middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 1 страница

2.21 Vapheio cup, LM IB.

Athens, National Archaeological Museum 1759. 318 in (7.9 cm). Youth and bull. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (George Fafalis) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture and Sports/ Archaeological Receipts Fund.

Athens, National Archaeological Museum 1759. 318 in (7.9 cm). Youth and bull. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (George Fafalis) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture and Sports/ Archaeological Receipts Fund.

|

Among the grave goods are some unusual works whose origin is hard to identify. Several bronze dagger blades have scenes inlaid with gold, silver, and a sulfurous compound called niello, which takes on a lustrous black appearance (Figure 2.22). On the lion hunt blade, found in Grave IV of Circle A, we see four hunters facing a charging lion. Three of the hunters bear large shields and aim spears at the lion, while one figure crouches to shoot an arrow. A fifth hunter already is dead, his body slumped before his shield. Two other lions run away toward the tip of the blade, one looking back at the scene. The hunters have the same stylistic features as the bull handler on the Vapheio cup or the figures in the West House frescoes, but the lion hunt is not a scene found in the Minoan repertory. Furthermore, the figure 8-shaped shield of the hunters is found only in Mycenaean art. The emphasis on war-like actions is more common in Late Helladic art than in Late Minoan,

| |||

| |||

although it is found in the nearly contemporary frescoes at Thera. Niello and the inlay technique have their origins in Syria and the Levant, rather than Crete. Ultimately, the dagger is a hybrid, a combination of Helladic, Minoan, and Near Eastern elements. Whether the artist was Minoan or a Mycenaean who might have been trained by a Minoan, clearly the patron was using this dagger and the other grave goods to create an identity as an elite Mycenaean, a ruler of an area that had been, during the Middle Helladic period, fairly insignificant. Whether they had acquired their wealth through trade, piracy, or warfare, or a combination of those activities, the grave goods of the Mycenaean elite demonstrated their extensive network of contacts in the Mediterranean and beyond.

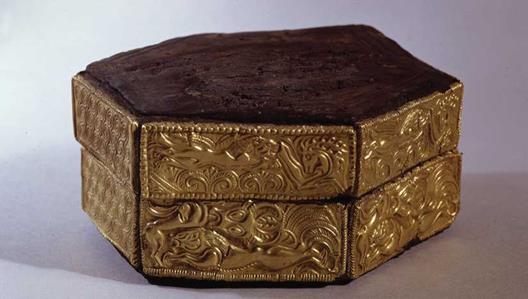

Other objects from the Shaft Graves show the eclectic tastes and agenda of the Mycenaean elite. A hexagonal wooden box from Grave V is covered with gold relief panels (Figure 2.23). The panels with running spirals are at home with other gold objects decorated with spirals in the graves, but the scenes of lions chasing deer are unusual. The chase is set in a lush landscape, with palm fronds, pal- mette shapes, and a lily-lotus hybrid flower below the lion in the top panel. The lions recall those on the hunt dagger in action, but are more schematic in style. The deer look very schematic and stylized in their contorted pose and sharply turned head. Although similar in technique to the Vapheio cup, the origin of this style is harder to place, and seems more at home in the Near East than in Crete or Greece. Perhaps this work too is a hybrid, and it certainly foretells in hindsight the greater involvement of mainland Greece in the Mediterranean world in the later Bronze Age that we will discuss in the next chapter.

As we have seen in this chapter, the Middle Bronze Age sees the development of elite, palatial cultures from the smaller-scale culture of the Early Bronze Age. These elites controlled sufficient resources to develop the architecture of the palaces, which, beyond providing a visual expression of their power, also served as their industrial, administrative, and religious centers. There was an emphasis in art on valuable and imported materials, and in some cases interesting or unusual subject matter or styles that would also serve to distinguish the palatial cultures visually. The Minoans could be said to be the dominant culture of the Middle Bronze Age, but the Mycenaean tombs show the emergence of a potential rival that will, in the Late Bronze period, dominate the Aegean, including the political control of Crete, as we shall see in the next chapter.

|

the late bronze age ii-iii

(C. 1600-1075 bce)

late minoan (lm ii to lm iii)

We will begin by looking at Minoan pottery of the LM II period that is labeled the Palace Style, recognizing Knossos as the dominant center of production. The LM II amphora from Knossos with an octopus (Figure 3.1) continues a decorative theme found in the Marine Style of the preceding period, LM IB (see Figure 2.17, page 39), but there are some significant changes that show a new sensibility in design. In profile, the vase can be considered top-heavy, with the widest section at the shoulder of the vessel, about three-quarters of the vessel’s height.

