmly and skillfully constructed as a bird’s but are subject to far more continuous use, for these amphipods are weak swimmers and ordinarily seem loath to leave their nests. They lie in their snug little sacs, often with the heads and upper parts of their bodies protruding. The water currents that pass through their seaweed home bring them small plant fragments and thus solve the problem of subsistence.

For most of the year Amphithoe lives singly, one to a nest. Early in the summer the males visit the females (who greatly outnumber them) and mating occurs within the nest. As the young develop the mother cares for them in a brood‑pouch formed by the appendages of her abdomen. Often, while carrying her young, she emerges almost completely from her nest and vigorously fans currents of water through the pouch.

The eggs yield embryos, the embryos become larvae; but still the mother holds and cares for them until their small bodies have so developed that they are able to set forth into the seaweeds, to spin their own nests out of the fibers of plants and the silken threads mysteriously fashioned in their own bodies, and to feed and fend for themselves.

As her young become ready for independent life, the mother shows impatience to be rid of the swarm in her nest. Using claws and antennae, she pushes them to the rim and with shoves and nudges tries to expel them. The young cling with hooked and bristled claws to the walls and doorway of the familiar nursery. When finally thrust out they are likely to linger nearby; when the mother incautiously emerges, they leap to attach themselves to her body and so be drawn again into the security of their accustomed nest, until maternal impatience once more becomes strong.

Even the young just out of the brood‑sac build their own nests and enlarge them as their growth requires. But the young seem to spend less time than the adults do inside their nests, and to creep about more freely over the weeds. It is common to see several tiny nests built close to the home of a large amphipod; perhaps the young like to stay close to the mother even after they have been ejected from her nest.

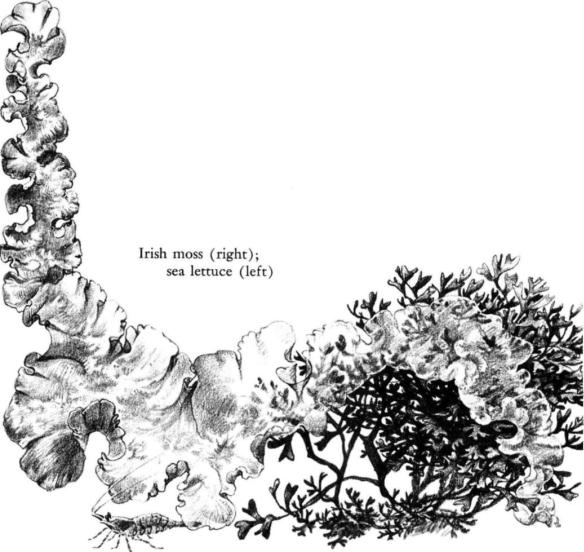

At low tide the water falls below the rockweeds and the mussels and enters a broad band clothed with the reddish‑brown turf of the Irish moss. The time of its exposure to the atmosphere is so brief, the retreat of the sea so fleeting, that the moss retains a shining freshness, a wetness, and a sparkle that speak of its recent contact with the surf. Perhaps because we can visit this area only in that brief and magical hour of the tide’s turning, perhaps because of the nearness of waves breaking on rocky rims, dissolving in foam and spray, and pouring seaward again to the accompaniment of many water sounds, we are reminded always that this low‑tide area is of the sea and that we are trespassers.

Here, in this mossy turf, life exists in layers, one above another; life exists on other life, or within it, or under it, or above it. Because the moss is low‑growing and branches profusely and intricately, it cushions the living things within it from the blows of the surf, and holds the wetness of the sea about them in these brief intervals of the low ebbing of the tide. After I have visited the shore and then at night have heard the surf trampling in over these moss‑grown ledges with the heavy tread of the fall tides, I have wondered about the baby starfish, the urchins, the brittle stars, the tube‑dwelling amphipods, the nudibranchs, and all the other small and delicate fauna of the moss; but I know that if there is security in their world it should be here, in this densest of intertidal jungles, over which the waves break harmlessly.

