Photographs 1 страница

Stealth bomber . Used for the first time in combat during Allied Force after having been in line service since 1993, a USAF B‑2 prepares to take on fuel midway across the Atlantic Ocean during one of two preplanned tanker hookups en route to target. The low‑observable bomber, operating nonstop from its home base in the United States, was the first allied aircraft to penetrate Serb defenses on opening night.

Safe recovery . An F‑117 stealth attack aircraft lands at Aviano Air Base, Italy, just after sunrise following a night mission into the most heavily defended portions of Serbia. During the air warТs fourth night, an F‑117 was downed just northwest of Belgrade, most likely by a lucky SA‑3 shot, in the first‑ever loss of a stealth aircraft in combat. (The pilot was promptly retrieved by CSAR forces.)

Heavy players . A venerable USAF B‑52H bomber stands parked on the ramp at RAF Fairford, England, as a successor‑generation B‑1B takes off on a mission to deliver as many as 80 500‑lb Mk 82 bombs or 30 CBU‑87 cluster bomb units against enemy barracks and other area targets. An AGM‑86C CALCM fired from standoff range by a B‑52 was the first allied weapon to be launched in the war.

Final checks . Two Block 40 F‑16CGs from the 555th Fighter Squadron at Aviano taxi into the arming area just short of the runway for one last look by maintenance technicians before taking off on a day mission to drop 500‑lb GBU‑12 laser‑guided bombs on УflexФ targets of opportunity in Serbia or Kosovo, as directed by airborne FACs and as approved, in some cases, by the CAOC.

Burner takeoff . An F‑15E from the 494th Fighter Squadron home‑based at RAF Lakenheath, England, clears the runway at Aviano in full afterburner, with CBU‑87 cluster munitions shown mounted on its aftmost semiconformal fuselage weapons stations. Eventually, some F‑15E strike sorties into Serbia and Kosovo were flown nonstop to target and back directly from Lakenheath.

On the cat . A U.S. Navy F/A‑18C assigned to Fighter/Attack Squadron 15 is readied for a catapult launch for an Allied Force day combat mission from the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt cruising on station in the Adriatic Sea. On April 15, carrier‑based F/A‑18s figured prominently in a major CAOC‑directed air strike on the Serb air base at Podgorica, Montenegro.

SAM hunter . This Block 50 F‑16CJ in the arming area at Aviano shows an AGM‑88 high‑speed antiradiation missile (HARM) mounted on the left intermediate wing weapons station, with an AIM‑9M air‑to‑air missile on the outboard station and an AIM‑120 AMRAAM on the wingtip missile rail. The USAFТs F‑16CJ inventory was stressed to the limit to meet the SEAD demand of Allied Force.

Combat support . U.S. Navy and Marine Corps EA‑6B Prowler electronic warfare aircraft, like this one shown taxiing for takeoff at Aviano, provided extensive and indispensable standoff jamming of enemy early warning and IADS fire‑control radars to help ensure unmolested allied strike operations, including B‑2 and F‑117 stealth operations, against the most heavily defended enemy targets in Serbia.

Task Force Hawk . A U.S. Army AH‑64 Apache attack helicopter flares for landing at the Rinas airport near Tirana, Albania, following a ferry flight from its home base at Illesheim, Germany. In all, 24 Apaches were dispatched to Albania with the intent to be used in Operation Allied Force, but none saw combat in the end because of concerns for the aircraftТs prospects for survival in hostile airspace.

Cramped spaces . This USAF C‑17 parked on the narrow ramp at Rinas airport, incapable of accommodating the larger C‑5, was one of many such aircraft which provided dedicated mobility service to TF Hawk. In more than 500 direct‑delivery lift sorties altogether, C‑17s moved 200,000‑plus short tons of equipment and supplies to support the ArmyТs deployment within the span of just a month.

Eagle eye . Ground crewmen at RAF Lakenheath prepare a LANTIRN targeting pod to be mounted on an F‑15E multirole, all‑weather fighter. The pod, also carried by the Navy F‑14D and the USAF F‑16CG, contains a forward‑looking infrared (FLIR) sensor for target identification at standoff ranges day or night, as well as a self‑contained laser designator for enabling precision delivery of LGBs.

Deadly force . Munitions technicians at RAF Fairford prepare a CBU‑87 cluster bomb unit for loading into a USAF B‑1B bomber in preparation for a mission against fielded Serbian forces operating in Kosovo. With a loadout of 30 CBU‑87sЦmore than five times the payload of an F‑15EЦthe B‑1 can fly at fighter‑equivalent speeds more than 4,200 nautical miles unrefueled.

