Glenn’s orbital flight

More sub‑orbital flights were scheduled but on 6 August 1961 the Russian cosmonaut Major Yuri Titov made a 17‑orbit flight which lasted 25 hours. NASA was hoping to put a man into orbit before the end of the year and this time it would be Glenn. He decribed the preparations:

Atlas testing moved into its final phase. A September 13 Atlas launch, MA‑4, carried a dummy astronaut into orbit and back after circling Earth once, and the capsule landed on target in the Atlantic. At that point the system seemed ready. The Atlas had been strengthened not only by the belly band but with the use of thicker metal near the top. But Bob Gilruth and Hugh Dryden, NASA’s deputy administrator, wanted to send a chimp into orbit before risking a man.

This time the chimp was named Enos, and he went up on November 29. Like Ham, he had been conditioned to pull certain levers in the spacecraft according to signals flashing in front of him. Like Ham’s, his flight was not altogether perfect. The capsule’s attitude control let it roll 45 degrees before the hydrogen peroxide thrusters corrected it. Controllers brought it down in the Pacific after two orbits and about three hours.

When Enos was picked up he had freed an arm from its restraint, gotten inside his chest harness, and pulled off the biosensors that the doctors had attached to record his respiration, heartbeat, pulse, and blood pressure. He also had ripped out the inflated urinary catheter they had implanted, which sent his heart rate soaring during the flight. It made you cringe to think of it.

Nevertheless, Enos’s flight was a success and he appeared unfazed at the postflight news conference with Bob and Walt Williams, Project Mercury’s director of operations. All the attention was on the chimpanzee when one of the reporters asked who would follow him into orbit.

Bob gave the world the news I’d learned just a few weeks earlier, when he had called us all into his office at Langley to tell us who would make the next flight. I had been elated when, at last, I heard that I would be the primary pilot. This time I was on the receiving end of congratulations from a group of disappointed fellow astronauts. Now, as the reporters waited with their pencils poised and cameras running, Bob said, “John Glenn will make the next flight. Scott Carpenter will be his backup.”

The launch date was originally set for 16 January but due to bad weather it was postponed until 23 January. Glenn:

I woke up at about one‑thirty on the morning of February 20, 1962. It was the eleventh date that had been scheduled for the flight. I lay there and went through flight procedures, and tried not to think about an eleventh postponement. Bill Douglas came in a little after two and leaned on my bunk and talked. He said the weather was fifty‑fifty and that Scott had already been up to check out the capsule and called to say it was ready to go. I showered, shaved, and wore a bathrobe while I ate the now‑familiar low‑residue breakfast with Bill, Walt Williams, NASA’s preflight operations director, Merritt Preston, and Deke Slayton who was scheduled to make the next flight.

Bill gave me a once‑over with a stethoscope and shone a light into my eyes, ears, and throat. “You’re fit to go,” he said and started to attach the biosensors. Joe Schmitt laid out the pressure suit’s various components, the suit itself, the helmet, and the gloves, which contained fingertip flashlights for reading the instruments when I orbited from day into night. I put on the urine collection device that was a version of the one Gus and I had devised the night before his flight, then the heavy mesh underliner with its two layers separated by wire coils that allowed air to circulate. I put the silver suit on – one leg at a time, like everybody else, I reminded myself. In a pocket in addition to the small pins I had designed, I carried five small silk American flags. I planned to present them to the President, the commandant of the Marine Corps, the Smithsonian Institution, and Dave and Lyn.

Joe gave the suit a pressure check, and Bill ran a hose into his fish tank to check the purity of the air supply; dead fish would mean bad air. I was putting on the silver boots and the dust covers that would come off once I was through the dust‑free “white room” outside the capsule at the top of the gantry when I said casually, “Bill, did you know a couple of those fish are floating belly‑up?”

“What?” He rushed over to the tank and looked inside before he realized I was kidding.

I put my white helmet on, left Hangar S carrying the portable air blower; waved at the technicians, and got into the transfer van. In the van, I looked over weather data and flight plans. About two hundred technicians were gathered around Launch Complex 14 when I got out of the van. Searchlights lit the silvery Atlas much as they had the night we had watched it blow to pieces. I thought instead of the successful tests since then. Clouds rolled overhead in the predawn light. It was six o’clock when I rode the elevator up the gantry. Scott was waiting in the white room to help me into the capsule. In addition to white coveralls and dust covers on your shoes, you had to wear a paper cap in the white room. It made the highly trained capsule insertion crew look like drugstore soda jerks. I bantered with Guenter Wendt, the “pad führer” who ran the white room with precision, before wriggling feet first into the capsule and settling in to await the countdown.

The original launch time passed as a weather hold delayed the countdown. Then a microphone bracket in my helmet broke. Joe Schmitt fixed that, I said goodbye to everybody, and the crew bolted the hatch into place. They sheared a bolt in the process, so they unbolted the hatch, replaced the bolt, and secured it back into place. That took another forty minutes. I still didn’t believe I would actually go.

I heard a steady stream of conversation on my helmet headset, weather and technical details passed between the blockhouse and the control center in NASA’s technical patois. A voice said the clouds were thinning. Up and down the beaches and on roadsides around the Cape, I knew thousands of people were assembled for the launch. Some of them had been there for a month. The countdown would resume, then stop. I just waited. Then the gantry pulled away, and I could see patches of blue sky through the window. The steady patter of blockhouse communications continued. Scott, in the blockhouse, made a call and let me know he had patched me through to Arlington so I could talk privately with Annie. “How are you doing?” I said.