We will begin by looking at Minoan pottery of the LM II period that is labeled the Palace Style, recognizing Knossos as the dominant center of production. The LM II amphora from Knossos with an octopus (Figure 3.1) continues a decorative theme found in the Marine Style of the preceding period, LM IB (see Figure 2.17, page 39), but there are some significant changes that show a new sensibility in design. In profile, the vase can be considered top-heavy, with the widest section at the shoulder of the vessel, about three-quarters of the vessel’s height.

Combined with the narrow foot and wide mouth, this is a different approach to proportions when compared with earlier Minoan pottery, even in those vessels that had highly stylized spouts or handles and tall proportions (see Figure 2.9, page 32). The painted octopus fills up the central decorative panel, but in a different way from the Palaikastro octopus. The Knossos octopus is bilaterally symmetrical along a vertical axis in the arrangement and configuration of its body and tentacles. When compared to the Palaikastro octopus, the design is more formal, abstract, and rigid in concept; the idea of a rocky and undulating seascape as habitat is missing. The variation in the size and undulating curves of the arms and the thin coils at the end still give the design some sense of movement, but it has lost the naturalism of the Palaikastro octopus (and sprouted an extra pair of arms) and the asymmetrical composition. As we shall see, this increased abstraction and compartmentali- zation of the design elements are a feature of late Mycenaean pottery, and we can see the Knossos octopus as being influenced by Mycenaean art and perhaps patronage at the palace.

Indeed, in looking at pottery during this period we can see that Mycenaean pottery had a stylistic influence on Minoan pottery, reversing the cultural relationship found at the time of the Shaft Graves in Mycenae. In this chapter we will begin by looking at a few examples of Late Minoan art before turning our attention to the architecture and art of the Late Helladic period.

|

Frescoes continued to be painted at Knossos until LM IIIA, including the famous bull leaper’s fresco. Elite burials also continued, and a tholos tomb at Hagia Triada included a well-preserved stone sarcophagus that was covered in plaster and then painted like a fresco (Figure 3.2). The subject matter is ritualistic, but enigmatic. On the right we can see a tomb with ornate painted door and a wrapped male figure in front of it, presumably the deceased. Three men in kilts bring offerings of animals and an unidentifiable long object. To the left are two women and a male musician who are processing in the other direction toward an altar. There is a krater on top of it and it is flanked by a pair of standing double axes, a common ritual motif for Minoan art. The lead woman pours an offering into the krater and appears to be dressed like a Minoan priestess; the woman behind her carries two more vessels on a pole over her shoulder. We are not sure if the ritual is connected with the deceased in the other part of the picture, or perhaps shows other members of the deceased’s family carrying out an elite public ritual.

The figures are recognizably Minoan in some ways, including details of the hairstyle, poses, narrow waists, and costumes. The figures are drawn with heavy outlines and are more schematic in their anatomy and stiff in their postures than earlier paintings. The awkwardness of the priestess’s arms shows the difficulty or disinterest in rendering animated, three-dimensional figures compared to earlier Neopalatial representations like the Harvester vase or even the miniature Isopata seal ring (see Figures 2.15 and 2.16, pages 38, 39). Certainly the style shares features with Mycenaean fresco and pottery painting during this period, as we shall see later in this chapter, and it is possible that Mycenaean patronage and rule in Crete played a role in the development of LM III style.

late helladic architecture

As the Linear B tablets recount, the Mycenaean palaces were administrative centers that collected and distributed commodities and goods produced in their territory. The palaces included storage areas, as well as workshops for the production of pottery and more luxurious goods for the elite, and

areas for ritual and feasting. Minoan palaces served most of these same functions, but Mycenaean palatial architecture is different in the most important architectural features and their organization. As we shall see, the palaces were impressive both in creating effective housing for the political and economic administration of the kingdom and for projecting an image of kingly power.