Help from an ally . One of 18 CF‑18 Hornet multirole fighters deployed in support of Allied Force from Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, Alberta, Canada, is parked in front of a hardened aircraft shelter at Aviano. The aircraft mounts two 500‑lb GBU‑12 laser‑guided bombs on the outboard wing pylons and two AIM‑9M air‑to‑air missiles on the wingtip rails.

Force protection . A security guard stands watch over a USAF C‑17 airlifter at the Rinas airport in support of the U.S. ArmyТs Apache attack helicopter deployment to Albania. For a time, reported differences between on‑scene Air Force and Army commanders with respect to who was ultimately responsible for the airfield made for discomfiting friction within the U.S. contingent.

Flexing into the KEZ . An AGM‑65 Maverick‑equipped A‑10 from the USAFТs 52nd Fighter Wing stationed at Spangdahlem Air Base, Germany, takes off from Gioia del Colle to provide an on‑call capability against possible Serb targets detected in Kosovo by allied sensors, including the TPQ‑36 and TPQ‑37 firefinder radars operated by the U.S. Army on the high ground above Tirana, Albania.

Round‑the‑clock operations . An F‑16 pilot readies himself for a night mission over Serbia, his helmet shown fitted with a mount for night‑vision goggles. Used in conjunction with compatible cockpit lighting, NVGs made possible night tactics applications, including multiaircraft formations and simultaneous bomb deliveries, which otherwise could only have been conducted during daylight.

Night refueling . A USAF F‑15C air combat fighter, shown here through a night‑vision lens, moves into the precontact position to take on fuel from a KC‑135 tanker before resuming its station to provide offensive counterair protection for attacking NATO strikers. With a loss of six MiGs in aerial combat encounters the first week, Serb fighters rarely rose thereafter to challenge NATOТs control of the air.

Splash one Fulcrum . A team of U.S. military personnel examines the remains of an enemy MiG‑29 fighter (NATO code name Fulcrum) which was shot down in Bosnian airspace by a USAF F‑15C on the afternoon of March 26, 1999. The downed aircraft, which appeared to have strayed from its planned course due to a loss of situation awareness by its pilot, brought to five the number of MiG‑29s destroyed in early Allied Force air encounters.

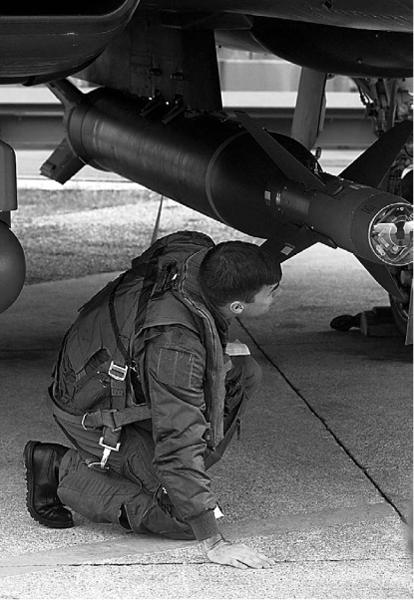

Hard‑target killer . This F‑15E pilot, a USAF major assigned to the 494th Fighter Squadron, looks over a 4,700‑lb electro‑optically‑guided GBU‑28 bunker‑buster munition mounted on his aircraftТs centerline stores station. The aircraft, one of a two‑ship flight of F‑15Es (call sign Lance 31 and 32), delivered the weapon on April 28, 1999, against an underground hangar at the Serb air base at Podgorica.

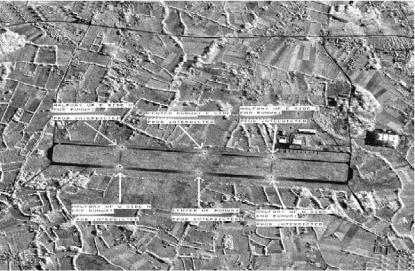

Precision attack . In April 1999, a single B‑2 achieved six accurately placed GBU‑31 JDAM hits against six runway‑taxiway intersections at the Obvra military airfield in Serbia, precluding operations by enemy fighters until repairs could be completed. This post‑strike image graphically shows the B‑2Тs ability with JDAM to achieve the effects of mass without having to mass, regardless of weather.

