middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 29 страница

| |||

| |||

Pergamon was also noted for its mosaics and was home to one of the more famous mosaicists of antiquity, Sosos, who was active in the second century bce. By this time a new mosaic technique was common that used small squares or tesserae (opus vermicula- tum), and the ability to work with a small size of tiles and a wider range of colors greatly expanded the potential for mosaics to be illusionistic (see the Alexander Mosaic in Figure 14.2). From the second half of the second century we can see the technique used in a mosaic from the House of Dionysos on Delos. This house has a peristyle central court with a mosaic in the center where it was part of an impluvium (Figure 14.29, page 372). In this position it would have been visually prominent to any visitor upon entering the house, rather than tucked away in a side room. Like many houses in Delos, there is no andron but several large rooms that would have been used for entertaining and leisure. Rather than places of domestic production like the houses at Olynthos,

Hellenistic houses became retreats for their owners and worth the investment of resources in their decoration.

As can be seen in the detail of the mosaic (Figure 14.30, page 373), it is made of small tesserae, some just 1 mm square, with blacks, whites, yellows, browns, and reds; the face and neck of the rider are in three-quarter view and modeled to a three-dimensional effect. The sharp turn of the feline head actually brings its gaze toward the southwest corner of the peristyle, the main point of entry into the courtyard from the street. A youthful figure riding a leopard should be Dionysos, and the subject would be appropriate as the house was located in the theater district of Delos, where a number of mosaics have theater motifs, including masks, muses, and Dionysos.

As can be seen in the detail of the mosaic (Figure 14.30, page 373), it is made of small tesserae, some just 1 mm square, with blacks, whites, yellows, browns, and reds; the face and neck of the rider are in three-quarter view and modeled to a three-dimensional effect. The sharp turn of the feline head actually brings its gaze toward the southwest corner of the peristyle, the main point of entry into the courtyard from the street. A youthful figure riding a leopard should be Dionysos, and the subject would be appropriate as the house was located in the theater district of Delos, where a number of mosaics have theater motifs, including masks, muses, and Dionysos.

However, there are some unusual elements in this mosaic: the figure is smaller in scale than is typical and has a pair of wings; the cat is more tiger than leopard in its markings. The winged figure also carries a branch or thyrsos, an attribute usually found with maenads, followers of the god. Indeed, the gender of the figure is somewhat ambiguous, as is its identity, and perhaps this reflects the syncretism of Greek and Levantine ideas and visual signs.

As floor decoration set in mortar, mosaics survive better than the painted walls of Hellenistic houses, but we can catch glimpses of small painted decoration in a few houses and larger paintings in some tombs like those from Vergina. Additionally, painted marble grave stelai were popular and a number have survived from sites like Alexandria in Egypt and Demetrias in northern Greece. Most of these stelai are conventional in their subject matter, showing the deceased either sitting on a couch or standing with an attendant or family member. One stele from Demetrias dating to around 200 все is remarkable for both its composition and subject matter, the Stele of Hediste, today in the Volos Archaeological Museum (Figure 14.31, page 374). The better preserved upper section of the panel shows a woman, Hediste, lying on a couch with her breasts bare above the blanket. She is seen in an angled view from above and behind her in profile view is her husband. Further back in space, cut off by the room’s door frame, is a nurse or midwife holding an infant. Even further back and perspectively smaller in scale is an attendant, whose open mouth indicates surprise, and some branches suggesting a courtyard or garden, creating three layers of a household interior. The tableau expresses quite vividly the grief of the household over the death of a young mother and her child.

The inscription at the bottom eloquently confirms this tragic situation and names both the Fates and Tyche as responsible for the deaths of mother and child:

The Fates spun out a painful thread from their spindles for Hediste, when she, as a bride, encountered childbirth.

The Fates spun out a painful thread from their spindles for Hediste, when she, as a bride, encountered childbirth.

Oh enduring is she, not intended to embrace her infant, nor even to water the lip of her own offspring with the breast.

