middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 16 страница

choice of mood and moment

With this last example, we can also consider the genre or mood of a visual narrative. Comic narrative is clearly intended to amuse, and can take various forms such as satire and parody, visual puns, exaggeration, and slapstick. Most of the narratives we have seen are more serious and straightforward. Pictorial narrative can also emulate some of the features of dramatic tragedies, involving sudden changes of situation and a focus on the choices of the characters rather than strenuous action, such as the scene at the tomb of Agamemnon in Figure 9.11. We might also include more universalizing scenes such as the departure of a warrior, warriors fighting, or a marriage scene as a genre of narrative as well.

Judging from the plays and other testimony, comedy was very popular both as a theatrical medium and in poetry. Identifying humor in art is difficult, in that comic devices such as puns are harder for us to recognize or understand today. The dress of comic actors (see Figure 12.21, page 310) provides a cue to us that there is a comic rather than serious narrative intent, but we should consider that comedy could be created by pictures through the demeanor of the figures and the choice of moment shown.

One way to identify a comic narrative would be through its contrast to more standard representations of a scene. For example, we saw earlier Kirke transforming the sailors of Odysseus as the hero charges toward her in a straightforward synoptic narrative (see Figure 9.6). There is a trace of irony, given the context of the symposion, since Kirke’s cup doubles for the actual cup in the hands of the drinker/viewer, but the scene itself is not particularly comic in its action. Another representation of the scene, on a late fifth-century, black-figure skyphos from Boeotia, is quite different (Figure 9.12). The deep cup is one of many examples that are connected to the sanctuary at Cabiros, called Cabiran Ware, that feature a much more caricature-like style than contemporary red-figure pottery from Athens. On the right is a loom, a symbol of domesticity that we saw in the Penelope skyphos (see Figure 5.19, page 118), but in the case of Kirke it is somewhat deceptive given her powers. She holds out a skyphos and wand toward Odysseus on the left. Both faces have exaggerated eyes, noses, and mouths like the masks of the actors on the Paestan krater, and Odysseus has a fake enlarged phallus as well. As in other representations of the story, Odysseus has charged in with a drawn sword, but now he is stopped in his tracks and stumbles backwards, defying the expectations of the viewer. Rather than being in control of the

| |||

| |||

situation, Odysseus is rebuffed by an unarmed woman. We are not entirely sure about the nature of the Cabiran mysteries, but it is possible that they involved humor and satire that ridiculed heroes or gods.

Satyrs are good for humorous antics as well (see Figure 11.8, page 277), and can be effective for satire by mocking the behavior of heroes and gods. A red-figure chous, a special pitcher used in the Anthesteria festival of Dionysos that celebrated the new year’s new wine, shows a satyr with a club and cloak attacking a snake in a tree (Figure 9.13). Rather than fruit, the tree bears pitchers like the chous itself. The scene is a parody of Herakles getting the apples of the Hesperides from a tree guarded by a dragon, one of his twelve canonical labors (Walsh 2009, 238). The satyr’s club is an attribute of Herakles, so the satyr is substituting for the hero, but attacking a curious snake rather than a hostile monster. Instead of apples, the satyr desires the wine of the chous pitchers in the tree and is willing to endure this “heroic” trial for his prize. His pose is heroic and muscular, but his satyr head hardly fits with the heroic body, and the prize is not the means to immortality that are the apples.

For a tragic narrative mood, we might look for pictures that concentrate on a moment of decision. For example, we saw that Exekias’s version of the suicide of Ajax (see Figure 9.5) was quite different from much archaic narrative, in that Exekias represented the moment of decision to take action by planting the sword, rather than the more climactic result of lying on the sword that is more typical of representations of the story. Although Exekias worked before the time when drama first developed, attributed to Thespis in the later sixth century, Exekias’s composition could be called tragic in mood by focusing on choice and character rather than climactic action.