“We’re fine. How are you doing?”

“Well, I’m all strapped in. The gantry’s back. If we can just get a break on the weather, it looks like I might finally go. How are the kids?”

“They’re right here.” I spoke first to Lyn, then Dave. They told me they were watching all three networks and the preparations looked exciting. Then Annie came back on the line.

“Hey, honey, don’t be scared,” I said. “Remember; I’m just going down to the corner store to get a pack of gum.”

Her breath caught. “Don’t be long,” she said.

“I’ll talk to you after I land this afternoon.” It was all I could do to add the words, “I love you.” I heard her say, “I love you too.” I was glad nobody could see my eyes.

In a mirror near the capsule window, I could see the blockhouse and back across the Cape. The periscope gave me a view out over the Atlantic. It was turning into a fine day. I felt a little bit like the way I had felt going into combat. There you are, ready to go; you know all the procedures and there’s nothing left to do but just do it. People have always asked if I was afraid. I wasn’t. Constructive apprehension is more like it. I was keyed up and alert to everything that was going on, and I had full knowledge of the situation – the best antidote to fear. Besides, this was the fourth time I had suited up, and I still had trouble believing I would actually take off.

Pipes whined and creaked below me; the booster shook and thumped when the crew gimballed the engines. I clearly was sitting on a huge, complex machine. We had joked that we were riding into space on a collection of parts supplied by the lowest bidder on a government contract, and I could hear them all.

At T minus thirty‑five minutes, I heard the order to top off the lox tanks. Instantly the voices in my headset vibrated with a new excitement. We’d never gotten this far before. Topping off the lox tanks was a landmark in the countdown. The crew had begun to catch “go fever.”

There was a hold at twenty‑two minutes when a lox valve stuck, and another at six minutes to solve an electrical power failure at the tracking station in Bermuda. Then the minutes dwindled into seconds.

At eighteen seconds the countdown switched to automatic, and I thought for the first time that it was going to happen. At four seconds I felt rather than heard the rocket engines stir to life sixty‑five feet below me. The hold‑down clamps released with a thud. The count reached zero at 9:47 am.

My earphones didn’t carry Scott’s parting message: “Godspeed, John Glenn.” Tom O’Malley, General Dynamics’ test director, added, “May the good Lord ride with you all the way.”

Liftoff was slow. The Atlas’s 367,000 pounds of thrust were barely enough to overcome its 125 ton weight. I wasn’t really off until the forty‑two‑inch umbilical cord that took electrical connections to the base of the rocket pulled loose. That was my last connection with Earth. It took the two boosters and the sustainer engine three seconds of fire and thunder to lift the thing that far. From where I sat the rise seemed ponderous and stately, as if the rocket were an elephant trying to become a ballerina. Then the mission elapsed‑time clock on the cockpit panel ticked into life and I could report, “The clock is operating. We’re under way.”

I could hardly believe it. Finally!

The rocket rolled and headed slightly north of east. At thirteen seconds I felt a little shudder. “A little bumpy along about here,” I reported. The G forces started to build up. The engines burned fuel at an enormous rate, one ton a second, more in the first minute than a jet airliner flying coast to coast, and as the fuel was consumed the rocket grew lighter and rose faster. At forty‑eight seconds I began to feel the vibration associated with high Q, the worst seconds of aerodynamic stress, when the capsule was pushing through air resistance amounting to almost a thousand pounds per square foot. The shaking got worse, then smoothed out at 1:12, and I felt the relief of knowing that I was through max Q, the part of the launch where the rocket was most likely to blow.

At 2:09 the booster engines cut off and fell away. I was miles high and forty‑five miles from the Cape. The rocket pitched forward for the few seconds it took for the escape tower’s jettison rocket to fire, taking the half‑ton tower away from the capsule. The G forces fell to just over one. Then the Atlas pitched up again and, driven by the sustainer engine and the two smaller vernier engines, made course corrections, resumed its acceleration toward a top speed of 17,545 miles per hour in the ever‑thinning air. Another hurdle passed. Another instant of relief.

Pilots gear their moments of greatest attention to the times when flight conditions change. When you get through them, you’re glad for a fraction of a second, and then you think about the next thing you have to do.

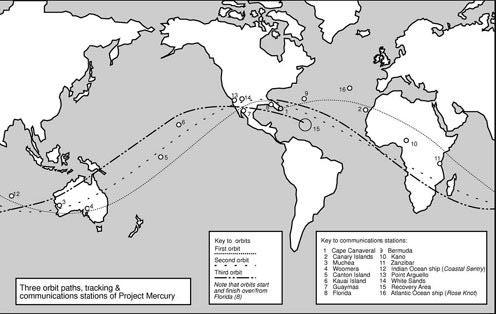

The Gs built again, pushing me back into the couch. The sky looked dark outside the window. Following the flight plan, I repeated the fuel, oxygen, cabin pressure, and battery readings from the dials in front of me in the tiny cabin. The arc of the flight was taking me out over Bermuda. “Cape is go and I am go. Capsule is in good shape,” I reported.

“Roger. Twenty seconds to SECO.” That was Al Shephard on the capsule communicator’s microphone at mission control, warning me that the next crucial moment – sustainer engine cutoff – was seconds away.