One light looked upon them both and Tyche led them both into a single tomb, coming upon them indistinguishably. (Tr. Salowey 2012, 254)

The sway of Tyche over individuals speaks to the Hellenistic spirit, and the dramatic portrayal of reactions to Hediste’s death brings viewers into the experience, as we look on from the other side of the couch.

14.28 Stag Hunt mosaic by Gnosis from Pella, in situ, c. 330-300 bce. Central panel, 10 ft 2 VA in (3.10 m). Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

14.28 Stag Hunt mosaic by Gnosis from Pella, in situ, c. 330-300 bce. Central panel, 10 ft 2 VA in (3.10 m). Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

|

|

the private and personal realm

Smaller-scale works in bronze, gems, pottery, and terracotta would have been found in the private and domestic settings that we have just seen, as well as in sanctuaries as votive offerings and in tombs as offerings for the dead to console them in the afterlife. Cremation burial is more common during this period and some special wares are created as burial urns. The most elaborate of these were produced in south Italy and Sicily, with Centuripe vases, named for the Sicilian site where many were found, the most well known (Figure 14.32). Although these look like jars with lids, they are one-piece vessels and feature architectural moldings and acanthus leaves applied to the surface. They are brightly colored, often with a red background and figures painted in yellow, green, blue, and pink pastels. The scene here is a wedding with the bride surrounded by attendants bearing objects. The colors are applied to the vase after firing, creating an effect similar to fresco or painted stone. Highlights give a sense of volume to the figures, and the faces are in three-quarter view, giving further three-dimensionality to the bodies. Whether or not the urn was used for someone who was married or, like Phrasikleia, was a maiden who died before marriage is not certain from the object itself.

Smaller-scale works in bronze, gems, pottery, and terracotta would have been found in the private and domestic settings that we have just seen, as well as in sanctuaries as votive offerings and in tombs as offerings for the dead to console them in the afterlife. Cremation burial is more common during this period and some special wares are created as burial urns. The most elaborate of these were produced in south Italy and Sicily, with Centuripe vases, named for the Sicilian site where many were found, the most well known (Figure 14.32). Although these look like jars with lids, they are one-piece vessels and feature architectural moldings and acanthus leaves applied to the surface. They are brightly colored, often with a red background and figures painted in yellow, green, blue, and pink pastels. The scene here is a wedding with the bride surrounded by attendants bearing objects. The colors are applied to the vase after firing, creating an effect similar to fresco or painted stone. Highlights give a sense of volume to the figures, and the faces are in three-quarter view, giving further three-dimensionality to the bodies. Whether or not the urn was used for someone who was married or, like Phrasikleia, was a maiden who died before marriage is not certain from the object itself.

In Egypt, a special form of hydria were also used as a cremation urn. Called a Hadra hydria, this type of vessel is decorated with vegetal and pattern ornament drawn with black glaze on the cream surface (Figure 14.33). Mostly found in Alexandria, many of these bear inscriptions that show they were used for the remains of foreigners who died in Egypt. The inscription on this example tells us that it contains the remains of Hieronides of Phocaea, who died in 226-225 все leading an embassy to king Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246-221), giving us a rare precise dating for the Hellenistic period. The writing on these cinerary vessels suggests that they were meant to be seen after they were placed in the tomb. Interestingly, it has now been determined that the Hadra hydriai were not made in Alexandria but in Crete, and were exported to Egypt for this funerary use, another indication of the cosmopolitan quality of the Hellenistic period.

We saw in Chapter 11 that pottery continued to be produced in Athens in the third century and later after the end of red-figure ware, following metalware models and relying on more purely decorative motifs than figural scenes (see Figure 11.9, page 278). The so-called West Slope ware was exported and was one of several ornate, black-gloss wares like Gnathian ware that were produced in the Hellenistic period (see Figure 12.20, page 309 for a fourth-century example of Gnathian ware). Mold-made bowls with incised or relief decoration were produced in several areas of the Hellenistic world and are commonly called Megarian bowls (see Figure 11.10, page 279). These shapes imitate metal vessels, particularly Persian, and like metal work include both incised and relief decoration on their surface. Some, like the example from Athens, show one or more narrative scenes in a frieze, and sometimes include texts from poems to accompany the pictures. These wares, like plain pottery, could be found in both tombs and households.