Whereas the open courtyard was the main organizational feature of the Minoan palace, the Mycenaean palace centered around the megaron, a rectangular structure in the center of the palace. One of the best preserved of these is the megaron at Pylos, the so-called Palace of Nestor, one of the elder kings of Homer’s Iliad (Figure 3.3). The main room of the megaron was slightly rectangular and had a single doorway on the long axis. In the middle of the room was a circular hearth. To one side (left in the picture) was a throne for the king or wanax, as he was called in the Linear B tablets. Four columns, originally made of wood, flanked the hearth and supported a second floor and clerestory, as can be seen in the reconstruction drawing by Piet de Jong (Figure 3.4). The lower section of the walls was made of ashlar blocks of stone and the upper stories a mixture of materials, including rubble, timber, and plaster, which was painted with tempera or dry frescoes. The columns tapered upward and had bulbous capitals, like Minoan columns (see Figure 2.12, page 35). The fresco on the throne wall features lions and griffins, who symmetrically flank and guard the throne in a heraldic composition. Such compositions can be seen as an apotropaic device, protecting the room or doorway that they guard, but they are also an expression of kingly power, particularly in a large- scale and colorful composition. They draw the viewer’s eye to the wanax and his throne. We have already seen the association of lions and griffins with the elite burials of the Shaft Graves (see Figures 2.22 and 2.23, pages 44, 45), and this is a theme that continues in the later Mycenaean palaces and their art. Both motifs and the heraldic composition have origins in Near Eastern art, and their use at a monumental scale in the palaces provided a stage for the king that set him apart from the ordinary.

As can be seen in the plan of the palace (Figure 3.5), the main chamber of the megaron (4) was preceded by a small vestibule (3) and then a porch (2) that opened into a small courtyard (1).

3.3  Palace of Nestor at Pylos: view of megaron, LH IIIB. After C. W. Blegen and M. Rawson, The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia I: The Buildings and their Contents (University of Cincinnati and Princeton, 1966), Vol.

Palace of Nestor at Pylos: view of megaron, LH IIIB. After C. W. Blegen and M. Rawson, The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia I: The Buildings and their Contents (University of Cincinnati and Princeton, 1966), Vol.

1, Pl. 22. Image courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

3.4Reconstruction of the megaron interior at Pylos by Piet de Jong, LH IIIB. Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

3.5Palace of Nestor at Pylos: plan, LH IIIB.

After C. W. Blegen and M. Rawson, The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia I: The Buildings and their Contents (University of Cincinnati and Princeton, 1966), Vol. 1, Pl. 416. Image courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

After C. W. Blegen and M. Rawson, The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia I: The Buildings and their Contents (University of Cincinnati and Princeton, 1966), Vol. 1, Pl. 416. Image courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

Surrounding the megaron was a series of halls and smaller rooms that included storage areas. The bases for the large terracotta jars of olive oil in the room directly behind the megaron (6) can still be seen today; a wine magazine lay in a separate building just to the north (7). The archive, containing a deposit of clay Linear B tablets, lay next to the gate entering the palace court (5). The tablets, which were burnt and fired hard in the destruction of the palace, survived in great numbers at Pylos, adding to the larger cache of surviving tablets at Knossos. The tablets track the flow of commodities and storage at the palace, the circulation of materials, and the manufacture of products in the workshops of the palace. In this sense, the Mycenaean palace, like the Minoan palaces, functioned both for storage and for artisan workshops, and these would be located in the peripheral sections of the palace surrounding the megaron core. The tablets also document that the king and elite were important participants in ritual practices and provided wine and food, including meat, for feasts that took place in the palace.

The outer buildings are less clear in their function and probably had multiple roles. The northeast building (8) contained a shrine and perhaps workshops, while the southwest building (9) also had a smaller megaron set at a 90° angle to the axis of the main megaron. Other palaces also had smaller megarons, which have sometimes been called the queen’s megaron. It has been proposed that a second high official mentioned in the Linear B tablets, the lawagetas or “leader of the people,” perhaps a war leader, might have held office here.

The outer buildings are less clear in their function and probably had multiple roles. The northeast building (8) contained a shrine and perhaps workshops, while the southwest building (9) also had a smaller megaron set at a 90° angle to the axis of the main megaron. Other palaces also had smaller megarons, which have sometimes been called the queen’s megaron. It has been proposed that a second high official mentioned in the Linear B tablets, the lawagetas or “leader of the people,” perhaps a war leader, might have held office here.

