middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 3 страница

The art from the Protogeometric and Geometric periods is modest in scope when compared to earlier and later art. The work that continued to be produced after the Bronze Age served a practical purpose, such as houses, textiles, and pottery, but in the archaeological record, it is only the latter that

survives in any quantity and degree of preservation. Looking at the style and quality of pottery, though, can reveal developments in the contemporary social fabric. Indeed, the utilitarian aspect of pottery means that whatever the material circumstances, pottery is needed for activities like cooking, storage, drinking, eating, and so on. The quality of a vessel’s fabric - the refinement of the clay, the way that it is formed into a shape, its decoration, the firing temperature, etc. - does not need to be high in order for a terracotta product to function. If a potter invests additional time and resources in the visual qualities and refinement of an object, and if a patron is willing to spend additional resources to acquire a decorated and higher-quality pot than one that is purely utilitarian, this can indicate something about the well-being of a society and the identity of its members. We can also see in pottery the emergence of distinct regional variations in style within Geometric Greece. Indeed, as we shall also see in later centuries, there are strong regional styles within each period of Greek art even when producing the same type of object or using the same materials and techniques. Given its consistent production during this period, then, we will look at the pottery of these four centuries before turning to sculpture and architecture.

pottery

Excavations at the Kerameikos and Agora areas of contemporary Athens have provided the most complete survey of developments in pottery from about 1085/80 все, when the sub-Mycenaean period begins, down through the Protogeometric and Geometric periods (see timeline for period subdivisions and dates). The area called the Kerameikos today was a prominent burial area on the northwest side of Athens, as well as the place where Athenian pottery was later made. Before the classical period, however, the area known today as the Agora was not yet the marketplace, but a mixture of residential, funerary, and workshop activity.

|

During the sub-Mycenaean period, we no longer see chamber tombs as in the Mycenaean era (see Figures 3.10 and 3.11, pages 61, 62), but instead find bodies placed in a trench or pit (known as a fossa tomb), sometimes with slabs surrounding it to make a cist grave. Frequently vases such as amphorae, drinking cups, and oil containers (either a stirrup jar or a new shape called the lekythos) were left in the grave for the dead. Taking a look at one of these vessels, an amphoriskos (Figure 4.1), offers a strong contrast with the vases of even the latest Mycenaean era, such as the Late Helladic (LH) IIIC octopus stirrup jar seen in the last chapter (see Figure 3.15, page 65). The clay surface of this sub-Mycenaean amphoriskos is not as smooth and even in texture as the octopus stirrup jar; the shape is thicker and the edges less sharp, as can be seen at the transitions between the parts of the vessel like the join of the neck to the shoulders. The painted decoration is not only far simpler, but the lines are more uneven and inconsistent in their application. The even, thick quality of the paint on the octopus stirrup jar, its more symmetrical composition, and its detailed drawing took considerably longer to do, and required a greater application of skill than is apparent in the sub-Mycenaean vessel. This pot is functional, but not much more than that, and bears witness to a decline in the resources that society was willing to invest in pottery at that time.

The sub-Mycenaean period lasted to the middle of the eleventh century, at which time we can begin to see some changes in both the style of the pottery and its context. The placement of graves in

The sub-Mycenaean period lasted to the middle of the eleventh century, at which time we can begin to see some changes in both the style of the pottery and its context. The placement of graves in

the Kerameikos was moved further away to the northwest in an area that was used continuously as a cemetery into the eighth century and later. Rather than inhumation, there was a change to cremation burial, with the ashes placed in a large amphora (Figure 4.2). This was set into a pit along with other vessels for the dead, and the tombs were then covered, as before, by a small mound of dirt and sometimes stone. Changes in burial custom, from inhumation to cremation and from group burials to individual tombs, are significant as they must reflect changes in social or religious attitudes. Cremation burials occur elsewhere in Greece at this time in places like Lefkandi and Argos, but are used alongside inhumation burials. The coincidence of these changes with an increase in the quality of pottery and grave goods may reflect new attitudes about social status or structure. In the Iliad, cremation is the only form of burial and the ritual and offerings associated with the burials of Patroklos and Hektor make it a heroic form of burial. Perhaps the changes in burial customs reflect a desire to emphasize the status of the deceased and family within the civic burial ground.

