The first US manned space flight

NASA was cautious about the unknown effect of space flight and was considering additional tests using monkeys, but Yuri Gagarin’s manned orbital flight changed that. Al Shepard had been chosen for the first US manned orbital flight, with Glenn as back‑up. The flight was scheduled for 2 May but was delayed. Glenn:

A weather postponement moved his flight to May 5. I woke up ahead of him in the crew quarters at Hanger S where we both were sleeping, and went to the launch pad to check out the capsule. All the systems were go.

The astronauts had decided that each astronaut would name his own capsule, with a seven added to signify that they were a team no matter who was in the cockpit. Al Shepard named his capsule Freedom 7. Shepard:

At a little after 1 a.m. I got up, shaved and showered and had breakfast with John Glenn and Bill Douglas. John was most kind. He asked me if there was anything he could do, wished me well and went on down to the capsule to get it ready for me. The medical exam and the dressing went according to schedule. There were butterflies in my stomach again, but I did not feel that I was coming apart or that things were getting ahead of me. The adrenalin was pumping, but my blood pressure and pulse rate were not unusually high. A little after 4 a.m., we left the hangar and got started for the pad. Gus and Bill Douglas were with me.

They appeared to be a little behind in the count when we reached the pad. Apparently the crews were taking all the time they could and being extra careful with the preparations. Gordon Cooper, who was stationed in the blockhouse that morning, came in to give me a final weather briefing and to tell me about the exact position of the recovery ships. He said the weathermen were predicting three‑foot waves and 8–10 knot winds in the landing area, which was within our limits. Everything was working fine.

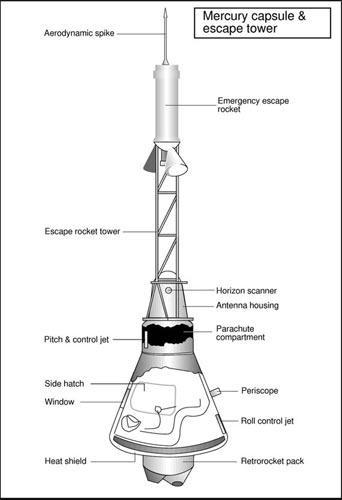

Shortly after 5 a.m., some two hours before lift‑off was scheduled, I asked if I could leave the transfer van. I wanted some extra time to have a word with the launch crews and to check over the Redstone and the capsule, to sort of kick the tyres – the way you do with a new car or an airplane. I realized that I would probably never see that missile again. I really enjoy looking at a bird that is getting ready to go. It’s a lovely sight. The Redstone with the Mercury capsule and escape tower on top of it is a particularly good‑looking combination, long and slender. And this one had a decided air of expectancy about it. It stood there full of lox, venting white clouds and rolling frost down the side. In the glow of the searchlight it was really beautiful.

After admiring the bird, I went up the elevator and walked across the narrow platform to the capsule. On the way up, Bill Douglas solemnly handed me a box of crayons. They came from Sam Beddingfield, he said. Sam is a NASA engineer who has developed a real knack for helping us to relax, and I appreciated the joke. It had to do with another, fictional, astronaut, who discovered just before he was about to be launched on a long and harrowing mission that he had brought along his colouring book to kill time but had forgotten his crayons. The guy refused to get into the capsule until someone went back to the hangar and got him some.

I walked around a bit, talking briefly with Gus again and with John Glenn. I especially wanted to thank John for all the hard work he had done as my backup pilot. Some of the crew looked a little tense up there, but none of the astronauts showed it.

At 5:20 I disconnected the hose which led to my portable air‑conditioner, slipped off the protective galoshes that had covered my boots and squeezed through the hatch. I linked the suit up with the capsule oxygen system, checked the straps which held me tight in the couch, removed the safety pins which kept some of the switches from being pushed or pulled inadvertently and passed them outside.

