middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 24 страница

Ridgway, B. S. 1997. Fourth-Century Styles in Greek Sculpture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. D. 2014. “Desirability and the Body.” In T. K. Hubbard, ed. A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities, 31-53. Malden, MA/Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Tanner, J. 2013. “Figuring Out Death: Sculpture and Agency at the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of the First Emperor of China.” In L. Chua and M. Elliot eds. Distributed Objects: Meaning and Mattering after Alfred Gell, 58-87. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Tomlinson, R. A. 1983. Epidauros. Austin: University of Texas Press.

further reading

Ajootian, A. 1996. “Praxiteles.” In O. Palagia and J. J. Pollitt, eds. Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture. Yale Classical Studies 3, 91-129. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boardman, J. 1995. Greek Sculpture: The Late Classical Period and Sculpture in Colonies and Overseas. London: Thames and Hudson.

Franks, H. M. 2012. Hunters, Heroes, Kings: The Frieze of Tomb II at Vergina. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

Marvin, M. 2008. The Language of the Muses: The Dialogue between Roman and Greek Sculpture. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Mattusch, C. C. 2004. “Naming the ‘Classical’ Style.” In A. P. Chapin, ed. Charis: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr. Hesperia Supplement 33, 277-291. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Ridgway, B. S. 1997. Fourth-Century Styles in Greek Sculpture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ridgway, B. S. 2001. Hellenistic Sculpture I: The Styles of ca. 331-200B.C. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Trendall, A. D. 1989. Red Figure Vases of South Italy and Sicily. London: Thames and Hudson.

identity

Timeline Gender Women’s Lives Women in Public

Men and Youths: Gender and Sexuality Interaction: Class, Civic, and Ethnic Identity Textbox: Money Purses, Sex, and Identity

References Further Reading

timeline

| Sculpture | Pottery and Painting | |

| 900-700 | “Boots Grave” in Athens, 900 Dipylon amphora and krater, 760-735 [4.7, 4.9] Thebes bowl, 730-720 [4.23] | |

| 700-600 | Kore of Nikandre, 650-625 [6.3] | Chigi olpe, 650-640 [6.11] |

| 600-480 | Lakonian mirror, 560-540 Kore of Phrasikleia, 550-540 [8.13] | Panel from Pitsa, 540-530 [8.21] Kylix with symposion scene, 520 |

| 480-400 | Grave stele of Ampharete, 430 [10.19] Grave stele of Hegeso, Koroibos-Kleidemides family, 400 [5.28] | Kylix with male courtship, 480 Krater by Niobid Painter with departure, 460-450 [9.18] Pyxis with wedding procession, 440-430 Lebes with domestic scene, 430-420 Chous with girl, 430-420 Grave goods from Metaponto, 425-385 |

| 400-330 | Dexileos Monument, 394/3 [12.12] Grave stele of Mnesitrate, 350 | Campanian hydria with ritual procession, 350-330 |

| 330-30 | Statue of Aristino§, 3rd cent. Grave stele of Phila, 2nd cent. |

| L |

ooking at the kylix in Figure 13.1, we can compare its red-figure technique to the calyx krater by Euphronios (see Figure 8.26, page 206). The rendering of anatomical features such as the eyes and the attempt to show two bodies in a complicated and intertwined action are characteristic of the style of the Pioneers at the end of the sixth century bce. Turning to the subject, we can see that is a symposion (see Chapter 5), with a youth reclining on a couch with cushion and a young woman reclining against him, holding an aulos with which she had been providing musical entertainment. The picture is an excerpt from a group activity like the symposion scenes we have already discussed (see Figure 5.21, page 120; Figure 10.20, page 255), and may have taken place in the andron of a house (see the reconstruction of a public andron in Figure 5.20, page 119). As a drinking cup, the representation of a sympotic scene on its interior would provide the drinker with a picture of a symposion while he drank from it. The picture, then, nicely aligns the function of the vase with its decoration and setting.