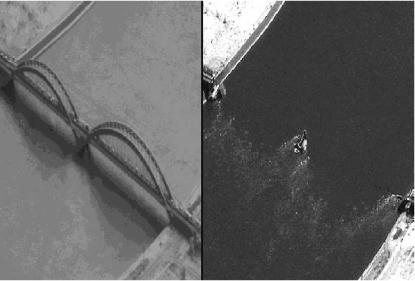

A bridge no more . Another post‑strike battle‑damage assessment image shows this bridge in Serbia cut in two places by a precision bombing attack. Sometimes enemy bridges were dropped at the behest of NATO target planners to prevent the flow of traffic over them. At other times, they were attacked and damaged to sever key fiber‑optic communications lines that were known to run through them.

Before and after . This bridge over the Danube River near Novi Sad in Serbia, shown here in both pre‑ and post‑strike imagery, was all but completely demolished by precision bombing on Day 9 of Allied Force as Phase III of the air war, for the first time, ramped up operations to include attacks against not only Serbian IADS and fielded military assets but also key infrastructure targets.

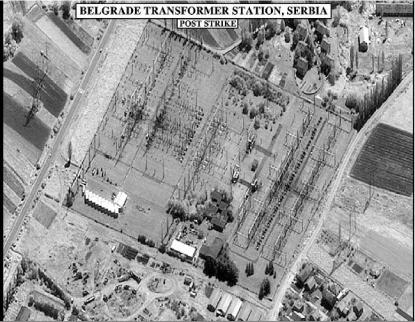

Effects‑based targeting . For three consecutive nights beginning on May 24, U.S. aircraft struck electrical power facilities in Belgrade, Novi Sad, and Nis, the three largest cities in Serbia, shutting off electrical power to 80 percent of Serbia. This transformer yard in Belgrade was one such target that was attacked in what was arguably the most influential strike of Allied Force to that point.

[1]Christopher Cviic, УA Victory All the Same,Ф Survival , Summer 2000, p. 174.

[2]In the latter respect, this assessment consciously seeks to avoid the common syndrome of so‑called lessons‑learned efforts whereby Уlosers tend to study what went wrong while winners study what went right.Ф Princeton University political scientist Bernard Lewis, an adviser to the USAFТs Gulf War Air Power Survey conducted in 1991Ц1992, called this cautionary reminder to the attention of the survey team as that effort was getting under way. Quoted in Gian P. Gentile, How Effective Is Strategic Bombing? Lessons Learned from World War II to Kosovo , New York, New York University Press, 2001, p. 182.

[3]For informed insight into the origins of the ancestral hatreds that animated the atrocities committed against the Kosovar Albanians by Serbia, one can do no better than the epic novel by Ivo Andric, The Bridge on the Drina , Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1977. Written in Serbo‑Croatian in 1945, this tour de force won the 1961 Nobel prize for literature. It speaks about Balkan conflicts from the earliest clashes between the Bosnian Turks and Serb Christians in the early 15th century to the coming of the First World War. In a passage hauntingly reminiscent of more recent Balkan horrors, Andric described how ethnic rivals as far back as the 17th century Уwere as if drunk with bitterness, from desire for vengeance, and longed to punish and kill whomsoever they could, since they could not punish or kill those whom they wishedФ (pp. 86Ц87). Of a later generation looking at the redrawn map of Bosnia after the Balkan war of 1912, Andric likewise wrote that they Уsaw nothing in those curving lines, but they knew and understood everything, for their geography was in their blood and they felt biologically their picture of the worldФ (p. 229). A balanced synopsis of this history that places it in the context of the 20th‑century developments that led up to the 1999 Kosovo crisis is presented in William W. Hagen, УThe BalkansТ Lethal Nationalisms,Ф Foreign Affairs , July/August 1999, pp. 52Ц64. For more on this background, see Ivo H. Daalder and Michael E. OТHanlon, Winning Ugly: NATOТs War to Save Kosovo , Washington, D.C., Brookings Institution, 2000, pp. 1Ц100. See also Michael Ignatieff, Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond , New York, Metropolitan Books, 2000, especially pp. 11Ц65; Misha Glenny, The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1809Ц1999 , New York, Penguin Books, 2000; and Tim Judah, Kosovo: War and Revenge , New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2000.

[4]Today, Serbia and Montenegro (the latter is semiautonomous) are all that remain of the former Yugoslavia.

[5]The expulsion order was later rescinded by Milosevic.