We saw in Chapter 11 that pottery continued to be produced in Athens in the third century and later after the end of red-figure ware, following metalware models and relying on more purely decorative motifs than figural scenes (see Figure 11.9, page 278). The so-called West Slope ware was exported and was one of several ornate, black-gloss wares like Gnathian ware that were produced in the Hellenistic period (see Figure 12.20, page 309 for a fourth-century example of Gnathian ware). Mold-made bowls with incised or relief decoration were produced in several areas of the Hellenistic world and are commonly called Megarian bowls (see Figure 11.10, page 279). These shapes imitate metal vessels, particularly Persian, and like metal work include both incised and relief decoration on their surface. Some, like the example from Athens, show one or more narrative scenes in a frieze, and sometimes include texts from poems to accompany the pictures. These wares, like plain pottery, could be found in both tombs and households.

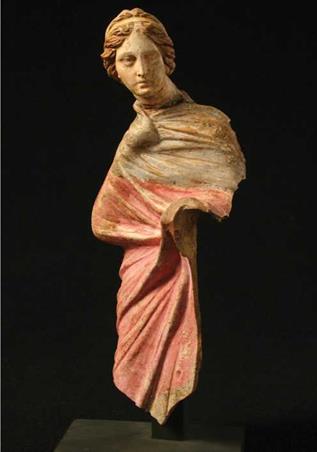

Terracotta figures continued to be produced in large numbers, and many of these served either as votive offerings in sanctuaries or as grave goods in tombs. Brightly colored figures of women were particularly popular and were appropriate subjects for the tombs of young women or offerings upon significant events like a wedding. Some of these, like the figure of a heavily draped woman found in a tomb in Taras/Taranto, vividly preserve their colors (Figure 14.34). Like marble portraits of women, the standing figures fall into several large types. This young woman has her right arm bent sharply upward, creating a sling out of her heavy mantle. The projecting and now missing left arm pulled the rest of the drapery sharply in the other direction, creating a very energetic pattern of drapery folds that animate what is still a standing figure. Like many Hellenistic statues, her head is turned sharply and her gaze, even at this small scale, is clear and focused. The pose is more animated than similar archaic and classical terracotta figures.

Terracottas like this are often called Tanagra figures generally, after the Boeotian site where many of them were first found in the nineteenth century, and became widely collected. These highly detailed and colorful figures were first produced in fourth-century bce

Terracottas like this are often called Tanagra figures generally, after the Boeotian site where many of them were first found in the nineteenth century, and became widely collected. These highly detailed and colorful figures were first produced in fourth-century bce

Athens, but their production spread to Boeotia; there were also significant production centers in Myrine (Anatolia), Alexandria, and southern Italy, including Taras/Taranto and Naples. In addition to standing women, Tanagras also included, among other subjects, actors and characters drawn from theater, dancers, children, and young girls playing. A terracotta showing a young child held in the lap by an old nurse is a charming and intimate scene that was a stock element of contemporary comedies (Figure 14.35). The faces, expressions, and proportions of the nurse and child are not idealized, and their large smiles suggest humor and delight. These and other terracottas show an interest in representing a wide range of character types, and can be associated with the rococo element of Hellenistic sculpture, like the dwarves from the Mahdia shipwreck (see Figure 14.13).

We saw in the introductory chapter an example of two seated women leaning together in an intimate conversation that is also characteristic of the genre (see Figure 1.6, page 10). The women do not have attributes, but could be a mother and daughter, perhaps Demeter and Persephone. Whether goddesses who protected young women or mothers, or simply women shown in an animated exchange, these were appropriate grave gifts or votive offerings for girls and young women and show them as vital and dynamic.

