Some questions to consider for this book

1.6 Terracotta group of women (Demeter and Persephone?), 2nd cent.

âñå. 8Ñå in (20.5 cm). London 1885,0316.1. Photo: © The Trustees of the Beyond style, the terracottas we have discussed have

British Museum. raised questions about the meaning of the figures and

how and why they ended up in a tomb or sanctuary. Even when we know that an artifact like the terracotta from Kamiros came from a tomb, we do not know

anything about the occupant of the tomb or the other artifacts found in it, as these details were not recorded as they were in the excavation of the Kerameikos tomb. The Tanagra terracotta highlights further the importance of provenance for the study of Greek art. This terracotta was purchased in 1885 by the British Museum from a collector, Charles Merlin, who had served as British Consul and later as agent and inspector of the Ionian Bank in Greece and who collected and sold hundreds of works to the museum. Most of these objects appear to have been chance finds, objects found by farmers or land

owners or perhaps amateur archaeologists and then put up for sale, but some were probably dug up by opportunistic excavators simply to make money. The difficulty is that the specific context and purpose for this object, whether grave good, religious offering, or domestic decoration, is lost. Even the origin of the piece can be obscured, as the style is similar to terracottas produced in Myrina in Asia Minor in the second century, but one cannot verify that attribution, made on the basis of stylistic analysis and comparison, through external evidence.

We will consider issues of collecting and cultural patrimony later in the textbox in Chapter 10, but the destruction of archaeological context through grave-robbing and looting from archaeological sites is particularly problematic. In these cases, provenance is either missing or even falsified in order to expedite the transportation and sale of a work; less valuable or more fragmentary objects are discarded and destroyed and restorations to make the prize pieces salable can change the original fabric of the work. As time goes on and contemporary populations grow and spread, there is less chance to find undisturbed ancient sites to provide us with information about the context, and systematic looting accelerates that problem.

We will consider issues of collecting and cultural patrimony later in the textbox in Chapter 10, but the destruction of archaeological context through grave-robbing and looting from archaeological sites is particularly problematic. In these cases, provenance is either missing or even falsified in order to expedite the transportation and sale of a work; less valuable or more fragmentary objects are discarded and destroyed and restorations to make the prize pieces salable can change the original fabric of the work. As time goes on and contemporary populations grow and spread, there is less chance to find undisturbed ancient sites to provide us with information about the context, and systematic looting accelerates that problem.

Even when there is an archaeological context for a work of art, one does not always know its origin and purpose. For example, a monumental bronze statue of a god was found in a shipwreck in the sea off Cape Artemision, on the north of the island of Euboea, in 1926-1928 (Figure 1.7). The statue, dated by style to the mid-fifth century, about 460 âñå, was found with another, second-century âñå sculpture of a horse and jockey. Both statues were being taken somewhere by ship, perhaps to Rome from Greece. This means that the original context for the statue is lost, even if its archaeological context is better known, and we can only speculate about its original identity and purpose.

The statue once held an implement in its right hand, meaning that we have no definitive attribute or other sign to identify the god. Most scholars today favor identifying the figure as Zeus with a thunderbolt, based on the shape and angle of the flange where the implement was once attached to the right hand.

Our ignorance of the original context, even when knowing the findspot, is of some importance in that the point of view for this work is critical for understanding how one might approach it. Entering its gallery in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens

today, one sees the view in Figure 1.7. From this vantage point, the articulation of the anatomy and the strong pose quickly convey the power of a god aiming a weapon. This is the vantage point found in most reproductions, as it provides the clearest possible view of the body and its naturalistic rendering of anatomy and movement, and creates a striking composition for a photograph.

The figure is so lifelike in appearance that it is not immediately apparent to a visitor that his arms are too long; if one were to rotate the left arm down toward the leg, the fingertips would touch the knee rather than the lower thigh as would be normal. The lengthening of the arm enhances the drama of the figure, but it also provides a clue as to how it might have been viewed originally. Such a bronze figure would have been an important dedication in a sanctuary or public area, and so we should think about the viewer approaching the work along a prescribed path. If one were to approach

the god from the front (Figure 1.8), one can see the god looking back. The weapon in the right arm would be aimed in the viewer’s direction, and the extended left hand would be sighting the target in the viewer’s direction too. From this vantage point, the lengthening of the arm adjusts for the foreshortened point of view and appears normally proportioned. This also changes the dynamics of viewing from the previous picture, in that the viewer is now also a target, a participant in the narrative action of the god. This view gives a dramatic vision of the power of a god and of the relationship between the human and divine missing in the other vantage point in Figure 1.7.

In other words, we need to consider not only the artist and patron/owner of a work of art, but also the viewer. We shall be discussing the Parthenon extensively in several chapters of this book, in part because of the lavish expenditure in its creation that made it one of the most refined and

In other words, we need to consider not only the artist and patron/owner of a work of art, but also the viewer. We shall be discussing the Parthenon extensively in several chapters of this book, in part because of the lavish expenditure in its creation that made it one of the most refined and

ornamented buildings in ancient Greece, and further due to its role as a symbol of Athens at its political and cultural height. In selecting a picture of the Acropolis for a book such as this, one usually sees views in which each of the buildings is as completely visible as possible. There is, however, one vantage point that brings them all together in a compact, stage-like view, as can be seen in Figure 1.9. In the center is the gateway to the Acropolis, the Propylaia, and just to its side the small Temple of Athena Nike (Victory). To the right and above is the west facade of the Parthenon, while to the left is the Erechtheion. The building to the left of the Propylaia obscures the view of the famous caryatid porch (see Figure 7.8, page 164), but contained the first Pinakothek, or painting museum. The buildings blend together, making the picture less suitable as an illustration to discuss their design, but what is significant about this view is that it is taken from the Pynx (see Figure 5.2, page 101). This open hillside to the west of the Acropolis is where the ekklesia, the assembly of Athenian voters, would meet to hear speeches and vote on proposals. Standing in the Pynx in the fifth century and later was the height of citizen participation in governance, and from here the claims of Athens to cultural and political leadership became manifest in the marble buildings on the Acropolis to the east. One can imagine the appeals of politicians to the citizens, as we will discuss in Chapter 10, to look upon this and be lovers of the city. The buildings of the Acropolis are spaced so that one can see some of them from almost any part of the ancient city, but it is from the Pynx that they all come together as one ensemble as Athenians carried out some of their most important civic duties.