The moss forms so dense a covering that one cannot see what is beneath without intimate exploration. The abundance of life here, both in species and individuals, is on a scale that is hard to grasp. There is scarcely a stem of Irish moss that is not completely encased with one of the bryozoan sea mats–the white lacework of Membranipora or the glassy, brittle crust of Microporella. Such a crust consists of a mosaic of almost microscopic cells or compartments, arranged in regular rows and patterns, their surfaces finely sculptured. Each cell is the home of a minute, tentacled creature. By a conservative guess, several thousand such creatures live on a single stem of moss. On a square foot of rock surface there are probably several hundred such stems, providing living space for about a million of the bryozoans. On a stretch of Maine shore that the eye can take in at a glance, the population must run into the trillions for this single group of animals.

But there are further implications. If the population of the sea laces is so immense, that of the creatures they feed upon must be infinitely greater. A bryozoan colony acts as a highly efficient trap or filter to remove minute food animals from the sea water. One by one, the doors of the separate compartments open and from each a whorl of petal‑like filaments is thrust out. In one moment the whole surface of the colony may be alive with crowns of tentacles swaying like flowers in a windswept field; the next instant, all may have snapped back into their protective cells and the colony is again a pavement of sculptured stone. But while the “flowers” sway over the stone field each spells death for many beings of the sea, as it draws in the minute spheres and ovals and crescents of the protozoans and the smallest algae, perhaps also some of the smallest of crustaceans and worms, or the larvae of mollusks and starfish, all of which are invisibly present in this mossy jungle, in numbers like the stars.

Larger animals are less numerous but still impressively abundant. Sea urchins, looking like large green cockleburs, often lie deep within the moss, their globular bodies anchored securely to the underlying rock by the adhesive discs of many tube feet. The ubiquitous common periwinkles, in some curious way unaffected by the conditions that confine most intertidal animals to certain zones, live above, within, and below the moss zone. Here their shells lie about over the surface of the weed at low tide; they hang heavily from its fronds, ready to drop at a touch.

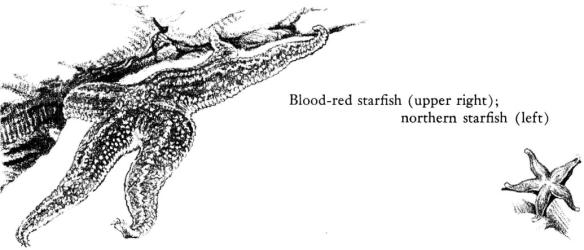

And young starfish are here by the hundred, for these meadows of moss seem to be one of the chief nurseries for the starfish of northern shores. In the fall almost every other plant shelters quarter‑inch and half‑inch sizes. In these youthful starfish there are color patterns that become obliterated in maturity. The tube feet, the spines, and all the other curious epidermal outgrowths of these spiny‑skinned creatures are large in proportion to the total size and have a clean perfection of form and structure.

On the rocky floor among the plant stems lie the infant stars. They are white insubstantial specks, in size and delicate beauty like snowflakes. There is an obvious newness about them, proclaiming that they have undergone their metamorphosis from the larval form to the adult shape only recently.

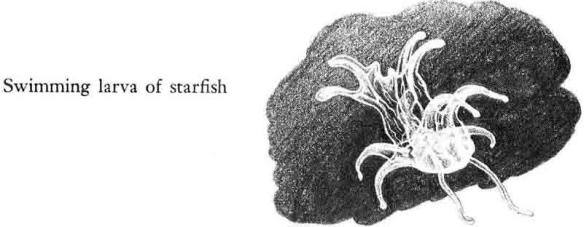

Perhaps it was on these very rocks that the swimming larvae, completing their period of life in the plankton, came to rest, attaching themselves firmly and becoming for a brief period sedentary animals. Then their bodies were like blown glass from which slender horns projected; the horns or lobes were covered with cilia for swimming and some of them bore suckers for use when the larvae should seek the firm underlying floor of the sea. During the short but critical period of attachment, the larval tissues were reorganized as completely as those of a pupal insect within a cocoon, the infant shape disappeared and in its place the five‑rayed body of the adult was formed. Now as we find them, these new‑made starfish use their tube feet competently, creeping over the rocks, righting their bodies if by mischance they are overturned, even, we may suppose, finding and devouring minute food animals in true starfish fashion.