the Kerameikos was moved further away to the northwest in an area that was used continuously as a cemetery into the eighth century and later. Rather than inhumation, there was a change to cremation burial, with the ashes placed in a large amphora (Figure 4.2). This was set into a pit along with other vessels for the dead, and the tombs were then covered, as before, by a small mound of dirt and sometimes stone. Changes in burial custom, from inhumation to cremation and from group burials to individual tombs, are significant as they must reflect changes in social or religious attitudes. Cremation burials occur elsewhere in Greece at this time in places like Lefkandi and Argos, but are used alongside inhumation burials. The coincidence of these changes with an increase in the quality of pottery and grave goods may reflect new attitudes about social status or structure. In the Iliad, cremation is the only form of burial and the ritual and offerings associated with the burials of Patroklos and Hektor make it a heroic form of burial. Perhaps the changes in burial customs reflect a desire to emphasize the status of the deceased and family within the civic burial ground.

A distinct change of style in the pottery coincides with the change of burial practice. The fabric of the clay is now more refined and the paint is more evenly and thickly applied to the surface. The neck is more sharply articulated from the shoulders and the proportions are more vertical than the earlier amphoriskos. The handles are placed at the widest part of the body of the vessel and their ends are flattened to make a more gradual transition into the body. The shoulder is set off as a decorative field by the thick bands of dark paint below and above on the neck. While the wavy lines are a motif that continues from sub-Mycenaean times, two new decorative motifs appear. On the shoulder, facing upward toward the viewer, is a series of concentric half-circles. These were not made free-hand but with a multiple-point compass that gives them a precise and even appearance. This use of regular

geometric forms for decoration has given to the entire period the name “Geometric” and to the earliest pottery the label “Protogeometric,” first or beginning geometric.

This geometric approach to decoration can also be seen in the small horse that appears near the left handle. Indeed, this is among the first animal forms found in Greek art since the end of the Mycenaean period more than a century earlier. The neck and body of the horse have been formed like the arcs of a circle, very abstract but very recognizable and precise in their drawing. This horse is not a casual sketch, and the size, quality, and decorative motifs of the amphora show a greater willingness to invest in the visual appeal of a pot by both potter and patron, particularly considering that once seen during the funerary ritual and then buried, it would no longer be visible.

The number and value of grave goods in Athens increase over time, as a glance at the contents of a tomb from the north side of Areopagos Hill just to the west of the Acropolis demonstrates. This tomb, part of the Agora excavations, dates to about 900, at the beginning of the Early Geometric period (c. 900-850). Like the Protogeometric amphora, this is also a cinerary urn, which contained the remains of a male in his mid-thirties (Figure 4.3). An iron sword has been bent around the neck of the amphora. In addition, the grave goods included two pitchers, three cups, a pyxis (lidded container), carbonized figs and grapes, and various iron implements, including bits for a horse, an axe, a chisel, two knives, and two spearheads (Blegen 1952).

The number and value of grave goods in Athens increase over time, as a glance at the contents of a tomb from the north side of Areopagos Hill just to the west of the Acropolis demonstrates. This tomb, part of the Agora excavations, dates to about 900, at the beginning of the Early Geometric period (c. 900-850). Like the Protogeometric amphora, this is also a cinerary urn, which contained the remains of a male in his mid-thirties (Figure 4.3). An iron sword has been bent around the neck of the amphora. In addition, the grave goods included two pitchers, three cups, a pyxis (lidded container), carbonized figs and grapes, and various iron implements, including bits for a horse, an axe, a chisel, two knives, and two spearheads (Blegen 1952).

The placement of weapons in the tomb signifies the importance of individual arms to a warrior, as the struggles over the armor of a dead hero such as Patroklos or Hektor in the Iliad attest. Bending the sword renders it useless except to the deceased, making it his permanently. There were also two iron bits for a horse among the grave goods, perhaps identifying the deceased as a member of the elite who could afford to own a horse and possibly serve in a cavalry unit. In this light, we can consider that the earlier Protogeometric horse, in view of its rarity and newness as a motif, could also have signaled elite status for the deceased whose ashes were inside the amphora.