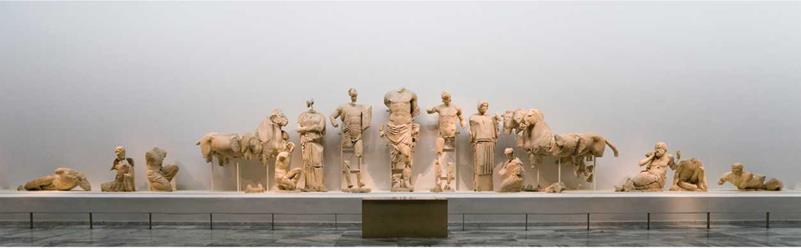

We see a similar approach to the story of Pelops and Oinomaos on the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, dated to 470-457 все (Figure 9.14). This is not a common subject for Greek narrative art, but it is appropriate for the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The basic story is that there was a prophecy that Oinomaos, king of nearby Pisa, would be killed by his son-in-law. He tried to prevent this by challenging all suitors to a chariot race in which he would give a head start to the suitor, but would kill him if he caught up. Since he had horses provided by Ares, this gave him an advantage and so far a number of suitors had died. Pelops was successful, and in the race Oinomaos

lost his life, leaving the kingdom to Pelops (who also gave his name to the southern peninsula of Greece, the Peloponnesos). Since the city of Elis had defeated Pisa for control of the sanctuary in 470 and began the temple immediately afterward, featuring the race that the king of Pisa had lost would be an appropriate subject symbolizing the victory of Elis.

Our literary sources have different reasons as to why Pelops won. In Pindar’s account (Olympian 1), our earliest version dating to 476 все and hence before the temple was started, Pelops was given horses by Poseidon, a former lover; with these he was successful in neutralizing the unfair advantage of Oinomaos. A slightly later version, c. 440, by the Athenian mythog- rapher Pherekydes, states that Pelops bribed Myrtilos, charioteer of Oinomaos, to sabotage the wheel of Oinomaos’s chariot, causing it to fall off during the race and precipitate the king’s death. Pelops later killed Myrtilos when he tried to collect the bribe, and the charioteer called a curse down on the family. Certainly the family of Pelops was cursed. Atreus, the oldest son and Pelops’s successor, killed the children of his brother Thyestes, serving them to their father in a stew, apparently because Thyestes plotted to overthrow Atreus by sleeping with his wife. Thyestes was exiled along with his remaining son, Aigisthos. The curse continued into the next generation when Agamemnon, the son of Atreus, sacrificed his daughter Iphigeneia to sail to Troy. While he was away, his wife Klytaimnestra slept with Aigisthos and together they plotted to murder Agamemnon on his return. Finally, the son of Agamemnon, Orestes, acting on the word of Apollo, killed his uncle and mother but was set upon by the Furies, who were finally appeased by the intervention of Athena. The story of the house of Agamemnon is the subject of a trilogy composed by Aeschylus in 458 все that serves as a foundational story for trial by jury in the polis. With such a legacy, the oath of Pelops and Oinomaos at Olympia and its interpretation become entangled in the competing versions of the oath and its aftermath.

Our literary sources have different reasons as to why Pelops won. In Pindar’s account (Olympian 1), our earliest version dating to 476 все and hence before the temple was started, Pelops was given horses by Poseidon, a former lover; with these he was successful in neutralizing the unfair advantage of Oinomaos. A slightly later version, c. 440, by the Athenian mythog- rapher Pherekydes, states that Pelops bribed Myrtilos, charioteer of Oinomaos, to sabotage the wheel of Oinomaos’s chariot, causing it to fall off during the race and precipitate the king’s death. Pelops later killed Myrtilos when he tried to collect the bribe, and the charioteer called a curse down on the family. Certainly the family of Pelops was cursed. Atreus, the oldest son and Pelops’s successor, killed the children of his brother Thyestes, serving them to their father in a stew, apparently because Thyestes plotted to overthrow Atreus by sleeping with his wife. Thyestes was exiled along with his remaining son, Aigisthos. The curse continued into the next generation when Agamemnon, the son of Atreus, sacrificed his daughter Iphigeneia to sail to Troy. While he was away, his wife Klytaimnestra slept with Aigisthos and together they plotted to murder Agamemnon on his return. Finally, the son of Agamemnon, Orestes, acting on the word of Apollo, killed his uncle and mother but was set upon by the Furies, who were finally appeased by the intervention of Athena. The story of the house of Agamemnon is the subject of a trilogy composed by Aeschylus in 458 все that serves as a foundational story for trial by jury in the polis. With such a legacy, the oath of Pelops and Oinomaos at Olympia and its interpretation become entangled in the competing versions of the oath and its aftermath.

