Stuart England: Civil War and Commonwealth

THE STUART DYNASTY

The death of Queen Elizabeth, on 24 March 1603, was perceived as the end of an era, though in fact all the problems of her later years passed on unchanged and unresolved. But there was a new king, and a new dynasty. James Stuart, King of Scots, a sound Protestant and firm opponent of church rule in secular matters, was the choice of the Council as well as that of the old queen, and an attempt, known as the 'Main Plot', to substitute his first cousin, Arabella Stuart, never had a chance of success. James I installed himself as rapidly as possible, and in the twenty-two years of his English reign, made only one short return to Scotland. The opportunity which he himself perceived, and promoted, to form a united kingdom of Great Britain, fell on stony ground. Parliament could see little prospect of benefit in a union with Scotland and believed, mistakenly, that the old military threat from the north had been finally ended with the Union of the Crowns.

The Great Seal of James I James I

The kingdom which James inherited at the age of thirty-seven was very different to the one which he had reigned over since his babyhood. Despite their sharing a language, there had been little or no intercourse between England and Scotland. Edinburgh was as foreign a capital as Lisbon or Copenhagen. His new metropolis was the largest in Europe, a cosmopolitan warren, a seaport trading with the world, a centre of international commerce.

SHAKESPEARE AND ENGLISH CULTURE

In the course of Elizabeth's reign, there had been a great leap in the imaginative life. English drama had developed from something relatively crude and traditional, still showing its origins in medieval mummery, into a sophisticated entertainment which mingled, at its best, great poetry, dramatic action, exciting stories and a sharp awareness of contemporary politics and social life. During Essex's brief attempt to hijack the government in 1601, William Shakespeare's play Richard II had been performed – a play which openly discussed the possibility of replacing a king. London had purpose-built theatres and two theatre companies.

Though it is often now referred to as 'Shakespeare's England', the great playwright, much respected and admired as he was, certainly did not dominate it in anyway. His work characterizes England's spirit: in its exploration of what is most human and individual in us; its insistence on the dangers and ultimate failure of despotism; its expression of our subordination to a fate which we cannot direct or control but which by suffering, learning, understanding, we can still transcend. Shakespeare's underlying ideas retain their interest because they are still the fundamental themes of our own era five hundred years after him.

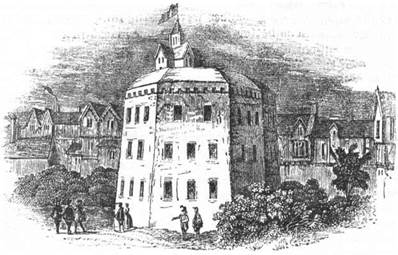

The Globe Theatre, London

In other ways he reflected his time, being a shrewd courtier and businessman, unlike his stormy fellow-dramatist Christopher Marlowe, killed in a tavern brawl, whose curtailed career foreshadows that of many later English poets. In modern England, such a man would undoubtedly be Lord Shakespeare, with a string of honorary degrees and other social distinctions; in Jacobean England, despite great and appreciated service with the King's Company, he retired, plain Mr Shakespeare, to his home town of Strat-ford-upon-Avon. Politics and warfare could make lords; the time of the artist was not yet come. Music was an important auxiliary in the English drama and at a high point in its own right. Church and secular music was composed in great quantity and widely admired throughout Europe. Singing was a national pastime, accompanying work as well as leisure.

Дата добавления: 2018-09-24; просмотров: 653;