The handles of the Early Geometric amphora are located at the neck and project outward, in contrast to the handles on the belly of the Protogeometric amphora. This is not just a stylistic distinction, but also a signifier of the gender of the deceased. Handles on the belly or shoulders of a vase are found with female graves, whereas a neck-handled amphora like this example is found with male tombs. Stylistically, the amphora is proportionally taller than Protogeometric amphorae, a trend that would continue throughout the Geometric period. Finally, the decorative scheme of the amphora also changes in the Early Geometric period. Most of the vessel is now painted dark, setting off the reserved decorative bands on the neck and belly. The latter features a tooth pattern with hatching framed by three lines. The neck has a meander or key pattern made up of a hatched- pattern line that moves at 90° turns from upper left to lower right; a smaller frieze of zig-zags above and below creates a complex frame for the major pattern.

Another nearby grave in the Agora excavations was for a woman, as can be seen in the different shape and handle placement for the cinerary amphora (see Figure 13.5, page 326). We will consider this distinction of gender more fully in Chapter 13, but for now one can note that whereas the goods of the

| |||

| |||

first grave are associated with warfare, the goods in the so-called “Boots Grave” include more pyxides, some earrings, and two sets of terracotta shoes. Shoes are sometimes included in grave goods as part of a “maiden’s kit,” representing objects given up with the transition from childhood to adulthood; here they may symbolize the marriage that death cut short (Langdon 2008, 136-137). Susan Langdon further suggests that the inclusion of two pairs of boots may relate to the cult of Demeter and Persephone, who are also important deities for marriage. While the shoulder-handled amphora marks the grave as belonging to a woman rather than a man, its decorative style is similar to the amphora in Figure 4.3, dating them to about the same time, around 900 все. Both amphorae share the emphasis

on the dark surfaces framing similarly placed decorative motifs; the meander pattern goes continuously around the neck since the handles do not interrupt the decorative zone.

In the succeeding Middle Geometric period (c. 850-760), there is an increase in the decorative complexity and vertical proportions of pottery. The tomb of the “Rich Lady” from the Agora dates to the beginning of the Middle Geometric period (MG I, c. 850-800), but surpasses many contemporary tombs for the wealth and unusual qualities of its grave goods. The cinerary amphora is large (72 cm) and was placed in a pit dug through one side of the trench used to cremate the body (Figure 4.4). The tomb was then filled and covered by a slab. Recent analysis of the bones found in the amphora not only confirmed that the deceased was a woman, but also found the bones of a fetus of seven or eight months in age, suggesting that the Rich Lady was pregnant when she died (Liston and Papadopoulos 2004).

|

The cinerary amphora is decorated with a complex ensemble of patterns and shapes. The primary decorative zone is now the belly rather than the neck, and two smaller decorative friezes break up the shoulder and foot of the amphora (Figure 4.5). Circles drawn with a multiple-point compass appear

| |||

| |||

twice on each side, framed by meanders and other patterns. The effect is like that of a complex carpet, and some scholars have wondered if the patterns of Geometric textiles, none of which have survived, might have been similar to those in pottery.

Stacked on top of the amphora in the grave pit was a terracotta chest with five pointed-bulb shapes that has been identified as a model granary and a small openwork terracotta basket that is a kalathos or wool basket, indicating the elite status of the deceased through agricultural landholdings. This high status is also suggested by the jewelry in the tomb, such as the faience-bead necklace with a glass pendant that probably came from Syria (Figure 4.6). The gold for the rings and earrings was also imported, but the simple engraving technique and angled or zig-zag patterns of the rings point to local manufacture. The earrings use two techniques that originate in the Near East at this time: filigree work, in which wires are twisted into shapes and soldered to the surface, and granulation, in which small beads of gold are soldered to the surface. The rectilinear style and patterns of the earrings, though, suggest either that they were made in Syria or Phoenicia for a Greek market by adapting the Geometric style, or that a Greek goldsmith had learned these foreign techniques to produce them locally with imported gold. In either case, the materials and craft are distinctive and must have demonstrated the wealth and connections of the deceased for the mourners gathered at the funeral. The inclusion of a partial stamp seal among the grave goods also suggests that the woman buried here may have overseen property and goods.