The questions that will be of interest in this book, then, will consider meaning, context, viewer, and identity. For example, not only do we want to identify the figures and stories shown in Greek art, but we also want to consider how a story is being told. How does an artist show a narrative in a picture that might be different from the literary versions of tales that we know today? How might the meaning of a picture change when it is found in a sanctuary, a grave, or a house? How were the works of art meant to affect the viewers and frame a point of view or set of beliefs?

|

Some of these questions have to be answered based on the context, raising further questions that

we want to ask. Who made the work of art, where, and how? Was it made for direct sale, export, or

by commission? Who purchased it, and if it was transported to a new location from its place of origin, how did that happen and how did trade help to spread ideas, either to other groups of Greeks or to non-Greeks? What was the value of the art and what types of people would have owned it? How did a work of art get used in ritual, whether religious, civic, funerary, or domestic? Why might someone give or dedicate a work of art? How did a viewer interact with art long after the artist and owner had passed into history, and what value might the antiquity of a work have for the society?

In talking about people connected to the art, we also want to consider what it meant to them, recognizing that ancient society was not monolithic, but broken down in smaller, overlapping groups based on gender, age, ethnicity/language, socio-economic-political class, and geographical origin. How might a work of art like the Parthenon frieze or terracotta figures like those above have expressed the identity of the figures who made them, commissioned or owned them, or viewed them? Identity is complex, and made even more so by the long passages of time in Greek history, but the artifacts and images can tell us something about the people by and for whom Greek art was made.

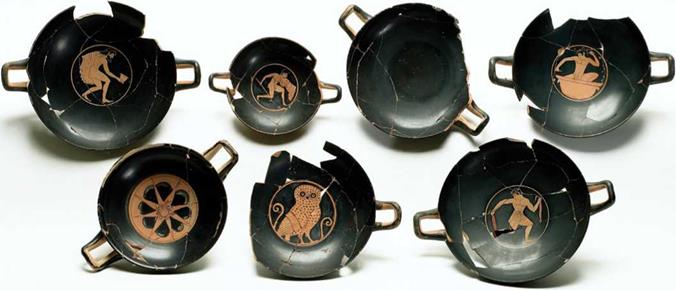

As an example, let us consider a collection of cups that was found in a well that was excavated in the Agora in Athens (Figure 1.10a). Stylistically, the cups, a shape called a kylix (pl. kylikes), are designated stylistically as red-figure ware since the surface of the clay was painted with a black slip, leaving the silhouette of the figure the red color of the iron-rich clay found in Athens. The one cup without figural decoration is covered with only the black slip, and is called black- glaze ware. Looking at the rendering of the figures, a date of 500-480 âñå has been suggested for the cups; the close similarity of the details of the cups and their figural painting suggests that they were obtained from the same or closely related workshops, perhaps in two batches (Lynch 2011).

The pot in the bottom left of Figure 1.10b is called a pelike and was used to hold liquid such as wine; stylistically, it is about a decade older than the kylix to the right that also appears in Figure 1.10a. The other three vessels are made in the black-figure technique, in which the silhouette of the figure is painted with black slip and the clay surface is left unpainted. The top right

|

1.10a Attic pottery from Well J2:4 in the Agora, Athens, c. 525-490 âñå. Diameter of top left without handles: 7%6 in (19.2 cm). Athens, Agora Museum. Top row: red-figure kylikes (P32420, P32411), black-glaze kylix (P32470); red-figure kylix (P32419). Bottom row: red-figure kylikes (P32421, P32422, P32417). Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

1.10b Attic p ottery from Well J2:4 in the Agora, Athens, c. 525-490 âñå. Height of top right: á3/à-á5/à in (16.2-16.9 cm). Athens, Agora Museum. Top row: black-figure amphoriskos (P32416); black-figure skyphos (P32413). Bottom row: red-figure pelike (P32418); red-figure kylix (P32417); black-figure oinochoe (P32415). Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

1.10b Attic p ottery from Well J2:4 in the Agora, Athens, c. 525-490 âñå. Height of top right: á3/à-á5/à in (16.2-16.9 cm). Athens, Agora Museum. Top row: black-figure amphoriskos (P32416); black-figure skyphos (P32413). Bottom row: red-figure pelike (P32418); red-figure kylix (P32417); black-figure oinochoe (P32415). Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

vessel is a cup type called a skyphos. Holding about 3.5 liters, it is a large version of the skyphos and is a little too big to serve easily as a drinking cup. It might have served as a mixing bowl for wine and water, as the Greeks customarily drank their wine diluted. The small vase on the top left next to the skyphos is a storage container called an amphoriskos (a small amphora), and might

have held liquid such as wine. At the bottom right is a pitcher called an oinochoe, which would be used for pouring wine into drinking cups like the kylikes. The black-figure technique is older than red-figure, and the skyphos and oinochoe are dated 525-500 âñå, perhaps two decades earlier than the cups. Here we have all of the pottery that we would need for a symposion, or formal drinking party that we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 5, but the small size of the amphoriskos and of the skyphos as a mixing bowl might have made them more suitable for more informal and everyday drinking, perhaps using some of the other smaller and plainer drinking cups found in the same well deposit.

What is of particular interest about this assemblage is that these vessels as well as many other pots were found as fill in a household well and were put there when household debris was cleared for reconstructing the house. The house itself was destroyed as part of the sack of Athens by the Persians in 480-479 âñå, giving us a terminus ante quem for the pottery. This means that some of the pottery, like the black-figure ware, was over a generation old and was still in use at the time the house was destroyed. The kylikes were not very recent purchases, but had likely been bought a decade before the destruction. Stylistically, the cups come from related workshops, so in a sense they make a “matched” household set, even if they are not identical to each other, but the suggestion that they were bought in two or three groups at different times and perhaps from different workshops means that the concept of a matched set, or even a set of drinking ware, did not mean stylistic unity or repetition of subject matter. The kylikes may have been used for household symposia, usually associated with feast days, but there were other sturdier drinking vessels that were used for everyday or private drinking, perhaps along with the black-figure vases in Figure 1.10B. Thinking of it in present-day terms, the red-figure cups would be like fine china used on holidays, while the other cups were perhaps less costly and used more frequently and less formally.