John had left a little note on the instrument panel, where no one else could see it but me. It read, NO HAND BALL PLAYING IN THIS AREA. I was going to leave it there, but when John saw me laugh behind the visor he grinned and reached in to retrieve it. I guess he remembered that the capsule cameras might pick up that message, and he lost his nerve. No one could speak to me now, face‑to‑face. I had closed the visor and was hooked up with the intercom system. Several people stuck their heads in to take a last‑minute look around, and hands kept reaching in to make little adjustments. Then, at 6:10, the hatch went on and I was alone. I watched as the latches turned to make sure they were tight.

This was the big moment, and I had thought about it a lot. The butterflies were pretty strong now. “OK, Buster,” I said to myself, “you volunteered for this thing. Now it’s up to you to do it.” There was no question in my mind now that we were going – unless some serious malfunction occurred. I had anticipated the nervousness I felt, and I had made plans to counteract it by plunging into my pilot preparations. There were plenty of things to do to keep me busy, and the tension slackened off immediately. I went through all the checklists, checked the radio systems and the gyro switches.

At other places around the Cape at this point, the other astronauts were taking up their positions to back me up in any way they could. Deke Slayton sat at the Capsule Communicator desk in Mercury Control Centre. He would do most of the talking with me during the countdown and flight so that both the lingo and the spirit behind it would be clear and familiar. John and Gus joined Deke as soon as I was firmly locked in and there was nothing more they could do at the pad. Wally and Scott stood by at Patrick Air Force Base, ready to take off in two F‑106jets to chase the Redstone and capsule as far as they could and observe the flight. Gordon stayed in the blockhouse, monitoring the weather and standing by to help put into effect the rescue operations he had worked on which would get me out of the capsule in a hurry if we had an emergency while we were still on the pad. Inside the Mercury Control Centre itself, all the lights were green. All conditions were “Go”. The gantry rolled back at 6:34, and I lay on my back seventy feet above the ground checking the straps and switches and waiting for the countdown to proceed.

I passed some of the time looking through the periscope. I could see clouds up above and people far beneath me on the ground. The view was fascinating – and I had a long, long time to admire it. There were four holds in all, the first at 7:14 when the count stood at T‑15 minutes. A thick, muggy layer of clouds had begun to drift in over the launch site, and a hold was called to give the Control Centre an opportunity to check on the weather. Cape Canaveral sits on a narrow spit of land with the Gulf Stream close by to the east and the Gulf of Mexico only 130 miles to the west. The weather is likely to change rapidly between these two bodies of water. The day can be bright and sunny one minute, cloudy and breezy the next. It is fickle and difficult to keep track of, and in order to follow the capsule and the booster closely, photograph their performance and watch for possible emergencies, the men in the Control Centre require a clear view of the first part of a flight.

The appearance of a small hole in the clouds, however, gave Walt Williams, the Operations Director, enough confidence to carry on, and the meteorologists reported that the clouds would soon blow away and that the sky would be clear again within about thirty minutes. Walt decided to recycle the count – or set it back – to allow for this delay, and he let the mission proceed.

Then another problem cropped up. During the delay for weather, a small inverter located near the top of the Redstone began to overheat. Inverters are used to convert the DC current which comes from the batteries into the AC current required to power some of the systems in the booster. This particular inverter provided 400‑cycle power which was needed to get the missile into operation and off the pad. It had to be replaced. This involved bringing the gantry back into position around the Redstone so that the technicians could get at it, and eighty‑six minutes went by before the Control Centre could resume the count.

I continued to feel fine, however. The doctors could tell how I was doing by looking at their instrument panels and talking it over with me. When the inverter was fixed, the gantry moved away, the cherrypicker manoeuvred its cab back outside the capsule, and the count went along smoothly for twenty‑one minutes before it suddenly stopped again. This time the technicians wanted to doublecheck a computer which would help predict the trajectory of the capsule and its impact point in the recovery area.

