middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 5 страница

ways of distinguishing themselves, at first through elaborate grave goods, followed by grave markers and then their dedications in sanctuaries, the artistic developments that they patronized gradually became more diffuse and common. In the latter half of the eighth century new scenes emerge that reflect the emerging collective identity of the polis and the important activities of the lives of its members. One final example shows both how Geometric art could express the events and identity of its users and how the abstract and silhouette forms and their formulaic composition were limited in their ability to develop new meanings.

| |||

| |||

A large bowl in the British Museum that is thought to have been found in Thebes is a product of an Attic workshop around the year 730 (Figure 4.23). The bowl is a special shape, a louterion, associated with heating water for washing, and so would be appropriate for a ritual like the washing of a bride, corpse, or guest. The decoration on the shoulders of the vase includes some of the largest figures painted in the Geometric period. A large ship with two lines of rowers in a combination of profile and bird’s-eye type of view takes up most of the panel between the handles, while two very large figures, a man and woman, stand before a ramp at the ship’s stern, preparing to board it. He is nude and grabs hold of her by the wrist, leading her to the ship. She holds up a wreath in her hand and wears a dress.

The question that has puzzled scholars is whether this is one of the abductions found in Greek myth, such as when Theseus abducts Helen before her marriage to Menelaos, or Paris takes Helen to Troy after her marriage? Is it Theseus taking Ariadne, whose “crown of light” helped him to slay the Minotaur? No story quite fits the image and it has been viewed consequently as a generic abduction/ marriage scene, equivalent to later marriage scenes in which the bridegroom leads the bride by the wrist from her home to his (see Figure 13.4, page 326 for the procession part).

More recently, Susan Langdon has proposed that this bowl might have been commissioned for an Athenian bride who was marrying a man from outside Athens, perhaps Thebes, and so the pot, which would be appropriate for use in the ceremonial washing of the bride, would be an idealized representation and marker of the actual wedding (Langdon 2008, 19-32). The atypical subject matter would suggest that the work was a special commission, and would proclaim the status of both bride and groom on the occasion. The artistic difficulty is that the specific meaning, whether mythological or social, created by its commissioning and use is lost once there is no one left to remember and explain the story and circumstances to a viewer.

|

references

Blegen, C. W. 1952. “Two Athenian Grave Groups of about 900 B.C.” Hesperia 21, 279-294.

Boardman, J. 1967. “The Khaniale Tekke Tombs, II.” Annual of the British School at Athens 62, 57-75.

Homer, Iliad. 1951. The Iliad of Homer, tr. R. Lattimore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Langdon, S. 2008. Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 B.C.E. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Liston, M. A. and J. K. Papadopoulos. 2004. “The ‘Rich Athenian Lady’ Was Pregnant: The Anthropology of a Geometric Tomb Reconsidered.” Hesperia 73, 7-38.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. D. 1995. “Reading Pictorial Narrative: The Law Court Scene of the Shield of Achilles.” In J. B. Carter and S. P. Morris, eds. The Ages of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Vermeule. Austin: University of Texas Press, 315-334.

Whitley, J. 1991. Style and Society in Dark Age Greece: The Changing Face of a Pre-Literate Society 1100-700 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

further reading

Hurwit, J. M. 1985. The Art and Culture of Early Greece, 100-480B.C. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Langdon, S., ed. 1993. From Pasture to Polis: Art in the Age of Homer. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Langdon, S. 2008. Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 B.C.E. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snodgrass, A. M. 2000. The Dark Age of Greece: An Archaeological Survey of the Eleventh to the Eighth Centuries BC, new edition. New York: Routledge.

Whitley, J. 1991. Style and Society in Dark Age Greece: The Changing Face of a Pre-Literate Society 1100-700 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

contexts I: CIVIC, domestic, and funerary

Timeline

The City and its Spaces The Agora

Houses and Domestic Spaces Textiles

The Symposion Graves

Textbox: Agency References Further Reading

A History of Greek Art, First Edition. Mark D. Stansbury-O’Donnell.