We can consider the scene beyond its style and sympotic subject, since it also represents two people whose individual and social identities differ. The young woman, for example, is either a slave or a hired entertainer for the event, placing her in a different social class than the young man, who is a guest at the symposion. There is also a difference in gender between the two figures, not just in terms of their biological sex, but also in the relationship between men and women. His nudity is not unusual, as we have seen throughout the history of Greek art, but her nudity, a century and a half before the Aphrodite of Knidos, is strikingly different. He wraps his right leg around her hips and his right arm around her head, essentially controlling her like a wrestler, but fondling her breast and bringing her face close; he clearly has a sexual intent. Her reaction to the situation is more ambiguous. The right arm holding up the aulos suggests surprise, but she also reaches behind his head as if to pull him closer while her body and head twist around. Whether she was hired for both musical and sexual entertainment at a symposion, or was a slave who essentially had to submit to her owners whims is not certain, but it is not likely that he would behave this way if she were his social equal. The necklace or collar that she wears is unusual and has been identified as the Egyptian Broad Collar, which consisted of rows of beads and tubes in a semi-circular shape (Cole 2013). With her shorn hair, these markers suggest that she is a foreigner and likely an Egyptian or perhaps an Egyptianizing Ionian Greek, introducing a level of ethnic identity to the mixture of social class, sexual, and gender issues in the scene.

On one level images such as this might appear as everyday genre scenes. They are, in fact, staged pictures that express the complex web of identities of the artists and viewers who used, owned, and

13.1 Attic red-figure kylix attributed to the Gales Painter or the Thorvaldsen Group, 520 bce. Diameter 8% in (22.3 cm). Symposion scene. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Rebecca Darlington Stoddard, 1913, 1913.163. Photo: Yale University Art Gallery.

13.1 Attic red-figure kylix attributed to the Gales Painter or the Thorvaldsen Group, 520 bce. Diameter 8% in (22.3 cm). Symposion scene. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Rebecca Darlington Stoddard, 1913, 1913.163. Photo: Yale University Art Gallery.

looked at the objects and their images. We will explore these different aspects of identity in this chapter, beginning with gender. In doing so, we should consider how visual elements mark identity. In pictures, we can look at signs such as hair, clothing, and attributes that mark the identity of the

figure for the viewer; such an image presents a construction of identity through this combination of signs. At another level, though, we can consider that the works themselves are chosen by individuals and so can express identity by their selection, whether through the image on an object like a kylix or grave stele or through its function. If a cup like the Yale kylix, for example, were purchased for a symposion in Athens, it would be used by a man. By selecting it, the user would act as an agent and be expressing his identity through the use of the cup. If the cup were bought and used by an Etruscan, however, its use and meaning for identity might be different. The identity signified by the image and by the actions of the viewer may vary, then, as the context and agent changes.

figure for the viewer; such an image presents a construction of identity through this combination of signs. At another level, though, we can consider that the works themselves are chosen by individuals and so can express identity by their selection, whether through the image on an object like a kylix or grave stele or through its function. If a cup like the Yale kylix, for example, were purchased for a symposion in Athens, it would be used by a man. By selecting it, the user would act as an agent and be expressing his identity through the use of the cup. If the cup were bought and used by an Etruscan, however, its use and meaning for identity might be different. The identity signified by the image and by the actions of the viewer may vary, then, as the context and agent changes.

gender

In discussing gender in art, we first have to distinguish between biological sex, gender, and sexuality. Biologically one is typically born either male or female, although there are some individuals with more ambiguous sex type. Most of these differences relate specifically to reproduction, so that childbearing and nursing are biological functions that women carry out based on their biological sex. The vast majority of human anatomy is similar in both women and men, but some external anatomical differences, such as genitals and breasts, provide immediate visual cues to an individual’s biological sex. There are in addition secondary sexual characteristics, such as beards and baldness, that are also visually distinctive by sex.

Childrearing, as opposed to childbearing and nursing, is a socially defined task that, while falling on women in most cultures, is not biologically determined. The term gender signifies a second aspect of identity and encompasses the social roles and relationships of men and women, including childrearing, fighting, labor, and production, as we shall see in this section. The third component of identity, sexuality, is the orientation of sexual behavior toward individuals of the same or opposite sex, or to both sexes. We will look at representations of sexuality in a later section of the chapter.

