middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 4 страница

to signify that the horse is on a beach and being driven into the water to tame it. The elaborate headdress marks the horse tamer as elite, as do his action, scale, and connection to the horse as a status symbol. The importance of the action is further signified by the four figures holding branches in the “background” at the top of the picture. These are thought to be a female chorus performing a ritual dance as part of the taming ceremony. The emphasis upon horse-taming ritual and choral performance, earlier than the subject appeared in Attic pottery, seems to reflect a particularly Argive agenda in the decoration of Geometric pottery.

In looking at these three large vases painted between about 750 and 740 (Figures 4.9, 4.11, and 4.12), we can see there is a common style that links the three regions where they were produced, but also differences in motifs, subjects, and purpose of the vases. All are Late Geometric and emphasize decorative bands covering the entire surface of the vase. The Attic vase emphasizes continuous figural friezes wrapped around the vase, the Argive krater makes more use of the metope panel for figural compositions, and the Euboean vase has elements of both. Running spirals are found in the later two, but the drawing of the horses differs. Here, the Euboean and Attic horses are closer to each other in style of drawing, more static, vertical, and streamlined, while the Argive horse is looser, more curvilinear, and given texture with the hairy mane and tail. Sorting out the potential relationships and i nfluences between regional styles is not easy. Certainly there are common stylistic elements that show a shared approach across regions, but the regional differences suggest exchange rather than centrifugal influence, going outward from a single center. For example, the use of figural imagery on Argive funerary vases comes later than its appearance in Attic art, but the appearance of dance scenes on vases is earlier in Argos than in Athens. Each region’s vases can be said to serve their own purposes, and when we add to this the connections with Cyprus and the Levant demonstrated in Euboean and other wares, we should see the Late Geometric period as one of ferment, change, and potentially cross-influences among the various centers of production.

In looking at these three large vases painted between about 750 and 740 (Figures 4.9, 4.11, and 4.12), we can see there is a common style that links the three regions where they were produced, but also differences in motifs, subjects, and purpose of the vases. All are Late Geometric and emphasize decorative bands covering the entire surface of the vase. The Attic vase emphasizes continuous figural friezes wrapped around the vase, the Argive krater makes more use of the metope panel for figural compositions, and the Euboean vase has elements of both. Running spirals are found in the later two, but the drawing of the horses differs. Here, the Euboean and Attic horses are closer to each other in style of drawing, more static, vertical, and streamlined, while the Argive horse is looser, more curvilinear, and given texture with the hairy mane and tail. Sorting out the potential relationships and i nfluences between regional styles is not easy. Certainly there are common stylistic elements that show a shared approach across regions, but the regional differences suggest exchange rather than centrifugal influence, going outward from a single center. For example, the use of figural imagery on Argive funerary vases comes later than its appearance in Attic art, but the appearance of dance scenes on vases is earlier in Argos than in Athens. Each region’s vases can be said to serve their own purposes, and when we add to this the connections with Cyprus and the Levant demonstrated in Euboean and other wares, we should see the Late Geometric period as one of ferment, change, and potentially cross-influences among the various centers of production.

sculpture

Small votive statues of animals or humans/gods, made out of terracotta or bronze, are the most common type of sculpture for the Geometric period, but there are a few remarkable figures found in graves to consider first. The Euboean terracotta statue of a centaur from the cemetery at Lefkandi dates to about the year 900 (Figure 4.13). The horse body was thrown like a pot and its decoration recalls that of late Protogeometric and Early Geometric pottery, but the centaur is remarkable both for its context and as a figural representation. First, there are individualized features, such as six fingers on the right hand, perhaps a sign of wisdom, and an intentional vertical gash on his left knee that appears to represent a scar. The left arm is broken, but was likely holding something that rested on the shoulder, such as a branch. The hand-modeled torso and head are fully three-dimensional and articulated. The face, in particular, has an appearance of attentiveness, quite unlike the typically unruly character of centaurs in Greek mythology. It has

been suggested that this centaur may be Cheiron, the wise centaur who was the tutor of Achilles and Asklepios and was wounded by Herakles, but this is conjectured on the basis of much later, identifiable representations of Cheiron.