Dancers were also popular figures in terracotta and other media, including small bronzes like the Mahdia dwarves. One of the most unusual examples is a small bronze called the “Baker Dancer” in the Metropolitan Museum (Figure 14.36). The woman is wearing a heavy chiton with deep folds and has a thinner mantle wrapped over her body and head, making a veil. She pulls one corner of the mantle away from her body, which stretches the cloth to reveal the furrows of the chiton below in the drapery-through-drapery effect. We have already seen this feature in Tanagra-type figures; it also appears in marble sculpture and may have originated in the later third century bce. The dancer’s right arm is bent and enveloped in cloth to make a sling like the Taranto woman, but the pose here is much more complicated as the dancer is twisting her body toward her left while turning her head back toward the right, creating a pyramidal mass from some viewing points.

|

14.33 Hadra hydria, c. 226-225 все. 165/s in (42.2 cm). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 90.9.5. Urn of Hieronides of Phocaea. Photo: Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

|

14.34 Terracotta woman from Corso Umberto, Taras/Taranto, early 3rd cent. все. Taranto, National Archaeological Museum 112640. Photo: Museum.

|

14.35 Terracotta seated nurse holding child, late 4th cent. все. 4% in (10.8 cm). London, British Museum 1874,1110.18. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

|

14.36 “Baker Dancer,” 3rd-2nd cent. все. Bronze, 8 1/16 in (20.5 cm). New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art 1972.118.95. Photo: Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

These types of veiled dancers were popular in Alexandria and the bronze is said to be from Alexandria, although it is without a findspot. This type of figure is often found in terracotta, but this example remains unique in bronze work, and the quality of the bronze is fine and detailed. Whether this figure was for domestic viewing or, like her terracotta counterparts, made as a tomb or sanctuary offering, is uncertain, but it does capture the drama of dance and mime and gives a glimpse of the entertainment of elite courts and households.

A very small work combines many of the characteristics that we have seen in Hellenistic art, a gem set in a gold ring that is part of an ensemble thought to be again from Alexandria (Figure 14.37). The carnelian bezel is carved intaglio with a female figure leaning against a short column. She holds a cornucopia, an attribute of Tyche, but it is a double cornucopia and she holds a scepter as well. These link the figure to Arsinob II, as we saw earlier, making this figure signify not only a goddess, but also the divine nature of the Ptolemaic dynasty. The pose recalls also the Aphrodite of Melos (see Figure 14.17, page 362) and shares with her the exaggerated line of the hips to give the standing figure a more open pose, holding her attribute out toward the viewer. In an age in which individuals worried about the vagaries of Tyche, such a ring could serve as a talisman to protect its owner. The owner, too, could also express reverence for the Greek rulers of Alexandria and Egypt, and the hope of receiving prosperity from both gods and kings. This type of syncretism and symbolism is in keeping with the intellectual character of Hellenistic culture. The cornucopias are held out at some distance from the body, but the shoulders and head are set back, and the pose could suggest, at least to a modern eye, that they are only tentatively offered to a beholder, and could be snatched back in a moment. Even standing, we might see the figure as maintaining a dramatic tension, raising doubt as to the benefits conferred to any individual.

We saw in the last chapter that the Greek world and the production of art and architecture greatly expanded in the Hellenistic period to new sites such as Antioch, Pergamon, and Alexandria, and that Greeks ruled a diverse population in many parts of the Mediterranean and Near East until the Roman and Persian empires asserted control by the end of the first century. The scale of this expansion as seen in the size of the cities and the production of art is remarkable, but the interaction of the Greek culture with the other peoples of the Mediterranean and beyond is a continuous aspect of their history going back to the Bronze Age. In the second millennium, art from Minoan and Mycenaean palatial cultures was exported throughout the Mediterranean and materials and works from Egypt and the Near East were imported. Even through the so-called Dark Ages contacts with Cyprus and other sites continued at some level, and in the later eighth century the new Greek poleis began sending colonists to start new cities throughout the Mediterranean. In the seventh and sixth centuries Greek art was exported thousands of miles from Spain to the Crimea and was produced outside the boundaries of mainland Greece in Magna Graecia.

In other words, Greek art did not exist in isolation and one should consider that the cultures of the ancient world were in continuous communication and exchange with one another, sometimes through war and conquest, sometimes through trade and migration, and often through both. Whereas some early histories of Greek art tended to see it as self-generated, springing as it were full- grown like Athena out of the head of Zeus, Greek art and culture were engaged in dialogue with other cultures, influencing and being influenced through the reciprocal contact. To conclude our exploration of Greek art history, we should consider briefly the interaction of Greek art and culture with those of its neighbors, and with our own culture today.

