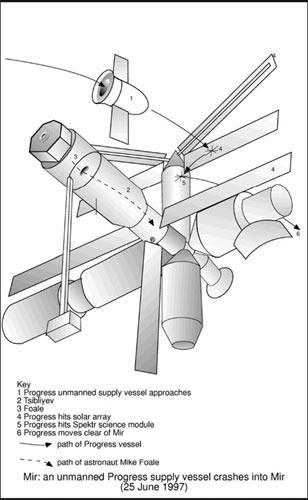

An unmanned Progress supply vessel crashes into Mir

On 25 June a Progress was due. They were to repeat the docking test, taking over control of the supply vessel from 7km out, but this time they would be out of communication with TsUP until the Progress was 50m from Mir. If a docking was aborted while the Progress was over 400m away it would miss Mir. Within that distance no one knew what would happen. TsUP told Tsibliyev that the Progress was approaching on schedule. This time the camera on the Progress worked but the automatic docking system (BPS) did not. The BPS signalled that the Progress was ready to fire its thrusters but 17 minutes from docking there was no receipt signal. Tsibliyev switched to manual docking using the TORU and sent Foale to Kvant to check the distance using a laser range finder. The Kurs radar which could provide that information had been automatically switched off. There was a possibility that this had caused failure of the camera on board the Progress. At this point they couldn’t see the Progress either on screen or through a window, although they estimated it was only 2.5km out.

At 12:06:51, with Lazutkin and Foale floating silently behind him, looking out their windows, Tsibliyev released the braking lever. According to the instructional memo, the Progress should have been just a kilometre or slightly less above them, moving down toward the docking port. Once the ship arrived at a point about 400 metres away from the station, Tsibliyev would slow its speed to a crawl and begin inching it forward to the 50‑metre point, where it would be readied for a soft docking at the Kvant docking port.

When the TsUP’s plan had 90 seconds to go the Progress should have been approaching the 400‑metre mark, but neither Lazutkin, peering out of window No.9, nor Foale could see anything. Both men knew the ship had to be out there somewhere, just beyond their view; on the screen, the station now filled four entire squares on the checkerboard overlay. An eerie feeling washed over Lazutkin. Looking at Tsibliyev’s screen, he felt as if he was being watched. But no matter what they did, they could not find the onrushing watcher.

Tsibliyev nudged the braking lever one final time.

“It’s moving down,” he said.

Suddenly Lazutkin spotted the oncoming Progress, emerging from behind a solar array that until that moment had blocked his view. The ship appeared huge – bigger than he could have imagined.

It was heading right for them.

“My God, here it is already!” Lazutkin yelped.

Tsibliyev couldn’t believe it.“What?”

“It’s already close!”

“Where is it?”

Now everything began to happen fast. As Lazutkin looked out through the window, the brightly sunlit Progress appeared to be heading straight for a collision with base block, its twin solar arrays making it appear like some shiny white bird of prey swooping down on them.

“The distance is one hundred fifty metres!” he shouted.

Tsibliyev thought Lazutkin must be mistaken. His left pinkie remained clamped on the braking lever. The Progress should have been moving at a crawl.

“It’s moving closer!” Lazutkin said. He looked outside again and saw the big ship coming on inexorably.“ It shouldn’t be coming in so fast!”

“It’s close, Sasha, I know; I already put it down!”

Tsibliyev was holding the controls tightly, his left pinkie clamped on the braking lever. The ship should have been slowing. It didn’t seem to be responding.

To his horror, Lazutkin saw the Progress pass over the Kvant docking port and begin moving down the length of base block.

Tsibliyev saw it on the screen.

“We are moving past!” he shouted.

Lazutkin remained glued to the window.

“It’s moving past! Sasha, it’s moving past!”

Lazutkin watched the Progress come on then turned to Foale.

“Get into the ship, fast!” he told Foale, directing him to the Soyuz.

“Come on, fast!”

Foale, who had still not seen the Progress, acted quickly, pushing off the wall, shooting across the dinner table, and hurled over Tsibliyev’s head toward the Soyuz, which rested at its customary docking port on the far side of the node. Then, just as Foale passed over the commander, something happened that may or may not have had a profound effect on all their lives. One of Foale’s feet whacked Tsibliyev’s left arm. Later, everyone on board disagreed on the effect this accidental bump may have had on the path of the onrushing Progress.