The work was found in two pieces, the head in one grave and the body in a nearby grave in the Toumba cemetery at Lefkandi, just west of the remains of the large building discussed below. The head had been deliberately broken off before the burial, and the excavators have suggested that this represents some type of chthonic (i.e., concerning the underworld) ritual, and that a centaur at this time represents a guardian or protector for the deceased.

The work was found in two pieces, the head in one grave and the body in a nearby grave in the Toumba cemetery at Lefkandi, just west of the remains of the large building discussed below. The head had been deliberately broken off before the burial, and the excavators have suggested that this represents some type of chthonic (i.e., concerning the underworld) ritual, and that a centaur at this time represents a guardian or protector for the deceased.

Both the centaur and the context are unique, however, and without comparanda from other tombs or representations of centaurs, we cannot be sure of what it meant, only that it was a special type of creation that had particular meaning for the deceased and their family. Why the work was broken into two pieces, what was the relationship of the two deceased in the tombs, and whether the two burials were nearly simultaneous or separated by some time are questions that remain unanswered.

Both the centaur and the context are unique, however, and without comparanda from other tombs or representations of centaurs, we cannot be sure of what it meant, only that it was a special type of creation that had particular meaning for the deceased and their family. Why the work was broken into two pieces, what was the relationship of the two deceased in the tombs, and whether the two burials were nearly simultaneous or separated by some time are questions that remain unanswered.

Whereas the Lefkandi centaur uses a common medium of the Geometric period to create sculpture, a group of five female figures from a Late Geometric tomb in Athens uses an imported material, ivory (Figure 4.14). The largest of the five figures is the most detailed and shows a standing woman with both arms at her sides. The body is shaped like a three-dimensional version of the mourners on Late Geometric vases, but the higher waist and longer legs are closer to the mourners on the krater in Figure 4.9 than the earlier amphora in Figure 4.8. Like those women, this one is nude. This representation of female nudity becomes atypical in later Greek art, but in the case of the ivory statue it would not be unusual in sculptures of the Near Eastern goddess Astarte made in Syria or Phoenicia, the likely source of the ivory. The small cylindrical cap, usually called a polos, is also a feature of the goddess. Given that the proportions are similar to painted Geometric figures and that there is a meander carved into the polos, it is more likely that the artist was in Athens; whether Greek, Near Eastern, or Greek trained by a Near Eastern sculptor is less clear. The tomb also contained two faience lions that are Egyptian imports, more testimony to some of the cross-cultural currents at this time.

Other works show not only that was there trade in materials and finished work with the eastern Mediterranean, but also that there were foreign artists living and working in Greece during this period. A gold pendant found in a tholos tomb at Tekke, near Knossos in Crete, was part of a deposit of gold buried there when the chamber was appropriated by a Near Eastern family or group of goldsmiths as a storage vault and workshop (see Figure 11.12, page 281). We will discuss this work again when considering the relationship of Greek art and culture to the Mediterranean more broadly, but the pendant’s techniques, such as the use of filigree and granulation, and the subject matter, including the polos hats on the two heads and the heraldic type of composition, suggest that the goldworkers were from

north Syria and came to Crete sometime in the last half of the ninth century, perhaps as a result of the Assyrians subjugating that area, as John Boardman has suggested (Boardman 1967, 66-67).