Five minutes into the flight, if all went well, I would achieve orbital speed, hit zero G, and, if the angle of ascent was right, be inserted into orbit at a height of about a hundred miles. The sustainer and vernier engines would cut off, the capsule‑to‑rocket clamp would release, the posigrade rockets would fire to separate Friendship 7 from the Atlas.

It happened as programmed. The weight and fuel tolerances were so tight that the engines had less than three seconds’ worth of fuel remaining when I hit that keyhole in the sky. Suddenly I was no longer pushed back against the seat but had a momentary sensation of tumbling forward.

“Zero G and I feel fine,” I said exultantly. “Capsule turning around.” Through the window I could see the curve of Earth and its thin film of atmosphere. “Oh,” I exclaimed, “that view is tremendous!”

The capsule continued to turn until it reached its normal orbital attitude, blunt end forward. It was flying east and I looked back to the west. There was the spent tube of the Atlas making slow pirouettes behind me, sunlight glinting from its metal skin. It was beautiful, too.

Al’s voice came in my earphones. “Roger, Seven. You have a go, at least seven orbits.”

That was the best possible news. I was higher than space flight when I heard that. The mission was planned for three orbits, but it meant that I could go for at least seven if I had to. The first set of hurdles was behind me. I loosened the shoulder straps and seat belt that held me to the couch, and prepared to go to work.

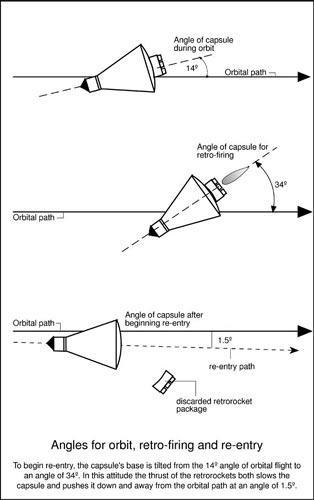

The capsule was pitched thirty‑four degrees from horizontal in its normal orbital attitude, so I could see back across the ocean to the western horizon. The periscope had automatically deployed and gave me a view to the east in the direction of the capsule’s flight. The worldwide tracking network switched into gear. I talked to Gus, who was the capsule communicator, or capcom, at the Bermuda station. “This is very comfortable at zero G. I have nothing but a very fine feeling. It just feels very normal and very good.”

Over the Canary Islands, almost to the west coast of America, I could still see the Atlas turning behind me. It was a mile away now, and slightly below me, losing ground because I was in a slightly higher orbit. I did a quick check of the capsule’s attitude controls in case I had to make an emergency reentry. Pitch, roll, and yaw were primarily governed by an automatic system in which gyroscopes and sensors sent electrical signals to eighteen one‑and five‑pound hydrogen peroxide thrusters arrayed around the capsule. In “fly‑by‑wire” mode, I could use the three‑axis control stick to override the automatic system using its same electrical connections. A fully manual system provided redundancy in a variety of attitude control modes. All three systems worked perfectly.

Friendship 7 crossed the African coast twelve minutes after liftoff, a fast transatlantic flight. I reached for the equipment pouch fixed just under the hatch. It used a new invention, a system of nylon hooks and loops called Velcro. I opened the pouch and a toy mouse floated into my vision. It was gray felt, with pink ears and a long tail that was tied to keep it from floating out of reach. I laughed at the mouse which was Al’s joke, a reference to one of comedian Bill Dana’s characters, who always felt sorry for the experimental mice that had gone into space in rocket nose cones.

I reached around the mouse and took out the Minolta camera. Floating under my loosened straps, I found that I had adapted to weightlessness immediately. When I needed both hands, I just let go of the camera and it floated there in front of me. I didn’t have to think about it. It felt natural.

Telemetry was sending signals to the ground about my condition and the condition of the capsule. The capcom at the Canary Islands station asked for a blood pressure check, and I pumped the cuff on my left arm. The EKG and biosensors were sending signals about my heart pulse, and respiration, and the ever‑present rectal thermometer was reporting my body temperature. At 18:41 I reported, (“Have a beautiful view of the African coast, both in the scope and out the window. Out the window is the best view by far.”

“Your medical status is green,” Canary capcom reported. I asked for my blood pressure. The capcom reported back that it was 120 over 80, normal.

I took pictures of clouds over the Canaries. At twenty‑one minutes, over the Sahara Desert, I aimed the camera at massive dust storms swirling the desert sand.

The tracking station at Kano, Nigeria, came on. I was forty seconds behind on my checklist of tasks, and went to fly‑by‑wire to check the capsule’s yaw control again. The thrusters moved the capsule easily, and I reported at 26.34, “Attitudes all well within limits. I have no problem holding attitude with fly‑by‑wire at all. Very easy.”

Over Zanzibar off the East African coast, the site of the fourth tracking station, I pulled thirty times on the bungee cord attached below the control panel. I had done this on the ground, and my reaction was the same: it made me tired and increased my heart rate temporarily – I pumped the blood pressure cuff again for the flight surgeon on the ground. I read the vision chart over the instrument panel with no problem, countering the doctors’ fear that the eyeballs would change shape in weightlessness and impair vision. Head movements caused no sensation, indicating that zero G didn’t attack the balance mechanism of the inner ear. I could reach and easily touch any spot I wanted to, another test of the response to weightlessness. The ease of the adjustment continued to surprise me.