As Foale passed, Tsibliyev sat frozen at the controls, his face a mask of concentration. He was convinced he could keep the Progress out away from the station, that if he held tightly enough to its current course it would still miss them. Not until the last possible second, when the hull of the station ominously filled his entire screen, did the commander realize there was no avoiding a collision.

“Oh, hell!” Tsibliyev yelled.

As the black shadow of the Progress soared by his window, Lazutkin closed one eye and turned his head.

The impact sent a deep shudder through the station. To Lazutkin, still glued to the base block window, it felt like a sharp, sudden tremor, a small earthquake. Foale, swimming through the node toward the open mouth of the Soyuz, felt the violent vibration when his hand brushed the side of the darkened chamber.

“Oh!” Tsibliyev shouted, as if in pain. He stared at his screen, barely comprehending what had happened. He said aloud, “Can you imagine?”

The master alarm sounded, eliminating all but shouted conversation.

“We have decompression!” Tsibliyev yelled. “It looks like it hit the solar panel! Hell! Sasha, that’s it!”

Confusion broke out as Lazutkin turned and began to swim toward the node, intent on readying the Soyuz for immediate evacuation.

“Wait, come back, Sasha!” Tsibliyev barked.

It was the first decompression aboard an orbiting spacecraft in the history of manned space travel. As Lazutkin hovered beside him, waiting for an order, Tsibliyev remained at his post, staring at the screen, like the captain of a stricken ship.

“How can this be?” he asked.“How can this be?”

After that his words were drowned out in the manic din of the master alarm.

Floating alone in the node, Foale paused. After a moment he realized he was still alive. His ears popped, just a bit, telling him that whatever hole had been punctured in the hull, it was probably a small one. The station’s wounds, whatever they were, were not immediately fatal. They should have enough time to evacuate.

He turned and faced the entrance to the Soyuz, where a tangle of cables, a mass of gray‑white spaghetti, spilled out of the escape craft’s open mouth. Executing a deft little flip, he turned backward and entered the Soyuz feet first, extending his legs behind him, his head and shoulders protruding from the capsule.

As he turned to look back toward base block, Foale fully expected Lazutkin and Tsibliyev to come charging into the node after him to begin the evacuation. They didn’t. Foale waited five, ten, then twenty seconds. There was no sign of the Russians. They remained somewhere back in base block, out of his sight.

After roughly a minute of waiting, Foale began to worry. He was certain the Progress struck the station either in base block or in Kvant. These were considered “non‑isolatable” areas – that is, a hull breach in either area could not be sealed off. In emergency drills simulating a meteorite strike against the hull of either module, the crew was given no option but to abandon ship. Foale couldn’t understand why Lazutkin and Tsibliyev weren’t evacuating.

Tsibliyev swivelled out of his seat and crouched by the floor window behind him. There, barely 30 feet away, so close he felt he could reach out and touch it, he saw the Progress sagging against the base of one of Spektr’s solar arrays. It looked as if the long needle on the leading edge of the cargo ship’s hull had pierced a jagged hole in the array’s wing‑like expanse. He couldn’t be certain, but the Progress appeared lodged against the hull. Lazutkin crouched by the window and looked down. He saw it too.

The commander turned, thinking he would fire one of Progress’s forward thrusters to, as he later put it, “kick it” off the station. But just as he began to leave the window, he saw the cargo ship shift and move forward once again, striking and denting a boxy gray radiator on the side of Spektr’s hull. Then it kept moving forward and, after a long moment, floated free again.

Tsibliyev held his breath, hoping that the Progress would now fly free of the station without hitting any more of its outer structures.

“Where are they?”

Foale couldn’t understand what Tsibliyev and Lazutkin were doing. Emergency procedures mandated that they immediately evacuate the station, but the two Russians were nowhere to be seen. It occurred to Foale that his two crewmates were doing something to try and save the station, when they should be evacuating it. He knew that this kind of going‑down‑with‑the‑ship mentality wouldn’t have been unusual among the pride‑soaked cosmonaut corps; it was precisely the reckless kind of behaviour Linenger had been warning everyone about. Foale crawled out of the Soyuz and began to fly back toward base block, intent on finding out what was going on.