Most Geometric sculpture is found outside of tombs in sanctuaries. The appearance of dancers and rituals on Late Geometric pottery reminds us that, whereas religion and ritual continued through the Early Iron Age, our evidence for its beliefs and practices is meager. Before 700, there is little evidence of temples as buildings and, before 800, there are relatively small traces of artifacts. Indeed, the ritual of Greek religion, which we shall discuss more in Chapter 7, involved animal sacrifices and offerings to the gods or heroes. One needed a place for burning the sacrificial victim, pouring the libations, and depositing the gifts, but a permanent structure for these rituals was not necessary. Mostly ritual took place out of doors where an altar and fire could be made and people could gather, hence an open space was more important than a structure. Unless a stone altar were built, there is little imperishable material from these acts unless the same spot is used repeatedly and the deposits develop into a tumulus or mound, or buildings are created to support the ritual or store the gifts.

This is the case at Olympia, where the second-century ce writer Pausanias (Paus. 5.13.8-11) tells us that the altar of Zeus at that sanctuary was 22 feet (6.7 m) high and made up of the ashes from the burning of the sacrificial animals. There are differing foundation accounts by Pausanias (Paus. 5.7.10 and 5.8.2) and the fifth-century bce poet Pindar (Ol. 1.67-88, 6.67-69, 10.24-25 and 57-59) that attribute the establishment of the cult at Olympia to Herakles honoring Zeus and Pelops, to Pelops honoring Zeus for his victory over king Oinomaos, or to Zeus honoring his victory over his father Kronos. Recent excavations in the area of the Pelopeion at Olympia have found terracotta and bronze figures of humans and animals, as well as pottery that can be dated back into the tenth century, showing that cult activity here dates from at least the Protogeometric period. The games at Olympia, too, have various foundation legends, but the custom of using the numbering of the Olympiads as a means for marking a chronological event or period in Greek history allows us to work backward to arrive at a traditional foundation date for the first Olympiad in 776 bce. Whether or not there was such a specific or single founding, the excavations at Olympia have revealed an increase in the number of offerings in the eighth century that corroborates the early importance of the site to Greeks not only from the area, but from many other regions of Greece as well.

| |||

| |||

The terracotta figures from Olympia are fairly simple and consist primarily of animals, including bulls, sheep, and especially horses, as well as human figures of charioteers, warriors, men, and some women, like the Late Geometric “Hera”-type discussed in the first chapter (see Figure 1.3, page 7). The early terracotta figures consist of very simplified and flattened shapes for the torso and limbs, projections for the nose and chin, and circular indentations to mark the eyes, nipples, and belly button. Indeed, the Hera-type looks very similar in form and detail to the “Zeus”-type figure found in larger quantities at Olympia, except that the genitals on the Hera-type are marked with a line rather than a projection. Without the marking of the genitals on these figures, they would be hard to differentiate, not unlike the figures on contemporary LG IA Attic funerary vases, where we often

distinguish gender on the basis of action rather than anatomy. Both Hera- and Zeus-types also look quite different from the terracotta figures of the late Mycenaean period (see Figure 3.14, page 64).

Many of the eighth-century votive figures are made out of bronze rather than terracotta, and include bulls and horses as common subjects (Figure 4.15). These figures are very clay-like in their form: tubes with swellings, pinches, and bends to define the body parts and small appendages for ears, horns, and tails. These figures are solid-cast bronze pieces, and this early work in bronze shows the influence of working with clay and wax in making the models and molds for casting. In spite of the differences in media, we can readily see a similarity between the votive terracotta and bronze sculptures and the animals and humans in contemporary vase painting.

Many of the eighth-century votive figures are made out of bronze rather than terracotta, and include bulls and horses as common subjects (Figure 4.15). These figures are very clay-like in their form: tubes with swellings, pinches, and bends to define the body parts and small appendages for ears, horns, and tails. These figures are solid-cast bronze pieces, and this early work in bronze shows the influence of working with clay and wax in making the models and molds for casting. In spite of the differences in media, we can readily see a similarity between the votive terracotta and bronze sculptures and the animals and humans in contemporary vase painting.