The northern starfish lives in almost every low tide pool or waits out the tidal interval in wet moss or in the dripping coolness of a rock overhang. On a very low tide, when the departure of the sea is brief, these stars strew their variously hued forms over the moss like so many blossoms–pink, blue, purple, peach, or beige. Here and there is a gray or orange starfish on which the spines stand out conspicuously in a pattern of white dots. Its arms are rounder and firmer than those of the northern star and the round stony plate on its upper surface is usually a bright orange instead of pale yellow as in the northern species. This starfish is common south of Cape Cod and only a few individuals stray farther north. Still a third species inhabits these low‑tide rocks–the blood‑red starfish, Henricia, whose kind not only lives at these margins of the sea but goes down to lightless sea bottoms near the edge of the continental shelf. It is always an inhabitant of cool waters and south of Cape Cod must go offshore to find the temperatures it requires. But its dispersal is not, as one might suppose, by the larval stages, for unlike most other starfish it produces no swimming young; instead, the mother holds the eggs and the young that develop from them in a pouch formed by her arms as she assumes a humped position. Thus she broods them until they have become fully developed little starfish.

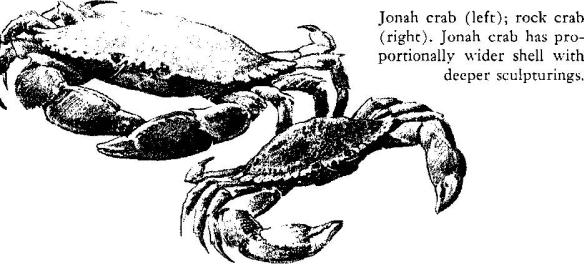

The Jonah crabs use the resilient cushion of moss as a hiding place to wait for the return of the tide or the coming of darkness. I remember a moss‑carpeted ledge standing out from a rock wall, jutting out over sea depths where Laminaria rolled in the tide. The sea had only recently dropped below this ledge; its return was imminent and in fact was promised by every glassy swell that surged smoothly to its edge, then fell away. The moss was saturated, holding the water as faithfully as a sponge. Down within the deep pile of that carpet I caught a glimpse of a bright rosy color. At first I took it to be a growth of one of the encrusting corallines, but when I parted the fronds I was startled by abrupt movement as a large crab shifted its position and lapsed again into passive waiting. Only after search deep in the moss did I find several of the crabs, waiting out the brief interval of low tide and reasonably secure from detection by the gulls.

The seeming passivity of these northern crabs must be related to their need to escape the gulls–probably their most persistent enemies. By day one always has to search for the crabs. If not hidden deeply within the seaweeds, they may be wedged in the farthest recess afforded by an overhanging rock, secure there, in dim coolness, gently waving their antennae and waiting for the return of the sea. In darkness, however, the big crabs possess the shore. One night when the tide was ebbing I went down to the low‑tide world to return a large starfish I had taken on the morning tide. The starfish was at home at the lowest level of these tides of the August moon, and to that level it must be returned. I took a flashlight and made my way down over the slippery rockweeds. It was an eerie world; ledges curtained with weed and boulders that by day were familiar landmarks seemed to loom larger than I remembered and to have assumed unfamiliar shapes, every projecting mass thrown into bold relief by the shadows. Everywhere I looked, directly in the beam of my flashlight or obliquely in the half‑illuminated gloom, crabs were scuttling about. Boldly and possessively they inhabited the weed‑shrouded rocks. All the grotesqueness of their form accentuated, they seemed to have transformed this once familiar place into a goblin world.