The Zanzibar flight surgeon reported that my blood pressure and pulse had returned to normal after my exertion with the bungee cord. “Everything on the dials indicates excellent aeromedical status,” he said. This was what we had expected from doing similar tests on the procedures trainer.

Flying backward over the Indian Ocean, I began to fly out of daylight. I was now about forty minutes into the flight nearing the 150‑mile apogee, the highest point, of my orbital track. Moving away from the sun at 17,500 miles an hour – almost eighteen times Earth’s rotational speed – sped the sunset.

This was something I had been looking forward to, a sunset in space. All my life I have remembered particularly beautiful sunrises or sunsets in the Padfic islands in World War II; the glow in the haze layer in northern China; the two thunderheads out over the Atlantic with the sun silhouetting them the morning of Gus’s launch. I’ve mentally collected them, as an art collector remembers visits to a gallery full of Picassos, Michelangelos, or Rembrandts. Wonderful as man‑made art may be, it cannot compare in my mind to sunsets and sunrises, God’s masterpieces. Here on Earth we see the beautiful reds, oranges, and yellows with a luminous quality that no film can fully capture. What would it be like in space?

It was even more spectacular than I imagined, and different in that the sunlight coming through the prism of Earth’s atmosphere seemed to break out the whole spectrum, not just the colors at the red end but the blues, indigos, and violets at the other. It made spectacular an understatement for the few seconds view. From my orbiting front porch, the setting sun that would have lingered during a long earthly twilight sank eighteen times as fast. The sun was fully round and as white as a brilliant arc light, and then it swiftly disappeared and seemed to melt into a long thin line of rainbow‑brilliant radiance along the curve of the horizon.

I added my first sunset from space to my collection.

I reported to the capcom aboard the ship, the Ocean Sentry , in the Indian Ocean that was my fifth tracking link, “The sunset was beautiful. I still have a brilliant blue band clear across the horizon, almost covering the whole window.

The sky above is absolutely black, completely black. I can see stars up above.”

Flying on, I could see the night horizon, the roundness of the darkened Earth, and the light of the moon on the clouds below. I needed the periscope to see the moon coming up behind me. I began to search the sky for constellations.

Gordo Cooper’s familiar voice came over the headset as Friendship 7 neared Australia. He was the capcom at the station at Muchea, on the west coast just north of Perth. “That sure was a short day,” I told him.

“Say again, Friendship Seven.”

“That was about the shortest day I’ve ever run into.”

“Kinda passes rapidly, huh?”

“Yes, sir.”

I spotted the Pleiades, a cluster of seven stars. Gordo asked me for a blood pressure reading, and I pumped the cuff again. He told me to look for lights, and I reported, “I see the outline of a town, and a very bright light just to the south of it?” The elapsed‑time clock read 54:39. It was midnight on the west coast of Australia.

“Perth and Rockingham, you’re seeing there,” Gordo told me.

“Roger. The lights show up very well, and thank everybody for turning them on, will you?”

“We sure will, John.”

The capcom at Woomera, in south‑central Australia, radioed that my blood pressure was 126over 90. I replied that I still felt fine, with no vision problems and no nausea or vertigo from the head movements I made periodically.

The experiments continued. Over the next tracking station, on a tiny coral atoll called Canton Island, midway between Australia and Hawaii, I lifted the visor of my helmet and ate for the first time, squeezing some apple sauce from a toothpaste‑like tube into my mouth to see if weightlessness interfered with swallowing. It didn’t.

It was all so new. An hour and fourteen minutes into the flight, I was approaching day again. I didn’t have time to reflect on the magnitude of my experience, only to record its components as I reeled off the readings and performed the tests. The capcom on Canton Island helped me put it in perspective after I reported seeing through the periscope “the brilliant blue horizon coming up behind me, approaching sunrise.”

“Roger, Friendship Seven. You are very lucky.”

“You’re right. Man, this is beautiful.”

The sun rose as quickly as it had set. Suddenly there it was, a brilliant red in my view through the periscope. It was blinding, and I added a dark filter to the clear lens so I could watch it. Suddenly I saw around the capsule a huge field of particles that looked like tiny yellow stars that seemed to travel with the capsule, but more slowly. There were thousands of them, like swirling fireflies. I talked into the cockpit recorder about this mysterious phenomenon as I flew out of range of Canton Island and into a dead zone before the station at Guaymas, Mexico, on the Gulf of California, picked me up. We thought we had foreseen everything, but this was entirely new. I tried to describe them again, but Guaymas seemed interested only in giving me the retro sequence time, the precise moment the capsule’s retro‑rockets would have to be fired in case I had to come down after one orbit.

Changing film in the camera, I discovered a pitfall of weightlessness when I inadvertently batted a canister of film out of sight behind the instrument panel. I waited a few seconds for it to drop into view and then realised that it wouldn’t.

I was an hour and a half into the flight, and in range of the station at Point Arguello, California, where Wally Schirra was acting as capcom. I had just picked him up and was looking for a sight of land beneath the clouds when the capsule drifted out of yaw limits about twenty degrees to the right. One of the large thrusters kicked it back. It swung to the left until it triggered the opposite large thruster; which brought it back to the right again. I went to fly‑by‑wire and oriented the capsule manually.