Gender, then, is the social definition or translation of sexual differences. While it may overlap with biological sex, gender definitions and roles will vary considerably from one culture to another. Clothing, activities, physical location, legal and political rights, education, and cultural opportunities may all serve to distinguish one gender from another. We can turn to the fourth-century grave stele of Mnesistrate to consider the visual manifestations of gender (Figure 13.2). The beard is a biological marker that identifies the figure on the right as a man. As we have seen in previous chapters, the

beard is also a social indicator of maturity, of full legal rights and citizenship, so it is not simply a biological marker. Men can start growing a beard in their late teens, but the presence of a beard here signifies that the man is the head of a household, either the husband or father of the other figure, and is a mature citizen, thirty or more years old.

Since men can be clean shaven, either in reality or in art, there are other ways of visually distinguishing gender through hairstyle and clothing. Adult Greek men generally have shorter hair than adult women, although women’s hair is frequently tied up or covered like that of the woman Mnesistrate on the left. Younger men and women often have longer, hanging hair, so Mnesistrate’s hairstyle suggests she is an adult like the man, although there may be a wide difference in terms of their actual age. The clothing of the figures also differs. The man, who is not named, wears a long himation draped over one shoulder and falling at the calves, while Mnesistrate wears two garments, a thin, full-length chiton and a himation draped over both shoulders and the back of her head. Women are typically more heavily covered than men, and this reflects differing social conventions regarding the display of the body and modesty, or aidos, a term that can also suggest shame. Even when wearing a single garment like the peplos, as in the classical caryatid mirror (see Figure 10.6, page 242), its heavier fabric provides a similar or greater degree of covering than the chiton and himation.

Since men can be clean shaven, either in reality or in art, there are other ways of visually distinguishing gender through hairstyle and clothing. Adult Greek men generally have shorter hair than adult women, although women’s hair is frequently tied up or covered like that of the woman Mnesistrate on the left. Younger men and women often have longer, hanging hair, so Mnesistrate’s hairstyle suggests she is an adult like the man, although there may be a wide difference in terms of their actual age. The clothing of the figures also differs. The man, who is not named, wears a long himation draped over one shoulder and falling at the calves, while Mnesistrate wears two garments, a thin, full-length chiton and a himation draped over both shoulders and the back of her head. Women are typically more heavily covered than men, and this reflects differing social conventions regarding the display of the body and modesty, or aidos, a term that can also suggest shame. Even when wearing a single garment like the peplos, as in the classical caryatid mirror (see Figure 10.6, page 242), its heavier fabric provides a similar or greater degree of covering than the chiton and himation.

Hair and clothing are culturally specific and need to be interpreted by ancient Greek standards. For example, men can also wear full-length chitons like Mnesistrate. The adult figure folding the peplos from the east Parthenon frieze is a male priest, wearing a long chiton as a religious marker (see Figure 10.15, page 250), as does the figure of Zeus standing between Apollo and Herakles in the Siphnian Treasury (see Figure 8.1, page 183). The fourth-century Amazons at Epidauros (see Figure 11.1, page 270) and Halikarnassos (see Figure 12.9, page 297) wear a short chiton that to a modern eye looks like a woman’s dress, but was actually a garment worn by Greek men, especially warriors, as can be seen in the Niobid krater (see Figure 10.22, page 258) and the Parthenon frieze (see Figure 1.1, page 2). For a contemporary Greek viewer, the Amazons were clearly cross-dressing even without armor, transgressing the visual boundaries marking male and female appearance and gendered behavior. Men, too, could also adopt female clothing, as male actors did playing female roles and as Spartan husbands did when furtively leaving the army barracks to visit their wives at home.

Beyond clothing, there are visual signs that women are in a secondary position to men socially. The virtual nudity of the sympotic couple in Figure 13.1 may be equivalent, but their actions, with the youth controlling and limiting her movement, place the woman in an inferior physical position. She does not act in the modest and restrained manner of Mnesistrate. There are a number of such scenes in Greek art, especially in sympotic pottery painting, and there has been debate about whether a woman in such a scene is a porne, or prostitute, or a hetaira, a woman hired to provide entertainment and possibly sex as well. Literary sources suggest that respectable women avoided contact with men who were not their close relatives, leading to the use of the term hetairai in scholarship to label women in scenes like the Yale kylix. This label is frequently applied to women in scenes where they simply converse with men, who may offer them small gifts or hold small pouches that probably contained coins. If they are hetairai, the discussions in these circumstances would be about the services they will provide at an event, but we will see in the textbox for this chapter that the meaning of money purses is not certain.