The rapid increase in the use of bronze figures as votive offerings in the eighth century is interesting in reflecting some of the changing social purposes of art during the Late Geometric period. We have already noted that the amount of metal as grave goods declines in the eighth century, and even the creation of monumental vases as grave markers does not continue beyond the Late Geometric I period. If these earlier uses of art in burials were to distinguish their elite patrons, then the growth in offerings, especially in the second half of the eighth century, suggests a new avenue for their patronage in sanctuaries rather than cemeteries. These small votives were relatively expensive items to acquire and then give away, but the ever accumulating deposits showed the social and religious importance of the gifts. Many were made by metalworkers at the site and sold to visitors to the sanctuary, but some may also have been brought to the site by visitors. Since the patrons were from all over Greece, this shared act of acquiring and giving these small bronzes helped to create a visual culture that was Panhellenic, forming bridges across regions and a shared social structure, particularly one that emphasized the elite as a class.

The second major type of bronze artifact found at Olympia is the tripod. Originally a three-legged cooking pot that could be set over a fire, the bronze tripod became an elite and monumental prize in contests and a gift to sanctuaries. The reconstruction of a late eighth-century tripod (Figure 4.16) shows the legs made out of sheets of metal that join to a bowl made of

a hammered sheet of bronze. Ring handles are a practical legacy of its cooking function, but now these have been made into thin disks with cast and engraved patterns on them. Solid-cast figures further decorate the handles, including horses and human figures, usually in pairs holding the sides of the ring. One such handle support is a nude warrior wearing a crested helmet (Figure 4.17). The warrior is quite similar in its proportions and abstraction to figures in contemporary vase painting or the ivory woman from Athens (Figure 4.14, page 85).

In the Iliad, a tripod is the top prize for the chariot race at the funeral games of Patroklos (23.698702), and we should consider that the combination of form, size, and material made this an important and expensive work of art, one that was likely commissioned and brought to Olympia rather than

purchased there. On a leg from a tripod made in Crete and dedicated at Olympia near the end of the eighth century, we see action scenes like those in Late Geometric II vase painting (Figure 4.18). The surface of the leg is divided vertically into metope panels, with two helmeted warriors fighting over a tripod in the upper panel and two “lions” fighting each other below. The warriors are identical in form, leaving the viewer to wonder if this is meant to be a prototypical scene of competition and struggle, perhaps symbolizing the competitions that the tripod celebrated, or is this an early effort to represent a mythological story, such as the struggle of Apollo and Herakles over the Delphic tripod? Since the warriors are nearly identical, a mythological interpretation is probably less likely since we cannot determine who is the god and who is the hero. We should certainly see the predators fighting below like a Homeric simile, in which the poet compares a warrior’s prowess and actions to an animal like a lion. Perhaps we should think of the warriors, too, as a simile for the donor of the tripod, perhaps given in honor of a victory at Olympia.

purchased there. On a leg from a tripod made in Crete and dedicated at Olympia near the end of the eighth century, we see action scenes like those in Late Geometric II vase painting (Figure 4.18). The surface of the leg is divided vertically into metope panels, with two helmeted warriors fighting over a tripod in the upper panel and two “lions” fighting each other below. The warriors are identical in form, leaving the viewer to wonder if this is meant to be a prototypical scene of competition and struggle, perhaps symbolizing the competitions that the tripod celebrated, or is this an early effort to represent a mythological story, such as the struggle of Apollo and Herakles over the Delphic tripod? Since the warriors are nearly identical, a mythological interpretation is probably less likely since we cannot determine who is the god and who is the hero. We should certainly see the predators fighting below like a Homeric simile, in which the poet compares a warrior’s prowess and actions to an animal like a lion. Perhaps we should think of the warriors, too, as a simile for the donor of the tripod, perhaps given in honor of a victory at Olympia.