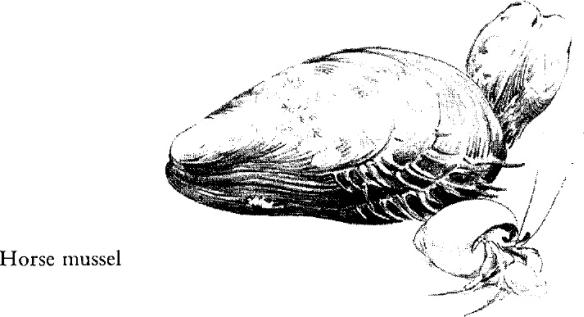

In some places, the moss is attached, not to the underlying rock, but to the next lower layer of life, a community of horse mussels. These large mollusks inhabit heavy, bulging shells, the smaller ends of which bristle with coarse yellow hairs that grow as excrescences from the epidermis. The horse mussels themselves are the basis of a whole community of animals that would find life on these wave‑swept rocks impossible except for the presence and activities of the mollusks. The mussels have bound their shells to the underlying rock by an almost inextricable tangle of golden‑hued byssus threads. These are the product of glands in the long slender foot, the threads being “spun” from a curious milky secretion that solidifies on contact with sea water. The threads possess a texture that is a remarkable combination of toughness, strength, softness, and elasticity; extending out in all directions they enable the mussels to hold their position not only against the thrust of incoming waves but also against the drag of the backwash, which in a heavy surf is tremendous.

Over the years that the mussels have been growing here, particles of muddy debris have settled under their shells and around the anchor lines of the byssus threads. This has created still another area for life, a sort of understory inhabited by a variety of animals including worms, crustaceans, echinoderms, and numerous mollusks, as well as the baby mussels of an oncoming generation–these as yet so small and transparent that the forms of their infant bodies show through newly formed shells.

Certain animals almost invariably live among the horse mussels. Brittle stars insinuate their thin bodies among the threads and under the shells of the mussels, gliding with serpentine motions of the long slender arms. The scale worms always live here, too, and down in the lower layers of this strange community of animals starfish may live below the scale worms and brittle stars, and sea urchins below the starfish, and sea cucumbers below the urchins.

Of the echinoderms that live here, few are the largest individuals of their species. The blanket of horse mussels seems to be a shelter for young, growing animals, and indeed the full‑grown starfish and urchins could hardly be accommodated there. In the waterless intervals of the low tide, the cucumbers draw themselves into little football‑shaped ovals scarcely more than an inch long; returned to the water and fully relaxed, they extend their bodies to a length of five or six inches and unfurl a crown of tentacles. The cucumbers are detritus feeders, and explore the surrounding muddy debris with their soft tentacles, which periodically they pull back and draw across their mouths, as a child would lick his fingers.

In pockets deep in the moss under layers of mussels, a long, slender little fish of the blenny tribe, the rock eel, waits for the return of the tide, coiled in its water‑filled refuge with several of its kind. Disturbed by an intruder, all thrash the water violently, squirming with eel‑like undulations to escape.