Beyond clothing, there are visual signs that women are in a secondary position to men socially. The virtual nudity of the sympotic couple in Figure 13.1 may be equivalent, but their actions, with the youth controlling and limiting her movement, place the woman in an inferior physical position. She does not act in the modest and restrained manner of Mnesistrate. There are a number of such scenes in Greek art, especially in sympotic pottery painting, and there has been debate about whether a woman in such a scene is a porne, or prostitute, or a hetaira, a woman hired to provide entertainment and possibly sex as well. Literary sources suggest that respectable women avoided contact with men who were not their close relatives, leading to the use of the term hetairai in scholarship to label women in scenes like the Yale kylix. This label is frequently applied to women in scenes where they simply converse with men, who may offer them small gifts or hold small pouches that probably contained coins. If they are hetairai, the discussions in these circumstances would be about the services they will provide at an event, but we will see in the textbox for this chapter that the meaning of money purses is not certain.

Aidos was expressed not only through clothing, but also by the way that individuals looked at their surroundings and other people. Women were expected to lower their gaze when in public or mixed company, since their glance could be sensually exciting and provocative to a man. This lowering of the gaze, seen even in the slightly downturned heads and eyes of some of the idealized mirror caryatids, is said to signify a sense of shame as well as modesty in women. Young men, too, who might be displayed before the public eye when being crowned as athletic victors, were also expected to lower their gaze with modesty and not look directly at the crowd, even while the spectators were looking at them with admiration and even desire.

It is interesting, then, that on her grave stele Mnesistrate looks directly at the man before her. Their missing right arms might have been joined in a handshake associated with departure and farewell, a gesture frequently found in funerary monuments. Of greater interest is that she also raises her left arm as if she were speaking to the man, giving her the more active role in the scene. While Mnesistrate is clothed appropriately for a respectable, elite woman, her behavior suggests an equivalence with the man and is a reminder that gender relationships have more variation in practice than the limited range of literary sources, mostly written by elite men for each other, would suggest. That only her name is written on the stele indicates that this is her grave monument; her actions and the monumental scale give Mnesistrate a striking social prominence.

It is interesting, then, that on her grave stele Mnesistrate looks directly at the man before her. Their missing right arms might have been joined in a handshake associated with departure and farewell, a gesture frequently found in funerary monuments. Of greater interest is that she also raises her left arm as if she were speaking to the man, giving her the more active role in the scene. While Mnesistrate is clothed appropriately for a respectable, elite woman, her behavior suggests an equivalence with the man and is a reminder that gender relationships have more variation in practice than the limited range of literary sources, mostly written by elite men for each other, would suggest. That only her name is written on the stele indicates that this is her grave monument; her actions and the monumental scale give Mnesistrate a striking social prominence.

womens lives

| |||

| |||

In order to place artistic representations of women into context, we need to consider the stages in a woman’s life. The Greeks used the word pais (pl. paides) to refer to both boys and girls. Both were essentially viewed as immature adults who had to develop physically and intellectually to take on their adult roles. Gender distinction began at birth, with an olive wreath hung at houses for a newborn boy and wool for a girl, if she were accepted into the family and not left exposed after birth to die, a not uncommon fate. While the number of representations of young boys, under age five, is greater in Greek art than that of girls, the activities of boys and girls are similar, including scenes of play and pretending to do adult activities. One large source of such images is on the small wine pitcher called a chous (pl. choes), which was used in the Dionysiac festival of the Anthesteria that celebrated the opening of the new wine from the fall harvest. The pitchers were actually used as drinking vessels, and small versions were made for children to carry and use. In the chous from a grave in the Kerameikos cemetery (Figure 13.3), we see a girl in a long chiton (the standard costume of a charioteer) driving a small cart pulled by two deer. Deer are sacred to Artemis, who was a patron of unmarried girls, and goddesses

such as Artemis and Athena are shown driving chariots in mythological pictures. Amazons, too, could drive chariots, but modeling the behavior of a goddess in this image suggests a more appropriate form of childhood play and mimicry.