The “fireflies” diminished in number as I flew east into brighter sunlight. I switched back to automatic attitude control. The capsule swung to the right again, and I switched back to manual. I picked up Al at the Cape and gave him my diagnosis. The one‑pound thruster to correct outward drift was out, so the drift continued until the five‑pound thruster activated, and it pushed the capsule too far into left yaw, activating the larger thruster there. The thrusters were setting up a back‑and‑forth cycle that, if it persisted, would diminish their fuel supply and maybe jeopardize the mission.

“Roger, Seven, we concur. Recommending you remain fly‑by‑wire.”

“Roger. Remaining fly‑by‑wire.”

Al said that President Kennedy would be talking to me by way of a radio hookup, but it didn’t come through and Al asked for my detailed thirty‑minute report instead. I reported at 1:36:54 that controlling the capsule manually was smooth and easy, and the fuses and switches were all normal. I paused to ask about the presidential hookup. “Are we in communication yet? Over.”

“Say again, Seven.”

“Roger. I’ll be out of communication fairly soon. I thought if the other call was in, I would stop the check. Over.”

“Not as yet. We’ll get you next time.”

“Roger. Continuing report.” I ran through conditions in the cabin and added, “Only really one unusual thing so far besides ASCS [the automatic attitude control] trouble were the little particles, luminous particles around the capsule, just thousands of them right at sunrise over the Pacific. Over.”

“Roger, Seven, we have all that. Looks like you’re in good shape. Remain on fly‑by‑wire for the moment.”

As the second orbit began, I thought I could see a long wake from a recovery ship in the Atlantic. One of the tracking stations was aboard the ship Rose Knot , off the West African coast at the equator. I moved into its range and reported a reversal of the thruster problem. Now I seemed to have no low right thrust in yaw, to correct leftward drift. I performed a set maneuver, turning the capsule 180 degrees in yaw so that I was flying facing forward. “I like this attitude very much, so you can see where you’re going,” I radioed. I also reported seeing a loose bolt floating inside the periscope.

I passed the two‑hour mark of the flight over Africa, with the capsule back in its original attitude. The second sunset was as brilliant as the first, the light again departing in a band of rainbow colors that extended on each side of the sunfall. Over Zanzibar, my eyeballs still held their shape; I reported, “I have no problem reading the charts, no problem with astigmatism at all. I am having no trouble at all holding attitudes, either. I’m still on fly‑by‑wire.”

The Coastal Sentry , in the Indian Ocean, relayed a strange message from mission control. “Keep your landing bag switch in off position. Landing bag switch in off position. Over.”

I glanced at the switch. It was off.

I returned to ASCS to see if the system was working. But now the capsule began to have pitch and roll as well as yaw problems in its automatic setting. The gyroscope‑governed instruments showed the capsule was flying in its proper attitude, but what my eyes told me disagreed. The Indian Ocean capcom asked if I had noticed any constellations yet.

“This is Friendship Seven. Negative. I have some problems here with ASCS. My attitudes are not matching what I see out the window. I’ve been paying pretty close attention to that. I’ve not been identifying stars.”

The ASCS fuel supply was down to 60 percent, so I cut it off and started flying manually. Gordo, in Muchea, asked me to confirm that the landing bag switch was off.

“That is affirmative. Landing bag switch is in the center off position.”

“You haven’t had any banging noises or anything of this type at higher rates?” He meant the rate of movement in roll, pitch, or yaw.

“Negative.”

“They wanted this answer.”

I flew on, feeling no vertigo or nausea or other ill effects from weightlessness, being able to read the same lines on the eye chart I could at the beginning. I pumped the blood pressure cuff for another check and gave the readings in the regular half‑hour reports. Flying the capsule with the one‑stick hand controller was taking most of my attention. The second dawn produced another flurry of the luminescent partides. “They’re all over the sky,” I reported. “Way out I can see them, as far as I can see in each direction, almost.”

The Canton Island capcom ignored the particles and asked me to report any sensations I was feeling from weightlessness. Then came an unprompted transmission.

“We also have no indication that your landing bag might be deployed. Over.”

I had a prickle of suspicion. “Roger. Did someone report landing bag could be down? Over.”

“Negative. We have a request to monitor this and ask if you heard any flapping when you had high capsule rates.”

It suddenly made sense. They were trying to figure out where the particles had come from. I was convinced they weren’t coming from the capsule. They were all over the sky.

Daylight again. I had caged and reset the gyros during the night, and did it again in the light, but they were still off. I reported to the capcom in Hawaii that the instruments indicated a twenty‑degree right roll when I was lined up with the horizon.

“Do you consider yourself go for the next orbit?”

“That is affirmative. I am go for the next orbit.” There was no question in my mind about that. I could control the capsule easily, and I was confident that even with faulty gyroscopes I could align the capsule for its proper retrofire angle by using the stars and the horizon.

I flew over the Cape into the third orbit. The gyros seemed to have corrected themselves. Al radioed a recommendation that I allow the capsule to drift on manual control to conserve fuel.

The sky was clear over the Atlantic. Gus came on from Bermuda and I radioed, “I have the Cape in sight down there. It looks real fine from up here.”

“Rog. Rog.”

“As you know.”

“Yea, verily, Sonny.”

I could see not only the Cape, but the entire state of Florida. The eastern seaboard was bathed in sunshine, and I could see as far back as the Mississippi Delta. It was also clear over the recovery area to the south. “Looks like we’ll have no problem on recovery,” I said.

