Introduction and issues in the history of greek art

The first histories of Greek art were written in the Hellenistic period of the third to first centuries все, during the last priod covered in this book. By that time, Greek art and culture had spread well beyond the borders of the country of Greece today, and the Greeks themselves lived in cities from Russia and Afghanistan in the east to Spain in the west. Greek art was a common sight in Rome, whether statues expropriated from cities that the Romans had conquered or works commissioned from Greek artists by Roman patrons for their homes and villas.

The oldest extant account of the history of Greek art is a “mini-history” written by the Roman orator Cicero around 46 все and appearing in his history of rhetoric and orators entitled Brutus:

|

Who, of those who pay some attention to the lesser arts, does not appreciate the fact that the statues of Kanachos were more rigid than they ought to have been if they were to imitate reality? The statues of Kalamis are also hard, although they are softer than those of Kanachos. Even the statues of Myron had not yet been brought to a satisfactory representation of reality, although at that stage you would not hesitate to say that they were beautiful. Those of Polykleitos are still more beautiful; in fact, just about perfect, as they usually seem to me. A similar systematic development exists in painting. In the art of Zeuxis, Polygnotos, and Timanthes and the others who did not make use of more than four colors, we praise their forms and their draughtsmanship. But in the art of Aetion, Nikomachos, Protogenes, and Apelles, everything has come to a stage of perfection. (Cicero, Brutus 70; tr. Pollitt 1990, 223)

1.1 North frieze of the Parthenon, 442-438 все. 3 ft 5% in (1.06 m). London, British Museum. Cavalcade. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Brief though it is, this passage has the ingredients necessary for a history. Drawing from earlier Greek sources, Cicero names a series of artists in a chronological sequence, presenting us with a relative chronology of people and events, rather than an absolute chronology based on specific dates. He also tells us about the accomplishments of these artists. The first, Kanachos, created statues of the human figure in rigid postures, whereas his successors developed statues that were increasingly softer and more lifelike in appearance. This happened progressively over several generations, and Cicero singles out Polykleitos as nearly perfect in the way he sculpted the human form. We will see later a copy of a bronze statue called the Doryphoros or “Spear-Bearer” by Polykleitos (see Figure 10.7, page 243), but for now we can look at a similar figure from the Parthenon frieze that can be given an absolute date between 442 and 438 bce based on the inscribed accounts of building expenses for the Parthenon (Figure 1.1). The figure standing in front of the horse touching his head with his left arm stands in a very lifelike pose with the weight to one hip and leg. The muscles and anatomy of the body are articulated accurately and precisely, making him lifelike in appearance. Furthermore, he is a graceful, athletic figure whose nudity allows us to admire his beauty. We can see how Cicero might acclaim a Polykleitan statue of the mid-fifth century bce as both beautiful and “just about perfect.”

In his brief history, Cicero articulates an operating principle for Greek art, and in doing so makes his account more historical and interpretive than simply a chronicle of events and facts. He states, twice, that the purpose of art is to represent reality, and this becomes in turn a standard by which he judges the relative degree of success of the different artists. Not only do statues become more lifelike in their appearance, but they also become more beautiful, making a second criterion by which one can judge art and evaluate the achievements of different artists.