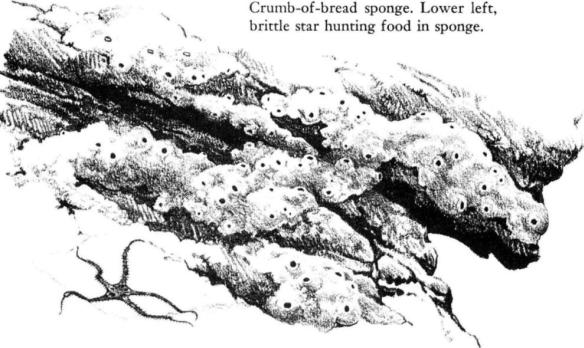

Where the big mussels grow more sparsely, in the seaward suburbs of this mussel city, the moss carpet, too, becomes a little thinner; but still the underlying rock seldom is exposed. The green crumb‑of‑bread sponge, which at higher levels seeks the shelter of rock overhangs and tide pools, here seems able to face the direct force of the sea and forms soft, thick mats of pale green, dotted with the cones and craters typical of this species. And here and there patches of another color show amid the thinning moss–dull rose or a gleaming, reddish brown of satin finish–an intimation of what lies at lower levels.

During much of the year the spring tides drop down into the band of Irish moss but go no lower, returning then toward the land. But in certain months, depending on the changing positions of sun and moon and earth, even the spring tides gain in amplitude, and their surge of water ebbs farther into the sea even as it rises higher against the land. Always, the autumn tides move strongly, and as the hunter’s moon waxes and grows round, there come days and nights when the flood tides leap at the smooth rim of granite and send up their lace‑edged wavelets to touch the roots of the bayberry; on their ebbs, with sun and moon combining to draw them back to the sea, they fall away from ledges not revealed since the April moon shone upon their dark shapes. Then they expose the sea’s enameled floor–the rose of encrusting corallines, the green of sea urchins, the shining amber of the oarweeds.

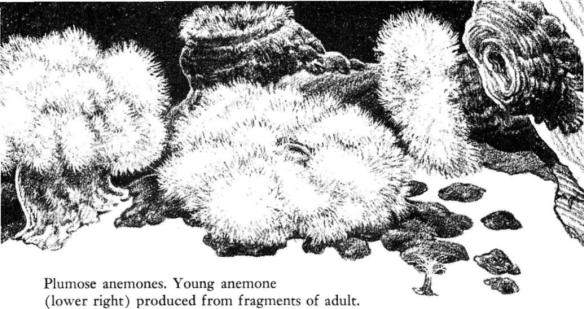

At such a time of great tides I go down to that threshold of the sea world to which land creatures are admitted rarely in the cycle of the year. There I have known dark caves where tiny sea flowers bloom and masses of soft coral endure the transient withdrawal of the water. In these caves and in the wet gloom of deep crevices in the rocks I have found myself in the world of the sea anemones–creatures that spread a creamyhued crown of tentacles above the shining brown columns of their bodies, like handsome chrysanthemums blooming in little pools held in depressions or on bottoms just below the tide line.

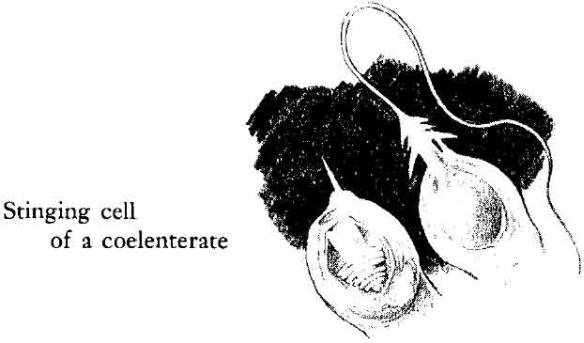

Where they are exposed by this extreme ebbing of the water, their appearance is so changed that they seem not meant for even this brief experience of land life. Wherever the contours of this uneven sea floor provide some shelter I have found their exposed colonies–dozens or scores of anemones crowded together, their translucent bodies touching, side against side. The anemones that cling to horizontal surfaces respond to the withdrawal of water by pulling all their tissues down into a flattened, conical mass of firm consistency. The crown of feather‑soft tentacles is retracted and tucked within, with no suggestion of the beauty that resides in an expanded anemone. Those that grow on vertical rocks hang down limply, extended into curious, hourglass shapes, all their tissues flaccid in the unaccustomed withdrawal of water. They do not lack the ability to contract, for when they are touched they promptly begin to shorten the column, drawing it up into more normal proportions. These anemones, deserted by the sea, are bizarre objects rather than things of beauty, and indeed bear only the most remote resemblance to the anemones blooming under water just offshore, all their tentacles expanded in the search for food. As small water creatures come in contact with the tentacles of these expanded anemones, they receive a deadly discharge. Each of the thousand or more tentacles bears thousands of coiled darts embedded in its substance, each with a minute spine protruding. The spine may act as a trigger to set off the explosion, or perhaps the very nearness of prey acts as a sort of chemical trigger, causing the dart to explode with great violence, impaling or entangling its victim and injecting a poison.