“Very good. We’ll see you in Grand Turk.”

Gus faded as I let the capsule drift around again 180 degrees, so that I was facing forward for the second time. It was more satisfying, and felt more like real flying. I still felt good physically, with none of the suspected ill effects. When I turned the capsule back to orbit attitude, the problem with the gyros reappeared, indicating more pitch, roll, and yaw than my view of the horizon indicated. The Zanzibar capcom asked why.

“That’s a good question. I wish I knew, too.”

I saw my third sunset of the day, and flew over clouds with lightning pulsing and rippling inside them. The lightning flashes looked like lightbulbs pulsing inside a veil of cotton gauze. Over the Indian Ocean, I went back to full manual control because the automatic with manual backup was using too much of the thrusters’ supply of fuel. There had to be enough left when the time came to achieve the proper reentry attitude. I pitched the capsule up for a look at the night stars. The constellation Orion was right in the middle of the window, and I could hold my attitude by watching it.

Over Muchea, approaching four hours since liftoff, I told Gordo, “I want you to send a message to the commandant, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington. Tell him I have my four hours required flight time in for the month and request flight chit be established for me. Over.”

“Roger. Will do. Think they’ll pay it?”

“I don’t know. Gonna find out.”

“Roger. Is this flying time or rocket time?”

“Lighter than air, buddy.” Gordo would appreciate that. He and Deke had led the charge for getting us some flying time while we were training.

I turned the capsule around again so I could face the sunrise. The light revealed a new cloud of the bright partides, and I was still convinced they weren’t coming from the capsule. The flight surgeon at Woomera suggested that I eat again. But I had been paying too much attention to the attitude control, and now I was concerned about lining up the spacecraft for reentry. This was the next set of hurdles, another crucial change in flight conditions that would require every ounce of my attention. I was over Hawaii when the capcom there said, “Friendship Seven, we have been reading an indication on the ground of segment fifty‑one, which is landing bag deploy. We suggest this is as an erroneous signal. However, Cape would like you to check this by putting the landing bag switch in auto position and see if you get a light Do you concur with this? Over.”

Now, for the first time, I knew why they had been asking about the landing bag. They did think it might have been activated, meaning that the heat shield that would protect the capsule from the searing heat of reentry was unlatched. Nothing was flapping around. The package of retro‑rockets that would slow the capsule for reentry was strapped over the heat shield. But it would jettison, and what then? If the heat shield dropped out of place, I could be incinerated on reentry, and this was the first confirmation of that possibility. I thought it over for a few seconds. If the green light came on, we’d know that the bag had accidentally deployed. But if it hadn’t, and there was something wrong with the circuits, flipping the switch to automatic might create the disaster we had feared. “Okay,” I reluctantly concurred, “if that’s what they recommend, we’ll go ahead and try it.”

I reached up and flipped the switch to auto. No light. I quickly switched it back to off. They hadn’t been trying to relate the particles to the landing bag at all.

“Roger, that’s fine,” the Hawaii capcom said. “In this case, we’ll go ahead, and the reentry sequence will be normal.”

The seconds ticked down toward the retro‑firing sequence. I passed out of contact with Hawaii and into Wally Shirra’s range at Point Arguello. I was flying backward again, the blunt end of the capsule facing forward, manually backing up the erratic automatic system. The retro warning light came on. A few seconds before the rockets fired, Wally said, “John, leave your retro pack on through your pass over Texas. Do you read?”

“Roger.”

I moved the hand controller and brought the capsule to the proper attitude. The first retro‑rocket fired on time at 4:33:07. Every second off would make a five‑mile difference in the landing spot. The braking effect on the capsule was dramatic. “It feels like I’m going back toward Hawaii,” I radioed.

“Don’t do that,” Wally joked. “You want to go to the East Coast.”

The second rocket fired five seconds later, the third five seconds after that. They each fired for about twelve seconds, combining to slow the capsule about five hundred feet per second, a little over 330 miles per hour, not much but enough to drop it below orbital speed. Normally the exhausted rocket package would be jettisoned to burn as it fell into the atmosphere, but Wally repeated, “Keep your retro pack on until you pass Texas.”

“That’s affirmative.”

“Pretty good‑looking flight from what we’ve seen,” Wally said.

“Roger. Everything went pretty good except for this ASCS problem.”

“It looked like your attitude held pretty well. Did you have to back it up at all?”

“Oh, yes, quite a bit. Yeah, I had a lot of trouble with it.”

“Good enough for government work from down here.”

“Yes, sir, it looks good, Wally. We’ll see you back East.”

“Rog.”

I gave a fast readout of the gauges and asked Wally, “Do you have a time for going to jettison retro? Over.”

“Texas will give you that message. Over.”

Wally and I kept chatting like a couple of tourists ex changing travel notes. “This is Friendship Seven. Can see El Centro and the Imperial Valley, Salton Sea very clear.”

“It should be pretty green. We’ve had a lot of rain down here.”

The automatic yaw control kept banging the capsule back and forth, so I switched back to manual in all three axes. The capcom at Corpus Christi, Texas, came on and said, “We are recommending that you leave the retro package on through the entire reentry. This means you will have to override the point‑zero‑five‑G switch [this sensed atmospheric resistance and started the capsule’s reentry program], which is expected to occur at oh four forty‑three fifty‑eight. This also means that you will have to manually retract the scope. Do you read?”