I think that my basic metabolism started to speed up along about this point. Everything – pulse rate, carbon dioxide production, blood pressure – began to climb. I suppose that my adrenalin was flowing pretty fast, too. I was not really aware of it at the time. But once or twice I had to warn myself – “You’re building up too fast. Slow down. Relax.” Whenever I though that my heart was palpitating a little, I would try to stop whatever I was doing and look out through the periscope at the pad crews or at the waves along the beach before I went back to work.

The last hold came at T minus 2 minutes 40 seconds. This time the people in the blockhouse were worried about the pressure on the supply of lox in the Redstone which we would need to feed the rocket engines. The pressure on the fuel read a hundred psi too high on the blockhouse gauge, and if this meant resetting the pressure valve inside the booster manually, the mission would have to be scrubbed for at least another forty‑eight hours. Fortunately, the technicians found they were able to bleed off the excess pressure by turning some of the valves by remote control, and the final count resumed at 9:23. I had become slightly and I think understandably impatient at this point. I had been locked inside the capsule for nearly four hours now, and as I listened to the engineers chattering to one another over the radio and debating about whether or not to repair the trouble, I began to get the impression that they were being too cautious just for my sake and might wind up taking too long. It wasn’t really fair of me, but “I’m cooler than you are,” I said into my mike. “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?” They fixed their “little problem” and the orange cherrypicker moved away from the capsule for the last time.

In contrast, after the days of postponement and the holds, the last few minutes leading up to 9:34 a.m. EST (2:43 p.m. GMT) went perfectly. Everyone was prompt in his reports. I could feel that all the training we had gone through with the blockhouse crew and booster crew was really paying off down there. I had no concern at all. I knew how things were supposed to go, and that is how they went. About three minutes before lift‑off, the blockhouse turned off the flow of cooling freon gas – I knew it would shut off anyway at T‑35 seconds when the umbilical fell away. At two minutes before launch, I set the control valves for the suit and cabin temperature, shifted to the voice circuit and had a quick radio check with Deke Slayton at the Capsule Communicator (Cap Com) desk in Mercury Control Centre. I also contacted Chase One and Chase Two Wally Shirra and Scott Carpenter in the chase planes – and heard them loud and clear. They were in the air, ready to take a high‑level look at me as I went past them after the launch.

Electronically speaking, my colleagues were all around me at this moment.

Deke gave me the count at T‑90 seconds and again at T‑60. I had nothing to do just then but maintain my communications, so I rogered both messages. At T‑35 seconds I watched through the periscope as the umbilical which had fed Freon and power into the capsule snapped out and fell away. Then the periscope came in and the little door which protected it in flight closed shut. The red light on my instrument panel went out to signal this event, which was the last critical function the capsule had to perform automatically before we were ready to go. I reported this to Deke, and then I reported the power readings. Both were in a “Go” condition. I heard Deke roger my message, and then I listened as he read the final count: 10‑9‑8‑7… At the count of “5” I put my right hand on the stopwatch button which I had to push at lift‑off to time the flight. I put my left hand on the abort handle which I would move in a hurry only if something went seriously wrong and I had to activate the escape tower.

Just after the count of “Zero”, Deke said “Lift‑off”.

I think I braced myself a bit too much while Deke was giving me the final count. Nobody knew, of course, how much shock and vibration I would really feel when the Redstone took off.

There was no one around who had tried it and could tell me; and we had not heard from Moscow how it felt. I was probably a little too tense. But I was really exhilarated and pleasantly surprised when I answered, “Lift‑off and the clock is started”.

There was a lot less vibration and noise rumble than I had expected. It was extremely smooth – a subtle, gentle, gradual rise off the ground. There was nothing rough or abrupt about it. But there was no question that I was going, either. I could see it on the instruments, hear it on the headphones, feel it, all around me.

It was a strange and exciting sensation. And yet it was so mild and easy – much like the rides we had experienced in our trainers – that it somehow seemed very familiar. I felt as if I had experienced the whole thing before. But nothing could possibly simulate in every detail the real thing that I was going through at that moment, so I tried very hard to figure out all the sensations and to pin them down in my mind in words which I could use later. I knew that the people back on the ground – the engineers, doctors and psychiatrists – would be very curious about how I was affected by each sensation and that they would ask me quite a lot of questions when I got back. I tried to anticipate these questions and have some answers ready.