We should note that these bronze warriors are nude, and briefly consider nudity more broadly as a recurring feature of Greek art. Clearly, real warriors did not fight nude, but the nude warriors of Geometric art begin a long tradition of heroic nudity in art in which gods and heroes are shown fighting and otherwise interacting in the nude. The question of nudity is more complex than simply a reference to heroes and myths, however, in that the Greeks did actually compete athletically in the nude. According to one tradition, a runner lost his loincloth in an early footrace at Olympia but won, starting a new custom. The nudity in art, however, is earlier than this, and is further complicated by considerations of gender. While early terracotta figures distinguished male and female by indicating the genitals, the earliest painted human figures did not have any signals of gender: no genitals, no breasts, and no clothing. The mourners on the Dipylon amphora must include women, but there is no sign of their sex, and only the gender association of their action. The proportions of the figures in the earliest figural representations are the same for men and women, whether terracotta or painted figures.

It is not until the last half-century of the Geometric period when we begin to see a more systematic distinction of nude versus clothed figures, as on the LG II Attic skyphos we saw earlier (see Figure 4.10, page 81). We should, then, consider the question of nudity and clothing as reflecting a differentiation of gender roles in the emerging polis. Men fight and compete in athletics; nudity emphasizes their physical action even in the silhouette style of the Geometric period. That many of the men wear helmets while nude emphasizes their role as warriors, and the popularity of nude warriors at Olympia emphasizes the importance of athletics as part of a warrior ethos. Women’s roles, at least in Geometric art, are more limited to ritual, either dancing or singing in public performances, or as mourners. We will consider gender in Greek art further in Chapter 13, but we should note its early, if still inconsistent, differentiation here in the Late Geometric period.

The developing interest in action and the recurring debate as to whether some Geometric scenes are mythological or not can be found in a bronze group showing a nude warrior confronting a centaur (Figure 4.19). The arms of the two figures interlock with one another, but the right forearm of the

man is broken off and the point of a spear protrudes from the left side of the centaur’s torso, surely showing the man has struck the centaur with his weapon. The man wears a conical hat but is otherwise nude, like the warrior from the tripod handle. The front part of the centaur is virtually a replica of the hero, including the hat, but at a smaller scale; the hind quarters of a Geometric horse stick out from his back to make him a centaur. Furthermore, the centaur has human rather than horse genitalia and can be seen not so much as a truly hybrid creature as a pastiche. Of course, the artist is free to imagine a centaur in any number of ways, and this is not the only centaur to be so configured with a human front half in Greek art, so its identity, like the Lefkandi centaur, remains a mystery.

architecture

architecture

Our knowledge of Geometric architecture is very limited. Most of the building material was perishable: wood, mud brick, and thatch. Furthermore, places with long histories of settlement such as Athens have seen most of the earliest levels obliterated in the rebuilding and developments over many centuries. Later buildings constructed out of stone, for example, needed large foundations for support, and the builders dug through the layers beneath the ground, destroying much of what was there. Given the general impoverishment and lack of monumental work in the Protogeometric period, the discovery of a large, tenth-century building in the Toumba cemetery at Lefkandi came as a surprise. The building, shown in reconstruction (Figure 4.20), was more than 50 meters long and had a porch on the east end and a rounded apse on the opposite western end, much of it missing. The walls were made of mud brick with timber that rested on a large socle of roughly worked stones about 1 meter high. Wooden columns ran down the center of the building, and columns lined the exterior wall supporting the eaves of the roof. A timber roof frame supported a steep thatch roof. The floors and walls were at least partially finished with plaster, but there was not much sign of wear from long habitation.

The building was divided into three main sections. A porch led into a square room at the east end. Beyond that was a large rectangular room about 22 meters long in the center of the structure. Beyond that was a passageway with two small rooms that led into the apse, that likely served for storage. In almost the center of the building were two shafts cut into the floor of the

central room, one holding the remains of four horses along with bronze and iron objects. The second shaft contained two burials. One was a cremation burial of a man, with the ashes placed in a bronze amphora from Cyprus dating to the late thirteenth or twelfth century все and a sword and spear placed next to it. The other was a female inhumation burial, with elaborate jewelry and disks placed over the breasts of the woman and other offerings such as an iron knife with ivory handle placed around her. Both tombs date to about the middle of the tenth century. This means that the bronze cinerary amphora was about 200 years old at the time it was used for the burial, and so rare both by

age, material, and origin. Above the graves was set a contemporary ceramic krater made by a Euboean potter.

age, material, and origin. Above the graves was set a contemporary ceramic krater made by a Euboean potter.