The mission clock read 4:38:47. My suspicions flamed back into life. There was only one reason to leave the retro pack on, and that was because they still thought the heat shield could be loose. But still, nobody would say so.

“This is Friendship Seven. What is the reason for this? Do you have any reason? Over.”

“Not at this time. This is the judgment of Cape flight.”

“Roger. Say again your instructions, please. Over.”

The capcom ran it through again.

“Roger, understand. I will have to make a manual zero‑five‑G entry when it occurs, and bring the scope in manually.”

Metal straps hugged the retro pack against the heat shield. Without jettisoning the pack, the straps and then the pack would burn up as the capsule plunged into the friction the atmosphere. I guessed they thought that by the time that happened, the force of the thickening air would hold the heat shield against the capsule. If it didn’t, Friendship and I would burn to nothing. I knew this without anybody’s telling me, but I was irritated by the cat‑and‑mouse game they were playing with the information. There was nothing to do but line up the capsule for reentry.

I picked up Al’s voice from the Cape. He said, “Recommend you go to reentry attitude and retract the scope manually at this time.”

“Roger.” I started winding in the periscope.

“While you’re doing that, we are not sure whether or not your landing bag has deployed. We feel it is possible to reenter with the retro package on. We see no difficulty this time in that type of reentry. Over.”

“Roger, understand.”

I was now at the upper limits of the atmosphere as I went to full manual control, in addition to the autopilot so I could use both sets of jets for attitude control. “This is Friendship Seven. Going to fly‑by‑wire. I’m down to about fifteen percent [fuel] on manual.”

“Roger. You’re going to use fly‑by‑wire for reentry and we recommend that you do the best you can to keep a zero angle during reentry. Over.”

I entered the last set of hurdles at an altitude of about fifty‑five miles. All the attitude indicators were good. I moved the controller to roll the capsule into a slow spin of ten degrees a second that, like a rifle bullet, would hold it on its flight path. Heat began to build up at the leading edge of a shock wave created by the capsule’s rush into the thickening air. The heat shield would ablate, or melt, as it carried heat away, at temperatures of three thousand degrees Fahrenheit, but at the point of the shock wave, four feet from my back, the heat would reach ninety‑five hundred degrees, a little less than the surface of the sun. And the ionized envelope of heat would black out communications as I passed into the atmosphere.

Al said, “We recommend that you…” That was the last I heard.

There was a thump as the retro pack straps gave way. I thought the pack had jettisoned. A piece of steel strap fell against the window, clung for a moment, and burned away.

“This, Friendship Seven. I think the pack just let go.”

An orange glow built up and grew brighter. I anticipated the heat at my back. I felt it the same way you feel it when somebody comes up behind you and starts to tap you on the shoulder; but then doesn’t. Flaming pieces of something started streaming past the window. I feared it was the heat shield.

Every nerve fiber was attuned to heat along my spine; I kept wondering, “Is that it? Do I feel it?” But just sitting there wouldn’t do any good. I kept moving the hand controller to damp out the capsule’s oscillations. The rapid slowing brought a buildup of G forces. I strained against almost eight Gs to keep moving the controller. Through the window I saw the glow intensify to a bright orange. Overhead, the sky was black. The fiery glow wrapped around the capsule, with a circle the color, of a lemon drop in the center of its wake.

“This Friendship Seven. A real fireball outside.”

I knew I was in the communications blackout zone. Nobody could hear me, and I couldn’t hear anything the Cape was saying. I actually welcomed the silence for a change. Nobody was chipping at me. There was nothing they could do from the ground anyway. Every half minute or so, I checked to see if I was through it.

“Hello, Cape. Friendship Seven. Over.”

“Hello, Cape. Friendship Seven. Do you receive? Over.”

I was working hard to damp out the control motions, with one eye outside all the time. The orange glow started to fade, and I knew I was through the worst of the heat. Al’s voice came back into my headset. “How do you read? Over”

“Loud and clear. How me?”

“Roger; reading you loud and clear. How are you doing?”

“Oh, pretty good.”

The Gs fell off as my rate of descent slowed. I heard Al again. “Seven, this is Cape. What’s your general condition? Are you feeling pretty well?”

“My condition is good, but that was a real fireball, boy. I had great chunks of that retro pack breaking off all the way through.”

At twelve miles of altitude I had slowed to near subsonic speed. Now, as I passed from fifty‑five thousand to forty‑five thousand feet, the capsule was rocking and oscillating wildly and the hand controller had no effect. I was out of fuel. Above me through the window I saw the twisting corkscrew contrail of my path. I was ready to trigger the drogue parachute to stabilize the capsule, but it came out on its own at twenty‑eight thousand feet. I opened snorkels to bring air into the cabin. The huge main chute blossomed above me at ten thousand feet. It was a beautiful sight. I descended at forty feet a second toward the Atlantic.

I flipped the landing bag deploy switch. The red light glowed green, just the way it was supposed to.

The capsule hit the water with a good solid thump, plunged down, submerging the window and periscope, and bobbed back up. I heard gurgling but found no trace of leaks. I shed my harness, unstowed the survival kit, and got ready to make an emergency exit just in case.