But the moment Foale emerged from the Soyuz, Lazutkin hurtled out of base block into the node. In a flash he was at the little ship’s entrance. Foale, realizing that Lazutkin was now prepared to begin the evacuation, was unsure of his role.

“Sasha, what can I do?” he asked.

Lazutkin ignored or didn’t hear the question; the alarm was so loud it was difficult to hear anything. Moving with the fury of a man in hand‑to‑hand combat, Lazutkin grabbed the giant, worm‑like ventilation tube and tore it in half. Wordlessly he seized cable after cable, furiously rending each one at its connection point. Foale watched in silence.

It took Lazutkin barely a minute to disconnect all the cables. Finally only one remained. It was the PVC tube, which channelled condensate water from the Soyuz into the station’s main water tanks. Lazutkin could not separate it with his hands. He needed a tool.

A wrench. They needed a wrench. Lazutkin looked frantically for one all around the node, which was lined with spare hatches and tools and equipment. He and Foale spent nearly a minute in search of a wrench before Lazutkin found one, floating by a blue thread. He handed it to Foale and showed him how to unfasten the PVC tube. Foale retreated into the Soyuz, applied the wrench, and began turning as fast as he could.

When he was certain Foale knew how to unfasten the PVC tube, Lazutkin turned toward the entrance to the Spektr module. Foale, while saying nothing aloud, remained convinced the leak was in base block or Kvant. Lazutkin didn’t have to guess. He had seen the Progress lodged against the Spektr module’s solar array. He assumed that whatever breach the hull had suffered, it almost certainly occurred in Spektr. Lazutkin pushed off from the Soyuz entrance, arced across the node, and shimmied into Spektr.

Diving head first into the module, he immediately heard an angry hissing noise from somewhere below and to his left. It was, he knew, the sound of air escaping into space. His heart sank. At this moment, Sasha Lazutkin was certain they were all about to die.

On Mir the hatchways between the modules were 3 feet in diameter. There were cables running through them so that they couldn’t be closed without cutting or removing the cables.

Lazutkin realized immediately that in order to save the station, he had to somehow seal off Spektr. Like all the other hatchways, it was lined with wrapped packets of thin white and gray cables, 18 cables in all, plus a giant worm‑like ventilation tube.

A knife, Lazutkin thought: I’ve got to find a knife to cut the cables. While Foale remained inside the Soyuz, finishing off the PVC tube, Lazutkin soared back through the node and dived headfirst into base block, where he saw Tsibliyev poised to begin talking to the ground. Vaulting over the commander’s head, Lazutkin shot down the length of base block, past the dinner table, and into the mouth of Kvant. He remembered a large pair of scissors he had stowed alongside one of the panels, but when he reached the panel, he was heartsick: the scissors weren’t there. Then he saw a tiny, four‑inch knife – “better to cut butter with than cables,” as Lazutkin remembered it. Normally he used the blade to peel the insulation off cables that needed to be rewired.

Lazutkin grabbed the knife and flew back down to the node. Sticking his upper body into Spektr, he grabbed a bundle of cables and instantly realized his plan wouldn’t work: the cables were too thick to be cut with his little blade. Each of the bundles was fitted into one of dozens of connectors that lined the inside of the hatch. Frantically Lazutkin began grabbing the cable bundles one after another, unscrewing their connections and tossing the loose ends aside, to float in the air.

After a moment Foale emerged from the Soyuz, where he had finally disconnected the PVC tube, just as Lazutkin finished ripping apart the first few cables. Foale was immediately surprised to see Lazutkin working at the mouth of Spektr. Still believing the leak was somewhere back in base block or Kvant, he was convinced that Lazutkin was isolating the wrong part of the station. If Foale was correct, sealing off Spektr would be a disastrous move. It would actually reduce the station’s air supply, thereby causing Mir’s remaining atmosphere to rush out of the breach even faster.

Foale remembered:

“I was still very concerned we were isolating the wrong place. I was not going to stop him physically – yet. But that was my next thought: Should I try and stop him?”

Burrough:

Instead, intimidated by the sheer fury with which Lazutkin was tearing at the cables, Foale floated by and watched. As Lazutkin rended each line, its loose end floated out into the node – “eighteen snakes floating around, like the head of Medusa,” Foale recalled. Foale began grabbing the loose lines and binding them with rubber bands he found in the node. Finally, he said something.