[6]On this point, NATOТs Secretary General, Javier Solana, remarked that a Serb diplomat had been heard to cite a rule of thumb to the effect that Уa village a day would keep NATO away.Ф

[7]In his exchange with Milosevic, Holbrooke said: УYou understand our position?Ф Milosevic: УYes.Ф Holbrooke: УIs it absolutely clear what will happen when we leave, given your position?Ф Milosevic: УYes, you will bomb us. You are a big and powerful nation. You can bomb us if you wish.Ф Bruce W. Nelan, УInto the Fire,Ф Time , April 5, 1999, p. 35. Later, Holbrooke added that Milosevic was Уtricky, evasive, smart, and dangerous,Ф further noting that his mood in the final confrontation was Уcalm, almost fatalistic, unyielding.Ф УСHe Was Calm, Unyielding,ТФ Newsweek , April 5, 1999, p. 37.

[8]Jane Perlez, УHolbrooke to Meet Milosevic in Final Peace Effort,Ф New York Times , March 22, 1999.

[9]R. Jeffrey Smith, УBelgrade Rebuffs Final U.S. Warning,Ф Washington Post , March 23, 1999.

[10]Charles Babington and Helen Dewar, УPresident Pleads for Support,Ф Washington Post , March 24, 1999.

[11]Telephone conversation with Lieutenant General Michael Short, USAF (Ret.), August 22, 2001.

[12]Flexible Anvil was a U.S.‑only option that envisaged only ship‑launched Tomahawk and conventional air‑launched cruise missile attacks over a 48‑ to 72‑hour period, roughly along the lines of Operation Desert Fox conducted against Iraq the following December. Sky Anvil envisaged follow‑on air strikes in a transition to a NATO operation (or an operation involving a more truncated coalition of the willing). General Short believed that it was counterproductive to fragment these closely connected options into two separate plans, but he and Admiral Murphy were well acquainted and kept each other informed. Conversation with Vice Admiral Daniel J. Murphy, USN, commander, 6th Fleet, aboard the USS LaSalle , Gaeta, Italy, June 8, 2000.

[13]Lieutenant Colonel L. T. Wight, USAF, УWhat a Tangled Web We Wove: An After‑Action Assessment of Operation Allied ForceТs Command and Control Structure and Processes,Ф unpublished paper, p. 1.

[14]General John Jumper, USAF, testimony to the Military Readiness Subcommittee, House Armed Services Committee, Washington, D.C., October 26, 1999. The most fully developed of these iterations, called Operation Allied Talon, was a true phased air campaign plan rooted in effects‑based targeting and aimed at achieving concrete military objectives. Despite the best efforts of the JTF Noble Anvil leadership (Admiral James Ellis, General Jumper, and General Short) to sell this plan to SACEUR, General Clark never adopted it. Instead, he elected to cut and paste different elements of the different plans that he thought were most appropriate and labeled the resultant product Operation Allied Force. Comments on an earlier draft by Hq USAFE/SA, April 6, 2001. General Jumper himself later confirmed that Allied Talon was a nonstarter. Conversation with General John P. Jumper, USAF, Hq Air Combat Command, Langley AFB, Virginia, May 15, 2001.

[15]Charles Babington and William Drozdiak, УBelgrade Faces the 11th Hour, Again,Ф Washington Post , March 22, 1999. For more first‑hand comment on the intra‑NATO politics that preceded Allied Force, see General Wesley K. Clark, Waging Modern War: Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Future of Combat , New York, Public Affairs, 2001, especially pp. 121Ц189.

[16]William Drozdiak, УPolitics Hampered Warfare, Clark Says,Ф Washington Post , July 20, 1999.

[17]This should not be taken to suggest that NATOТs air war against Serbia was a unilateral action undertaken without regard for the UN whatsoever. On the contrary, in March 1998 the Security Council had expressly recognized in Resolution 1160 that the Serb governmentТs repression of the ethnic Albanian population in Kosovo constituted a threat to international peace and security, a view later repeated in Resolution 1199 six months before the start of Allied Force, which called for action aimed at heading off Уthe impending humanitarian catastropheФ in Kosovo. As an IISS comment later noted, NATOТs air war for Kosovo thus constituted Уa highly significant precedent,Ф in that it established Уmore firmly in international law the right to intervene on humanitarian grounds, even without an express mandate from the Security Council.Ф Strategic Survey 1999/2000 , London, England, The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2000, p. 26.

[18]Jane Perlez, УU.S. Option: Air Attacks May Prove Unpalatable,Ф New York Times , March 23, 1999.

[19]Steven Erlanger, УU.S. Issues Appeal to Serbs to Halt Attack in Kosovo,Ф New York Times , March 23, 1999.