© 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

timeline

| Sculpture/Tombs | Pottery/Tombs | Buildings/Cities | |

| 800-700 | 760-750 Dipylon amphora [4.7] end 8th cent. Tomb XI in Agora at Athens | 775-725 Zagora, phase I [4.22] 725-700 Zagora, phase II [4.22] | |

| 700-600 | |||

| 600-500 | c. 550 Kore of Phrasikleia [8.13] c. 530 Kouros from Anavyssos | 600-590 Early Corinthian krater with symposion 525-490 Pottery from Well 2:4 in the Agora, Athens [1.10] | 600 Founding of Poseidonia/ Paestum |

| 500-400 | 477/476 Tyrannicides | 450-420 Attic white-ground lekythoi | 480-400 Development of the classical Agora in Athens c. 430 Founding of Olynthos |

| 400-300 | c. 400 Stele of Hegeso | c. 336-311 Tomb II at Vergina | 348 Destruction of Olynthos mid-4th cent. Founding of Priene |

| 300-200 | |||

| 200-100 | c. 150 Stoa of Attalos in Athenian Agora |

| A |

s we saw in Chapter 4, Greek works of art served a purpose, whether as grave goods, grave markers, votive offerings, or potential wedding gifts. In some cases they were made specifically for the function and occasion, such as the monumental Dipylon amphora that served as a funerary marker (see Figure 4.7, page 78), or they might have been taken from one context and then repurposed, such as the jewelry of the rich lady buried in the Agora becoming her grave goods (see Figure 4.6, page 76). Context and function not only shape the form and subject matter of artworks, but also help to frame meaning for their makers, owners, and viewers. The setting and purpose of a work, then, are essential to understanding its role as both art and artifact. Broadly speaking, there are four major contexts in which Greek art is found: sanctuaries, civic spaces such as the agora, domestic spaces, and finally graves and cemeteries. Already we have seen that in the Geometric period these contexts were not static, but changed to meet the needs of Greek society and culture. We will begin by looking at the overall plan of the city and its main public space, the agora, and then turn to housing and cemeteries. We will return in Chapter 7 to the developments to be found in sanctuaries, including the temple and the development of the architectural orders.

In exploring the civic, domestic, and funerary realms, we will review some of the works in the Geometric period, but mostly we will be looking ahead to some of the developments that take place in later periods. In taking a more diachronic view, we can see how the contexts either changed or remained the same over time. Accordingly, some important examples of context are found in other chapters focused upon chronology, so we will be making reference throughout this and the other contextual chapters in this book to works in other chapters. Admittedly, looking ahead or behind at images in other chapters can be time-consuming, but one may also regard it as a reflection of the multiple layers of monuments and artifacts that accumulated in the Greek city and that a stroll through the ancient agora or sanctuary was a historical as well as immediate experience. In this chapter, then, we will pick up with the emerging polis that we see in Zagora and observe the archaic, classical, and Hellenistic developments that followed in the key areas of civic life and spaces.

the city and its spaces

The growth in population and economic activity during the Geometric period led not only to the expansion of towns like Athens, which had been continuously settled since the Bronze Age, but also to the foundation of new towns like Zagora, and, beginning in the eighth century, to new settlements throughout the Mediterranean as Greek cities founded colonies in southern Italy, Sicily, Asia Minor, and elsewhere. As we saw at Zagora (see Figures 4.21 and 4.22, pages 92, 93), houses were laid out in clusters with some common walls, but the overall plan is asymmetrical and uneven. A defensive wall helped to define the boundary of the city as well as to protect it. Besides housing, a town also had to have spaces for markets and civic gatherings, an area usually labeled the agora, but at least at Zagora this did not require specific buildings. There was also an area for an altar and religious rituals, but there was not an actual temple until later, after the settlement itself had been abandoned. Towns also needed places for burials, and these were located outside the inhabited area, usually along or near roads leading to the city.

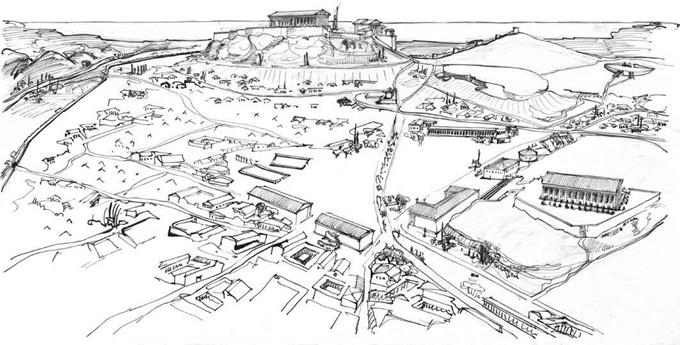

Zagora is important because it gives us a picture of the earliest development of the city, particularly in terms of its housing. The earliest phases of Athens are much harder to recover because of the vast expansion of the city in later periods and the rebuilding/destruction of its earliest civic and domestic buildings. Looking ahead to the fourth century, we can see that the basic division of the city’s interior into sanctuaries, the agora and civic spaces, and housing still holds. In the reconstruction drawing by John Travlos, looking from the northwest, the city is dominated by the Acropolis in the upper center of the picture, with the Parthenon in the middle of the view and the Propylaia or entrance on the right (west) side (Figure 5.1). We will discuss the sanctuary in more detail in Chapter 7, but this view shows that the temple was the largest and tallest standing structure of the city and was distinguished