The second part of the Middle Geometric period (MG II, c. 800-760) saw a diminishment in metal grave goods, but there was a new development in the use of human figures for decoration on pottery, including scenes that can be described as having narrative action. On a small skyphos (cup) from Eleusis near Athens there are two scenes, one of a ship with helmsman and archer on it, and the other of a battle between two pairs of warriors fighting over a third pair of fallen warriors (see Figure 9.2, page 213). This scene, which we shall consider further in Chapter 9 on narrative in art, treats the human figure in a more rubbery fashion than the Protogeometric horse in Figure 4.2. The technique

can be described as both linear and silhouette, meaning that there is emphasis on the shape of the limbs, head, and torso but little anatomical detail, leaving only the action to be emphasized. These first figural scenes appear in association with graves, and we have to consider that their innovative subject matter, simple as it is, could distinguish the tomb of the deceased. The number of tombs with these visual markers is not representative of the entire community but of the land-owning elite who could afford, quite literally, to throw away their wealth on or in a grave to demonstrate their standing. Indeed, the association between elite tombs and stylistic developments of the period leads to the hypothesis that elite patrons worked with the potters/painters in Athens to develop increasingly distinctive forms of visual display that signified their status within the community (Whitley 1991, 181-183).

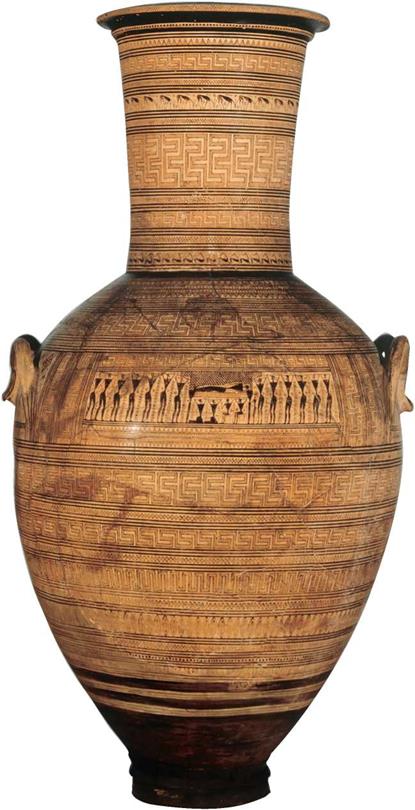

In the first decades of the Late Geometric period (LG I, c. 760-735) the use of painted pottery to distinguish the elite transforms the large burial amphora into a truly monumental grave marker. The so-called Dipylon amphora, attributed to an anonymous artist called the Dipylon Master and dated in the decade 760-750 (LG IA), takes its name from the cemetery found by the later Dipylon gate in the Kerameikos (Figure 4.7). At 1.55 meters (61 in) in height, it is a truly monumental work, one of two such amphorae that along with a couple dozen kraters come from the same area of the cemetery. These monumental vases created external visual markers of elite status that continued to be seen long after the funeral. The Dipylon amphora was made in three sections and joined, and its proportions are carefully controlled. The neck is half the height of the body, creating a 1:2 proportion, and the vase’s widest diameter is in this same proportion to its height, 1:2. The ornamental bands have now taken over the entire surface of the vase, with single, double, and triple meanders arranged in a varied and rhythmic pattern that frames the central figural scene placed between the handles.

In the first decades of the Late Geometric period (LG I, c. 760-735) the use of painted pottery to distinguish the elite transforms the large burial amphora into a truly monumental grave marker. The so-called Dipylon amphora, attributed to an anonymous artist called the Dipylon Master and dated in the decade 760-750 (LG IA), takes its name from the cemetery found by the later Dipylon gate in the Kerameikos (Figure 4.7). At 1.55 meters (61 in) in height, it is a truly monumental work, one of two such amphorae that along with a couple dozen kraters come from the same area of the cemetery. These monumental vases created external visual markers of elite status that continued to be seen long after the funeral. The Dipylon amphora was made in three sections and joined, and its proportions are carefully controlled. The neck is half the height of the body, creating a 1:2 proportion, and the vase’s widest diameter is in this same proportion to its height, 1:2. The ornamental bands have now taken over the entire surface of the vase, with single, double, and triple meanders arranged in a varied and rhythmic pattern that frames the central figural scene placed between the handles.