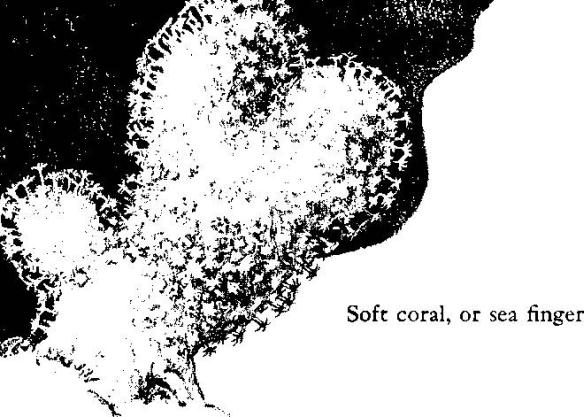

Like the anemones, the soft coral hangs its thimble‑sized colonies on the under side of ledges. Limp and dripping at low tide, they suggest nothing of the life and beauty to which the returning water restores them. Then from all the myriad pores of the surface of the colony, the tentacles of little tubular animals appear and the polyps thrust themselves out into the tide, seizing each for itself the minute shrimps and copepods and multiformed larvae brought by the water.

The soft coral, or sea finger, secretes no limy cups as the distantly related stony, or reef, corals do, but forms colonies in which many animals live embedded in a tough matrix strengthened with spicules of lime. Minute though the spicules are, they become geologically important where, in tropical reefs, the soft corals, or Alcyonaria, mingle with the true corals. With the death and dissolution of the soft tissues, the hard spicules become minute building stones, entering into the composition of the reef. Alcyonarians grow in lush profusion and variety on the coral reefs and flats of the Indian Ocean, for these soft corals are predominantly creatures of the tropics. A few, however, venture into polar waters. One very large species, tall as a tall man and branched like a tree, lives on the fishing banks off Nova Scotia and New England. Most of the group live in deep waters; for the most part the intertidal rocks are inhospitable to them and only an occasional low‑lying ledge, rarely and briefly exposed on the low spring tides, bears their colonies on dark and hidden surfaces.

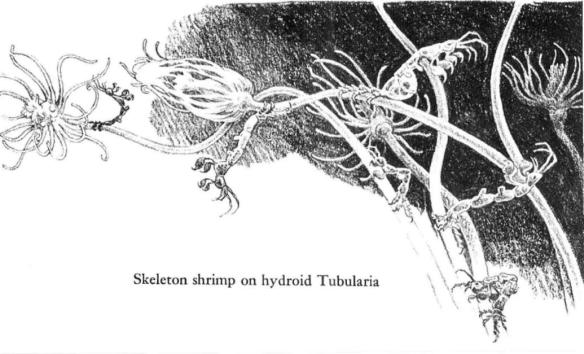

In seams and crevices of rock, in little water‑filled pools, or on rock walls briefly exposed by the tide’s low ebbing, colonies of the pink‑hearted hydroid Tubularia form gardens of beauty. Where the water still covers them the flowerlike animals sway gracefully at the ends of long stalks, their tentacles reaching out to capture small animals of the plankton. Perhaps it is where they are permanently submerged, however, that they reach their fullest development. I have seen them coating wharf pilings, floats, and submerged ropes and cables so thickly that not a trace of the substratum could be seen, their growth giving the illusion of thousands of blossoms, each as large as the tip of my little finger.