|

visually by the colonnade that surrounded it. The road leading to the Acropolis was the Panathenaic Way, the route followed by the procession of Athenians from the Dipylon Gate in the city walls to the Acropolis.

visually by the colonnade that surrounded it. The road leading to the Acropolis was the Panathenaic Way, the route followed by the procession of Athenians from the Dipylon Gate in the city walls to the Acropolis.

The Panathenaic Way cuts diagonally in the picture and goes through the large open space of the Agora. The most noteworthy feature about an agora is that it is an open space within the densely packed streets and houses inside the city walls. This provided an area where markets, processions, and contests could be held. By the fifth century, the area today known as the classical Agora in Athens was taking shape and included a variety of buildings. Most characteristic were the series of long rectangular buildings with open colonnades called stoas that were built along the boundaries of the Agora. In the drawing, these line the north and south sides of the Athenian Agora and the northwest corner. Along the west boundary of the Agora were buildings dedicated to the city government, as we shall see later in this chapter. Beginning in the middle of the fifth century the Athenians also built the Hephaisteion above the Agora on its west side, a temple dedicated jointly to Hephaistos and Athena. Like the Acropolis to the southeast, this sanctuary is on a high place with the temple as the central focal point with limited access points to the sanctuary. There were also altars, memorials, and other monuments in the Agora, some of which we shall see later in this chapter.

The upper right section of the drawing shows the line of hills that bounded Athens on the southwest. At the far upper right is an area that was originally the bowl-shaped slope of the Pynx Hill. This is where the ekklesia of Athenian citizens met to make decisions as part of the democratic constitution of the city in the fifth century. At the beginning of the fourth century, the area was transformed by a large retaining wall to create theater-like seating for the citizens to hear speeches and proposals. From here, as we saw in Figure 1.9 (page 13), Athenians were in a position to see the full splendor of the Periklean building program while considering the polis’s affairs. A road leads from the Pynx to the southwest corner of the Agora, linking markets and governance.

|  |  |

|

The remaining areas of the city were filled with smaller houses and much less open space, densely clustered together along irregular roads that navigated around the terrain, particularly the hills of the Acropolis, the Areopagos, and the Pynx, seen on the top right of the drawing.

The irregularity of Athens is a reflection of its long history and dramatic expansion. John Papadopoulos has recently suggested that most of the Dark Age population of Athens lived on the Acropolis, with the semi-industrial pottery production area and cemeteries located below in the area of what became the classical Agora (Papadopoulos and Schilling 2003). There may have been additional small settlements or neighborhoods below the Acropolis with their own cemeteries, such as those found in the area of the Dipylon Gate (Figure 5.2). As the city expanded in population, it would have had to build up areas below the Acropolis, and the archaic Agora was probably located to the east of the Acropolis, along with housing. The Acropolis during the sixth century became more exclusively a sanctuary with a temple dedicated to Athena and other buildings.

The destruction of the city by the Persians in 480/479 bce required not only rebuilding, but also apparently a reorganization of the city. The classical Agora, the one dominated today by the rebuilt second-century Stoa of Attalos housing the site’s museum (see Figure 5.6, page 105), was founded and became a new focal point of commercial and civic activity. The pottery industry moved further out to the area of the Dipylon Gate and gave the name to this quarter of the city, the Kerameikos. The Agora housed the meeting buildings of the civic government, with the larger area for the ekklesia located on the plateau of the Pynx.