Between five and seven years, children began to learn the tasks and roles that they would need at maturity. For girls, this included the many preparatory tasks associated with weaving. As we saw in Chapter 5, wool-working and weaving were a primary task of Greek women and this role is acknowledged early, with objects like the spindle becoming symbols of that domestic gender role. There were also important roles in religious ritual that would introduce girls to the community as they approached puberty. The comic poet Aristophanes mentions some of these pertinent to Athens in his play Lysistrata, when the chorus of women states:

Once I was seven I became an arrephoros [bearer of sacred vessels].

Then at ten I became a grain grinder for the goddess [archegetis].

After that, wearing a saffron robe, I was a bear [arktos] at Brauron.

And as a lovely girl [pais kale] I once served as a basket-bearer [kanephoros], wearing a string of figs.

(Lysistrata 641-647; tr. Fantham et al. 1994, 84)

Each role assumed more responsibility in the performance of ritual, and the last is one of the most prominent duties, bearing the basket of implements used in the ritual sacrifice. The Attic krater showing a Delphic procession in Chapter 7 shows an elaborately dressed kanephoros at the head of the procession, standing before the sacred tripod and omphalos of Delphi (see Figure 7.17, page 174), and the two girls behind the priestess in the Parthenon frieze may be arrephoroi (see Figure 10.15, page 250). The rituals and roles would vary by region, but in each case the succession of rituals would ultimately present the young women of a town carrying out some of its most important rituals just as they reached the age of puberty. Aristophanes uses the word pais to describe the kanephoros, but we can also use the word kore or maiden for this figure, the term that has been applied generically to the statues of young women.

After puberty, around age fifteen in Athens but several years later in Sparta, a young woman would be married, becoming a nymphe or wife. Her husband was usually much older, about thirty, after he had achieved full legal rights and become head of an oikos. The marriage ritual served to mark publicly this change in status for both bride and groom. Typically the groom would go to the house of the bride, lead her from it to his cart or chariot, and then, accompanied by a retinue, bring the bride to his house with her belongings. A number of wedding scenes are shown on black-figure and red-figure pottery, such as a red-figure pyxis in the British Museum (Figure 13.4). On the rolled-out picture that wraps around the cylinder, we see on the left a procession bearing the bride’s goods and a torch-bearer following the chariot. The bride, with her mantle over her head but her face exposed, stands in the cab while the groom mounts to drive her to his home. A man leads the way to a set of double doors with one panel open; this serves doubly as the destination and the departure, and the woman inside could be the mother of either bride or groom, but since she looks to the right, she is more likely the bride’s mother watching her daughter leave. One unusual feature of this scene is that the groom is beardless, and so by normal visual convention a man who is not a full adult over thirty years of age. Most grooms in wedding scenes are bearded, but in the late fifth century все and afterward beardless grooms begin to appear more frequently in painting, often on ritual vases or objects used by women such as this pyxis. Since marriage was closely tied to property ownership, the change in appearance of the groom in the picture does not suggest a dramatic change in the reality of marriage.

After puberty, around age fifteen in Athens but several years later in Sparta, a young woman would be married, becoming a nymphe or wife. Her husband was usually much older, about thirty, after he had achieved full legal rights and become head of an oikos. The marriage ritual served to mark publicly this change in status for both bride and groom. Typically the groom would go to the house of the bride, lead her from it to his cart or chariot, and then, accompanied by a retinue, bring the bride to his house with her belongings. A number of wedding scenes are shown on black-figure and red-figure pottery, such as a red-figure pyxis in the British Museum (Figure 13.4). On the rolled-out picture that wraps around the cylinder, we see on the left a procession bearing the bride’s goods and a torch-bearer following the chariot. The bride, with her mantle over her head but her face exposed, stands in the cab while the groom mounts to drive her to his home. A man leads the way to a set of double doors with one panel open; this serves doubly as the destination and the departure, and the woman inside could be the mother of either bride or groom, but since she looks to the right, she is more likely the bride’s mother watching her daughter leave. One unusual feature of this scene is that the groom is beardless, and so by normal visual convention a man who is not a full adult over thirty years of age. Most grooms in wedding scenes are bearded, but in the late fifth century все and afterward beardless grooms begin to appear more frequently in painting, often on ritual vases or objects used by women such as this pyxis. Since marriage was closely tied to property ownership, the change in appearance of the groom in the picture does not suggest a dramatic change in the reality of marriage.