The sculpture at Olympia was found dispersed across the site during the excavations there, and controversies persist to this day regarding the placement of the figures and determining the narrative direction. The identity of the five main figures seems well established, and we will discuss the composition as it appears in the current installation in the museum at Olympia. In the center stands Zeus, at a larger scale than the mortals around him. Before him, on our left, king Oinomaos of Pisa sets out the terms of a race, while Pelops listens to our right. Oinomaos is bearded whereas Pelops is not, and so is designated the senior figure. Flanking Oinomaos is his wife Sterope, mother of Hippodamia, who stands next to Pelops and pulls at her mantle in a gesture associated with the anakalypsis, the revealing of the bride in marriage. On either side of the central group are the chariot teams being readied by the attendants for the race. Beyond them are two seated figures who are seers; the one on the right, called the Old Seer, holds his hand to his face and has opened his mouth in what is seen as a gesture of concern. Personifications of the river gods lie at the corners of the pediment.

The sculpture at Olympia was found dispersed across the site during the excavations there, and controversies persist to this day regarding the placement of the figures and determining the narrative direction. The identity of the five main figures seems well established, and we will discuss the composition as it appears in the current installation in the museum at Olympia. In the center stands Zeus, at a larger scale than the mortals around him. Before him, on our left, king Oinomaos of Pisa sets out the terms of a race, while Pelops listens to our right. Oinomaos is bearded whereas Pelops is not, and so is designated the senior figure. Flanking Oinomaos is his wife Sterope, mother of Hippodamia, who stands next to Pelops and pulls at her mantle in a gesture associated with the anakalypsis, the revealing of the bride in marriage. On either side of the central group are the chariot teams being readied by the attendants for the race. Beyond them are two seated figures who are seers; the one on the right, called the Old Seer, holds his hand to his face and has opened his mouth in what is seen as a gesture of concern. Personifications of the river gods lie at the corners of the pediment.

Looking at the pediment, the emphasis is not upon the race but upon the oath taken by the participants beforehand setting out the terms. Oinomaos’s pose is strident and has been seen as

|

9.14 East pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, c. 470-457 все. Height of central figure: 10 ft 2 in (3.1 m). Olympia Museum. Oath of Pelops and Oinomaos. Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

arrogant, particularly as he is attempting to defy a divine prophecy and is also denying the opportunity for an heir to the kingdom by preventing the marriage of his daughter. Whether Pelops is competing fairly or not is hard to say based on what we see. The Old Seer is certainly expressing concern at what he sees. A viewer could read this as shock at Oinomaos, who will die, Pelops, who may be cheating, or at both for violating or intending to violate their oath. Whatever the case, it is the oath that is the important action of the narrative. Zeus, as arbiter of oaths, becomes central in overseeing the consequences of the action.

The ritualistic context of the temple also helps to explain why the oath would be an appropriate narrative, in that the open area in front of the temple is where the Olympic athletes swore their competition oaths (see Figure 7.3, page 158). In either version of the story, Oinomaos has been cheating by having divine horses, and his eventual demise is the consequence of his false oath. Given that the Temple of Zeus was built by the Eleans, who had defeated the nearby Pisans for control of the sanctuary, this makes Pelops’s triumph over Oinomaos a metaphor for the Eleans’ victory over the Pisans. As Judith Barringer has pointed out, it is not likely that the Eleans would suggest that Pelops, too, cheated, as he was worshipped at the site (Barringer 2008, 51-52).