But I had landed within six miles of the USS Noa , and the destroyer was alongside in a matter of minutes. Even so, I got hotter waiting in the capsule for the recovery ship than I had coming through reentry. I felt the bump of the ship’s hull, then the capsule being lifted, swung, and lowered onto the deck. I radioed the ship’s bridge to clear the area around the side hatch, and when I got the all‑clear, I hit the firing pin and blasted the hatch open. Hands reached to help me out. “It was hot in there,” I said as I stepped out onto the deck. Somebody handed me a glass of iced tea.

It was the afternoon of the same day. My flight had lasted just four hours and fifty‑six minutes. But I had seen three sunsets and three dawns, flying from one day into the next and back again. Nothing felt the same.

I looked back at Friendship 7. The heat of reentry had discolored the capsule and scorched the stenciled flag and the lettering of United States and Friendship 7 on its sides. A dim film of some kind covered the window. Friendship 7 had passed a test as severe as any combat, and I felt an affection for the cramped and tiny spacecraft, as any pilot would for a warplane that had brought him safely through enemy fire.

The Noa like all ships in the recovery zone, had a kit that included a change of clothes and toiletries. I was taken to the captain’s quarters, where two flight surgeons helped me struggle out of the pressure suit and its underlining, and remove the biosensors and urine collection device. I didn’t know until I got the suit off that the hatch’s firing ring had kicked back and barked my knuckles, my only injury from the trip. My urine bag was full. A NASA photographer was taking pictures. After a shower, I stepped on a scale; I had lost five pounds since liftoff. President Kennedy called via radio‑telephone with congratulations. He had already made a statement to the nation, in which he created a new analogy for the exploration of space: “This is the new ocean, and I believe the United States must sail on it and be in a position second to none.”

I called Annie at home in Arlington. She knew I was safe. She had had three televisions set up in the living room, and was watching with Dave and Lyn and the neighbours with the curtains drawn against the clamor of news crews outside on the lawn. Even so, she sobbed with relief. I didn’t know then that Scott had called to prepare her in case the heat shield was loose. He had told her I might not make it back. “I waited for you to come back on the radio,” she said. “I know it was only five minutes. But it seemed like five years.”

Hearing my voice speaking directly to her brought first tears, then audible happiness.

After putting on a jumpsuit and high‑top sneakers, I found a quiet spot on deck and started answering into a tape recorder the questions on the two‑page shipboard debriefing form. The first question was, what would you like to say first?

The sun was getting low, and I said, “What can you say about a day in which you get to see four sunsets?”

Before much more time had passed, I got on the ship’s loudspeaker and thanked the Noa’s crew. They had named me sailor of the month, and I endorsed the fifteen‑dollar check to the ship’s welfare fund. A helicopter hoisted me from the deck of the Noa in a sling and shuttled me to an aircraft carrier, the USS Randolph , where I met a larger reunion committee. Doctors there took an EKG and a chest X ray, and I had a steak dinner. Then from the Randolph I flew copilot on a carrier transport that took me to Grand Turk Island for a more extensive medical exam and two days of debriefings.

At the debriefing sessions, I had the highest praise for the whole operation, the training, the way the team had come back from all the cancellations, and the mission itself – with one exception. They hadn’t told me directly their fears about the heat shield, and I was really unhappy about that. A lot of people, doctors in particular, had the idea that you’d panic in such a situation. The truth was, they had no idea what would happen. None of us were panic‑prone on the ground or in an airplane or in any of the things they put us through in training, including underwater egress from the capsule. But they thought we might panic once we were up in space and assumed it was better if we didn’t know the worst possibilities.

I thought the astronaut ought to have all the information the people on the ground had as soon as they had it so he could deal with a problem if communication was lost. I was adamant about it. I said, “Don’t ever leave a guy up there again without giving him all the information you have available. Otherwise, what’s the point of having a manned program?”

It emerged that a battle had gone on in the control center over whether they should tell me. Deke and Chris Kraft had argued that they ought to tell me, and others had argued against it, but I didn’t learn that until many years later. I don’t know who had made the decision, but they changed the policy after that to establish that all information about the condition of the spacecraft was to be shared with the pilot.

I was describing the luminous particles I saw at each sunrise when George Ruff, the psychiatrist, broke up everyone in the debriefing by asking, “What did they say, John?” (The particles proved to be a short‑lived phenomenon. The Soviets called them the Glenn effect; NASA learned from later flights that they were droplets of frozen water vapor from the capsule’s heat exchanger system, but their firefly‑like glow remains a mystery.)

George also had a catch‑all question tagged on at the end of the standard form we filled out at the end of each day’s training. It was, Was there any unusual activity during this period?

“No,” I wrote, “just the normal day in space.”

Grand Turk was an interlude, in which morning medical checks and debriefing sessions were followed by afternoons of play. Scott, as my backup, stuck with me as I had Al and Gus after their flights. We went scuba diving and spearfishing, and Scott rescued a diver who had blacked out eighty feet down, giving him some of his own air as he brought him to the surface. There were no crowds, since the debriefing site was closed.

Annie had tried to give me some idea of the overwhelming public reaction to the flight. Shorty Powers had said there was a mood afoot for public celebration. But I was only faintly aware of the groundswell that was building.

Project Mercury returned to space on May 24, with Scott’s three‑orbit flight in Aurora 7. Deke had been scheduled to make the flight, but the doctors had grounded him after detecting a slight heart murmur.

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-13; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1302;