Looking at the wedding scene, one can compare it to scenes of maidens being abducted by gods and heroes, such as the abduction of Persephone at Vergina (see Figure 12.25a, page 315). In a slightly different form, it also resembles the man leading a woman onto a ship on the Geometric bowl from Thebes (see Figure 4.23, page 94). In one sense, the wedding procession is a ritualized abduction that reminds the viewer that the bride has lost her home and family. In another sense, chariots are also markers of status that elevate the wedded pair as they process through the town.

13.4 Attic red-figure pyxis attributed to the Marlay Painter, 440-430 все. 6n/i6 in (17 cm) high (with lid). London, British Museum 1920,1221.1. Wedding procession. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

13.4 Attic red-figure pyxis attributed to the Marlay Painter, 440-430 все. 6n/i6 in (17 cm) high (with lid). London, British Museum 1920,1221.1. Wedding procession. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

|

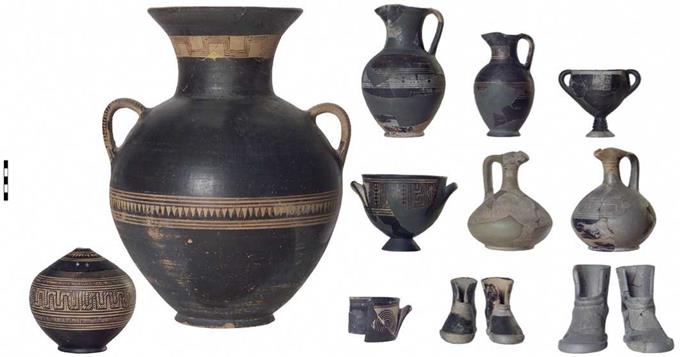

13.5 Early Geometric grave goods from a burial (D16:2, “Boots Tomb”) in the Agora, Athens, 900 все. Athens, Agora Museum.

Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

13.5 Early Geometric grave goods from a burial (D16:2, “Boots Tomb”) in the Agora, Athens, 900 все. Athens, Agora Museum.

Photo: American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

|

The wedding, therefore, marked a visible but complex transition in identity and status. The inscription on the base of the kore of Phrasikleia (see Figure 8.13, page 195) makes it clear that she died before she could marry, but her statue gives her the perpetual identity of the bride for the visitor to her tomb. In addition to taking on a new identity by the drive to her husband’s house, there were also personal items, such as mirrors and shoes, that were surrendered and offered at

sanctuaries to mark the transition from childhood to maturity. Susan Langdon, for example, has suggested that the two pairs of terracotta boots found in the Early Geometric “Boots Grave” in the Athenian Agora (Figure 13.5) were not intended to speed the journey of the dead to the afterlife, but marked the childhood boots given up by a woman on her marriage (Langdon 2008, 134-137). Shoes and clothing like these were dedicated by brides at shrines to Artemis. Perhaps the deceased in this tomb died before marriage, but the model boots were given as grave goods as signs of a mature identity.

Following the procession to the husband’s house, the bride would receive guests in her new quarters.

Following the procession to the husband’s house, the bride would receive guests in her new quarters.