The palace at Pylos was placed on a ridge overlooking a bay. The site had been used since at least the MH period but had been built up extensively by LH II, with several buildings using ashlar masonry facades under the influence of contemporary Minoan palaces. These buildings burned near the beginning of LH III, around 1400 все, and were then rebuilt in the plans seen above. The entire site was violently burned around 1180 at the end of LH IIIB and never built up again, marking the start of the collapse of Mycenaean culture during the LH IIIC period and leading eventually to the so-called Dark Ages that we will discuss more fully in Chapter 4.

The Linear B tablets provide some insight into the organization of artistic production in the palaces and outside of them. Four different potters are mentioned in the tablets, with one of them named as pi-ri-ta-wo and described as royal (wa-na-ka-te-ro, compare to wa-nax), meaning that he produced for the palace and received a landholding as part of his office (Hruby 2013). Of the pottery excavated at Pylos, about half was undecorated fine ware that belongs to the same hand or workshop, and is likely to be associated with the court potter. Another potter also seems to have worked as a smith for the palace. Finally, there are two other potters from a place named re-ka-ta-ne who appear on a list of craftsmen. These potters may have been independent artists who produced pottery on occasion for the palace, perhaps for special needs or as tribute or taxes to the palace from their production. Curiously, as Hruby points out, the quality of the pottery produced by the palace potter, including a large number of cups, is not very high. Late Helladic pottery can be of high quality, as we shall see later, and more work needs to be done to understand the mechanisms of production and markets in the Late Bronze Age. Recent research and analysis suggest that there were forms of markets outside of the palaces where pottery and other goods could be traded or acquired for use outside of the palaces.

Estimates of the population at Pylos put it around 3,000 inhabitants, while the larger and more fortified citadel and palace of Mycenae had about 6,000. Like the other palaces, the core of Mycenae was its megaron, set on the top of a prominent hill. The terrain is more difficult than at Pylos, and the shaft grave circles mentioned in Chapter 2 were lower down near the entrance to the citadel. Mycenae expanded during LH IIB and at the beginning of LH IIIB construction began on huge fortification walls to protect the palace. The walls were expanded outward to the south and west toward the end of LH IIIB when the famous Lion Gate was built (Figure 3.6). This expansion brought Grave Circle A with the shaft graves within the citadel, as well as some houses and a cult center. The fortification walls, about 5 meters thick, were made of massive, roughly shaped blocks

3.6 View of walls of Mycenae with Lion Gate, LH IIIB. Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

3.6 View of walls of Mycenae with Lion Gate, LH IIIB. Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

|

on the inside and outside and then filled with rubble between the faces of stone. Seeing these walls about 1,500 years later, Pausanias tells us that:

Parts of the fortification wall [of Mycenae], however, still remain, and also the gate, on which lions stand. They say that these are the works of the Cyclopes, who made the wall for Proitos in Tiryns ... There is a tomb of Atreus, and also the graves of those whom Aigisthos entertained and slew upon their return from Troy with Agamemnon ... Another tomb is that of Agamemnon, another that of Eurymedon the charioteer ... (Paus. 2.16.5-7; in Pollitt 1990, 11)

The stones of the walls, indeed, are huge in size, and are called Cyclopean after the legend of their building.

The stones of the walls, indeed, are huge in size, and are called Cyclopean after the legend of their building.

The Lion Gate is formed by a massive stone lintel set on two huge pillars, and the courses of stones above the lintel are corbeled to create a triangular space that relieves the weight on the opening. In this case, the builders used this as an opportunity to create an usual monumental stone relief to fill the triangle. In the center is a Minoan-style column set on two Minoan-style altars like that on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus. Two lion bodies in high relief face the column with their forelegs set on the altars. The heads of the lions were made separately and set by dowels on the bodies; these do not survive, but may have faced away from the column (see Blackwell 2014). The figures undoubtedly served as an apotropaic device, guarding the citadel; the symmetrical and inward-facing heraldic composition is common in Near Eastern art and architecture serving similar purposes, including the contemporary Hittite empire. The column would symbolize the megaron of the palace, and together with the altars would proclaim the political and religious authority of the wanax. It should be noted that the scale of the stone relief at Mycenae is unprecedented in Late Helladic art, and its size and sculptural quality would have been striking to a visitor approaching the gate, as it was to Pausanias even as a ruin centuries later. This unusual monumental display would create an impression of power and authority, and the soldiers watching traffic from the top of the walls on both sides of the passage would have confirmed that projection of power.