“Why are we closing off Spektr? It’s the wrong module to close off. If we’re gonna do a leak‑isolation thing, we have to start with Kvant 2.”

Foale was about to say more, when Lazutkin cut him off.

“Michael,” he said, “I saw it hit Spektr.”

And with that Foale at last fathomed Lazutkin’s urgency: seal Spektr, and they save the station.

It took almost three minutes for Lazutkin to tear apart fifteen of the eighteen cables. The remaining three cables didn’t have any visible connection points. They were solid and unbreakable. Lazutkin thought of the knife. He retrieved it from his pocket and slashed a thin data cable for one of the NASA experiments. The next moment he slashed a leftover French data cable from one of the Euro‑Mir missions. One cable remained. One cable whose removal would allow them to seal the hatch and save the station.

But Lazutkin received a rude shock when he began sawing into the last and thickest of the three cables. Sparks flew up into his face. It was a power cable.

Foale saw a frightened look cross the Russian’s face.

“Sasha, go ahead!” Foale urged. “Cut it!” A beat. “Cut it!”

But he wouldn’t. He wouldn’t cut it.

At the moment the Progress struck the station, Mir was just coming into communications range of TsUP. Burrough:

It was at this point that Tsibliyev, still floating anxiously at the command center in base block, heard the TsUP hailing him. Nikolai Nikiforov, the shift flight director, was at the command console in the TsUP. Vladimir Solovyov stood out of sight in a separate control room used for Progress operations. There was static, and for a moment Tsibliyev’s words could not be heard.

“Siriuses!” Nikiforov shouted. “Siriuses!”

Suddenly Tsibliyev’s voice broke through the static. “Yes, yes, we copy! There was no braking. There was no braking. It just stalled. I didn’t manage to turn the ship away. Everything was going on fine, but then, God knows why, it started to accelerate and run into module O, damaged the solar panel. It started to [accelerate], then the station got depressurized. Right now the pressure inside the station is at 700.”

Sirius was Mir’s codename. Module O was Spektr.

Soloyov, immediately realizing what had happened, got on comm. Burrough:

“Guys, where are you now?”

“We are getting into the [Soyuz]…”

Chaos broke out for several moments on the floor of the TsUP as Solovyov and the other controllers tried to determine exactly what was happening aboard the station. The comm broke up for a moment.

“Copy, damn it!” Solovyov barked.

“Oh, hell,” Tsibliyev blurted out. “We don’t know where the leak is.”

“Can you close any hatch?” interjected Nikiforov.

“We can’t close anything,” Tsibliyev said hurriedly. “Here everything is so screwed up that we can’t close anything.”

As Tsibliyev’s words crackled over the auditorium loudspeakers, Keith Zimmerman couldn’t understand anything the commander was saying: he spoke very little Russian. Then, suddenly, his interpreter said, “They hit something.”

Zimmerman wrinkled his brow. “What do you mean?” he said. From the interpreter’s even tone of voice, he guessed that maybe one of the cosmonauts had hit his thumb with a hammer.

“The Progress,” Aleksandr said quietly. “It hit the station. The pressure’s going down.”

Zimmerman went numb. This was not something a 29‑year‑old MOD assistant was accustomed to hearing.

“Wait, Vasya, what are you doing now?” Nikiforov asked.

“We are getting ready to leave. The pressure is already at 690. It continues to drop.”

“Can you switch on any blowers?”

“I think we can.”

“Open all existing oxygen tanks.”

“Sasha,” Tsibliyev hollered to Lazutkin, “have you closed the hatch?”

Lazutkin’s reply was drowned out as the station’s master alarm continued braying.

“Vasya,” said Solovyov, “what are you doing now?”

“DSD has turned on. We managed to close the hatch to module O.” This was wishful thinking: as Tsibliyev spoke, Lazutkin still hadn’t cleared the last cable from the hatch. DSD was a depressurization sensor.

“Module O. Has [the Progress] run into module O?”

“Yes, it hit module O.”

“Is the hatch closed right now?”

“Sasha is closing it right now.”

“What’s happening with the pressure?”

“DSD turned on when pressure dropped down to 690.”