The three vessels in Figure 15.1 were found in 1890 in a tomb in Athens, along with seven other vases, including the cup in Figure 10.22 (page 258). Based on the style of the figural pottery, the works are dated around 460-450 все and came from one or possibly two closely related workshops associated with the potter Sotades, who signed the phiale on the right Sotades epoie, “Sotades made [me].” The sides of the pots have been carefully worked to create precise series of concentric flutes from the rim to the bottom. The flutes have been painted with three colors, black, white, and a matt red slip; the edges of the flutes are abraded and show the natural red of the clay. The mastoid cup shape, named after its resemblance to the breast, began to appear in Attic pottery in the late sixth century but its origins are thought to derive from metal cups of similar shape used in Near Eastern, especially Persian, dining. The drinkers would hold the vessel supported by the fingertips while reclining on a couch. The phiale is also a shape that derives from Near Eastern prototypes and was established in the Greek pottery repertory in the sixth century. The function of the vessel, however, was different from its model. In the Near East it served as a drinking cup like the kylix or mastoid cup, but in Greece the phiale became a ritual vessel for pouring offerings of wine onto an altar or the ground (see Figure 9.18, page 232).

| |||

| |||

Most Greek examples of the shapes do not include the fluting seen here, which imitates the fluting found in Persian metalwork, like the rhyton in Figure 15.2. This object serves as a funnel, with wine poured into the top and then flowing out of a hole at the base for pouring into the cup of the drinker. It is a luxury service item in Near Eastern dining, and this example preserves the decorative fluting and use of gilding to create a high-status work to be used in a gathering of elite members of the Persian

empire. In comparing color and decoration to the mastoids and phiale of Sotades, one can see how art historians have thought that the Greek potter was imitating the shapes and effects of Persian metalwork in Attic clay.

empire. In comparing color and decoration to the mastoids and phiale of Sotades, one can see how art historians have thought that the Greek potter was imitating the shapes and effects of Persian metalwork in Attic clay.

In considering the relationship of the Sotades pots to Persian metalwork, one needs to examine not only the artistic details that suggest a connection, but also the motivation, as Margaret Miller has explained, both for the artist and for the family who purchased the works to serve as grave goods (Miller 1997). First, one can consider whether works like the Sotades cups are imitations, within the limitations of using a different medium, or adaptations. An imitation follows closely the shape and details of the model, whereas an adaptation would involve more significant changes to the shape and form of the model, perhaps using selected details out of context or using the model for a different purpose to create a hybridized work. With both imitation and adaptation, one has to ask whether the “copy” is meant to enhance the prestige or power of the owner/user or to denigrate or neutralize the status of the model and its culture, or some range or combination of motives.

In the case of the Sotades cups, we should probably consider these as imitations since the function and shape of the mastoid cup have not changed significantly, and creating the fluting is an added level of work and not a technique typical of ceramics, unlike metalwork. Even if the function of the Greek phiale is different from its Near Eastern prototype, in this case it is still imitation rather than adaptation, which would require greater change to the model. For example, Greek potters also produced animal-shaped rhyta similar to the Persian example, but transformed their pottery versions into closed vessels for drinking rather than a funnel for pouring. Sometimes stands were added, further adapting the original to the requirements of sympotic drinking. Whereas the sym- posion at its beginning imitated luxury Near Eastern dining, by the fifth century it was a more widespread custom and adapted to the ideology of the polis. The kylikes from the Agora well (see Figures 1.10A and 1.10B, page 14) that were introduced in the first chapter show that the practice remained formal, but was not elitist as it had been originally.

In both imitation and adaptation, the motivation can be quite varied. Metalware vessels were prestige objects, both for their intrinsic material value and for their associations with elite cultural groups such as Persian nobility. The Sotades cups, while not as valuable as metalware, were yet special and distinctive products that would have been recognized as such by family and participants in the funerary ritual. Their display and deposit at the tomb would proclaim the status of the deceased, just as imported work had done in the tomb of the Rich Lady (see Figure 4.6, page 76).