For the first minute, the ride continued to be very smooth. My main job just then was to keep the people on the ground as relaxed and informed as possible. It was no good for them to have a test pilot up there unless they knew fairly precisely what he was doing, what he saw and how he felt every thirty seconds or so along the way. So I did quite a bit of reporting over the radio about oxygen pressure and fuel consumption and cabin temperature and how the Gs were mounting slowly, just as we had predicted they would. I do not imagine that future spacemen will have to bother quite so much about some of these items. This was the first time, so we were being cautious.

I was scheduled to communicate about something or other for a total of seventy‑eight times during the fifteen minutes that I was up. And I had to manage or at least monitor a total of twenty‑seven major events in the capsule. This kept me rather busy. But we wanted to get our money’s worth when we planned this flight, and we filled the flight plan and the schedule with all the things we wanted to do and learn. We rigged two movie cameras inside the capsule, for example, one of which was focused on the instrument panel to keep a running record of how the system behaved. The other one was aimed at me to see how I reacted. The scientists used the film to compile a chart of all my eye movements, which they related to the position of the instruments I had to watch as each moment and event transpired. On the basis of this data they later moved a couple of the instruments closer together on the panel so that future pilots would not have to move their eyes so often to keep up with things.

One minute after lift‑off the ride did get a little rough. This was where the booster and the capsule passed from sonic to supersonic speed and then immediately went slicing through a zone of maximum dynamic pressure as the forces of speed and air density combined at their peak. The spacecraft started vibrating here. Although my vision was blurred for a few seconds, I had no trouble seeing the instrument panel. I decided not to report this sensation just then. We had known that something like this was going to happen, and if I had sent down a garbled message that it was worse than we had expected and that I was really getting buffeted, I think I might have put everybody on the ground into a state of shock. I did not want to panic anyone into ordering me to leave. And I did not want to leave. So I waited until the vibration stopped and let the Control Centre know indirectly by reporting to Deke that it was “a lot smoother now, a lot smoother”.

The pressure in the cabin held at 5.5 psi, just as it was designed to do. And at two minutes after launch, at an altitude of about 22 miles, the Gs were building up and I was climbing at a speed of 3,200 mph. The ride was fine now, and I made my last transmission before the booster engine cut off: “All Systems are Go.”

The engine cut‑off occurred right on schedule, at 2 minutes 22 seconds after lift‑off. Nothing abrupt happened, just a delicate and gradual dropping off of the thrust as the fuel flow decreased. I heard a roaring noise as the escape tower blew off. I was glad I would not be needing it any longer. I reported all of these events to Deke, and then I heard a noise as the little rockets fired to separate the capsule from the booster. This was a critical point of the flight, both technically and psychologically. I knew that if the capsule got hung up on the booster, I would have quite a different flight, and I had thought about this possibility quite a lot before lift‑off. There is good medical evidence to the effect that I was worried about it again when it was time for the event to take place, for my pulse rate reached its peak here – 138. It started down again right away, however. (About one minute before lift‑off my pulse was 90, and Gus told me later that when he and John Glenn saw this on the medical panel in the Control Centre, they figured that my pulse was a good six points lower than Gus thought his was and eight points lower than John’s.) Right after leaving the booster, the capsule and I went weightless together and I could feel the capsule begin its slow, lazy turnaround to get into position for the rest of the flight. It turned 180°, with the bottom end swinging forward now to take up the heat. It had been facing down and backwards. The periscope went back out again at this point, and I was supposed to do three things in order: (1) take over manual control of the capsule, (2) tell the people downstairs how the controls were working, and (3) take a look outside to see what the view was like.