The terrain and episodic development of a city like Athens makes its overall plan and organization irregular. In founding new colonies, however, cities were planned in a more regular and precise fashion. Usually these colonies were established in areas with flatter, arable land, as agriculture was initially the primary economic activity of the new sites. The land, called the chora, was divided by a grid into parcels for farms. Rural sanctuaries were often used to mark the boundaries of the territory. Some land was set aside for a city and laid out using a grid system, as can be seen in the plan of Poseidonia (modern Paestum) in southern Italy (Figure 5.3). This city was founded around 600 bce by colonists from Sybaris, itself an Achaian colony founded in the late eighth century on the south coast of Italy. The boundaries of the city, marked by walls, were mostly straight, but meandered on the western boundary due to the coastline and marsh. Within the walls, a regular grid established long rectangular blocks running north-south. The central north-south section of the city was defined by three large areas about 5.5 blocks deep. Two of these, at the north and south end, were made into sanctuaries. The oldest temple, dedicated to Hera, was built around 550 bce on the south section (1 on the plan) (see Figure 7.7, page 163). The sanctuaries had enough space for subsequent temples to be built as the city developed, including a second temple to Hera in the south (2) and one to Athena in the north (4). At the center were the civic spaces of the agora (around 3), now built over by the remains of the Roman forum and its structures. The main roads of the city intersected at the southwest corner of the agora and led out to the four main gates. The rest of the city was dedicated to housing and workshops and much more densely packed buildings, but it is probable that only some of this land was used initially. In planning their cities, the colonists allowed room for future growth of the population that would conform to the original design. Cemeteries, the last major requirement for civic planning, were located outside the city walls, primarily along the roads leading to the north and south.

The terrain and episodic development of a city like Athens makes its overall plan and organization irregular. In founding new colonies, however, cities were planned in a more regular and precise fashion. Usually these colonies were established in areas with flatter, arable land, as agriculture was initially the primary economic activity of the new sites. The land, called the chora, was divided by a grid into parcels for farms. Rural sanctuaries were often used to mark the boundaries of the territory. Some land was set aside for a city and laid out using a grid system, as can be seen in the plan of Poseidonia (modern Paestum) in southern Italy (Figure 5.3). This city was founded around 600 bce by colonists from Sybaris, itself an Achaian colony founded in the late eighth century on the south coast of Italy. The boundaries of the city, marked by walls, were mostly straight, but meandered on the western boundary due to the coastline and marsh. Within the walls, a regular grid established long rectangular blocks running north-south. The central north-south section of the city was defined by three large areas about 5.5 blocks deep. Two of these, at the north and south end, were made into sanctuaries. The oldest temple, dedicated to Hera, was built around 550 bce on the south section (1 on the plan) (see Figure 7.7, page 163). The sanctuaries had enough space for subsequent temples to be built as the city developed, including a second temple to Hera in the south (2) and one to Athena in the north (4). At the center were the civic spaces of the agora (around 3), now built over by the remains of the Roman forum and its structures. The main roads of the city intersected at the southwest corner of the agora and led out to the four main gates. The rest of the city was dedicated to housing and workshops and much more densely packed buildings, but it is probable that only some of this land was used initially. In planning their cities, the colonists allowed room for future growth of the population that would conform to the original design. Cemeteries, the last major requirement for civic planning, were located outside the city walls, primarily along the roads leading to the north and south.

The city of Olynthos shows a combination of planned and unplanned development (Figure 5.4). A small town had developed on the south hill of the modern site by the Geometric period and remained irregular in plan. Just before the start of the Peloponnesian War, several cities on the Chalkidian peninsula rebelled against the rule of Athens and fought against it in the ensuing conflict. At that time there was an anoikismos, or “moving inland” of some of the population of these cities to a larger and more defensible place with good agricultural land. Like the colonies in Italy, Sicily, and elsewhere, this new foundation was laid out on a grid, in this case along the north hill below the older settlement. The population was a mixture of the natives as well as Bottiaians, Chalkidians, and other immigrants. An agora was marked out along the west side of the city near the city wall, and cemeteries

The city of Olynthos shows a combination of planned and unplanned development (Figure 5.4). A small town had developed on the south hill of the modern site by the Geometric period and remained irregular in plan. Just before the start of the Peloponnesian War, several cities on the Chalkidian peninsula rebelled against the rule of Athens and fought against it in the ensuing conflict. At that time there was an anoikismos, or “moving inland” of some of the population of these cities to a larger and more defensible place with good agricultural land. Like the colonies in Italy, Sicily, and elsewhere, this new foundation was laid out on a grid, in this case along the north hill below the older settlement. The population was a mixture of the natives as well as Bottiaians, Chalkidians, and other immigrants. An agora was marked out along the west side of the city near the city wall, and cemeteries