The subject matter is mostly universal in nature, with only the oinochoe showing mythological figures (Herakles with the Cretan bull and Athena, one of his twelve labors). The other subject matter is best termed Dionysiac since it relates to wine: dancers, drinkers, musicians. The recent excavation of this material and its analysis and publication by Kathleen Lynch offer a rare glimpse at a household assemblage and bring us closer to seeing how art functioned in a Greek household. The existence of different sets of cups for different occasions shows the importance of the symposion as an activity, for which a household would invest its resources in painted pottery, making it something of the mass media of its day.

the plan of this book

If one were to have visited a Greek site like the Acropolis in Athens or the sanctuaries of Delphi and Olympia back in ancient times, one would have had a synchronic picture of Greek art, that is, one in which buildings and artwork of vastly different periods and centuries would be set side by side, sharing the same space and possibly even the same function of housing dedications or performing rituals. The contrast between an archaic dedication and one from the Hellenistic period would have been readily apparent, but the diachronic narrative of how Greek art changed over time, such as the terracotta figures that we discussed earlier, would not be obvious. For this to happen, we would want to see all of the work from one century or period placed together, and those of other periods set in their own precincts.

A history of Greek art needs both types of narratives, but the pedagogical tradition is to follow primarily a chronological or diachronic scheme, starting at the beginning and going to the end of the first century âñå when Rome and its culture become the dominant civilization of the ancient Mediterranean. Rather than look at contextual issues as digressions from this diachronic history, this book will take a different approach, dividing the chapters into those that are mostly concerned with

specific periods or centuries and those that focus on contextual and other issues. This second group of chapters will be synchronic, mixing works from different periods to see both continuity and change in Greek society and culture. Each set of chapters will refer to issues and illustrations in the other group.

To begin, we will survey briefly the Early and Middle Bronze Age in Chapter 2 and the Later Bronze Age in Chapter 3. This era deserves a text in its own right, but the Bronze Age was the time remembered in the Iliad and literally lay under the feet of later Greeks, forming their own ancient history. Chapter 4 will look at the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age and the first development of the Greek polis or city-state (c. 1125-700 bce) and marks the start of the chronological series of chapters on Hellenic or Greek art. The next chapter, Chapter 5, however, will look at the context for Greek art: the city and civic life, the Greek house, and cemeteries, where Greek art and architecture served social and cultural roles from the Geometric period (900-700 bce) to the Hellenistic period (c. 330-30 bce). Chapter 6 will survey the seventh century bce, sometimes called the Orientalizing period, and Chapter 7 will explore the Greek sanctuary and temple, which first developed its basic configuration during the seventh century. Chapter 8 will look at the sixth and early fifth centuries bce, when many of the media and orders of Greek art were defined and refined. This is also the period when Greek art began depicting many mythological stories, and Chapter 9 will focus on visual narratives and storytelling in Greek art and how one approaches these pictures.

Chapters 10 and 12 look at classical art and architecture, focusing first on the fifth century bce and then the fourth century, the periods of the great artists named by Cicero, although virtually none of their works survives today. In Chapter 11 we will look at the economics of Greek art, its production and distribution, drawing upon information that becomes available during the classical period. Chapter 13 looks at issues of identity - gender, sexuality, ethnicity, geography, class - which become particularly important as the Greek world became more multicultural from the fourth century onward. Chapter 14 looks at the Hellenistic period, bringing us to 31 bce when Augustus defeated Antony and Cleopatra, the Ptolemaic Greek queen of Egypt, and Rome dominated the Greek and entire Mediterranean world for the next four centuries. The epilogue will consider aspects of the relationship between cultures, Greek and non-Greek, and why Greek art might still be of interest to us today.

The book is structured in such a way that one could go through the chronological chapters in order and then turn to the contextual chapters, or the reverse. Both sets of chapters have their own illustrations, but rely heavily on those from other chapters. Indeed, with a limit of just over 300 illustrations, one cannot fully illustrate every chapter independently, but I hope that turning backward or forward in the book to see an illustration (or clicking the link in an ebook edition) will help to emphasize the point that history is complex and both diachronic and synchronic at the same time. Some of the illustrations here will not be well known, and some well-known monuments, like the Delphi Charioteer to name one example, have not been included. This was necessary in keeping the balance and focus of the approach, and most of the well-known works are easily found today in scholarly resources on the web like the Beazley Archive or image databases like Artstor.

My hope is that in going to a museum or visiting a Greek site, the issues and themes raised in this book will help the present-day viewer to look at Greek art and architecture as the fabric of ancient Greek culture. Art can bridge the gaps between people created by time, language, geography, and culture; beginning to understand the complexities, contradictions, and ideals of another people, whether historical or contemporary, helps us to understand our own challenges.

a few notes about using this book

There are several ancient sources that are helpful in providing information and context for Greek art and architecture. The citation of ancient sources follows a standardized notation by author and/ or work, then book/chapter and section/paragraph/line, such as Herodotos 2.53, which would be Book 2, Chapter 53 of his History. This allows consulting different editions or translations whose

pagination will vary. The best compilation of these sources in translation is Pollitt 1990, and the most important sources used in this book are:

♦ Cicero, Brutus (cited as Cicero, Brutus). Roman orator and politician (106-44 âñå) and author of many letters and works, including Brutus, a treatise on rhetoric.

♦ Herodotos (cited as Herodotos). Greek historian (c. 480-420) who wrote a History, an account of the wars between the Greeks and Persians.

♦ Homer, Iliad (cited as II.) and Odyssey (cited as Od.). Late eighth-century poet attributed as author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, although some hold that these were by different authors.

♦ Pausanias (cited as Paus.). Greek doctor of the mid-second century ñå who wrote A Description of Greece, a travel guide in ten books.

♦ Pliny (the Elder), Naturalis Historia (cited as Pliny, N.H.). Roman encyclopedist (23-79 ñå) whose work, Natural History, has three chapters covering materials used in art and includes details on the history of Greek art.

♦ Plutarch, Vita Perikles (cited as Plutarch, Vita Perikles). Greek biographer and writer, c. 46-120 âñå. Author of the Lives, a series of biographies on notable Greek and Roman historical figures, including the life of Perikles (Vita Perikles).

♦ Thucydides (cited as Thuc.). Athenian historian (c. 460-400 âñå) who wrote a history of the Peloponnesian War.

♦ Vitruvius, de Architectura (cited as De Arch.). Roman architect active in the late first century âñå to early first century ñå and author of a treatise on architecture.

The textboxes in this book focus on issues that are currently debated in the field or introduce some recent methodological or theoretical approaches developed in the literature. These are intended to open discussion on the underlying issues about what we think we know, how we might know it, or what we ought to do about something.