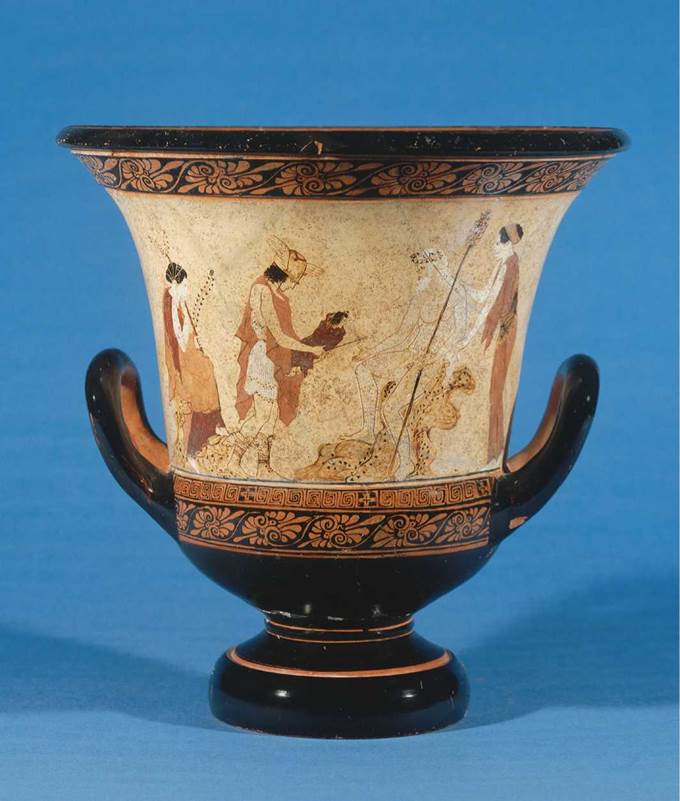

Cicero’s two principles, reality and beauty, are not exclusive to Greek sculpture, and are also the standard for his comments on the history of painting. In this even briefer passage, Cicero notes that painters underwent the same type of systematic development, from four-color work that relied on drawing, to presumably a full palette of colors with shading to make two-dimensional figures seem three-dimensional. What Cicero does not tell us directly, however, is that Apelles, the epitome of perfection for painting, was an artist who lived a century after the sculptor Polykleitos, so that the history of painting had a different absolute timetable than the history of sculpture. We have little surviving mural painting from this era, but we might look at a painting done on a ceramic vase about the same time as the Parthenon frieze (Figure 1.2). On the exterior of this vase, a mixing bowl or krater, we see Hermes bringing the infant Dionysos to Papasilenos for safekeeping from Hera, who was once again jealous over an illegitimate child fathered by Zeus. The figures are mostly in outline form with just a few added colors, and the effect is somewhat like the four colors of Polygnotos and Zeuxis mentioned by Cicero. There are some of the three-dimensional effects of perspective and shading, but on the whole, this painting would not seem to have met the standard of illusionistic “perfection” achieved by Apelles a hundred years later.

Cicero’s purpose was not to write a history of Greek art for its own sake, but to use it as an example of parallels to the development of oratory, which was of greater prestige than the “lesser arts” of painting and sculpture. We have to consider that this context filters the principles and protagonists of his history. In writing about oratory, Cicero claims that it reaches its perfection with Roman orators of the first century bce, surpassing earlier Greek rhetoricians. That Greek painting peaked later than sculpture makes the point that artistic development is not uniform and that oratory in contemporary Rome is just about perfect.

We further have to consider that the Latin terms used by Cicero might have meant something slightly different than the equivalent Greek terms would have meant in his sources. He uses the adjective verus and the noun veritas to describe the purpose of art, words that mean real and reality, as well as truthful and truth. In colloquial use, the meaning of the term with regard to art is “accurate representation of the natural appearance of a thing,” so that a work of art should look like a living

|

human being (Pollitt 1974, 138). Comparing the Parthenon frieze to an earlier work like the statues in Figure 8.9 (page 190), we can readily see that the Parthenon figure is more lifelike, more “real” or “true” in appearance. For Cicero as a Roman, however, there was also a tradition of lifelike individual portraits of citizens, frequently elderly men and women with deeply lined faces and receding hairlines. These portraits are also true, but they would hardly be described as beautiful like the Parthenon figure or the Doryphoros of Polykleitos.

Unlike today’s histories of Greek art, Cicero did not include any illustrations so that his readers could see what he was saying. Rather, Cicero assumes that his audience is already familiar with a number of these artists and with the general outlines of the history of style in Greek art. Indeed, the construct that Cicero presents of Greek art going from less lifelike (stiff) to very lifelike (real) in its representation of the human form, of the human figure being the most important subject of art in both Greece and Rome, and of Greek art of the fifth and fourth centuries все achieving a standard of beauty by which Roman or other art was measured, are themes that have dominated the modern histories of Greek art since the eighteenth century, when Johann Winkelmann published what is considered the first modern history of Greek art in 1764.

The modern vocabulary of art history, however, has changed. If one were to describe the Parthenon figure as “realistic” it would be misleading for a contemporary reader. The youthful male on the frieze is perfectly proportioned and graceful; he does not look like your average, everyday twenty-year-old. We would describe him as idealized rather than realistic. The Terme Boxer that we shall see near the end of the book (see Figure 14.22, page 367) is realistic in his representation: scarred, cut, and deformed as a result of the boxing contests he has fought. Both figures fit Cicero’s stated purpose of art as a representation of reality/truth, but a better modern art historical term for verus would be naturalistic, lifelike in appearance. Its opposite, the stiff figures of Kanachos, is best described by the term abstract, a simplified and schematic rendering of the human figure.

One might wonder, then, why there should be new histories of Greek art, since it was already an old and well-known story for Cicero. One reason is that Greek art was both familiar and contemporary for Cicero and his audience; it was still being produced when he lived and we have letters from him to Atticus, a friend and agent in Athens, with instructions and comments for purchases of Greek art to be shipped to Cicero’s villa in Tusculum, Italy. There the statues would adorn his library and what he called his “gymnasia,” colonnaded gardens modeled on the sites where Greek youth received physical and philosophical education. Cicero named his two gymnasia the Academy, where Plato had taught in Athens, and the Lyceum, where Aristotle taught. Indeed, Cicero had spent time studying philosophy in Athens as a young man and wanted to replicate the atmosphere of these places at his villa. Greek art was still alive in Cicero’s day, even if it had reached its peak much earlier, but for Cicero its purpose was decorative and personal, quite different from the public and purposeful role that Greek art played in its original setting.

Today, Greek art lives mostly in museums and is not part of the visual fabric of daily life, making it even more remote and foreign than it was to Cicero. Our terminology and cultural standards are different from Cicero’s and to learn about Greek art today requires much more remedial education about Greek life and culture. Another factor in approaching Greek art history again is that the questions of interest to art historians and archaeologists today have changed. Rather than looking for masterpieces of Greek art mentioned by Cicero and organizing collections by period, place, and subject matter, students of Greek art today are becoming more interested in the context of Greek art: who made something, who paid for it, what purpose did it serve, and what importance did it have in the lives of the ancient Greeks. We need to develop a history that can begin to address some of those questions.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1267;