Solovyov interjected. “Can you pass through [the node] right now? We should have extra [oxygen] tanks somewhere in TSO.”

“I know that,” said Tsibliyev. TSO refers to the air lock at the end of the Kvant 2 module.

Solovyov’s call for Tsibliyev to retrieve one of the station’s pumpkin‑size oxygen cylinders was a standard response to depressurization scenarios in both Russian and American simulations; until this moment it had never been tried in an actual crisis. Releasing oxygen into the Mir’s atmosphere, Zimmerman realized, meant Solovyov had decided to begin “feeding the leak” – that is, replacing air that had already begun to whistle through whatever hole the Progress had poked in the hull of the Spektr module. Feeding the leak wouldn’t save the station, but it should give the crew precious extra minutes. How many depended on how fast the station was losing air.

“So open them up,” Solovyov ordered.

“I [will start] doing that right now. I am taking off the ears” – the headphones – “and am taking off to do that.”

“But someone has to stay here to maintain the connection!” Solovyov pleaded.

“Then I can’t make it.”

Tsibliyev did it anyway. Ripping off his headphones, he left his post, turned, and swam out over the command console and into the node.

“Guys?” Solovyov asked. “Someone pick up!”

There was no answer.

“Sasha?”

No answer.

“They have left… Guys? Someone respond.”

Lazutkin wouldn’t cut the power cable. Again he and Foale plunged down into the darkened morass of loose cords and equipment and lids and seals that lined the node walls. Somewhere in the chamber’s dim recesses, Lazutkin believed there must be a plug for the power cable. Foale ripped aside cable bundles and ran his hands over the walls. Lazutkin craned his head, looking, looking.

There. Lazutkin pulled at the power cable and followed it to a plug inside Spektr. With one furious yank, he ripped it from the wall.

Immediately Foale and Lazutkin turned to confront Spektr’s inner hatch. Lazutkin reached into the module and pulled on the hatch to close it.

It wouldn’t budge.

Both men instantly saw the problem. With the pressure dropping inside Spektr, all the air inside the station was rushing past them, seeking to escape through the unseen breach into open space. It was as if they were trying to close an open door while an invisible river surged through it. Lazutkin realized he could slip into Spektr and push from the inside, but then he would be trapped within the sealed module. He would die quickly, a hero of the motherland, but Sasha Lazutkin wasn’t ready to die yet.

Again he and Foale tugged at the hatch, straining to pull it closed.

It wouldn’t budge. Nothing they did would make it move a single inch.

They couldn’t close the hatch because of the air rushing through it. Tsibliyev dashed into Kvant 2 to get an oxygen cylinder. He turned it on and the pressure began to go up.

The hatch wouldn’t shut.

Its outer surface was smooth, with no easy handholds. Neither Foale nor Lazutkin could risk slipping his hands around the hatch’s outer edge, for fear of losing a finger.

“The lid! Let’s get a lid!” Lazutkin urged.

Foale realized that with the inside hatch unable to close, they would have to find a hatch cover to push onto the module’s open mouth from the outside.

Each of the four modules attached to the node originally came with a circular lid, vaguely resembling a garbage can lid, which sealed the hatch from the outside. All four of the lids were now strapped to spots on the node walls. They came in two sizes, heavy and light. Lazutkin reached for a heavy lid, but it was tied down by a half‑dozen cloth strips, each of which, he realized, he would have to slash to free the hatch cover underneath. He simply didn’t have enough time to cut all the strips.

Instead Lazutkin reached for one of the lighter covers. It was secured to the node wall by a pair of cloth straps, both of which the slim Russian quickly severed with the knife.

Together both men lifted the lid and set it over the open hatch. The lid was originally held in place by a series of hooks spaced evenly around the hatch’s outer edges, and Lazutkin thought they would have to work this mechanism to seal the hatch. But the moment the two men affixed the cover to the open hatch, the pressure differential that foiled their earlier efforts now worked in their favor. The lid was sucked tightly into place.

Lazutkin wasn’t satisfied. He told Foale to support the hatch cover while he found the tool he needed to work the closing mechanism.

“Vasya,” Solovyov said, “what hatch are they closing in module O? The one that needs to be pushed out or pulled in?”

“Which one are you closing?” Tsibliyev yelled over at Lazutkin.

Lazutkin said something inaudible.

“The one that will be pushed toward the module,” said Tsibliyev.

“You mean the one that is part of the main module.”

“It’s like a lid that will be pressed on.”

“Understood. So you are putting on the lid? Do you have some knife? Can you unplug the cables?”

“Yes, we have closed it and with that the light indicating depressurization has turned off.”

At the NASA console Keith Zimmerman breathed a tiny sign of relief. This was the first good news he had heard. He scanned the telemetry on his screen, paying close attention to the pressure levels. If the damage was limited to Spektr, and Spektr’s hatch had been firmly sealed, the pressure should hold steady.

At 12:21 the Progress was over 300m away orbiting the station. The pressure was slowly coming up. Mission Control’s systems indicated that Mir was drifting. They asked: “What’s happening with SUD right now? Is it in the ‘indication’ mode?”

SUD referred to the station’s motion‑control system; if it had entered indication mode, Mir was in free drift and thus unable to keep the solar arrays toward the sun.

“Yes.”

“Then we’ll leave it.”

With the station in free drift, its remaining solar arrays were unable to track the sun and thus generate power. With no new power coming into the system, the existing onboard systems would slowly begin to drain what power was left in the station’s onboard batteries. It would take several hours for the batteries to drain altogether, longer if the crew shut down most of the station’s major systems. Solovyov, his eye already on the approaching end of the comm pass, began instructing Tsibliyev which systems to shut down, and in what order, in the event power levels began dropping while the station was out of contact with the ground.

“We are switching [off] all that is not vitally important,” Tsibliyev said.

“If you have real trouble with SEP” – SEP referred to power levels remaining in the batteries – “the priorities will be the following: first switch off the Elektron, and only in the last moment [switch off] Vozdukh.” The Vozdukh carbon dioxide scrubber was the last thing Solovyov wanted turned off, since the station was already running low on the replacement LiOH canisters.

“Elektron is switched off right now,” said Tsibliyev.

“You should be fine with SEP. Just try to save it, but I don’t think you will be anywhere near to switching off Vozdukh.”

“We’ll be watching the pressure gauge.”

“What’s the temperature right now?”

“It’s quite chilly.”

“You should give [the pressure] time to stabilize.”

“I didn’t get you.”

“The pressure has to stabilize.”

“Okay.”

“What’s the pressure right now?”

“689 and holding.”

The enormity of what had happened overcame Tsibliyev for a moment. “It’s so frustrating, Vladimir Aleexevich,” he blurted out. “It’s a nightmare.”

“That’s all right, Vasily,” replies Solovyov, trying to keep his commander focused. Albertas Versekis, a docking specialist, joined Solovyov at his console. “Now tell Albert chronologically what was happening with the Progress.”

“Everything was going as planned. We were thinking that we should give it some more space for acceleration. We ended up not doing it.”

“All right.”

“I started to put down the lateral velocity. It started to sink down. And then there was permanent braking–”

“Were you braking?”

“Yes, and I was trying to bring it down. I was holding it tightly with my hand to make sure that it passed away from the solar panel. It indeed passed on the side, but then it slightly bent to the left and punched the top solar panel of module O with the needle. Then it touched the attachable cold radiator with its top solar panel on the right side.”

“Did it damage it?”

“Yes, a bit. However it bounced back immediately. It seems the speed was not that great at that moment, and we probably did not have enough energy to brake [the Progress].”

“Got you.”

And then the pass was over. It was 12:42.

The crew were reunited. Foale and Lazutkin smiled but Tsibliyev was silent and dazed. While they waited for the next communications pass, they speculated as to whether the contact between Foale and Tsibliyev had caused the collision. Lazutkin:

“Before Michael hit Vasily with his foot, the Progress was flying straight toward Spektr, its back end pointing forward. [Vasily] took his hand off the controls, and the ship changed its position. As soon as Michael hit Vasily’s hand, [the ship] moved, and it hit Spektr with its side. If the ship had continued flying the way it was flying, it might have been much worse. It would have hit with the sharp edge of the rear, rather than the blunt edge of the side.”

Subsequent examination of the videotape did not show any change in the path of the Progress. Tsibliyev concluded:

“The fact is little things contributed to what happened and we had a collision, that was one of the little things.”

They needed to get the solar arrays pointed back toward the sun. The station was in a slow roll and they needed to stop this. Because the solar arrays were misaligned, the station was running off stored power in the batteries. Four minutes before the next communications pass, the lights went out in the base block, then the rest of the lights went out and the gyrodynes powered down. Their thrusters couldn’t fire without power.

When Foale suggested using the thrusters on Soyuz to stop the spin, Mission Control gave permission to try. It was difficult to calculate the thruster firings. Tsibliyev:

“When we understood all this, and Michael had made his drawings, it turned out we had to make these very short impulse [firings]. We tried to explain it to the TsUP, but the [comm] passes were so short we couldn’t. So the TsUP said, ‘Okay, guys, you try it, let’s see what happens, because we have to do something.’”

At the end of the communications pass, they were on their own.

“We can do this, Vasily,” Foale urged Tsibliyev. The commander looked skeptical.

They returned to the Soyuz. “Okay, three seconds,” said Foale. “Try it three seconds.”

Tsibliyev pressed the thruster lever three times, quickly.

It didn’t work. Foale, looking out the windows, saw that the solar arrays remained in darkness. Foale asked:

“Vasily, how long did you hold the thruster?”

“I didn’t hold it. I just hit it.” Pop. Pop. Pop.

Foale realized Tsibliyev was being conservative in an effort to save propellant. He said:

“That won’t work, I don’t think. If you just hit it, that’s not pressure enough. We need more than that. You have to actually hold it down for three seconds.”

There were more calculations and another drawing or two before Tsibliyev finally sat and followed Foale’s directions. He nudged the thruster lever for one… two… three seconds – and released.

Foale and Lazutkin studied the rotation and the solar arrays. After a moment they began to smile.

“I think it worked,” Foale said.

The station’s new orientation left Kvant 2 without power. The toilet was in Kvant 2 so they had to use a series of condoms and bags left over from an earlier experiment.

At this point the NASA ground team began to think this was the end of Phase One of the International Space Station project. But the Russians didn’t give up – they had 20 years experience of on‑the‑spot repairs.

The recovery plan involved charging all the available batteries from the functioning solar panels. The charged batteries would be used to power the base block’s guidance and control systems and then the other modules, the whole process taking two days. TsUP wanted the cosmonauts to put on spacesuits, enter Spektr and jury‑rig a power supply there, then they could find and patch the hole which they calculated would be 3cm wide.

During the night of 26–27 June Mir lost all power due to a malfunction of the surge protectors which prevented the batteries from charging. TsUP wanted them to test the gyrodynes which drained the batteries and caused the central computer to crash. They lost all power and the crew had to begin the recovery process all over again.

By 28 June the batteries had recharged sufficiently to return powertomostofbaseblock. Therestofthe stationwould staydark until the four big solar arrays on Spektr could be reconnected. Foale improvised a movie theatre using a computer monitor and a video player, and they watched the film Apollo 13 together. Tsibliyev:

“We felt that, especially from a psychological point of view, their situation was much worse than ours – we at least had a spaceship which could get us home. With Apollo 13 they had to fly all the way around the moon in order to get back to the earth.”

Later, by email, they received a quote from Jim Lovell himself comparing the two flights:

“I understand how these guys feel, because I’ve been there as well. I know their courage and bravery.”

By 30 June NASA was considering bringing Foale back because he couldn’t do any scientific work while Spektr was sealed off.

TsUP needed to know which cables ran through the hatch to Spektr but the Russian record keeping was not up to NASA standards.

They planned an Intra Vehicular Activity (IVA) by Tsibliyev and Lazutkin while Foale remained in the Soyuz. Once inside Spektr they would reconnect the cables linking the modules which should restore the power supply. On the ground they were working out the details, especially how to modify the bulky suits to get through the narrow hatchways. At 2 am on 1 July Tsibliyev heard a sound like a muffled explosion coming from Spektr. He saw a cloud of flakes hanging around it which glistened in the sunlight. By 2 July they had gone.

Without a working ventilation system condensation was forming in the darkened modules, so Foale and Lazutkin rigged hoses to blow air into the affected modules.

On 5 July a Progress was launched, the gyrodynes were powered up to put the station in the correct position for docking and on 7 July the Progress docked safely.

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-13; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1500;