There are many terms specific to Greek art or art history generally in this book. These have been defined in the text at their first use, but all have been collected into the glossary at the end. Each chapter has both bibliographic citations for references in the text and suggestions for further reading. The latter are not exhaustive, but are intended as starting points for more detailed exploration or information on the topics in the chapter. The captions also include museum inventory numbers, which allow for finding further information on the work in databases or publications. Finally, all dates are âñå unless otherwise noted.

|

.

the early and middle bronze ages

C 3100-1600 bce

chronology, regions, periods, and pottery analysis

Given the vast range of time covered by the Bronze Age and the lack of documented historical events and signposts, the discussion of Bronze Age art depends heavily on the sequence in which and places where the art has been found. The chronology of Bronze Age art has been constructed through the designation of periods and regions, as can be seen in the timeline for this chapter. As was mentioned briefly in the previous chapter, artifacts do not come with labels telling us when and where they were made and we need to place them in a sequence of periods and sub-periods in a relative chronology. Excavation determines the relative chronology of a site through stratigraphy, the layers of deposits and debris at a site, with the older material generally under the more recent material. Material that is sealed underneath a destruction layer of carbonized material could belong to a structure that was destroyed, while material on top would be more recent and belong to a rebuilding or reuse of the site. In order to calibrate the sequence of material across a site, or across an entire region, it is necessary to have comparanda. Presumably artifacts that are very similar in form and appearance belong to the same period and/or place, so that two deposits with similar artifacts should be contemporary and linked.

For the Bronze Age (and later), pottery is the key medium for determining the sequence of periods. Pottery was the all-purpose material of the ancient world, used for storage, cooking, drinking, shipping, and, in its finer forms, as gifts, dedications, or grave goods, so it appears in many different contexts. Once fired, it does not deteriorate like organic material. Once broken, it is often useless and so is discarded or used as fill. It may be traded or transported, but rarely is it looted in antiquity since it does not have the material value of metal or ivory. As it is constantly

|

needed, it is produced in batches that follow similar forms, function, and decoration at a particular time and place. Changes in technology, such as firing, glazes and slips, or the use of the wheel, will mean that pottery changes over time, and new shapes will arise in response to new needs or desires, but this type of change is relatively slow. Significant changes in pottery style generally take a generation or more to take hold, so being able to date a pottery sherd, then, will help to date a site or building and their phases of use.

To analyze pottery, one needs to consider several aspects of its physical and stylistic qualities (Rice 1987). The shape and components of a vessel are important features, and key diagnostic elements include the profile and details like the rims, handles, and the transition between the parts. The type of clay and its qualities, such as its refinement and coloring, are also distinctive. One also looks at the way a vessel is fashioned as another set of qualities, whether it is handmade or wheel-thrown, for example, or the thickness of its walls. The decorative techniques also aid in defining a style, such as incision, burnishing, or painting the surface with slips or glazes. In addition to the techniques of decoration, one can also examine the placement of the decoration and the motifs and compositions used. In the case of figural decoration on pottery, the features of the human anatomy and the representation of action help not only to distinguish the work of one region from another, but even to define the work of different artists.

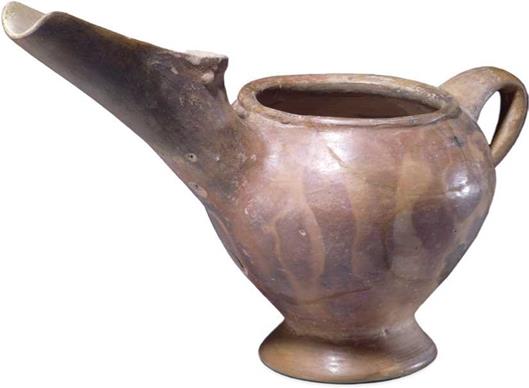

For example, the small pot in Figure 2.1 was found in the vicinity of Ierapetra on Crete. The main body of this vessel, usually called a “teapot," has a globular shape, with a loop handle on one side and an elongated spout opposite. The foot is conical in shape and the rim has a slightly raised lip. The handle tapers from flat and wide at the top to narrower and more cylindrical at its bottom, while the spout is nearly the same length as the body and projects upward at about a 40° angle. The parts blend together at their joints. The clay is generally smooth and refined, but shows some working by hand and the marks of tools. The vessel is handmade, rather than wheel-thrown, and the thickness of the clay is notable. In terms of its decoration, this teapot has slips of red and black applied to its surface in irregular shapes that have fired unevenly in the kiln, giving it a mottled effect. One finds similar patterns in stone that is used to make vessels, and perhaps the patterning

and color were meant to mimic stone. The surface has also been burnished to give it a smooth and polished look. Also distinctive of this ware are the the small knobs that appear near handles or on the spouts that look like rivets, and this similarity has led to suggestions that the pottery is imitating shapes in metalwork.

Works like this teapot are found at a number of sites in southern and eastern Crete, and the type is called Vasiliki Ware, after one of the first sites where it was excavated. A quick comparison to the nearly contemporary “sauceboats” found on the mainland at Lerna show some similarities (see Figure 2.5, page 28), but many more differences from Vasiliki Ware in Crete. The presence of the pottery in different sites in Crete allows one to place the levels where they are found, and the other objects with them, into the same time period and to construct a relative chronology across the region.

For the Bronze Age in Greece, archaeologists have constructed a relative chronology based on changes in pottery style, dividing Greece into three regions. As can be seen in the timeline, the area of the mainland is designated as Helladic, the Aegean islands as Cycladic, and Crete as Minoan, after the legendary King Minos. The chronology of each area is divided into sequential phases based on chronological sequence, starting with a tripartite division into Early-Middle-Late, followed by further subdivisions as necessary based on the archaeological record: I-II-III, A-B-C, 1-2-3, etc. Thus, the Early Bronze Age on Crete is labeled EM (Early Minoan) and divided into three periods (I, II, III) and two sub-periods (IIA and IIB). Thus, we have a sequence of EM I, EM IIA, EM IIB, and EM III, with Vasiliki Ware falling into EM IIB. The Early Cycladic chronology is similar, but without subperiods: EC I, EC II, EC III. For the mainland, the Early Helladic (EH) is similar to Crete in the sequence of periods: EH I, EH IIA, EH IIB, EH III. The movement of artifacts across the regions, such as discovering a Cycladic object like a frying pan at a mainland site, helps to correlate the different phases across the three regions.

The three-phase model was established early in the history of archaeology, but more recent work has developed alternative period schemes that correspond better to the archaeological material. For the Early Cycladic period, an alternative sequence of five “groups” has come into use, named after important sites. As can be seen in the timeline, these groups span EC into MC I but do not always fit well into the traditional EC I-II-III divisions. Of these five groups, the Keros-Syros Group is particularly noteworthy for the production of marble figures, while the Kastri Group in the same EC II period represents a different population that succeeded the Keros-Syros Group.