[20]УAWOS [Air War Over Serbia] Fact Sheet,Ф Hq USAFE/SA, December 17, 1999. See also The Military Balance, 1998/99 , London, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1998, p. 100.

[21]Discussions with former East European strategic and tactical SAM operators on IADS visual observer employment doctrine, as reported to the author by Hq USAFE/IN, May 18, 2001.

[22]John Diamond, УYugoslavia, Iraq Talked Air Defense Strategy,Ф Philadelphia Inquirer , March 30, 1999.

[23]Michael R. Gordon, УNATO to Hit Serbs from 2 More Sides,Ф New York Times , May 11, 1999. This last system featured the Bofors 40mm gun tied to the Giraffe radar‑based low‑altitude air defense system (LAADS). It was the only radar‑cued (as opposed to radar‑directed) AAA weapon fielded in the war zone and possibly the most potent low‑altitude AAA threat because of its local Giraffe‑based LAADS command and control system. Peter Rackham, ed., JaneТs C4I Systems, 1994Ц95 , London, JaneТs Information Group, 1994, p. 107.

[24]Paul Richter, УU.S. Pilots Face Perilous Task, Pentagon Says,Ф Los Angeles Times , March 20, 1999. In testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on the eve of the war, Ryan added: УI ran the air campaign in Bosnia, and this defensive array is much more substantiveЕ two or three times more so. It is deep and redundant. Those guys [in Bosnia] were good, but these guys are better. There is a very real possibility we will lose aircraft trying to take it on.Ф David Atkinson, УStealth Could Play Key Role in Kosovo, Despite Bad Weather,Ф Defense Daily , March 23, 1999, p. 1.

[25]Bruce W. Nelan, УInto the Fire,Ф Time , April 5, 1999, p. 31.

[26]Francis X. Clines, УNATO Opens Broad Barrage Against Serbs as Clinton Denounces СBrutal Repression,ТФ New York Times , March 25, 1999.

[27]Paul Richter, УTime Is Not on the Side of U.S., Allies,Ф Los Angeles Times , March 25, 1999.

[28]John T. Correll, УAssumptions Fall in Kosovo,Ф Air Force Magazine , June 1999, p. 4.

[29]This study has taken special care to characterize Operation Allied Force as an Уair warФ or an Уair effort,Ф rather than as a full‑fledged Уair campaign.Ф Although that effort continues to be widely portrayed as the latter, formal Air Force doctrine defines an air campaign as Уa connected series of operations conducted by air forces to achieve joint force objectives within a given time and area.Ф Air Force Basic Doctrine , Maxwell AFB, Alabama, Hq Air Force Doctrine Center, AFDD‑1, September 1997, p. 78. By that standard, NATOТs air war for Kosovo did not attain to the level of a campaign, as did the earlier Operations Desert Storm and Deliberate Force. Rather, it was a continuously evolving coercive operation featuring piecemeal attacks against unsystematically approved targets, not an integrated effort aimed from the outset at achieving predetermined and identifiable operational effects.

[30]The effectiveness of these initial standoff attacks was not impressive. During the first two weeks, no B‑52 succeeded in launching all eight of its CALCMs. In one instance, six out of eight were said to have failed. Also, the two times that B‑52s later fired the AGM‑142 Have Nap cruise missile, both launches were reportedly operational failures. See John D. Morrocco, David Fulghum, and Robert Wall, УWeather, Weapons Dearth Slow NATO Strikes,Ф Aviation Week and Space Technology , April 5, 1999, p. 26, and William M. Arkin, УKosovo Report Short on Weapons Performance Details,Ф Defense Daily , February 10, 2000, p. 2.

[31]An important qualification is warranted here. Although the opening‑night approved aim points largely entailed fixed IADS targets, the limited attacks conducted against them were not part of a phased campaign plan in which rolling back the enemy IADS was a priority. There was no strategic emphasis on IADS takedown in these attacks. Comments on an earlier draft by Hq USAFE/IN, May 18, 2001.

