middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 27 страница

cities and architecture

When Alexander died in Babylon in 323 все, there was no clear successor and his generals, called the Diadochi or “successors,” fought with each other and divided the empire amongst themselves over the next quarter-century. Ptolemy appropriated the body ofAlexander and took it to Egypt, there establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty that would last three centuries until the death of Cleopatra VII in 31. Seleukos took control of the Babylonian section of the Persian empire and by 301 had extended his control to Syria, where he founded the city of Antioch as a new capital in 300. Antipater had been viceroy in Europe and asserted control over Greece until his death in 319. Afterward his son Kassander defeated Alexander’s mother Olympias for control of Macedon. Lysimachos was given Thrace, controlling the Black Sea area and, after 301, Asia Minor, until his death in battle in 281. One general, Antigonos, was the satrap of Phrygia in Asia Minor and after Antipater’s death sought to reunify the entire Macedonian

empire, a struggle that lasted until his death in battle in 301. Alexander’s legacy was shifting Greek military and political control over a large, multicultural area from Greece to Afghanistan to Egypt.

Ptolemy initially took the body of Alexander to Memphis in Egypt, but later moved it and his capital to the new city of Alexandria, founded by the conqueror himself in 331 все. The city was laid out on a grid, with wide north-south and east-west avenues creating an X-Y axis dividing the city into quarters with a large agora at the center (Figure 14.3). The island called Pharos protected the harbor and was connected to the city by a causeway, and on it was built the lighthouse of Alexandria, at least 300 feet (91.4 m) high and one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The palace quarter (“Palast” on the plan) with its own harbor occupied the northeast section of the city, and there were numerous sanctuaries as well as a large park. The Temple of the Muses (Museion) housed the famous library of Alexandria where ancient literature was collected, studied, and edited. Estimates of the city’s population range widely, but it probably had at least a half-million residents including slaves, making it double the size of Athens, which with Syracuse/Siracusa had been the largest Greek city of the classical period. The orthogonal plan of Alexandria follows some of the principles found in new Greek cities back in the archaic period, such as Poseidonia/Paestum (see Figure 5.3, page 103), but its scale and that of Antioch were unprecedented.

ALEXANDRIA

|  |

|  |

BRUCKE

BRUCKE

14.3 Plan of early Ptolemaic Alexandria, Egypt, 3rd cent. все. After W. Hoepfner and E.-L. Schwandner, Haus und Stadt in klassischen Griechenland (Berlin/Munich, 1994), Abb. 225 (drawing by authors). Used with permission of Hans Goette and the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Berlin.

|

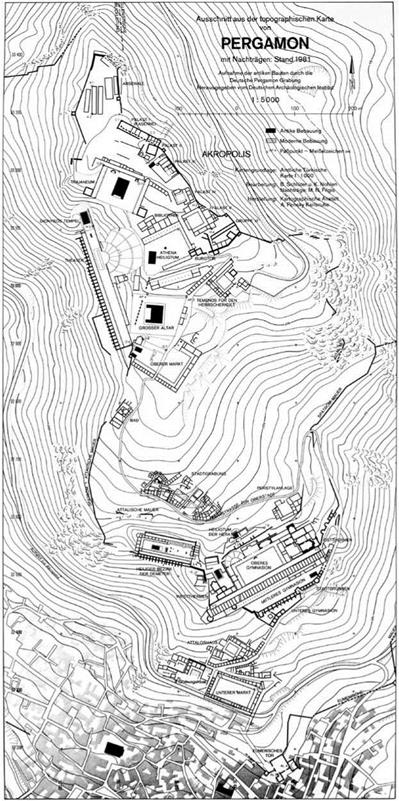

14.4 Plan of the acropolis at Pergamon, 3rd cent. все and later. After M. N. Filgis and W. Radt, Die Stadtgrabung. Teil 1: Das Heroon, AltertUmer von Pergamon XV. 1 (Berlin, 1986), Pl. 57, map by B. Schluter, K. Nohlen, and M. H. Filgis. Used with permission of Hans Goette and the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Berlin.

Orthogonal grid planning was found at other sites, including Antioch and the much smaller town of Priene in Asia Minor (see Figure 5.5, page 105). The grid here had to adapt to terrain that was more hilly than Alexandria or Antioch, but the east-west streets are able to maintain a usable grade while the north-south streets are much steeper and limited to pedestrian traffic.