The relationship of the pair of tombs to the building is uncertain from the excavation. The building is unusual in that it was deliberately demolished not long after the burials to create a mound over the tombs. One theory is that the building was built over the tombs, perhaps as a heroon or hero shrine, although there is no evidence of later cult activity associated with the building. The second theory is that the structure was a residence that had been built for the deceased, who were buried under its floor, and the building was then demolished and made into a tumulus. If so, the building had not been used for long and might have been unfinished at the time of the burials. Whichever theory is correct, the building is certainly monumental in scale, easily seven times the size of a typical house such as those at Zagora that we will discuss below. The grave goods are extraordinary, and whether a house or tomb, the grand scale and large central room recall the mega- ron of the Mycenaean palaces. Whether the man buried beneath the floor fashioned himself as a king or “big man,” the monumentality of the buildings sets up a contrast to the scale of later Geometric architecture. After the creation of the tumulus, the site then became the focal point of a large cemetery to the east of the building. Two of the earliest graves there, dating around 900, contained the head and body of the centaur discussed earlier (see Figure 4.13, page 84). Many other elaborate grave goods, including contemporary imported work from the Near East, were found in the cemetery.

Was the man buried in the building/tumulus regarded as a hero of the community and the subject of a cult afterward, or was he perhaps the ruler and founder of a ruling family whose members were later buried in the adjacent cemetery? The cremation of the man’s body and placement of his ashes in a bronze amphora look forward to the cremation of Patroklos described over a century later in Iliad 23.250-257 (tr. Lattimore 1951, 457):

First with gleaming wine they put out the pyre that was burning, as much as was still aflame, and the ashes dropped deep from it.

Then they gathered up the white bones of their gentle companion,

weeping, and put them into a golden jar with a double

fold of fat, and laid it away in his shelter, and covered it

with a thin veil; then laid out the tomb and cast down the holding walls

around the funeral pyre, then heaped the loose earth over them

and piled the tomb, and turned to go away.

For now, we have to recognize that the circumstances at Lefkandi are highly unusual and difficult to interpret with certainty, except to say that the scale and extravagance of the building and its contents, as well as its demolition, signify the importance of the deceased to the community, both at the time of death and afterward.

While the Lefkandi building was atypical, we have a few surviving examples of town architecture during the Geometric period that tell us about more ordinary villages and houses. Excavations at Zagora on the island of Andros have revealed a town that was built in two phases on the top of a hill

4.20 Reconstruction of the House at Lefkandi, 1000-950 все. After M. R. Popham, P. G. Calligas, L.

H. Sackett, J. Coulton, and H. W. Catling, Lefkandi II: The Protogeometric Building at Toumba. Part 2: The Excavation, Architecture and Finds, British School at Athens. Supplementary Volumes, 23 (Athens, 1993), pl. 28. Reproduced with permission of the British School at Athens.

H. Sackett, J. Coulton, and H. W. Catling, Lefkandi II: The Protogeometric Building at Toumba. Part 2: The Excavation, Architecture and Finds, British School at Athens. Supplementary Volumes, 23 (Athens, 1993), pl. 28. Reproduced with permission of the British School at Athens.