The capsule was travelling at about 5,000 mph, and up to this point it had been on automatic pilot. I switched over to the manual control stick, and tried out the pitch, yaw and roll axes in that order. Each time I moved the stick, the little jets of hydrogen peroxide rushed through the nozzles on the outside of the capsule and pushed it or twisted it the way I wanted it to go. When the nozzles were on at full blast, I could hear them spurting away over the background noise in my headset. I found out that I could easily use the pitch axis to raise or lower the blunt end of the capsule. This movement was very smooth and precise, just as it had been on our ALFA trainer. I fed the yaw axis, and this manoeuvre worked, too. I could make the capsule twist slightly from left to right and back again, just as I wanted it to. Finally I took over control of the roll motion and I was flying Freedom 7 on my own. This was a big moment for me, for it proved that our control system was sound and that it worked under real space‑flight conditions.

It was now time to go to the periscope. I had been well briefed on what to expect, and I had some idea of the huge variety of colour and land masses and cloud cover which I would see from a hundred miles up. But no one could be briefed well enough to be completely prepared for the astonishing view that I got. My exclamation back to Deke about the “beautiful sight” was completely spontaneous. It was breathtaking. To the south I could see where the cloud cover stopped at about Fort Lauderdale, and that the weather was clear all the way down past the Florida Keys. To the north I could see up the coast of the Carolinas to where the clouds just obscured Cape Hatteras. Across Florida to the west I could spot Lake Okeechobee and Tampa Bay. Because there were some scattered clouds far beneath me I was not able to see some of the Bahamas that I had been briefed to look for. So I shifted to an open area and identified Andros Island and Bimini. The colours around these ocean islands were brilliantly clear, and I could see sharp variations between the blue of deep water and the light green of the shoal areas near the reefs. It was really stunning.

But I did not just admire the view. I found that I could actually use it to help keep the capsule in the proper attitude. By looking through the periscope and focusing down on Cape Canaveral as the zero reference point for the yaw control axis, I discovered that this system would provide a fine backup in case the instruments and the auto‑pilot happened to go out together on some future flight. It was good to know that we could count on handling the capsule this extra way – provided, of course, that we had a clear view and knew exactly what we were looking at. Fortunately, I could look back and see the Cape very clearly. It was a fine reference.

All through this period, the capsule and I remained weightless. And though we had had a lot of free advice on how this would feel – some of it rather dire – the sensation was just what I expected it would be: pleasant and relaxing. It had absolutely no effect on my movements or my efficiency. I was completely comfortable, and it was something of a relief not to feel the pressure and weight of my body against the couch. The ends of my straps floated around a little, and there was some dust drifting around in the cockpit with me. But these were unimportant and peripheral indications that I was at Zero G.

At about 115 miles up – very near the apogee of my flight – Deke Slayton started to give me the countdown for the retro‑firing manoeuvre. This had nothing to do directly with my flight from a technical standpoint. I was established on a ballistic path and there was nothing the retro‑rockets could do to sway me from it. But we would be using these rockets as brakes on the big orbital flights to start the capsule back towards earth. We wanted to try them on my trip just to see how well they worked. We also wanted to test my reactions to them and check on the pilot’s ability to keep the capsule under control as they went off. I used the manual control stick to tilt the blunt end of the capsule up to an angle of 34° above the horizontal – the correct attitude for getting the most out of the retros on an orbital re‑entry. At 5 minutes 14 seconds after launch, the first of the three rockets went off, right on schedule. The other two went off at the prescribed five‑second intervals. There was a small upsetting motion as our speed was reduced, and I was pushed back into the couch a bit by the sudden change in Gs. But each time the capsule started to get pushed out of its proper angle by one of the retros going off I found that I could bring it back again with no trouble at all. I was able to stay on top of the flight by using the manual controls, and this was perhaps the most encouraging product of the entire mission.