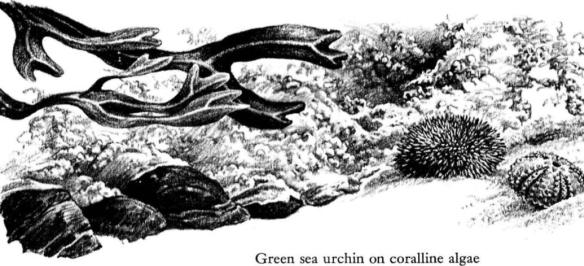

Below the last clumps of Irish moss, a new kind of sea bottom is exposed. The transition is abrupt. As though a line had been drawn, suddenly there is no more moss, and one steps from the yielding brown cushion onto a surface that seemingly is of stone. Except that the color is wrong, the effect is almost that of a volcanic slope–there is the same barren nakedness. Yet this is not rock that we see. The underlying rock is coated on every surface, vertical or horizontal, exposed or hidden, with a crust of coralline algae, so that it wears a rich old‑rose color. So intimate is the union that the plant seems part of the rock. Here the periwinkles wear little patches of pink on their shells, all the rock caverns and fissures are lined with the same color, and the rock bottom that slants away into green water carries down the rose hue as far as the eye can follow.

The coralline algae are plants of unusual fascination. They belong to the group of red seaweeds, most of which live in the deeper coastal waters, for the chemical nature of their pigments usually requires the protection of a screen of water between their tissues and the sun. The corallines, however, are extraordinary in their ability to withstand direct sunlight. They are able to incorporate carbonate of lime into their tissues so that they have become hardened. Most species form encrusting patches on rocks, shells, and other firm surfaces. The crust may be thin and smooth, suggesting a coat of enamel paint; or it may be thick and roughened by small nodules and protuberances. In the tropics the corallines often enter importantly into the composition of the coral reefs, helping to cement the branching structures built by the coral animals into a solid reef. Here and there in the East Indies they cover the tidal flats as far as eye can see with their delicately hued crusts, and many of the “coral reefs” of the Indian Ocean contain no coral but are built largely of these plants. About the coasts of Spitsbergen, where under the dimly lit waters of the north the great forests of the brown algae grow, there are also vast calcareous banks, stretching mile after mile, formed by the coralline algae. Being able to live not only in tropical warmth but where water temperatures seldom rise above the freezing point, these plants flourish all the way from Arctic to Antarctic seas.

Where these same corallines paint a rose‑colored band on the rocks of the Maine coast, as though to mark the low water line of the lowest spring tides, visible animal life is scarce. But although little else lives openly in this zone, thousands of sea urchins do. Instead of hiding in crevices or under rocks as they do at the higher levels, they live fully exposed on the flat or gently shelving rock faces. Groups of a score or half a hundred individuals lie together on the coralline‑coated rocks, forming patches of pure green on the rose background. I have seen such herds of urchins lying on rocks that were being washed by a heavy surf, but apparently all the little anchors formed by their tube feet held securely. Though the waves broke heavily and poured back in a turbulent rush of waters, there the urchins remained undisturbed. Perhaps the strong tendency to hide and to wedge themselves into crevices and under boulders, as displayed by urchins in tide pools or up in the rockweed zone, is not so much an attempt to avoid the power of the surf as a means of escaping the eager eyes of the gulls, who hunt them relentlessly on every low tide. This coralline zone where the urchins live so openly is covered almost constantly with a protective layer of water; probably not more than a dozen daytime tides in the entire year fall to this level. At all other times, the depth of water over the urchins prevents the gulls from reaching them, for although a gull can make shallow plunges under water, it cannot dive as a tern does, and probably cannot reach a bottom deeper than the length of its own body.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 1116;