Another city that rivaled Athens was Pergamon in Asia Minor. This was a small site that was built up by Philetairos, one of the generals of Lysimachos, who had entrusted Philetairos with the protection of his treasury of 9,000 talents. The steep terrain of the site was suitable for safeguarding this fortune, but following the death of Lysimachos in 281 все, Philetairos used the funds to turn Pergamon into an autonomous kingdom and to build up the city itself. He and his successors, particularly Attalos I (r. 241-197), Eumenes II (r. 197-158), and Attalos II (158-138), transformed the site into one of the most spectacular Hellenistic cities. The last Pergamene ruler, Attalos III (138-133), left the city to the Romans in his will. At the time, Pergamon was a royal city that rivaled Athens in both size and splendor, but Rome was less interested in further development of the city.

As can be seen in the plan of the city (Figure 14.4), most of the monumental buildings were concentrated in the upper acropolis, which housed the palace and barracks along the highest ridge on the east and north sides. On the west side of the acropolis, facing the valley, large terraces lined with stoas were built that housed the library (“Bibliothek”), second only to Alexandria in importance (Figure 14.5). Below these terraces, a large theater that could seat 10,000 spectators was cut into the steep bank and lined with a stoa more than 200 meters long that created a visual base for the vista. Access to the acropolis was at the southern foot of the mount (“Eumenisches Tor (Gate)”). The road led upward through a market to a middle city that featured a gymnasion and sanctuary of Demeter. From here, the road switched back and further up the mountain to reach the entrance to the upper city at a market just below the Great Altar. As can be seen in the plan and model, the main road through the acropolis twisted and turned along the summit until it reached the palace and barracks on the north.

The colonnaded terraces essentially served as stages for works like the Great Altar of Zeus (Figure 14.6). That structure, now partially reconstructed in Berlin, had a monumental frieze almost 400 feet (121.9 m) long showing the Gigantomachy (see Figure 9.4, page 215). While the altar is one of the major surviving works of Hellenistic architectural sculpture that we will discuss further below, Pergamon was filled with many sculptural groups commemorating its victories over the Gauls and others in the third century все. The lavish marble structures and terraces of the acropolis would have impressed visitors and viewers from below, long before they were able to progress though the gates at the bottom of the ridge into the city itself.

We have seen that Periklean Athens was conscious of the spectacle that its buildings created, and it is not surprising to find that the Pergamene kings also had connections to Athens as civic patrons. Several bronze groups commemorating mythological battles, called the Lesser Attalid dedication, were placed on the Acropolis, probably by Attalos I around 200 все, but possibly later by Attalos II. This second Attalos paid for the Stoa that bears his name in the Agora of Athens, which was reconstructed in the 1950s to house the Agora Museum and excavation facilities (see Figure 5.6, page 105). Indeed, the effect of the Stoa of Attalos and the adjoining south stoas was to transform the somewhat irregular space of the classical agora into a more regular and monumental form with marble stoas in the Hellenistic period. By becoming significant patrons for buildings and art in Athens, the Pergamene kings asserted a claim not just to political control of their kingdom, but as cultural leaders in the broader Greek world with their city as a cultural capital.

The staging of architecture and landscape is found at other sites, such as the Asklepieion on the island of Kos (which had purchased the clothed statue of Aphrodite by Praxiteles, while neighboring Knidos bought the nude Aphrodite). Like the Asklepieion at Epidauros, that at Kos is outside of the city. Set on a hillside at the site of a spring, the sanctuary had a cypress grove as the sacred focal point. The earliest structures were located at what is now the second terrace, with a small temple and altar, and possibly an abaton for the healing process (Figure 14.7). The cypress grove stood above this space,

14.5 Model of Pergamon: view of western side of acropolis with Great Altar of Zeus to the right. Berlin, Pergamonmuseum. Photo: Album/Art Resource, NY.

14.6

Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, c. 180-150 все, post-restoration 2004. Height of altar: 31 ft 85/16 in (9.66 m). Berlin, Pergamonmuseum. Photo: bpk, Berlin/ Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen/Johannes Jaurentius/Art Resource, NY.

Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, c. 180-150 все, post-restoration 2004. Height of altar: 31 ft 85/16 in (9.66 m). Berlin, Pergamonmuseum. Photo: bpk, Berlin/ Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen/Johannes Jaurentius/Art Resource, NY.

14.7 Asklepieion at Kos, c. 160 все. Reconstruction after P. Schazmann, Akleopieion. Baubeschreibung und Baugeschichte, Kos I (Berlin, 1932), pl. 40. Used with permission of Hans Goette and the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Berlin.

|

framed by a wooden portico. Around 175-150 все, the upper terrace was rebuilt with new marble stoas framing a large temple in front of the cypress grove; a large marble staircase created a processional axis through the space. The result of this construction was to transform the sanctuary’s organization of space to a longitudinal axis and make it more symmetric than it had been before. This offers a sharp contrast to the twisting and turning processional paths at sanctuaries like Delphi, Olympia, and the Acropolis at Athens. The new temple would have been visible over the roof of the lower terrace and propylon, making it a constant visual goal for the visitor to the sanctuary seeking the healing power of Asklepios.

Theatricism in religious architecture consists not just of framing vistas, but also of creating unexpected encounters for the visitor and enhancing the dramatic potential of the supplicant seeking healing or a prophecy. The cult of Apollo at Didyma had been famous in the archaic period for an important oracle; this had been destroyed by the Persians in 494 все and its priests sent into exile. The cult was revived by Alexander the Great and its cult image returned from Persia by Seleukos, who began construction of a new temple around 300 (Figure 14.8). At 51.1 meters wide and 109.3 meters long, it is one of the largest Ionic temples. The building has a double colonnade and its columns, 19.7 meters high, were the tallest that have ever been found in Greek architecture. Work on the building was protracted and continued through the Hellenistic period, but the building was never finished.

The temple’s base consisted of seven huge steps, elevating the platform about 4 meters above the ground. A smaller set of more normally sized steps was set on the main axis and led to a pronaos (Figure 14.9). At the monumental door between the pronaos and naos, however, the floor rises about 1.5 meters, barring entrance. Beyond the threshold was not a naos but a small room with three openings to the exterior opposite the door that is best described as an elevated porch. A second set of steps led down from this porch into the interior of the temple, which was an open courtyard housing a small temple with four columns in antis (Figure 14.10). This small structure housed the spring where the priestess gave the oracle; the interior stairs provided access to the porch for the priests, who could use the porch as a stage to make pronouncements to visitors assembled in the pronaos. Actual access to the courtyard and small temple from the pronaos was via small doorways set near the corners of the pronaos; these doors led to a barrel-vaulted sloping tunnel that went down

|  |

|

14.9 Temple of Apollo at Didyma, begun c. 300 все. Plan. After H. Berve and G. Gruben, Greek Temples, Theaters, and Shrines (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), p. 463, fig. 129. Used with permission of Hirmer Verlag.

to the ground level of the interior courtyard. At the bottom, the doors emerged into corners of the courtyard at the foot of the interior stairs. The net effect for a visitor would be to go from the light area outside the temple into a shaded but well-lit porch, and from there into a dark, narrow, descending space that emerged once more into the sunlight, but now inside the building and looking at a building within a building.

to the ground level of the interior courtyard. At the bottom, the doors emerged into corners of the courtyard at the foot of the interior stairs. The net effect for a visitor would be to go from the light area outside the temple into a shaded but well-lit porch, and from there into a dark, narrow, descending space that emerged once more into the sunlight, but now inside the building and looking at a building within a building.

Much of Hellenistic temple architecture was less theatrical and followed more closely the norms established in previous centuries. One architect, Hermogenes of Priene, who was active in the late third and early second centuries, was noted by Vitruvius for his refinements of the rules of proportions and symmetry, but only fragments of his temple at Magnesia survive. Indeed, there had always been elements of theatricism associated with religious performances and their sites, and grid planning was nothing new for city planning. What is different in Hellenistic architecture is a wider variation with the schema of Interior. Photo: Marie Greek architecture and a greater manipulation of scale and viewing points to create effective and

Mauzy/Art Resource, NY. affective vistas and experiences. Like the architectural program of Periklean Athens, large financial

resources were needed for lavish and monumental architecture. In the Hellenistic age resources were more readily available through royal and elite patrons, who were willing to expend significant funds to exercise individual or dynastic agency through the creation of impressive monuments.

sculptural styles and dating

sculptural styles and dating

The diversity of style that we saw in fourth-century sculpture becomes much more pronounced in the Hellenistic period. Given the relatively few works that can be precisely dated, this stylistic variety means that Hellenistic sculpture is difficult to discuss in terms of its chronological development. The choice of style for individual works seems more connected to its subject matter, type, function, and context, so we will explore Hellenistic sculpture more thematically than in previous chapters.

The sculpture recovered from two shipwrecks illustrates well the issues and variety of Hellenistic styles and dating. We have already seen one work, the fourth-century bronze youth recovered from the shipwreck at Antikythera, an island halfway between Crete and the southeast coast of the Peloponnesos (see Figure 12.7, page 295).

Based on its cargo, the date of the shipwreck is generally set around 80 bce, so it is probable that this statue had been taken from a site, whether by looting or other form of appropriation, and was being shipped westward, perhaps to Italy where so much fifth- and fourth- century Greek sculpture was sent following Roman conquests. There were other fourth-century bronze works in the Antikythera cargo, but there were also several marble copies of classical works, including one of the Aphrodite of Knidos (compare Figure 12.11, page 300), that were probably produced not long before being placed on the ship. By the early first century the number of classical originals to be had was undoubtedly shrinking, and workshops began producing neoclassical copies or adaptations to meet continuing demand for sculpture.

The Antikythera cargo included several marble statues that are identified as Trojan War heroes, such as the figure of Odysseus

(Figure 14.11). Trojan themes became popular for large sculptural ensembles in the first century, especially among the Romans, who traced their origins back to the Trojan prince Aeneas, who had escaped from the destruction of Troy and came with his son to Italy via Carthage. While the Odysseus statue has endured much damage from exposure to the ocean environment, one can still see that the composition is more dynamic than much of classical sculpture. Odysseus has a wide striding pose and looks back over his shoulder. The statue was likely part of a group that enacted a dramatic moment in a Trojan episode, perhaps the stealing of the Palladion, the cult statue of Athena in her temple at Troy. The figure does not move in a single direction across a flat plane, but looks in one direction while moving in another on a fully three-dimensional stage. The composition uses more diagonals in the positioning of torso and limbs, creating an asymmetry and tension in the figure that add to its drama. Sculptural ensembles are not new, and it is possible that the Riace

Warriors belonged to such a grouping, but whereas there might be some psychological tension with those figures, they are not vigorously acting out a dramatic moment in the way that the Antikythera figures would as part of an ensemble.

While the stylistic details of the statue are hard to read because of the erosion and damage, it resembles works in the so-called baroque style of Hellenistic art. The term, deriving from the name used to describe seventeenth-century European art and artists like Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt, emphasizes the strong contrast of light and dark, the use of diagonals, and dramatic poses and expressions, and is applied to works like the Pergamon altar (see Figure 9.4, page 215). The term, like Daedalic for seventh- century sculpture, is problematic but appears frequently in the literature and does have a descriptive value. Dating the Antikythera Odysseus on the basis of style, however, is difficult because it, like the contemporary classical-style copies on the same ship, was being produced by workshops for clients across the Mediterranean, and perhaps even by the same workshop. Essentially, a theatrical or baroque style was used for a dramatic narrative, while a neoclassical style was used for a replica of Aphrodite that was likely seen on its own, not as part of an ensemble.

While the stylistic details of the statue are hard to read because of the erosion and damage, it resembles works in the so-called baroque style of Hellenistic art. The term, deriving from the name used to describe seventeenth-century European art and artists like Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt, emphasizes the strong contrast of light and dark, the use of diagonals, and dramatic poses and expressions, and is applied to works like the Pergamon altar (see Figure 9.4, page 215). The term, like Daedalic for seventh- century sculpture, is problematic but appears frequently in the literature and does have a descriptive value. Dating the Antikythera Odysseus on the basis of style, however, is difficult because it, like the contemporary classical-style copies on the same ship, was being produced by workshops for clients across the Mediterranean, and perhaps even by the same workshop. Essentially, a theatrical or baroque style was used for a dramatic narrative, while a neoclassical style was used for a replica of Aphrodite that was likely seen on its own, not as part of an ensemble.

A second shipwreck at Mahdia, on the coast of Tunisia, probably dates to a decade or two after the Antikythera shipwreck, about 70-60 bce. Its cargo was also quite varied, and included large marble kraters (compare Figure 11.11, page 280) and architectural elements, including capitals with chimera motifs and Ionic columns made in Athens.

There were also classicizing marble statues, an archaistic bronze herm of Dionysos, and several bronze statues. One of these, an Eros (once identified as “Agon” or the personification of athletic competition), is a classicizing statue (Figure 14.12). It bears some similarities to the work of Polykleitos or some of the youths on the Parthenon frieze (compare Figure 1.1, page 2), but there is an exaggeration in the curve of the limbs and torso and a softer quality to the musculature that suggest a Hellenistic date.

In the same cargo was a series of small dancing dwarves that are in a more dramatic style, with extended limbs and strong diagonal composition that would have been completely unstable in stone (Figure 14.13). The facial expression is more animated than the Eros and while the musculature does not bulge like that of the giants of the Pergamon altar or the Antikythera Odysseus, the multiple directions of movement and gaze have a similar three-dimensionality. The widespread interest in a non-ideal type of figure, a dwarf that by definition does not meet the idealized canon of proportions of the Doryphoros, is new in sculpture during the Hellenistic period, although not in other media like vase painting. The combination of subject matter and dance movement is often labeled rococo to distinguish a lighter type of theatrical style than the baroque. Rococo sculpture has many elements of the baroque, such as strong movement and diagonals, but the subject matter is lighter, more humorous, or erotic. Analysis of the bronze core of one of the dwarves, no. F215, shows that its materials are very similar to the Eros statue, suggesting that both the classicizing and rococo bronzes of the Mahdia cargo might have been made in the same workshop. Their differences in style, scale,

In the same cargo was a series of small dancing dwarves that are in a more dramatic style, with extended limbs and strong diagonal composition that would have been completely unstable in stone (Figure 14.13). The facial expression is more animated than the Eros and while the musculature does not bulge like that of the giants of the Pergamon altar or the Antikythera Odysseus, the multiple directions of movement and gaze have a similar three-dimensionality. The widespread interest in a non-ideal type of figure, a dwarf that by definition does not meet the idealized canon of proportions of the Doryphoros, is new in sculpture during the Hellenistic period, although not in other media like vase painting. The combination of subject matter and dance movement is often labeled rococo to distinguish a lighter type of theatrical style than the baroque. Rococo sculpture has many elements of the baroque, such as strong movement and diagonals, but the subject matter is lighter, more humorous, or erotic. Analysis of the bronze core of one of the dwarves, no. F215, shows that its materials are very similar to the Eros statue, suggesting that both the classicizing and rococo bronzes of the Mahdia cargo might have been made in the same workshop. Their differences in style, scale,

and composition suggest that a workshop was not limited to a single style in its production at this time.

Whether the bronzes were made at the same time as the architectural elements, which had likely been commissioned for a specific building project and must date to around the time of the shipwreck, or were somewhat older “antiques” dating around 100 bce, is unclear, but certainly clients had eclectic interests in subject matter and styles that workshops and dealers supplied.

Whether the bronzes were made at the same time as the architectural elements, which had likely been commissioned for a specific building project and must date to around the time of the shipwreck, or were somewhat older “antiques” dating around 100 bce, is unclear, but certainly clients had eclectic interests in subject matter and styles that workshops and dealers supplied.

The Antikythera and Mahdia shipwrecks speak to a change in the production and consumption of sculpture in the Hellenistic period. Whereas raw materials and nearly finished sculpture had been transported long distances in the archaic and classical periods, the extent to which both materials and sculptors moved about in the Hellenistic period was larger. Athens remained an important center of production, particularly for works in a classicizing style, and much of its production was shipped to Roman clients in the Mediterranean. In light of this, the date of other works found at sea, like the Riace Bronzes (see Figure 10.5, page 241), is open to question. As discussed in the textbox for this chapter, it is possible that the Riace Bronzes are not fifth-century originals but first-century works made for the Hellenistic market.

Indeed, the Roman empire became a crucial factor in Hellenistic art, in part through political events and in part through patronage. During the late third century, the Roman sacking of Syracuse/Siracusa, one

of the greatest classical Greek cities in size and artistic importance, and two years later of Taras/ Taranto saw large quantities of Greek art taken to Rome and to the villas and houses of its leaders as trophies and booty. Indeed, Rome became flooded with Greek art, a trend that continued as Rome turned its attention to the Greek mainland in the second century. The sack of Corinth in 146 brought yet more works to Rome, and the Roman taste for Greek work provided a steady demand that was met by the production of new works in classicizing and other styles, as the Antikythera and Mahdia shipwrecks demonstrate.

of the greatest classical Greek cities in size and artistic importance, and two years later of Taras/ Taranto saw large quantities of Greek art taken to Rome and to the villas and houses of its leaders as trophies and booty. Indeed, Rome became flooded with Greek art, a trend that continued as Rome turned its attention to the Greek mainland in the second century. The sack of Corinth in 146 brought yet more works to Rome, and the Roman taste for Greek work provided a steady demand that was met by the production of new works in classicizing and other styles, as the Antikythera and Mahdia shipwrecks demonstrate.

In approaching Hellenistic sculpture, then, we shall consider format and subject matter more than chronology and stylistic development as we have done in other chapters. We will begin with the more dramatic styles typically used in narrative sculpture, to which the term baroque has often been applied. A more private and light-hearted version of the style, often called rococo, should also be viewed as part of a theatrical mode of sculpture like the baroque. Whereas commemorative sculpture in the form of grave monuments and votive statues is not unusual, there is a new effort to represent a more lifelike and realistic version of individuals that becomes, at least on a royal level, true portraiture in the Hellenistic period in a style that is often labeled realistic. The sacred continues to be an important subject for sculpture and cult statues continue to be made, but there are several different styles associated with this context, including a neoclassical (or classicizing), neo-severe (severizing) style, and neo-archaic (archaizing) style, as well as more theatrical compositions.

theatricism and narrative

We noted earlier the prominent placement of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, and the sculptural program from the building is one of the most significant of the Hellenistic period, both as an example of the baroque style and for providing grounds for dating (see Figure 14.6). A fragmentary inscription, BASILISS(A) or queen, refers to Apollonis as queen mother and therefore links the structure to one of her sons, Eumenes II (r. 197-158 все) or Attalos II (158-138). Whether work began after the Battle of Apamea in 188, which confirmed Attalid rule over Pergamon, or after the wars with the Gauls in 168-166, is less certain, although the subject of the exterior frieze, a Gigantomachy, is likely meant to symbolize an important victory. An interior frieze lining the court at the top of the steps shows the life of Telephos, son of Herakles and the mythological ancestor of the dynasty. The central section of the monument was not finished, suggesting a terminus ante quem of 133, when the last Pergamene king, Attalos III, transferred the kingdom to Roman rule on his death. Work likely took a couple of decades for completion, and the signatures of at least fifteen sculptors survive from the Gigantomachy frieze, confirming that a large workshop was organized for the project. Taking all of this into account, a date of 180-150 все is usually assigned to the altar and it is considered to be a victory monument in a manner analogous to the Parthenon three centuries earlier.

As noted in Chapter 9 (see page 214), the Gigantomachy frieze is monumental in scale and wraps completely around the altar. It is first approached from its back and leads the viewer around the side and up the steps at the front (see Figure 9.4, page 215; Figure 14.5). The nude giants have dramatically diagonal poses, with limbs and bodies frequently moving in different directions. The musculature is exaggerated in size and bulging; deep drilling and undercutting create a strong contrast between light and dark. The faces are rendered with worry lines, recessed eyes, and open mouths that capture the pathos of attacked figures. The faces of the gods are smoother and more serene yet still focused, but the undercutting of their drapery and their lunging poses give them decisive movement and action. These are figures that do not seem frozen in a pose, but stopped in an instant of motion, and this quality distinguishes the baroque style.

There is certainly an element of theatricism and viewer engagement with the Pergamon altar. Whereas architectural sculpture is often at some distance above a viewer and, outside of pediments, usually smaller than life-size in scale, the Gigantomachy frieze is 2.3 meters high, making its figures even larger than heroic-scale statues like the Doryphoros. Sitting only about 3 meters above the ground and carved in very deep, three-quarter relief, these figures, especially the giants, seem as if they are about to spill out into the viewer’s immediate space, and indeed share the space as the steps mount toward the entrance above (see Figure 9.4, page 215).

The baroque or theatrical style seems particularly well suited to narrative subjects, as we see in the poses of the Trojan War figures from the Antikythera shipwreck (see Figure 14.11) and also in the figures from the grotto at Sperlonga that we saw in Chapter 11 (see page 281 and Figures 11.14 and 11.15, page 283). These five sculptural groups were made by three Hellenistic sculptors from the island of Rhodes, Hagesandros, Athenodoros, and Polydoros. The style of the sculptures is very similar to the Pergamon altar, and this has led to controversy over dating the Sperlonga ensemble, which was clearly made for the specific site. Were these three artists second-century artists in Rhodes whose work was copied in the first century for the grotto, or were they Greek artists working in the middle of the first century for Roman clients, probably the imperial family, using a style like that of the Pergamon altar? On the whole, the latter alternative seems more plausible, but the debate shows that the theatrical style had a lasting appeal throughout the Hellenistic period.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1133;