For Crete, an alternative to the tripartite division of EM, MM, and LM is a five-part sequence based on the establishment of large palaces as central administrative and artistic centers. Hence, archaeologists speak of the Prepalatial period (roughly EM I to MM IA), the Protopalatial (first palaces, MM IB-MM II), the Neopalatial (the new palaces, rebuilt following the widespread and nearly simultaneous destruction of the first palaces, MM III-LM IB), and the Final Palatial, when only one site, Knossos, continued to function after a second wave of destructions and then invasion from the mainland (LM II-LM IIIA). The Postpalatial follows until the end of the Bronze Age (LM IIIB-LM IIIC). The need to have smaller chronological groupings, however, means that both systems will sometimes be used in the same discussion.

Finding a terminus to establish an absolute chronology is difficult for the first millennium âñå, but even more so in the Bronze Age. As we will see throughout this book, finding an absolute date is rare and when one does, it becomes the anchor for the relative chronology established by excavation, analysis, and comparison of artifacts. For the Bronze Age, the external evidence was originally derived from other Mediterranean cultures, particularly Egypt. However, more recent evidence based on the eruption of Thera near the beginning of the Late Bronze Age has created an alternate terminus that does not correspond with the traditional chronology, leading to controversy over dates as we shall see.

The early phases of each region - EM, EC, EH - are generally dated between c. 3100 and 2000 âñå. These dates and those of the subdivisions are approximations working back from dates established for the Middle and Late Bronze periods, but have general confirmation from radiocarbon

testing. For the Middle Minoan period, dates were originally established by the discovery of pottery from Crete in Egypt. This pottery had been brought to Egypt most likely through trade, and was found in excavations of contexts belonging to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Since there were extensive king lists for Egypt going back from Roman times, the calendrical dates of the Egyptian dynasties provided potential termini for the Minoan pottery. Using this material, the period MM II was dated between 1900 and 1700 âñå. Such correlation with Egypt also resulted in a dating of the two waves of palace destruction, and the end of the Protopalatial and Neopalatial periods, to about 1750 and 1500 âñå respectively. This last destruction, the division between LM IA and LM IB, is also linked to the massive eruption of the volcanic island of Thera, which destroyed much of that island and sent tsunamis, ash, and destruction across the eastern Mediterranean. Recent scientific dating of the Thera eruption, however, places it between 1650 and 1600 âñå, not 1500 âñå, creating a discrepancy and controversy for dating the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (see Textbox, page 46). For our purposes, we will use the so-called “high” dating based on Thera, placing the beginning of the Late Minoan period at 1700 âñå rather than 1600 âñå in the traditional chronology.

This discussion of chronology, and especially of the difficulties in finding absolute dates for periods or monuments, highlights how much we have yet to learn about Greek art and archaeology. While the sequence of periods remains intact despite the controversy over the absolute dating of Thera, the development of alternative phases and nomenclature, such as Keros-Syros Group or Neopalatial, points out that history, society, and material culture are complex and resist fitting into neat schemes and boxes. Digging deeper will reveal both inconsistency and complexity, not just about chronology but about the cultures and artifacts that we study.

early cycladic and minoan

periods, C 3100-2000 bce

Humans have been living in Greece for millennia, and the archaeological remains of their early habitation in the Neolithic period, or new stone age, have been found in all of the three main regions. There was, at least in the late Neolithic, some knowledge of metals such as copper, pottery, and textiles, but the development of bronze marks a change in culture. Bronze, a combination of about 90 percent copper and 10 percent tin, requires greater technological expertise than working with copper and also requires a more complex social and economic organization since the source materials, especially tin, are not widely available and would need to be acquired through trade and communication. In the Near East and Egypt, where the Bronze Age began in the fourth millennium, this period corresponds to the rise of the great cities, monuments, and writing. The Early Bronze Age in Greece starts later and is more modest in scale.

The most well-known artworks from the early Bronze Age are the marble figures from the Cyclades (Figure 2.2). The earliest versions of these are simple, fiddle-shaped works with a flaring neck for the head, similar to the top rows of the figures found at the Chalandriani cemetery on the island of Syros. These are similar to figures found in Anatolia, suggesting a connection to that mainland culture. In the Keros-Syros Group of the EM II period, the figures develop into a more defined form of a nude, frontal woman with articulated arms, legs, breasts, genitals, and head. The bent arms are crossed over the abdomen in a form labeled the Folded-Arm Figure (FAF). The abdomen is generally rounded and only the nose is defined sculpturally; additional facial details were originally painted on the marble. The figures range in height from 10 cm to life-size, but most are under 40 cm. There is some variety in proportions and detailing by period and location, but some of the figures are similar enough to suggest that a workshop or artist was responsible

for producing a number of the works and some have been attributed to “masters” with titles like the Goulandris Master.

The Cycladic islands are rich in marble deposits, as well as obsidian and other stones used for cutting, which may help to explain the appearance of marble sculpture as a medium at this early time; marble statues will be rare after the Early Cycladic period until they begin to be produced in the seventh century (see Chapter 6). Most of the Early Cycladic settlements were very small; their cemeteries were located outside the habitation area and most of the burials were in individual, shallow cist graves. Most of the excavated FAF have been found in tombs, and it is possible that they were a means of showing the deceased’s prestige through the grave goods, which also included marble vases. Some FAF have also been found in the villages nearby, so it is not clear what their function was or what they represent. The abstract form and pristine lines and surfaces of the figures were much admired by artists and collectors in the early twentieth century, leading to many being dug up and put on the market without provenance. Additional forgeries further complicate the FAF record. In the absence of historical records and with limited examples from controlled excavations, the meaning and purpose of the works will remain speculative even as their aesthetic appeal continues to be strong.

The Cycladic islands are rich in marble deposits, as well as obsidian and other stones used for cutting, which may help to explain the appearance of marble sculpture as a medium at this early time; marble statues will be rare after the Early Cycladic period until they begin to be produced in the seventh century (see Chapter 6). Most of the Early Cycladic settlements were very small; their cemeteries were located outside the habitation area and most of the burials were in individual, shallow cist graves. Most of the excavated FAF have been found in tombs, and it is possible that they were a means of showing the deceased’s prestige through the grave goods, which also included marble vases. Some FAF have also been found in the villages nearby, so it is not clear what their function was or what they represent. The abstract form and pristine lines and surfaces of the figures were much admired by artists and collectors in the early twentieth century, leading to many being dug up and put on the market without provenance. Additional forgeries further complicate the FAF record. In the absence of historical records and with limited examples from controlled excavations, the meaning and purpose of the works will remain speculative even as their aesthetic appeal continues to be strong.