[32]Italian bases used included Aviano, Gioio del Colle, Villafranca, Amendola, Cervia, Gazzanise, Ghedi, Piacenza, Istrana, Falconara, Practica di Mare, Brindisi, and Sigonella. German bases used were Royal Air Force (RAF) Bruggen, Rhein Main Air Base (AB), Spangdahlem AB, and Ramstein AB. Bases made available by the United Kingdom were RAF Fairford, RAF Lakenheath, and RAF Mildenhall. Spain provided Moron AB, and France provided Istres. For a complete list of all participating allied air assets, their units, and their bases, as well as a tabulation of the Yugoslav IADS and air order of battle as of April 20, see Benoit Colin and Rene J. Francillon, УLТOTAN en Guerre!Ф Air Fan , May 1999, pp. 12Ц19. See also John E. Peters, Stuart Johnson, Nora Bensahel, Timothy Liston, and Traci Williams, European Contributions to Operation Allied Force: Implications for Transatlantic Cooperation , Santa Monica, California, RAND, MR‑1391‑AF, 2001.

[33]Robert Hewson, УOperation Allied Force: The First 30 Days,Ф World Air Power Journal , Fall 1999, p. 16.

[34]Nelan, УInto the Fire,Ф p. 32.

[35]Steven Lee Myers, УEarly Attacks Focus on Web of Air Defense,Ф New York Times , March 25, 1999.

[36]Comments on an earlier draft by Hq USAFE/IN, May 18, 2001.

[37]This suggested that the Serb IADS may have been unable to deconflict its SAMs and fighters operating in the same airspace because of identification and discrimination problems.

[38]Barton Gellman, УKey Sites Pounded for 2nd Day,Ф Washington Post , March 26, 1999. See also John D. Morrocco and Robert Wall, УNATO Vows Air Strikes Will Go the Distance,Ф Aviation Week and Space Technology , March 29, 1999, p. 34.

[39]Hewson, УOperation Allied Force,Ф p. 17.

[40]Telephone conversation with Lieutenant General Michael Short, USAF (Ret.), August 16, 2001.

[41]Hewson, УOperation Allied Force,Ф p. 18.

[42]John F. Harris, УClinton Saw No Alternative to Airstrikes,Ф Washington Post , April 1, 1999.

[43]Johanna McGeary, УThe Road to Hell,Ф Time , April 12, 1999, p. 42.

[44]For an informed treatment of the KLA and its origins, goals, and prospects by The New York Times Т Balkans bureau chief from 1995 to 1998, see Chris Hedges, УKosovoТs Next Masters?Ф Foreign Affairs , May/June 1999, pp. 24Ц42.

[45]Carla Anne Robbins, Thomas E. Ricks, and Neil King, Jr., УMilosevicТs Resolve Spawned Unity, Wider Bombing List in NATO Alliance,Ф Wall Street Journal , April 27, 1999. Unlike nearly all other NATO principals, General Naumann cautioned even before the air war began that although the intent was to be quick, Operation Allied Force could well turn out to be Уlong and protracted.Ф Paul Richter and John‑Thor Dahlburg, УNATO Broadens Its Battle Strategy,Ф Los Angeles Times , March 24, 1999.

[46]William Drozdiak, УNATO Leaders Struggle to Find a Winning Strategy,Ф Washington Post , April 1, 1999.

[47]The latter rumblings prompted concern in U.S. and NATO military circles that once any such pause might be agreed to, it would be that much more difficult to resume the bombing after the pause had expired. In the end, no pause in the bombing occurred at any time during Allied Force, other than those occasioned by bad weather.

[48]After careful examination, the provision of airlift relief missions for the Kosovar refugees was ruled out by U.S. and NATO planners because they were deemed excessively dangerous in the face of threats from enemy ground fire and because of concern that any delivered supplies would end up in the wrong hands.

[49]Bradley Graham and William Drozdiak, УAllied Action Fails to Stop Serb Brutality,Ф Washington Post , March 31, 1999.

[50]Craig R. Whitney, УOn 7th Day, Serb Resilience Gives NATO Leaders Pause,Ф New York Times , March 31, 1999.

[51]Of 10 known Serb SAMs that reportedly guided on B‑1s during the course of the air war, all were believed to have been successfully diverted to the decoys. See David Hughes, УA PilotТs Best Friend,Ф Aviation Week and Space Technology , May 31, 1999, p. 25. The commander of USAFE, General John Jumper, later explained the Serb IADS tactic employed: Radars in Montenegro would acquire and track the B‑1s as they flew in from over the Adriatic Sea, arced around Macedonia, and proceeded north into Kosovo. Those acquisition radars would then hand off their targets to SA‑6s, whose radars came up in full target‑track mode and fired the missiles, which headed straight for the ALE‑50 and took it out, just as the system was designed to work. УJumper on Air Power,Ф Air Force Magazine , July 2000, p. 43.

[52]Bradley Graham, УBombing Spreads,Ф Washington Post , March 29, 1999.

ƒата добавлени€: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1983;