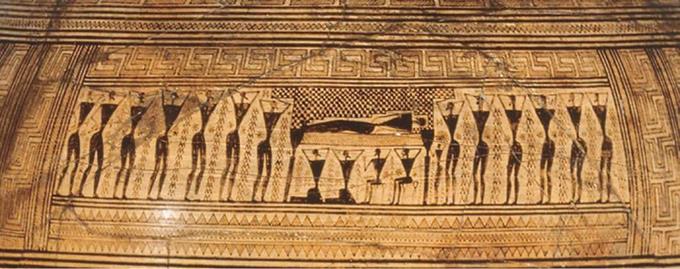

This picture shows a prothesis, or laying out of the body on a bier with mourners surrounding it (Figure 4.8). The figures, like the vase itself, follow a regular ratio of proportions. Taking the head as a single unit, the triangular torso is about two units in height, the upper legs and hips from the narrowest part of the waist a bit more than that, and the lower legs a bit less, with a head:body ratio of 1:7. The width of the shoulders is about the same as the height of the neck and head, and we can say of these figures that they live up to the label geometric. The checked area above the body is the burial shroud, but it is placed like a panel so that we can see the body that it covered. The mourners are spread out below and to the sides to be clearly visible, but were surrounding the bier in reality. This schematic approach very legibly presents all the elements that one might expect at an elite funeral. The hands of most of the mourners are placed on top of the head in a mourning gesture we know from later art as tearing at the hair in grief. Several figures raise up a hand, as if directing the funeral song or threnody, or making a prayer. There is no indication of the gender of these figures, neither breasts nor genitals, but the mourners are likely women and the deceased must be the woman whose grave was marked by the vase. The other side of the vase has a much simpler picture of eight mourners, so that we can call the prothesis the “front” of the vase that must have been directed toward the main point of access to the grave.

This picture shows a prothesis, or laying out of the body on a bier with mourners surrounding it (Figure 4.8). The figures, like the vase itself, follow a regular ratio of proportions. Taking the head as a single unit, the triangular torso is about two units in height, the upper legs and hips from the narrowest part of the waist a bit more than that, and the lower legs a bit less, with a head:body ratio of 1:7. The width of the shoulders is about the same as the height of the neck and head, and we can say of these figures that they live up to the label geometric. The checked area above the body is the burial shroud, but it is placed like a panel so that we can see the body that it covered. The mourners are spread out below and to the sides to be clearly visible, but were surrounding the bier in reality. This schematic approach very legibly presents all the elements that one might expect at an elite funeral. The hands of most of the mourners are placed on top of the head in a mourning gesture we know from later art as tearing at the hair in grief. Several figures raise up a hand, as if directing the funeral song or threnody, or making a prayer. There is no indication of the gender of these figures, neither breasts nor genitals, but the mourners are likely women and the deceased must be the woman whose grave was marked by the vase. The other side of the vase has a much simpler picture of eight mourners, so that we can call the prothesis the “front” of the vase that must have been directed toward the main point of access to the grave.