Another item on my schedule was to throw a switch to try out an ingenious system for controlling the attitude of the capsule in case the automatic pilot went out of action or we were running low on fuel in the manual control system. We have two different ways of controlling the attitude of the capsule – manually with the control stick, or electrically with the auto‑pilot. In the manual system the movement of the stick activates valves which squirt the hydrogen peroxide fuel out to move the capsule around and correct its attitude. We can control the magnitude of this correction by the amount of pressure we put on the stick. The auto‑pilot works differently. It uses an entirely different set of jets – to give us a backup capability in case one set goes out – and a separate source of fuel. But the automatic jets are not proportional in the force that they exert. This gave the engineers an idea: they created a third possibility, which they call “fly‑by‑wire”, in which the pilot switches off the automatic pilot, then links up his manual stick with the valves that are normally attached to the automatic system. This gives him a new source of fuel to tap if he is running low, and a little more flexibility in managing the controls. The fly‑by‑wire mode seemed fine as far as I was concerned, and another test was checked off the list of things we were out to prove.

We were on our way down now and I waited for the package which holds the retro‑rockets on the bottom of the capsule to jettison and get out of the way before we began our re‑entry. It blew off on schedule and I could feel it go, but the green light which was supposed to report this event failed to light up on the instrument panel. This was our only signal failure of the mission. I pushed the override button and the light turned green as it was supposed to do. This meant that everything was all right.

Now I began to get the capsule ready for re‑entry. Using the control stick, I pointed the blunt end downward at about a 40° angle, and switched the controls back to the auto‑pilot so I could be free to take another look through the periscope. The view was still spectacular. The sky was very dark blue; the clouds were a brilliant white. Between me and the clouds was something murky and hazy which I knew to be the refraction of various layers of the atmosphere through which I would soon be passing.

I fell slightly behind in my schedule at this point. I was at about 230,000 feet when I suddenly noticed a relay come on which had been activated by a device that measures a change in gravity of 0.05G. This was the signal that the re‑entry phase had begun. I had planned to be on manual control when this happened and run off a few more tests with my hand controls before we penetrated too deeply into the atmosphere. But the G forces had built up before I was ready for them, and I was a few seconds behind. I was fairly busy for a moment running around the cockpit with my hands, changing from the auto‑pilot to manual controls, and I managed to get in only a few more corrections in attitude. Then the pressure of the air we were coming into began to overcome the force of the control jets, and it was no longer possible to make the capsule respond. Fortunately, we were in good shape, and I had nothing to worry about so far as the capsule’s attitude was concerned. I knew, however, that the ride down was not one most people would want to try in an amusement park.

In that long plunge back to earth, I was pushed back into the couch with a force of about 11 Gs. This was not as high as the Gs we had all taken during the training programme, and I remember being clear all the way through the re‑entry phase. I was able to report the G level with normal voice procedure, and I never reached the point – as I often had on the centrifuge – where I had to exert the maximum amount of effort to speak or even to breathe. All the way down, as the altimeter spun through mile after mile of descent, I kept grunting out “OK, OK, OK,” just to show them back at the Control Centre how I was doing. The periscope had come back in automatically before the re‑entry started. And there was nothing for me to do now but just sit there, watching the gauges and waiting for the final act to begin.

All through this period of falling the capsule rolled around very slowly in an anti‑clockwise direction, spinning at a rate of about 100 per second around its long axis. This was programmed to even out the heat and it did not bother me. Neither did the sudden rise in temperature as the friction of the air began to build up outside the capsule. The temperature climbed to 1230°F on the outer walls. But it never went above 100° in the cabin or above 82° in my suit. The life support system which Wally had worked – oxygen, water coolers, ventilators and suit – were all working without a hitch. As the G forces began to drop off at about 80,000 feet, I switched back to the auto‑pilot again. By the time I had fallen to 30,000 feet the capsule had slowed down to about 300 mph. I knew from talking to Deke that my trajectory looked good and that Freedom 7 was going to land right in the centre of the recovery area. But there were still several things that had to happen before I could stretch out and take it easy. I began to concentrate now on the parachutes. The periscope jutted out again at about 21,000 feet, and the first thing I saw against the sky as I looked through it was the little drogue chute which had popped out to stabilize my fall. So far, so good. Then, at 15,000 feet, a ventilation valve opened up on schedule to let cool fresh air come into the capsule. The main chute was due to break out at 10,000 feet. If it failed to show up on schedule I could switch to a reserve chute of the same size by pulling a ring near the instrument panel. I must admit that my finger was poised right on that ring as we passed through the 10,000‑foot mark. But I did not have to pull it. Looking through the periscope, I could see the antenna canister blow free on top of the capsule. Then the drogue chute went floating away, pulling the canister behind it. The canister, in turn, pulled out the bag which held the main chute and pulled it free. And then, all of a sudden, after this beautiful sequence, there it was – the main chute stretching out long and thin. Four seconds later the reefing broke free and the huge orange and white canopy blossomed out above me. It looked wonderful right from the beginning, letting me down at just the right speed.