Elsewhere we have other evidence of the adaptation of Persian art and style in Greek art, such as the kanephoros shown in the procession to Apollo on the fifth-century krater by the Kleophon Painter (see Figure 7.17, page 174). She wears a sleeved garment, the chitoniskos, that is unlike the sleeveless peplos or chiton/himation garments seen in Greek painting and sculpture. There is also a fringe at the edge of the garment below the knee, another characteristic of Near Eastern textiles. The motifs on the garments, however, have been adapted, including the stylized birds above the fringe. Overall, her garment is modeled on the sleeved tunic but the decoration has been adapted for Greek use. The Persians were a powerful empire with many allies and contacts among the Greek poleis, and their art could be sources of emulation for enhancing the prestige of Greeks owning imitations or adaptations.

We can see another example of the complexity of the Persian and Greek artistic relationship by turning to the Persian palace at Persepolis. The Achaemenid empire had been founded in 557 все by Cyrus the Great (d. 530), who captured Babylon in 539 and from there extended his control to the Levant and Anatolia. His successor Cambyses (r. 530-522) extended the empire to Egypt by 522, followed by Darius (r. 522-486) into eastern Europe, including Thrace and Macedonia. Around 515 Darius founded the palace at Persepolis as one of the capitals of the Persian empire. The most prominent feature of the complex was the Apadana or audience hall (Figure 15.3). This building had a nearly square base rising almost 4 meters above the flanking courtyards. Access to the Apadana was through a monumental gate leading into the courtyard, but the path followed a bent-axis organization involving a number of turns or switchbacks along the way, rather than a straight processional path. The Apadana served as a place where the subject territories of the empire would bring their tribute to the King of Kings. The stone staircases, parapets, and podium walls of the Apadana were carved with reliefs whose subjects included palace guards, processions of tribute bearers, and images of lions attacking bulls, as can be seen in the picture of the east stairway. The visitor to the palace would be reminded at every step, turn, and stop of the power of the Persian king.

|

The use of reliefs in palaces had ample precedent in the Assyrian empire, as the guardian figure in Chapter 6 demonstrated (see Figure 6.2, page 133), but the use of limestone and other hard stone at Persepolis indicates a more ambitious and difficult decorative program, as was the design of the Apadana. The ceiling of the audience hall was a hypostyle structure, supported by thirty-six tall stone columns with capitals, creating an interior space that was almost 60 meters square. The height and volume of the Apadana were unprecedented in ancient architecture and signified powerfully the ambitions of the Achaemenid kings.

As was true of Greek sculpture and architecture in the seventh century все, there was no established tradition of precision stone cutting and carving in Persian art and architecture in the sixth

century when the building program began. To build their palaces, Darius and other Persian kings drew upon the expertise and materials of their subject nations, creating in the process a multicultural workforce. An inscription of Darius at the Achaemenid palace at Susa in Persia, which also included an Apadana, tells us that the workers who built that structure included several conquered peoples from Anatolia, and specifically that “The stone-cutters who wrought the stone, those were Ionians and Sardians” (Frankfurt 1970, 349). If we compare the carving style of the reliefs at Persepolis to late sixth-century relief sculpture from Greece, such as the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2, pages 183, 184), one can readily see similarities in the rendering of the features that support Darius’s claim that Ionians were cutting and carving stone for the Persian palaces. The spacing and posing of the Persepolis figures are more formal than the narratives of the Siphnian Treasury, as would be suitable for their different purpose. One interesting point of comparison is the lion attack motif at Persepolis and in Greek art, and its adaptation in the lion attacking a giant on the Siphnian Treasury (see Figure 9.1, page 212). In most of these, the lion and victim are shown in profile, but the twist of the lion’s head as it bites into a bull or giant presents an artistic problem of foreshortening that was not fully resolved in the sixth century, as the Siphnian Treasury shows. In both cases we end up with a combination of a frontal and elevated view of the lion’s face, a profile body, and the use of the mane to mask the turning of the neck.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1012;