Also enigmatic are a class of terracotta objects called “frying pans” based on their shape, flat disks with flanges like short handles (Figure 2.3). The objects, however, show no signs of having been used for cooking. They have been found primarily in graves in the Cyclades, where presumably they had some funerary function or symbolism that remains unclear. Interestingly, examples of the frying pans have also been found on the Greek mainland, where they appear in domestic rather than funerary contexts. Their appearance outside of the Cyclades is an example of inter-regional contact and trade during the Early

Bronze Age, and also of the repurposing of an object

when it enters a new context. The frying pan would have had no practical purpose in an Early Helladic household, but its status as an imported good may have been appealing to its owner, as well as the different quality of its shape and decorative designs. EC pottery is found also on Crete, and its broader distribution in Greece suggests that the Cyclades may have been an influential culture during this period.

The decoration of the disks is made with incised lines or stamped designs pressed into the clay before firing. Some of the disks, such as this example from the Chalandriani cemetery on Syros, show simplified boats with lines for oars incised on both sides. The ships are not symmetrical

and have one much higher end, perhaps with steering oars. Surrounding the ship are concentric circles made by a stamp and then linked by lines to make the design look like running spirals. Perhaps, in conjunction with the ship and the small fish in the upper left, the pattern is meant to represent the sea, but the pattern also appears as a simple decorative scheme that fills up the entire surface on other pans without any reference to the sea or ships.

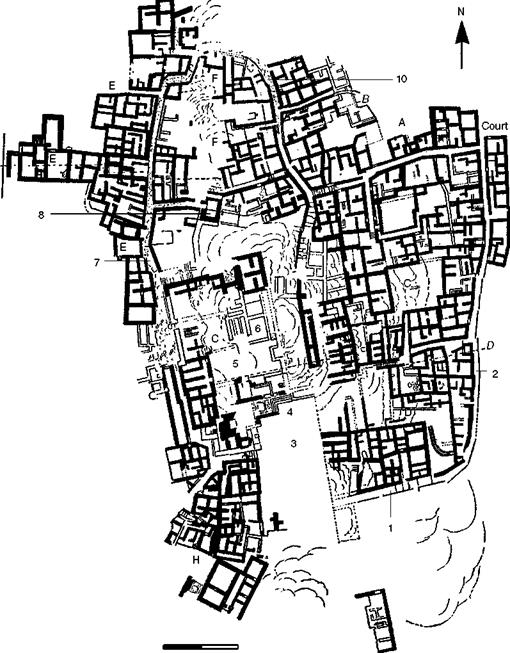

Early Cycladic villages consisted of houses made of mud brick and stone built on rough stone foundations and lower courses. A similar type of architecture appears on Crete, and the village of Myrtos is the best excavated example of an Early Minoan (EM) site (Figure 2.4). The site was first occupied in EM IIA (2700-2400 âñå) and was then expanded in EM IIB (2400-2200 âñå); it was destroyed at the end of EM II and the site was abandoned, probably by 2170-2150 âñå. The settlement was placed on the top of a hill, above the arable land, and consisted of a half-dozen houses set irregularly together, with lower stone courses surmounted by mud brick for walls and timbers and reeds for roofing. The oldest structure is in the center (in hatched lines), and the other houses were built incrementally during the second phase. Each of the houses had kitchen, storage, and living areas, with some rooms having benches that might have been used for storage or work surfaces. Clustering the houses together like this made them more secure and limited the number of entry points both to the village and to each dwelling. The spaces marked 13/14, 64/65, and 67 are passages and made navigating through the village like a maze. At some other sites, fortification walls surround the houses. As in the Cyclades, the cemetery was outside of the habitation. Unlike the Cyclades, Minoan tombs are communal rather than individual, with circular chambers being used for multiple burials.

Early Cycladic villages consisted of houses made of mud brick and stone built on rough stone foundations and lower courses. A similar type of architecture appears on Crete, and the village of Myrtos is the best excavated example of an Early Minoan (EM) site (Figure 2.4). The site was first occupied in EM IIA (2700-2400 âñå) and was then expanded in EM IIB (2400-2200 âñå); it was destroyed at the end of EM II and the site was abandoned, probably by 2170-2150 âñå. The settlement was placed on the top of a hill, above the arable land, and consisted of a half-dozen houses set irregularly together, with lower stone courses surmounted by mud brick for walls and timbers and reeds for roofing. The oldest structure is in the center (in hatched lines), and the other houses were built incrementally during the second phase. Each of the houses had kitchen, storage, and living areas, with some rooms having benches that might have been used for storage or work surfaces. Clustering the houses together like this made them more secure and limited the number of entry points both to the village and to each dwelling. The spaces marked 13/14, 64/65, and 67 are passages and made navigating through the village like a maze. At some other sites, fortification walls surround the houses. As in the Cyclades, the cemetery was outside of the habitation. Unlike the Cyclades, Minoan tombs are communal rather than individual, with circular chambers being used for multiple burials.

The village of Myrtos may have had only about fifty residents who were closely related to each other. Loom weights were found in several areas, showing weaving as one of the important activities of the settlement. Some of the spaces were specialized in their function. For example, 49 was a pottery production area, with vats of clay to be used for making pottery. Room 92 had a semicircular platform and eighteen vessels, as well as a terracotta female figure holding a jug in her arms. These features suggest that the room and its building were some type of shrine that served the community.

The pottery at Myrtos shows a change in style from dark lines on a light surface in EM IIA to a more burnished and mottled surface in EM IIB. As we saw earlier in this chapter, the new style is labeled Vasiliki Ware, after another site where it was found in large quantities. The teapot in Figure 2.1 (see page 22) is like examples found at Myrtos, with similarly elongated, asymmetric, or imbalanced elements and mottled surface patterns. The appearance of Vasiliki Ware at sites across Crete shows that even though the settlements were small, trade and communication spread new artistic ideas and practices across the region.

|

2.4 Plan of Myrtos, Crete, EM II. After P. Warren, Myrtos: An Early Bronze Age Settlement in Crete (London, 1972), insert. Reproduced with permission of the British School at Athens.

early to middle helladic

(C. 3100-1675 BCE)

Turning to the Early Helladic Greek mainland, we also see important developments in the middle of the third millennium in the period EH II. The archaeological evidence suggests that there were new peoples moving into the area at the end of EH I, and there is additional evidence of trade with the Cyclades in EC II/EH II, as mentioned earlier with the Cycladic frying pans. Among the most distinctive EH pottery products of this period are terracotta “sauceboats," like the examples found at the Peloponnesian site of Lerna (Figure 2.5). The earliest version of the shape (I in the drawing) is very similar to examples of Cycladic sauceboats in EC II. Later Lerna versions of the sauceboat are more vertical in their proportions (II-IV in the drawing), with the spouts stretched and angled out and upward, a stylization that is found elsewhere in EH II. Most of the ware is undecorated and plain, which focuses attention even more on the form itself. Like the EC frying pans, we remain unsure about the function of the sauceboats, which virtually disappear as a product at the end of EH II. Figure 2.5 also shows some characteristic bowls and saucers from EH II, some used for drinking

(A-E in the drawing). While these shapes are more practical in form and function, one can see a stylistic consistency, with turned-in rim and proportions that distinguish EH II pottery from other later periods (for example, compare these to the later MH Minyan ware in Figure 2.8, page 31).