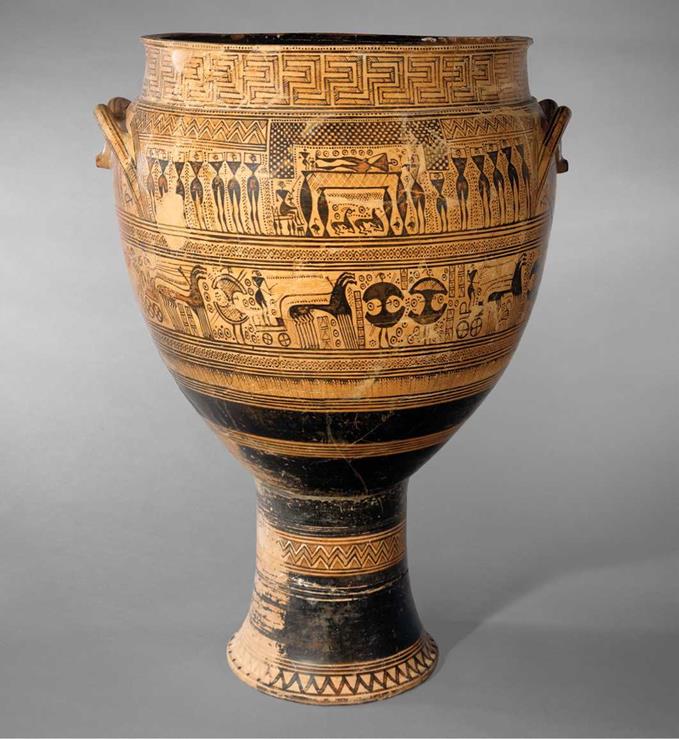

The workshop of the Dipylon Master continued to produce monumental grave markers into Late Geometric IB (c. 750-735), including a krater currently in New York that stood over the tomb of a man (Figure 4.9). The figural scenes here are more complex and tailored to expressing the gender and elite status of the deceased. A prothesis scene is placed again between the handles, and the posts of the bier serve to focus the viewer’s attention on the deceased. The mourners to either side of the bier now have two small projecting lines on their torsos to indicate breasts; the hair of these women is also pulled up and out as if they were tearing it. The head of the figure is now a circle with a dot in the middle; together with the projection that resembles a nose, these figures give a little more sense of being able to see as well as to act. Under the deceased are funerary offerings, and an elaborate, woven burial cloth is draped above the figure as it is prepared for burial. There are two half-size versions of the figures that can be seen with the adults, perhaps the children of the deceased? The changes in representing the figure here are relatively slight, but they create an opportunity to represent a more complex scene and a greater range of the participants’ identities.

|

4.7 Late Geometric IA Attic amphora from the Dipylon cemetery (Kerameikos) attributed to the Dipylon Master, c. 760-750 все. 5 ft 1 in (1.55 m). Prothesis. Athens, National Archaeological Museum 804. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Giannis Patrikianos) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund.

|

Below the prothesis is a second figural frieze with chariots carrying male charioteers, indicated by their plumed helmet crests. In between the chariots are walking warriors whose body is formed of a circular shield cut with notches in the side that has been called a “Dipylon” shield, after the cemetery where so many of these painted figures were found. Each warrior has two spears and a sword, recalling the grave goods from the Early Geometric warrior’s tomb above (Figure 4.3, page 73). The marching warriors and chariots are probably an honorific procession, perhaps circling the prothesis above as part of the funerary ritual. Funeral games were also part of the elaborate funerary rites for the elite, as can be read in the description of the funeral of Achilles’s companion Patroklos recounted in Iliad 23, and the chariots may also refer to that later celebratory event of the funeral.

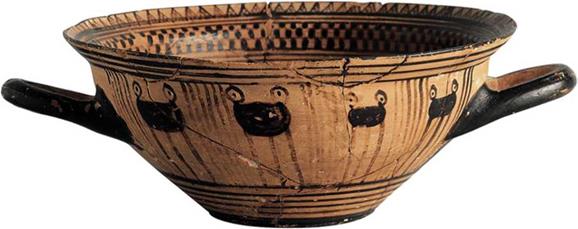

The fashion for monumental vases as elite grave markers does not continue beyond the middle third of the eighth century. During the Late Geometric II period we see other changes, including the return of inhumation burial in Athens and the use of vases as grave goods in a larger number of graves (see Figure 5.25, page 124). Figural scenes become more numerous in the later eighth century and appear on smaller objects, such as drinking cups, pitchers, and small amphorae. The skyphos in Figure 4.10 shows a row of tripods separated by groups of vertical lines on the exterior, looking like the later arrangements of triglyphs and metopes of the Doric order of architecture (see Chapter 7). On the inside of this cup we see processional lines of men wearing swords at their waists and women wearing long checked skirts. The addition of skirts helps to distinguish the gender of the figures more readily, but also creates a disparity between the nude and clothed figures. Some of the figures hold hands as they dance together, separated by figures bearing half-discs thought to be lyres. There are three groupings of men and women on the frieze, and it has been suggested that these are choruses competing against each other as part of a festival, with the tripods on the exterior to be awarded to the victors. The development of non-funerary subject matter on vases that are not exclusively grave goods, but could also have been used in a domestic or other context, reflects the development of a new civic identity during the late Geometric period, with the roles of men and women in the polis defined through ritual performance such as dances (see Langdon 2008).