N

Meters

|

were placed beyond the wall to the west. The excavations found no sanctuaries within the city, and these may have been all extramural. The rectangular grid blocks ran east-west and were filled with rows of houses set back to back. As the city expanded, a new area, the “Villa Section," was built outside the walls but mostly aligned with the original grid. The houses of Olynthos are among the best preserved in mainland Greece due to the fact that Philip of Macedon besieged and destroyed the city in 348 все, leaving the houses in ruins that were not rebuilt, as they were in Athens and other sites. We will look at the design of these houses and some of their contents later in this chapter, but for now it is important to note that the houses are equal in the size of their lots and are oriented toward the south to take advantage of the sun for light and warmth in the winter. One advantage of the grid plan is that it provides an opportunity to make equal provision to the residents of the city. This did not prevent strife from developing in some cities, but it did accord with the principles of government and rule that were later articulated by Plato and Aristotle.

The grid plan is often associated with Hippodamos of Miletos, who was active in the second half of the fifth century and, according to Aristotle (Pol. 1267b22-1268a14), laid out the harbor town of Piraeus near the city of Athens. As we have seen, grid planning is found in new foundations much earlier than that, and it continued to be used when possible into the Hellenistic period, as can be seen in the city of Priene in Asia Minor (Figure 5.5). The city was initially planned as a deep-water port by the ruler of Halikarnassos, Mausolos, in the mid-fourth century, but most of its construction took place after the conquest of the area by Alexander the Great in 334 все. Despite the uneven terrain of the site, the city was laid out on a grid within the city walls. An agora was placed at the center of the city on flatter land, with stoas on the north side facing south. There are two major sanctuaries inside the city. A small sanctuary of the healing god Asklepios is to the east of the agora, but is entered from the residential area on the east side. A large temple dedicated to Athena is to the northwest of the agora on a terrace. North of the agora is a theater, built against the rising slope toward the high acropolis. A gymnasion is between the theater and the Asklepion, while just inside the city walls on the south side is a race course. As the reconstruction drawing shows, the houses were densely packed within the blocks, but the slope provided additional exposure to sunlight for each of the houses. We will look at some of the finds from the houses later in this chapter.

The grid plan is often associated with Hippodamos of Miletos, who was active in the second half of the fifth century and, according to Aristotle (Pol. 1267b22-1268a14), laid out the harbor town of Piraeus near the city of Athens. As we have seen, grid planning is found in new foundations much earlier than that, and it continued to be used when possible into the Hellenistic period, as can be seen in the city of Priene in Asia Minor (Figure 5.5). The city was initially planned as a deep-water port by the ruler of Halikarnassos, Mausolos, in the mid-fourth century, but most of its construction took place after the conquest of the area by Alexander the Great in 334 все. Despite the uneven terrain of the site, the city was laid out on a grid within the city walls. An agora was placed at the center of the city on flatter land, with stoas on the north side facing south. There are two major sanctuaries inside the city. A small sanctuary of the healing god Asklepios is to the east of the agora, but is entered from the residential area on the east side. A large temple dedicated to Athena is to the northwest of the agora on a terrace. North of the agora is a theater, built against the rising slope toward the high acropolis. A gymnasion is between the theater and the Asklepion, while just inside the city walls on the south side is a race course. As the reconstruction drawing shows, the houses were densely packed within the blocks, but the slope provided additional exposure to sunlight for each of the houses. We will look at some of the finds from the houses later in this chapter.

|  |

5.5 Reconstructed view of Priene, later 4th-3rd cent. все. Drawing by Z. Wendel, from W. Hoepfner and E.-L. Schwandner, Haus und Stadt im klassischen Griechenland (Berlin/ Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1994), Fig. 183. Used with permission of Hans Goette and the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Berlin.

5.5 Reconstructed view of Priene, later 4th-3rd cent. все. Drawing by Z. Wendel, from W. Hoepfner and E.-L. Schwandner, Haus und Stadt im klassischen Griechenland (Berlin/ Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1994), Fig. 183. Used with permission of Hans Goette and the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Berlin.

|

the agora

The agora was the open area in the heart of the Greek city hosting markets, governmental offices, and meeting chambers, as well as some sanctuaries, shrines, and altars. In looking at a view of the Agora in Athens today from the Areopagos Hill (Figure 5.6), one can see to the left/west the Temple of Hephaistos, which was begun in the 450 s все on a hill bordering the west side of the Agora. The Panathenaic Way, the path of the Panathenaic festival procession from the city gate to the Acropolis, cut diagonally through the center of the Agora; early on there was also a race course for the Panathenaic Games in the central area. Other buildings included fountain houses, offices, mints, jails, and assembly halls. Stones marked the boundaries of the area, and shafts with male genitals and a head of Hermes, called herms, marked entrances. While the modern buildings that bound the Agora today are taller than the houses of ancient times, the contrast between the dense concentration of residential areas and the open space of the Agora is still apparent.