Lerna is an important Early Helladic site for its well-documented excavation and because the site was destroyed and not rebuilt in later periods, preserving much of the EH occupation. The first two phases of the town, Lerna I and II, belong to the period EH I, and there appears to have been a smooth transition to Lerna III, the high point of the site in period EH II. There is evidence for the use of the plow at this time, and so likely greater agricultural production. The houses grew larger, being typically rectangular in shape, with a door on one short wall and either a squared end or rounded apse at the other end. A large town wall offering defense for Lerna was constructed, consisting of a double wall with space between.

The most distinctive structure in the later stages of Lerna III is the large House of the Tiles, named after the fired terracotta tiles that made up the roof of the structure (Figure 2.6). Tiles provided a more waterproof and durable roof than reed and thatch, but also increased considerably the weight on the walls of the structure, requiring more careful construction techniques. The house is much larger, 25 meters long and 12 meters wide, than the typical house and had a second story. The main entrance, marked by its framing and larger width, remained on the short end, and led past a short portico into a large square room. Smaller doors in the back of the large room and on the other end of the house led to additional rooms and access to the corridors at the side of the house, which provided stairs to the upper stories and give the name Corridor House to this type of building. Some of the walls were plastered, and the presence of a large collection of seal impressions in a self-contained small room on the south long side of the house suggests that the structure served as both residence and administrative center. The House of the Tiles and the settlement were destroyed at the end of EH II, c. 2200. The succeeding buildings were much smaller, rectangular buildings with apsidal ends, and a large circular tumulus was set up over the remains of the house, indicated by the circular line in the plan.

The Corridor House would have dominated the town visually, being both larger and taller than the other houses in the town. The large rooms on the first floor would have provided spaces in which groups could have assembled, while the rooms on the second floor would have provided restricted but elevated living quarters for the occupants. Its large scale and more costly structure and materials suggest that there had been changes in the social structure of the town from earlier phases. The presence of the storeroom with numerous seals, as we shall see next, suggests an administrative role for the building, and probably the emergence of an elite ruling family or group in the town. Whereas the plans of houses and towns in the first phases of the Bronze Age in Greece, like Myrtos, suggest a more horizontal type of social structure, the Corridor House at Lerna may indicate the emergence of social and political hierarchies in the middle of the third millennium.

As mentioned above, the small room on the south side of the Corridor House is only accessible from the exterior; inside were found 143 fragments of sealings on clay, with 120 different seal designs, some of them seen in Figure 2.7. Seals, made of stone or other materials, served an important role in the Bronze Age by serving to secure the tops of jars with clay to prevent tampering with their contents, and additionally signaled individual ownership of the contents. In the absence of writing, the unique design of a seal served throughout the ancient world to signal ownership and identity. Circular seals and seal impressions like those at Lerna are found throughout Bronze Age Greece, although not in these numbers in one location. These seals may have served an administrative purpose as a means for tracking payments of goods or crops of members of the community. The concentration of seals in a room of the Corridor House suggests that the building and its occupants served an administrative role. Whether the seals and house supported a ruling elite, who drew from the production of the residents, or served a communal function as a repository is debated, but in either case there was a centralized point of record-keeping and meeting space for the town.

As can be seen in the illustration of the seal impressions, most of the designs radiate from a central point to fill up the circular surface of the seal. Carved intaglio lines of a seal created raised lines in the impressions that they made when pressed in the clay, as can be seen in the drawings. Some of the designs use a swastika or bent pattern to create a more whirligig composition (S25, S26, S27), while

| |||

|

the symmetry of the other patterns might be better described as radial or centrifugal (S33, S40). Some of the seals, such as S34 and S32, show a bent-key motif that looks forward to the meander pattern found frequently in later Greek art, starting in the Early Geometric period as we shall see in Chapter 4. Some of the designs are tripartite and others quadripartite. Even within the limitations of the small field and the use only of engraved lines, one can still see that there was a wide range of designs and variations possible that would make each design unique and recognizable to both owner

and recipient of goods marked by the seal. Seals continued to be used into the first millennium and we will see that in the Middle Bronze Age intricate figural compositions would be used on elite seal rings and gems (see Figure 2.16, page 39).

Just how and why Lerna III was destroyed or by whom is uncertain. The succeeding periods, EH III, MH I, and MH II, appear to have been more modest in the number and size of settlements, not only at Lerna, but throughout mainland Greece. Shapes like the sauceboats disappear from pottery production, and there is a change in pottery technology that may indicate larger-scale social changes. Pottery from Lerna III had been handmade with coils, but in the EH III period the pottery wheel was adopted to finish the vessel and the surface is more burnished and glossy, techniques that had been developed in the Levant and Anatolia and made their way to the Aegean at this time.

One theory is that new people arrived in EH III who displaced the earlier population, resulting in the destruction of Lerna and other sites and a general decrease in the population. The discovery that the writing on tablets from the Late Helladic period was a very old form of Greek led to the hypothesis that it was a Greek-speaking people who settled on the mainland in EH III, but there is no evidence from this period to confirm what language the people of Early Helladic Greece spoke. It is possible that Greek-speaking peoples arrived even earlier, or that there were several waves of migration rather than a single invasion that resulted in the destruction of Lerna. Recent study has also indicated that there were significant environmental changes that took place during EH III, and this might explain the depopulation and abandonment of sites as agricultural production declined.