Mythological versions of the scene are found on the Francois Vase, where Peleus and Thetis receive the gods at their home, with Peleus outside and Thetis inside, partly hidden by the door (see Figure 8.23, page 203). The epinetron by the Eretria Painter (see Figure 10.24, page 260), a device worn over the knee to protect against abrasion and cuts from working with wool, shows the mythological epaulia of Alkestis, where she received her friends and family in her new home. Once established, the new wife was responsible for taking on the management of the house and its provisions, supervising slaves and work such as the production of textiles, and ultimately bearing a child, preferably male, to continue the line of the oikos. There are many domestic scenes on painted pottery that symbolize this activity, such as a red-figure lekythos in Boston (Figure 13.6). Here a fully dressed woman sits on a chair with a kalathos in front of her, from which she pulls the heavy strand of wool through her hands.

On such a narrow shape, the full representation of all weaving activities would be difficult, and there would be little room for a loom such as we saw in other pictures (see Figure 5.19, page 118; Figure 9.12, page 226). The kalathos, the spindle, and the strand of wool become metonyms for the entire process of textile production in the Greek household.

A sakkos, or net bag that mature women often use to tie up their hair, hangs behind her from a background wall, as does a mirror, similar to caryatid mirrors, with a profile engraved on its back side. The diadem and earrings suggest that this is a mature or married woman, but the inscription reads “he pais” or “the [girl] child.” Greek artists did not frequently distinguish fully grown women by age, so that a young maiden of fourteen, a wife of twenty, and a mother of thirty or forty years usually look alike; the picture represents an idealized picture of all women. This lekythos was used for grave offerings and ritual, which may explain the inscription. Like Phrasikleia, artists represented individuals not as they were, but as they strived to be. A leky- thos like this could be an offering for a girl who died before marriage or for a woman who had been a wife, but the image serves to idealize either. The vase is said to have been found in Gela, Sicily, and it was undoubtedly a good strategy of the Athenian painter to be somewhat ambiguous in decorating a lekythos for export and an unknown purchaser.

A more complete domestic picture is found on a nuptial lebes, or lebes gamikos, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 13.7). The shape is a variation of the lebes or dinos used as a mixing bowl for wine and water since the sixth century; the more elaborate version seen here is associated with weddings, but its specific function in the ceremony is not certain. The vase is also used as a grave offering, but

whether it belonged to the deceased or is offered as a substitute for an unmarried woman is not certain. On the lebes, we see a well-dressed seated woman wearing a fillet (head band) and playing a harp. Behind her is a woman carrying a loutrophoros, which was used for ritual washing, either of the bride before the wedding or of a corpse before the burial. In front of her are other women carrying an array of chests; some are dressed like the seated woman and others wear just a chiton. Under each handle is a winged woman flying in toward the center picture and holding tendrils, a sash, and a box. Down below on the stand are two standing women, one holding a kalathos in her hand and the other a piece of cloth.

whether it belonged to the deceased or is offered as a substitute for an unmarried woman is not certain. On the lebes, we see a well-dressed seated woman wearing a fillet (head band) and playing a harp. Behind her is a woman carrying a loutrophoros, which was used for ritual washing, either of the bride before the wedding or of a corpse before the burial. In front of her are other women carrying an array of chests; some are dressed like the seated woman and others wear just a chiton. Under each handle is a winged woman flying in toward the center picture and holding tendrils, a sash, and a box. Down below on the stand are two standing women, one holding a kalathos in her hand and the other a piece of cloth.

The scene on the bowl may represent the epaulia, as the bride sits in her new home. Given the chair and footrest, the scene is set in an interior space. The chests would be filled with her possessions and the winged figures serve to acclaim her new status. The scene on the stand below looks ahead to the work of the matron in running the household, especially supervising the production of textiles. Whether the standing women in the main scene are family members or slaves is less clear. The shorter figure on the right is of inferior status, but the other two standing women are virtually identical except for the fillet.

According to the literary sources, these women would be in the women’s quarters of the house, the gynaikonitis. These sources suggest that there was a strict segregation of men and women in the Greek house, with women essentially being sequestered and kept respectable by avoiding going out in public or having contact with men who were not close relatives. Some of the sources also suggest that the interaction of wife and husband was limited, with men spending time in the andron and in public with other men. More recent analysis of houses and their use, however, suggests that such segregation was not rigorously enforced in the ancient Greek house and that there was fluidity and flexibility in the organization of the work of the oikos and the interaction of family members (Nevett 1999).

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1624;