Up to now we have been looking solely at Attic vases, but Geometric pottery was produced in many regions. Euboea, a large island off the eastern mainland to the north of Athens, was an important area in the Protogeometric period and maintained contact with the Mediterranean world through the Early Iron Age. We shall discuss later some architecture and sculpture from the Euboean

Up to now we have been looking solely at Attic vases, but Geometric pottery was produced in many regions. Euboea, a large island off the eastern mainland to the north of Athens, was an important area in the Protogeometric period and maintained contact with the Mediterranean world through the Early Iron Age. We shall discuss later some architecture and sculpture from the Euboean

|

4.9 Late Geometric IB Attic krater from Dipylon cemetery (Kerameikos), c. 750-735 все. 3 ft 65/s in (108.3 cm). Attributed to the Hirschfeld Workshop. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1914, 14.130.14. Prothesis and chariot procession. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

|

|

4.10 Late Geometric II Attic skyphos from the Kerameikos, c. 735-720 все. Diameter 619/б4 in (16 cm). Interior: musician with male and female chorus; exterior: tripods. Athens, National Archaeological Museum 874. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Giannis Patrikianos) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund.

|

4.11 Late Geometric Euboean lidded krater from Cyprus, c. 750-740 все. 3 ft 9lA in (114.9 cm). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cesnola Collection, purchased by subscription, 74.51.965. Stags flanking sacred tree. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

|

site of Lefkandi, but for now will turn to the production of Geometric vases during the middle of the eighth century. Contemporary with the monumental krater from the Dipylon cemetery is a large, lidded krater in the Metropolitan Museum (Figure 4.11). Both vases feature the spread of the decorative bands across the whole vase and share several motifs such as meanders, deer, and checked patterns, but the Euboean work is distinctive in its use of running spirals, more complex animal scenes, and a subdivision of friezes into metope panels. The central panel here shows two deer reaching up symmetrically around a thin tree while a young deer suckles. This type of symmetrical, inward-facing heraldic composition was very popular in Near Eastern art in Syria, Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia, where a variety of animals and deities flank a sacred tree (see Figure 6.8, page 138). The Euboean picture reflects an awareness of eastern motifs and a willingness to translate them into a Geometric style using familiar animals such as deer. On either side of the central metope are panels with a tethered horse and bird and above them a double axe, a motif that had been common in Minoan art, as on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus (see Figure 3.2, page 52) and could possibly reflect that tradition.

The evidence for eastern contact lies not only in the motifs and compositions of the decoration, but also in the fact that this vase was itself found in Kourion, Cyprus, and so is a Euboean export, a repackaging of eastern formulae for an eastern market. Mycenaean potters had exported large vases to Cyprus, as we saw in Chapter 3 (see Figure 3.13, page 64), and the resumption of exports to Cyprus reminds us that trade is an exchange of both goods and ideas. Phoenician material and Cypriote pottery have been found at the Euboean site of Eretria, and Euboean pottery has also been found at al-Mina in Syria. We have to consider that Greek artists borrowed, adapted, and exchanged visual ideas within the Mediterranean during the Geometric period.

Turning to the southern section of mainland Greece, the Peloponnesus, we also find the use of human figures on pottery coming from the Argive region, such as the fragment of a krater from Argos from the middle of the eighth century (Figure 4.12). While many of the Argive kraters with figural decoration are from graves, like those from Athens, their subject matter is based on religious ritual and horse-taming scenes rather than the funeral rites. In the main panel we see a figure holding reins and a prod over a horse. The multiple zig-zag lines below, the small dots, fish, and water bird combine

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 2401;

4.8 Detail of prothesis scene in Figure 4.7.

4.8 Detail of prothesis scene in Figure 4.7.