On the Greek mainland, the Middle Helladic period is certainly more modest generally, with many of the EH sites abandoned, especially in the interior of the region. There is an increase in settlements, population, and wealth beginning in MH III, and especially in LH I, that we will discuss later. One of the most distinctive products of the MH period is gray Minyan ware, like the three heavily restored drinking cups in Figure 2.8. These vessels are made using a potter’s wheel and have sharply defined edges and components like rims and feet; the surface is burnished, giving the cups a polished appearance. The two-handled design for a drinking cup is significant, in that their presence indicates a practice of shared or communal drinking. With two handles a host or pourer can use one handle to give the cup to a drinker, unlike a one-handled mug or goblet without handles. Two- handled cups first appear in the the later phases of the Early Bronze Age, and continue to be common and even predominant in later Greek art, as we saw in the kylikes in Chapter 1, reminding us of the social context in which drink was consumed.

protopalatial and neopalatial Crete

During the first phase of the Middle Minoan period we see the development of large palaces throughout Crete, giving rise to the term Protopalatial for the time corresponding to MM IB through MM II in the traditional chronology (c. 1900-1750 âñå). These palaces featured a large central courtyard surrounded by buildings, dwarfing in scale earlier houses and signaling the development of more centralized administration and a much greater degree of wealth. There is also evidence of more extensive trade contacts, both through the presence of materials like gold and ivory imported into Crete and through the export of Cretan works, like Kamares Ware pottery, to places like Egypt. These palaces were all destroyed around 1750 âñå, possibly due to earthquakes, but then rebuilt at a larger scale than before. The Neopalatial structures likely followed the general plan of their predecessors, but the vigorous rebuilding obliterated much of the remains of the Protopalatial structures. The

Neopalatial period encompasses both the end of the Middle Minoan period (MM III) and the beginning of Late Minoan (LM I). Most of the palaces are destroyed at the end of LM IA, probably due to damage associated with the eruption of Thera around 1625 âñå, and only the palace at Knossos is rebuilt and continues to function until the end of LM IB around 1490 âñå, when the Neopalatial period concludes. The palatial period on Crete not only marks a high point of art and architecture, but also signals a change from the less complex settlements of the Early Minoan period. Specialization of production at the palaces suggests an elite culture that reflects more centralized organization of agriculture, economic production, and trade, providing the resources and patronage necessary for the skills and materials used in the production of art and architecture.

We can readily see the change in artistic culture by examining a different approach to form and decoration in Middle Minoan pottery. Beginning in EM III, Minoan potters painted a coat of dark slip over the vase, and then added decoration in white on top of it. This fashion continued into the Protopalatial period (MM IB and MM II), by which time these wheel- thrown vases were both sharply defined in terms of their shape and architectural form and decorated with vibrant swirling designs by use of white and red paint on the dark surface (Figure 2.9). These Kamares Ware vessels, like this pitcher from the town of Phaistos, feature abstract motifs that derive from plant forms, but the emphasis is upon an energetic and visually dynamic design that leads the eye around and over the vase following the repeated linear patterns. The shape retains some of the stylized features that we saw in Vasiliki Ware, like a projecting and angular spout, but the shape is more vertical, adding to the sense of potential movement of the vase. Kamares Ware appears during the Protopalatial period and continues to be produced in a more restrained fashion into MM III and the Neopalatial period, suggesting that the destruction of the palaces did not destroy the system that built them.

|

To survey Minoan architecture and towns, we have to look at buildings from the Neopalatial period, but these probably follow the forms and functions of the earlier Protopalatial phase. The town of Gournia shows an increase in both the area and population of Minoan towns during the Palatial period compared to Early Minoan sites like Myrtos (Figure 2.10). The town is organized around a large square (3 in the plan), above which was a modest “palace” (5-6) that was probably more like a governor’s residence than the large palaces found at sites like Knossos and Phaistos. While more modest in scale than the large palaces like Knossos that we shall discuss next, the palace at Gournia dominates visually the town around it by its central and higher position and the use of

ashlar masonry. The open square could have been used for public functions like markets, as well as for rituals, but sitting above it, the palace would have dominated the activities of the square.

Gournia is built on a slope above a harbor, and three main roads run along the ridges, looping from the main square and back again (7, 10, and 2). Stairs and sharp inclines run east-west between the main traffic arteries. As in Myrtos, the houses are quite varied in their plans and configuration, but most were two stories with six to eight rooms, with storage on the lower floor and living quarters above. The houses continue to use many of the same materials as earlier, rough stone, mud brick, timber, and reeds. Many of the houses share exterior walls, unlike the isolated exterior walls of the palace, giving further visual distinction to the palace and showing the importance of a centralized administration in Minoan Crete.

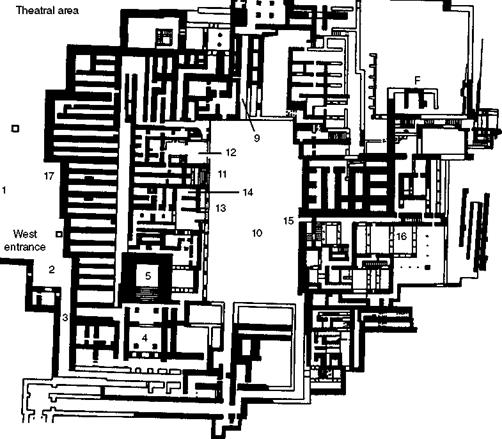

It is in the palaces of the Neopalatial period that we see the use of more finely worked stone and larger-scale rooms. The palace at Knossos, often called the Palace of Minos after the legendary king of Crete who built the labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur, is the largest of the palaces. As can been seen in the plan (Figure 2.11), the palace was built around a large rectangular courtyard (25 m x 50 m) set along a north-south axis. The surrounding structures were built two, three, or four stories high, with a shrine, throne room, and staircase on the west side of the court (13/14, 12, 11) and residential

area to the east (15). The walls were made of ashlar blocks of stone, as well as rougher stone, timber, rubble, mud brick, and plaster (Figure 2.12). Large wooden columns had a particular form that is distinctly Minoan: a smooth shaft that tapers downward from a large bulbous capital that is painted red and black. The plaster was made from burned limestone, making a durable coating to the walls. The plastered walls in Minoan palaces were covered with frescoes to make truly impressive rooms and passageways. The processed materials and their combination in construction to create staircases, corridors, windows, and openings required a skilled team of architects and builders and are by themselves a sign of the increased prosperity of Crete during this period. Indeed, at an area of roughly 20,000 square meters, the palace at Knossos is larger than the town of Gournia.

It is during the Protopalatial period that a writing system was developed, labeled Linear A, that remains mostly undeciphered today. Linear A inscriptions are found on sealings, tablets, storage vessels as wel

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-12-29; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1608;