On the right/east is the reconstructed Stoa of Attalos, originally built in the mid-second century and reconstructed 1952-1956 ce. The stoa is the major building type of an agora, and is essentially a colonnaded portico open on one long side. Like the Stoa of Attalos, it can have a second story and/ or a series of rooms along the back for dining, offices, and other functions (see Figure 5.20, page 119). The stoas are rather simple structures, but many had paintings, sculpture, or other objects on display inside them. For example, the Stoa Poikile at the Agora, built in the 460 s, had four monumental paintings showing fallen Troy and battles with Amazons, Persians, and Spartans, along with shields dedicated from the Athenian victory over the Spartans at Sphacteria in 425. It was here in the fourth century that philosophers that we now call Stoics lectured, deriving their name from the building where they gathered.

On the right/east is the reconstructed Stoa of Attalos, originally built in the mid-second century and reconstructed 1952-1956 ce. The stoa is the major building type of an agora, and is essentially a colonnaded portico open on one long side. Like the Stoa of Attalos, it can have a second story and/ or a series of rooms along the back for dining, offices, and other functions (see Figure 5.20, page 119). The stoas are rather simple structures, but many had paintings, sculpture, or other objects on display inside them. For example, the Stoa Poikile at the Agora, built in the 460 s, had four monumental paintings showing fallen Troy and battles with Amazons, Persians, and Spartans, along with shields dedicated from the Athenian victory over the Spartans at Sphacteria in 425. It was here in the fourth century that philosophers that we now call Stoics lectured, deriving their name from the building where they gathered.

|  |  |

The plan of the Agora as it stood around 400 bce shows a concentration of structures on the south and west sides (Figure 5.7). Small stoas and the Altar of the Twelve Gods flank the northwest entrance on both sides of the Panathenaic Way that cuts diagonally through the area on the way to the Acropolis. The Stoa Basileos, or Royal Stoa, is the oldest structure, but suggestions for its dating range from 500 bce to after 480. The Stoa Poikile was built in the 460 s and the Stoa of Zeus in the 420 s. On the hill to the west of the Agora was built the Temple of Hephaistos and below it a small

temple to Apollo. Further south of these were three buildings that served the city council. The round structure, called a tholos, was a dining hall and administrative center for the boule, the council of 500 Athenian citizens chosen to make decisions for a year. The round shape is unusual and how the building was arranged on the interior is not certain. The square structure directly north was built as a bouleuterion, or meeting place of the boule, but was converted into the archive or metroon after a new bouleuterion was built in the 410 s. The new structure was more rectangular in plan and enclosed banked semi-circles of seats for the members of the boule. This small complex was entered by a porch facing the Agora across from the monument of the Eponymous Heroes who represented the twelve tribes of Athens. Once inside the porch, the entrances of the metroon and bouleuterion faced toward each other within the enclosure. On the south side of the Agora were fountain houses, the South Stoa with dining rooms along the back side, and the city mint. The South Stoa was built at the same time as the new bouleuterion and housed the officials in charge of weights and measures, reflecting the commercial importance of the Agora for the city. On the other side of the Panathenaic Way was a square building open in the center with colonnades; this Square Peristyle was a law court built in the fourth century.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1282;

5.1 Reconstructed view of ancient Athens with view of Agora and Acropolis. Drawing by John Travlos. Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations. Top: Acropolis with (left to right) Parthenon (Erechtheion in front); statue of Athena Promachos, Propylaia with Temple of Athena Nike. Lower right: Agora with Panathenaic Way; Stoa Poikile and Stoa Basileos; Temple of Hephaistos. Upper right: Pynx.

5.1 Reconstructed view of ancient Athens with view of Agora and Acropolis. Drawing by John Travlos. Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations. Top: Acropolis with (left to right) Parthenon (Erechtheion in front); statue of Athena Promachos, Propylaia with Temple of Athena Nike. Lower right: Agora with Panathenaic Way; Stoa Poikile and Stoa Basileos; Temple of Hephaistos. Upper right: Pynx.