The water landing was all that remained now, and I started getting set for it. I opened the visor in the helmet and disconnected the hose that keeps the visor sealed when the suit is pressurized. I took off my knee straps and released the strap that went across my chest. The capsule was swaying gently back and forth under the chute. I knew that the people back in the Control Centre were anxious about all this, so I sent two messages – one through a voice relay airplane which was hovering around nearby, and the other through a telemetry ship which was parked in the recovery area down below. Both messages read the same: “All OK.”

At about a thousand feet I looked out through the porthole and saw the water coming up towards me. I braced myself in the couch for the impact, but it was not at all bad. It was a little abrupt, but no more severe than a jolt a pilot gets when he is launched off the catapult of an aircraft‑carrier. The spacecraft hit and then it flopped over on its side so that I was leaning over on my right side in the couch. One porthole was completely under water. I hit the switch to kick the reserve parachute loose. This would take some of the weight off the top of the capsule and help it right itself. The same switch started a sequence which deployed a radio antenna to help me signal position. I could see the yellow dye marker colouring the water through the other porthole. This meant that the other recovery aids were working. Slowly but steadily the capsule began to right itself. As soon as I knew the radio antenna was out of the water I sent off a message saying that I was fine.

I took off my lap belt and loosened my helmet so I could take it off quickly when I went out the door. And I had just started to make a final reading on all of the instruments when the carrier’s helicopter pilot called me. I had already told him that I was in good shape, but he seemed in a hurry to get me out. I heard the shepherd’s hook catch hold of the top of the capsule, and then the pilot called again.

“OK,” he said, “you’ve got two minutes to come out.” I decided he knew what he was doing and that following his instruction was perhaps more important than taking those extra readings. I could still see water out of the window, and I wanted to avoid getting any of it in the capsule, so I called the pilot back and asked him if he would lift the capsule a little higher. He obligingly hoisted it up a foot or two. I told him then that I would be out in thirty seconds.

I took off my helmet, disconnected the communications wiring which linked me to the radio set and took a last look around the capsule. Then I opened the door and crawled to a sitting position on the sill. The pilot lowered the horse‑collar sling; I grapped it, slipped it on and then began the slow ride up into the helicopter. I felt relieved and happy. I knew I had done a pretty good job. The Mercury flight systems had worked out even better than we had thought they would. And we had put on a good demonstration of our capability right out in the open where the whole world could watch us taking our chances.

Glenn described Shepard’s reaction:

Al’s reaction was exuberance and satisfaction. He talked about his five minutes of weightlessness as painless and pleasant. He’d had no unusual sensations, was elated at being able to control the capsule’s attitude, and was only sorry the flight hadn’t lasted longer.

Al’s flight was greeted as a triumph around the world because it had been visible. The world had learned of Gagarin’s flight from Nikita Khrushchev. It had learned of Al’s by watching it on live television and listening to it on the radio. That openness was as significant a triumph in the Cold War battle of ideologies as Gagarin’s flight had been scientifically.

Kennedy used the momentum of Al’s flight boldly. Now that men on both sides of the Iron Curtain had entered space one way or another, the president leapfrogged to the next great step. He went to Congress on May 25 and in a memorable speech urged it to plunge into the space race with both feet. He said, “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind or more important for the long‑range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 1103;