Equally impressive as architecture are the tholos tombs at Mycenae built in LH II and III. These replaced the shaft graves for elite burial and consisted of large circular chambers (the tholos) with a

|

|  |

|  |

|

long causeway (dromos) leading to their entrance (stomion). These were built into hillsides and then covered, creating an impression of beehives, as the tomb type is sometimes called. The masonry of the later tholoi is Cyclopean like the walls of the Lion Gate, and the best known example is the so-called Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae, built in LH IIIB (Figure 3.7). As the plan and section of the tomb show, the long dromos funnels the visitor to the massive doorway, which uses a lintel even larger than that of the Lion Gate and is estimated to weigh 100 tons or more. The dromos is over 30 meters in length and seems to lead into the earth as the walls rise higher on either side, although the ramp is actually sloped upward as the section drawing shows. The facade of the stomion originally had half columns and ornament set against the stones, and the emphasis on monumental entrance ways and long, narrow processional avenues is a recurring feature of Mycenaean architecture.

The space inside the tholos is unexpected for its height and volume (Figure 3.8). The interior vault is built through corbeling, so that the walls create a pointed arch profile that produces a stronger

The space inside the tholos is unexpected for its height and volume (Figure 3.8). The interior vault is built through corbeling, so that the walls create a pointed arch profile that produces a stronger

verticality. The top of the vault is 13.4 meters (almost 44 ft) in height, a truly remarkable achievement for a vaulted interior space. A side chamber with a small door and relieving triangle opens on the right side as one enters the tomb, and it is here, probably under the floor, that the deceased was buried. As the most impressive of the tholos tombs at Mycenae, it was named the Treasury of Atreus, the father of Agamemnon, but we have no evidence for who was actually buried in the structure since its contents were looted thousands of years ago. If multiple burials were made within the tomb, as was common in Mycenaean practice, the large central chamber would have been a clearly impressive stage for the secondary interment of Mycenae’s kings and members of the royal family at the height of its power and grandeur as a citadel.

verticality. The top of the vault is 13.4 meters (almost 44 ft) in height, a truly remarkable achievement for a vaulted interior space. A side chamber with a small door and relieving triangle opens on the right side as one enters the tomb, and it is here, probably under the floor, that the deceased was buried. As the most impressive of the tholos tombs at Mycenae, it was named the Treasury of Atreus, the father of Agamemnon, but we have no evidence for who was actually buried in the structure since its contents were looted thousands of years ago. If multiple burials were made within the tomb, as was common in Mycenaean practice, the large central chamber would have been a clearly impressive stage for the secondary interment of Mycenae’s kings and members of the royal family at the height of its power and grandeur as a citadel.

Like Pylos, the walls of the palace were painted with frescoes but survive only in small fragments. There were additionally frescoes found in one room of the cult center south of the Lion Gate and Grave Circle A. The complex housed four main shrines along with passages, storerooms, and workshops. The Room with the Fresco complex was built in LH IIIB and repaired after an earthquake before being destroyed by fire at the end of LH IIIB. In the room with frescoes was a bench, a hearth, and an altar in the corner. Above the altar on the wall were the remains of the bottom half of two dressed female figures facing each other, holding a sword and spear. They could be goddesses, being above the altar, but their identities are uncertain. In front of the altar and lower than the pair was a third figure, a woman holding sheaves of grain facing the altar (Figure 3.9). The frescoes were covered after the earthquake and the room apparently went out of use, but this helped to preserve some of the frescoes when fire finally destroyed the cult center.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1896;

2.22 Dagger from Shaft Grave at Mycenae, LH I. Length 87/i6 in (21.4 cm). Athens, National Archaeological Museum 394. Lion

hunt. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Giannis Patrikianos) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture

and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund.

2.22 Dagger from Shaft Grave at Mycenae, LH I. Length 87/i6 in (21.4 cm). Athens, National Archaeological Museum 394. Lion

hunt. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Giannis Patrikianos) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture

and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund.