Stuart England: Civil War and Commonwealth

The economy of England, if not the largest, was probably the most advanced and complex in Europe. Still strongly based upon the cloth trade, still with a predominantly agricultural base, it showed aspects of developing industrialisation in shipyards, cannon-foundries, brickworks and ironworks. The range of trades was great. The developing skills in medicine and surgery required new and specialist instruments. New imports were coming in from west and east, including tobacco (against the use of which the new king wrote a book) and chocolate. To control and protect trading in far-off places, new businesses had been created, the Muscovy Company and the Levant Company, respectively granted monopolies on trade with Russia and the eastern Mediterranean. The regulation of this diverse activity had become the joint concern of the Council and of parliament, with some men being members of both bodies, as Sir Francis Walsingham had been. The prime function of parliament remained 'supply', the granting and securing of the royal finances.

James's policy of peaceful relations with Spain, though opposed by diehards, was a sensible one and brought dividends in trade. Salisbury's death in 1612 removed his most efficient and respected counsellor; from then on James was excessively influenced by his own court favourites. Between 1614 and 1621 he did not summon parliament at all.

TROUBLE FROM ABROAD

Despite a continuing alliance with England, Dutch merchant venturers established colonies and trading stations and organised themselves to keep English traders out. Dutch fishermen considered the North Sea their own and fought off English vessels. Having made peace with Spain, and aware that France had no fleet, the English government allowed the navy to run down, and while its merchant fleet grew, England was no longer capable of enforcing control even of its own coastline. Despite these difficulties, English colonies were successfully established in Virginia (where Jamestown became the first permanent English settlement in 1607), Bermuda and Barbados. From 1620, the private enterprise of non-conforming Puritans established the New England colonies. Acceptance of the Bohemian crown by a German prince, the Elector Palatine, who was married to James's daughter Elizabeth, widened the war until, from the extreme ends of Europe, Spanish and Swedish armies fought across German principalities and Austrian duchies, assisted by hosts of mercenaries from England, Scotland and Ireland. England played a peripheral part in this great struggle.

CHARLES I: RELIGIOUS DIVISIONS AND CONFLICT

WITH PARLIAMENT

Buckingham when James I died in February 1625, King Charles I maintained the favourite as chief minister. There were many reasons for Buckingham to have opponents and enemies. He was a social upstart, he was a corrupt counsellor who sold official posts and peerages, he encouraged the king's hostility to parliament, and he was an incompetent politician and an inept general. Almost his only useful contribution was, as Lord High Admiral, to develop the use of frigates for the royal navy.

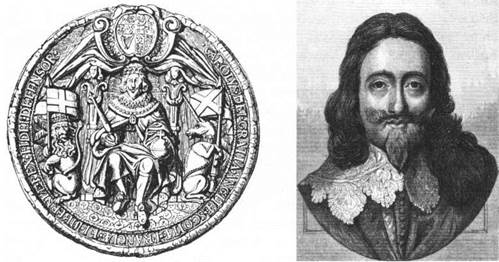

The great Seal of Charles I Charles I

Buckingham's continued role played a large part in parliament's reserved attitude to Charles I at the start of his kingship: instead of granting the king ‘tunnage and poundage’ (the proceeds of import and export duties) for life, or an extended period, it gave him only one year. War had been declared on Spain in 1624, and Charles extended hostilities to France in 1626. Such campaigns as there were, including an attempt to replicate Drake's old success at Cadiz, and an expedition led by Buckingham against the lie de Re in France, were failures. Buckingham, defended by the king against parliamentary impeachment, was assassinated by a disgruntled officer in 1628.

SCOTLAND REVOLTS

The unravelling of Charles I's royal autocracy began in an unexpected place. Charles mustered an army to restore the Scots to discipline. The Scots mustered an army that was altogether more formidable than the ill-trained royal levies, and a peace was patched up, though it was plainly not going to last. The Scottish army, encamped in the north and subsidised at £850 a day, was the guarantor that the parliament would not be dissolved by royal order. Names that would soon ring out on battlefields participated in its work, including the quiet but influential member for Huntingdon, Oliver Cromwell.

PARLIAMENT GAINS THE UPPER HAND

In October 1641, news of a rebellion in Ireland, under Catholic leadership, brought anti-Catholic feeling to new heights, whipped on by hysterical speeches and propaganda. This artificial climate of suspicion and tension endured into 1642, while attitudes hardened both on the religious and political issues. Perhaps in anticipation of attempts to impeach the queen, Charles's attorney-general impeached five members of the Commons and one peer, and on 4 January, with a large force of soldiers, the king came himself to the House of Commons to arrest them. Forewarned, they had taken refuge in London, which became almost on the instant an openly insurgent city The king left for the north, where he would still find loyal support.

In April he was refused entry to the city of Hull, where an arsenal of weapons was stored. Opposing authorities were now publicly asserted. Parliament set about raising a militia. Bу July, opposing bands of royalist and parliamentary supporters were already fighting. On 20 August, at Nottingham, the king raised his standard and called on all who supported him to join the ranks. With both sides protesting that they were defending England's ancient rights, laws and customs, the Civil Wars began.

THE CIVIL WARS

Beginning as a constitutional war, exacerbated by religious dispute, its ending was dominated by struggles between different religious factions. At the start, the royalists' great asset was the king himself. He was still king of the whole nation and could command a strong traditional loyalty across the population. The royalist troops based in Oxford gained an ugly reputation for looting. Most of the nobility rallied to the king, and he had strong support in the West Country and the north. From his headquarters at Oxford, Charles still commanded a great swathe of the country. A 'self-denying ordinance' forbade members of parliament also to be commanders in the field. By irresistible demand from the ranks of the army, one exception was made to this: the Lieutenant General of Cavalry, Oliver Cromwell. Parliament's 'new model' army, with Fairfax as general and Cromwell as his deputy, was paid, trained, disciplined, and instilled, from its leaders down, with a will to win. 'Ironsides' was Rupert's nickname for Cromwell; it soon spread to his troopers. On 14 June 1645, with Charles I leading his troops, the royal army suffered a decisive defeat at Naseby. A push to the west followed and the royalists of Cornwall surrendered in March 1646. As the parliamentary forces set about besieging Oxford, the king slipped out and in April gave himself up to the Scottish army which was encamped at Newark.

PARLIAMENT DIVIDED: THE ARMY GAINS CONTROL

This brought about an end to hostilities and a whole new set of uncertainties. Charles had surrendered his person but not his cause. For nine months the Scots held him while negotiations went on. The Scots wanted to see the Solemn League and Covenant implemented. When it was finally plain that Charles would never agree to this, they washed their hands of him. Prominent campaigners for the king were heavily fined and frequently forced to sell off their land to friends of parliament. A great mass of the middle ground population were angered by the suppression of Anglican worship, the forbidding of the Prayer Book, and the ousting of some two thousand parish clergy. The Independents were enraged by such measures as life imprisonment for Baptists, and the prohibition of laymen from preaching. These issues were brought to climax by an ordinance for disbandment of the army, apart from a few regiments retained to subdue Ireland. The war was won, and the cost of a standing army was very great; there were growing complaints about the level of taxation required. But the soldiers' pay was in arrears, and the new model army was imbued with the spirit of the Independents. The army refused to stand down, and at its head, looming larger than Fairfax, his nominal superior, was Oliver Cromwell, now the most powerful man in England.

Cromwell, backed by his able son-in-law, Henry Ireton, took possession of the king and brought the army to London. By August, Fairfax and Cromwell's regulars had smashed the royalists. The army was now in indisputable control of the country. When the Long Parliament met again on 6 December 1648, Colonel Thomas Pride seized 137 members, all Presbyterians, placing 41 under arrest. Sixty Independents now formed the House of Commons, a 'Rump' even less representative of the country than the previous assembly It proceeded to take momentous decisions, passing a bill to arrange the trial of the king, and voting that 'to levy war against the Parliament and realm of England was treason'. A special High Court was convened to try the king. No judge would sit in it, and Fairfax would have none of it, but Cromwell, backed by the army, pressed on. Denying the legitimacy of the proceedings, Charles refused to plead. He was found guilty, sentenced to death, and beheaded in front of a great, silent crowd in Whitehall on 30 January 1649.

Oliver Cromwell

ENGLAND LOSES A KING – AND BECOMES

A COMMONWEALTH

England was proclaimed to be a 'Commonwealth', under the government of the House of Commons and a Council of State, with Cromwell as its chairman. The House of Lords was abolished.

Such events encouraged the extreme democrats among the army rank and file, 'Levellers' and 'Diggers' who demanded annual parliaments and social equality, but their disjointed attempt at a coup was forcibly put down by Cromwell, who did not share these aspirations. Ireland, still in a state of revolt, and Scotland, which had proclaimed Charles II as its king, were to be incorporated into the Commonwealth, which claimed all the dominions of the executed king. Cromwell took an army to Ireland and commenced the subjection of the country, which Ire ton completed in 1650. Cromwell meanwhile turned on the Scots, but in 1651 the Scots brought war into England, when Charles II accompanied an invading army. The hope was to arouse English support, but little was forthcoming, and Cromwell defeated them at Worcester on 3 September 1651. Charles II fled abroad. With the 'crowning mercy' of Worcester, the Civil Wars were ended, and England faced a new era.

The lowest point of English estimation of Oliver Cromwell came at the restoration of the kingdom in 1660, when his decayed corpse was exhumed, dismembered and abused. His old admirers kept their heads down. The highest point was when he was offered the crown, in 1656. But the stock of the great king-slayer has generally been high, in a deeply monarchic country. This is partly owed to his personal qualities of honesty and sincerity, but mostly to the fact that his rule was successful. The Commonwealth was born in the immediate aftermath of shock, large-scale bloodshed and bitter division. Civil war, disrupted trade and bad harvests had made the late 1640s a grim time. When Cromwell died, his state had unified England, Wales and Scotland as a single entity, was united, prosperous, at peace, and had made itself respected abroad. At first his energies were absorbed in the subjection of Ireland and Scotland. In Ireland, where, in sacking Drogheda and Wexford, he permitted his troops to run amuck in a way he never did in Great Britain, he earned loathing. From January 1649, England was under the control of the 'Rump Parliament', watched over with increasing irritation and impatience by the army. The Rump's main object seemed to be its own preservation, and in this it was aided by the military leaders, whose principles demanded a general election and a new representative parliament, but who shrank from the prospect of the Anglican-royalist dominated assembly that was likely to result. On 20 April 1653, Cromwell took matters into his own hands. After a few blunt home-truths – 'Do you think to sit here till Doomsday come?' quoted a balladist – he brought a troop of soldiers into parliament, dissolved the Rump and sent the members home. From then on, though he attempted various forms of quasi-parliamentary government, his own presence at the head of affairs was the consistent and driving element in national life. The 'Barebone's parliament', composed of nominated members, one of whom, Praise-God Barbon, gave it its name, had a brief life in 1653.

In December of that year Cromwell assumed the title of Lord Protector. In September 1654 the first all-British parliament met, with English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish members; by Cromwell's own constitutional document, the Instrument of Government, he could not dissolve it for five months, but he did not wait a day longer. Its offence was to discuss the lord protector's role, rather than to govern as he wished it to. For eighteen months he ruled on his own, then in late 1655 he divided England into twelve military districts, each governed by a major-general with wide powers. This reminder that the army-paid for by substantial and efficiently collected taxes – was still in command caused widespread protest. Still experimenting, Cromwell called a third parliament in September 1656; by now his experience had taught him that only a partial reversion to traditional forms would bring long-term stability, and he planned a new Upper House. It was this parliament that offered him the crown. Though he refused it, in the knowledge that acceptance would split the army and bring more strife, the protectorship in its last phase was hardly distinguishable from a monarchy; it was even made hereditary.

The Great Seal of the Commonwealth The Great Seal of the Commonwealth: reverse

ENGLAND UNDER THE COMMONWEALTH

A famous later comment by Lord Macaulay said that the Puritans abolished bear-baiting, not because it gave pain to the bears, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators. With varying degrees of success, Cromwell's administration sought to curb the 'sinful' pleasures of old England, from maypole dancing to madrigal singing. It was easy enough to close a theatre: much more difficult to stop traditional seasonal fun and games in every village, vestiges of paganism though they might be.

But the Commonwealth allowed a wider range of religious practice than previous governments. The official religion of the state was severely Puritan. Everyone paid tithes to this nameless church, which occupied the place of Anglican Christianity without its liturgy. But no one was compelled to attend, or to swear to its tenets. Provided it was done discreetly, Anglicans, Anabaptists, even Catholics, were able to worship according to their own rituals or lack of them. Cromwell, who had stabled his horses and billeted troopers in some of the country's great cathedrals, had a wide tolerance of religious expression as long as it stayed outside of politics. During his rule, Jews were admitted to England for the first time since Edward I had expelled them in 1290; their arrival, along with the continuing inflow of Huguenots, played its part in the accelerating growth of London as the world's greatest trading city, overtaking Amsterdam.

The Commonwealth was an expensive state to administer. There had never been a standing army before; now it was 50,000 strong. The strength and size of the navy were also greatly increased. These were costs on top of the normal costs of government. But wealth was increasing. The restoration of peace encouraged the resumption of trade and manufacture. Evidence of this wealth can be seen in the foundation and enlargement of schools and the building of almshouses and hospitals. London, the seaport towns, the cloth towns, the mining and manufacturing districts (still small but densely populated) had always backed the parliamentary cause, and the rewards of peace were theirs to work for. Whatever else the Protectorate prohibited, it did not prohibit trade, enterprise, profit or education. Economic strength extended outwards. The Rump had begun a war against the Dutch in 1652, a new stage in the established struggle over control of the North Sea, of dominance in sea-trading, and in the establishment of colonies. Parliament and then the Commonwealth found an admiral in Robert Blake to rival the great Dutchman, Van Tromp. In 1649 Blake destroyed the fleet created by Prince Rupert and in doing so brought English naval power into the Mediterranean. Defeated by Van Tromp off Dungeness in 1652, he won a victory off Portland in 1654, and in a further victory off Texel, won by another general-at-sea, George Monck, Van Tromp was killed.

By 1654, the revitalised navy had established the position of mastery in the narrow seas which it was very rarely to lose again. When Cromwell made peace with Holland in 1654, Dutch concessions benefited English trade. In 1655 war was declared on Spain, and an English naval expedition captured Jamaica but failed to take Hispaniola, its prime objective. At Tenerife, Blake destroyed the Spanish fleet in April 1657. In the Commonwealth's dual foreign policy of protection and extension of English trade, and Cromwell's ambition to form a Protestant League, it was on the whole English interests that won. A treaty with France – where the Edict of Nantes still extended toleration to Protestantism – and joint attacks on the remaining Spanish holdings in the Low Countries, won the possession of Dunkirk. The Commonwealth, whose first envoys had been insulted and even murdered with impunity in European capitals, had made itself into a significant force in world affairs.

THE RESTORATION OF THE MONARCHY

The death of the Protector, in his fifty-ninth year, threw all his achievement into disarray. His son Richard, aged thirty-eight, named as his successor, was well-intentioned but not of his father's calibre, and had not grown up with the training, expectations and advice of an heir-apparent. Nor could he command the historic obedience given to a king.

The Great Seal of Richard Cromwell Richard Cromwell

At first he was backed by the army, but soon it was plain that the army commanders had conflicting views about the way forward. People who supported, or were working for, the accession of Charles II were pleased to see the army begin to disintegrate into factions, some supporting a return to the republican ideals of 1649, some looking for a generalissimo-figure to assume control. The parliament called by Richard was equally riven by contrary opinions, with many royalist sympathisers. He dissolved it in April 1659 and resigned his post, retiring to obscure country life. Casting about with a degree of desperation for a national authority with some claim to legitimacy, a military committee recalled the surviving members of the Rump Parliament so ignominiously dismissed by Oliver Cromwell. Forty duly appeared, to be blown hither and thither in their discussions by pressure from different generals, until one of the two most determined soldiers, John Lambert, forced its dissolution. While royalist demonstrations and local risings became more frequent, the other soldier, George Monck, commanding in Scotland, crossed into England with his army. Already in communication with Charles II and his advisers, he destroyed Lambert's efforts to resist his advance, and took control of London. Here he summoned, not the residue of the Rump again, but all the surviving members of the Long Parliament, as it was before Pride's purge. Monck was now in open negotiation with the exiled court at Brussels, but it was in the end this 'Convention Parliament' which, in May 1660, formally invited Charles, Prince of Wales and already King of Scotland, to assume his father's English crown.

Дата добавления: 2018-09-24; просмотров: 719;