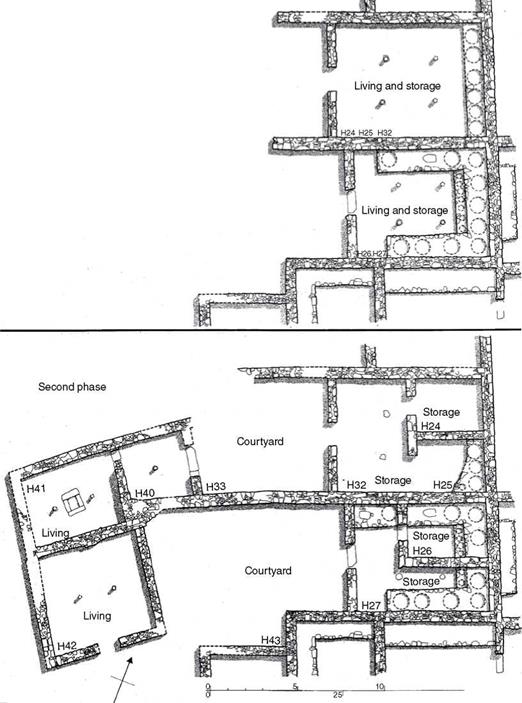

overlooking the sea, well suited for defense but without a water supply within the perimeter walls (Figure 4.21). The first phase of the town was built in the middle of the eighth century (c. 775-725) and consisted of one-room houses with a porch or pronaos in front of them, clustered in rows facing outward in the same direction (Figure 4.22, top). The rooms are modest in size, about 6-7 meters wide and 7-8 meters deep. Many of the rooms served as both living and storage areas, the latter consisting of stone benches with circular openings that could hold large terracotta storage pithoi or jars. The houses underwent extensive remodeling between 725 and 700, after which the town was abandoned. In this second phase, additional rooms were built and interior courtyards were formed for each house, separating living from storage areas (Figure 4.22, bottom). This created a series of houses, each of which had a central focus on the courtyard. While it created more functional space for the inhabitants and their activity and storage needs, the new plan also served to isolate each house from activities in the others.

overlooking the sea, well suited for defense but without a water supply within the perimeter walls (Figure 4.21). The first phase of the town was built in the middle of the eighth century (c. 775-725) and consisted of one-room houses with a porch or pronaos in front of them, clustered in rows facing outward in the same direction (Figure 4.22, top). The rooms are modest in size, about 6-7 meters wide and 7-8 meters deep. Many of the rooms served as both living and storage areas, the latter consisting of stone benches with circular openings that could hold large terracotta storage pithoi or jars. The houses underwent extensive remodeling between 725 and 700, after which the town was abandoned. In this second phase, additional rooms were built and interior courtyards were formed for each house, separating living from storage areas (Figure 4.22, bottom). This created a series of houses, each of which had a central focus on the courtyard. While it created more functional space for the inhabitants and their activity and storage needs, the new plan also served to isolate each house from activities in the others.

This scheme of rooms arranged around a central court would become the predominant house type in Greek architecture, as we will see in several examples in the next chapter. The development of this dense clustering of independent but similar houses has been linked to the development of the social structure of the polis. Rather than a town dominated by elite individuals who ruled on the basis of their personal and family connections and lived in palatial structures, power in the polis was invested in institutions and laws emphasizing corporate oversight and communal participation, with the citizens

| | | |  |

|

|

| First phase |

| 9. Plans of houses H24-H25-H32-H33-H40-H41 and H26- H27-H42-H43. First and second phases (J. J. Coulton) |

| ___ Meters 50 Feet |

being roughly equivalent before the law (isonomia). Citizenship was limited to freeborn men, excluding women, immigrants, and slaves, although each of these groups had some legal status and protections. The houses of citizens in classical Greece were inwardly focused, autonomous units without great distinction in terms of size or exterior decoration. The housing at Zagora has some of these same features, built at the same time that we see emerging signs of the polis in the Iliad and other sources.

As the remains of vase painting, sculpture, and architecture suggest, the long centuries of the Protogeometric and Geometric periods witness the beginnings of the development of the polis in place of the Bronze Age palace as the basic structure of society. While the elite continuously find

As the remains of vase painting, sculpture, and architecture suggest, the long centuries of the Protogeometric and Geometric periods witness the beginnings of the development of the polis in place of the Bronze Age palace as the basic structure of society. While the elite continuously find

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 923;