The ritualistic context of the temple also helps to explain why the oath would be an appropriate narrative, in that the open area in front of the temple is where the Olympic athletes swore their competition oaths (see Figure 7.3, page 158). In either version of the story, Oinomaos has been cheating by having divine horses, and his eventual demise is the consequence of his false oath. Given that the Temple of Zeus was built by the Eleans, who had defeated the nearby Pisans for control of the sanctuary, this makes Pelops’s triumph over Oinomaos a metaphor for the Eleans’ victory over the Pisans. As Judith Barringer has pointed out, it is not likely that the Eleans would suggest that Pelops, too, cheated, as he was worshipped at the site (Barringer 2008, 51-52).

However, by focusing on the moment of decision rather than the consequent action, it is possible for a viewer to regard Pelops in the same light as Oinomaos and give a very different direction to the story, one that encompasses the many murders that plague the house of Pelops. Ultimately, the viewer has to fill in the gaps of the narrative to develop a reading of the story, whatever the original intentions of the designers may have been.

symbolic and universal aspects of narrative

In looking at Greek narrative, we have to think not only about the immediate story and viewing circumstances, but also about the symbolic value of narrative for contemporary culture and events. Whereas there were many decisive events in Greek history, such as the battles of the Persians and Greeks, Athenians and Spartans, the sack of Athens in 480 все, and others, rarely did Greek artists show these events as narrative pictures. Rather, battles such as those of the Lapiths and Centaurs, the Greeks and Amazons, the Trojan War, and the Gigantomachy served sometimes as metaphors for historical events. To end this chapter, we will explore some of the symbolic value of Greek narrative art and consider its appeal to a non-Greek audience like the Etruscans.

An Attic black-figure amphora with a scene of the apotheosis of Herakles was discovered in Poseidonia/Paestum just north of the agora (Figure 9.15). It and eight bronze vases were excavated in a roofed, rectangular chamber that was dug into the ground within a temenos (see Figure 5.3, page 103). Inside the vases had been placed around a stone platform with remains of

9.16 Attic black-figure column krater, mid-6th cent. bce. From the Tomb of the Panathenaic Amphorae, Orvieto. Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 22203. Warriors fighting.

Photo courtesy Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence.

Photo courtesy Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence.

iron, cloth, and lead, possibly the remains of a bed or couch. There is no inscription to identify the chamber or its dedication, but it is thought to be a heroon, built as a tomb but without a body, perhaps in honor of a founder of Poseidonia/Paestum or its mother city, Sybaris. Some of the bronze vessels contained offerings of honey sealed with wax, but the subject of the single figured amphora is symbolically interesting. As a reward for his assistance to the gods and for his heroic deeds, Herakles was granted immortality and married to the goddess Hebe. In the sixth century scenes of the apotheosis, or deification, of Herakles became common in Athenian art, following a formula of Athena driving him in a chariot. This subject becomes particularly meaningful within the context of the Poseidonia/Paestum heroon, since its dedicatee was honored by the citizens of the town as a deified hero, who lives on through their veneration and memory, as does Herakles. It is not always possible to hypothesize a symbolic connection between a narrative and context, but it is important to remember that narrative could function as a metaphor, relying upon its symbolic value to link the present with the past.

Another vase, an Attic black-figure column krater, was found in an Etruscan tomb in Orvieto, the Tomb of the Panathenaic Amphorae (Figure 9.16). On one side of the vase is a scene of a warrior departing, a theme we will examine below. The other is a universal scene of two warriors fighting over a fallen warrior who lies at their feet. There are a few dots in front of the warriors’ helmets that look a bit like inscriptions, but these are anonymous warriors like those on the Middle Geometric skyphos from Eleusis (see Figure 9.2, page 213). Clearly the artist could have

provided an attribute or inscription if necessary, but we can consider what value it might have to leave the subject ambiguous. The vase was exported from Athens around the middle of the sixth century, about two decades after the Francois Vase (see Figure 8.23, page 203) when foreign markets, especially in Etruria, had become an important outlet for Attic painted pottery. Orvieto was a common destination for such pottery, but it is well inland from the coast, making transportation of such a large vessel to its destination an added effort and expense.

As we have noted in Chapter 8, Attic pottery did distinguish itself by representing a very large number of narrative scenes that were otherwise unavailable in competing wares. Mythological pictures would have had an appeal, particularly for Etruscans who had some familiarity with Greek mythology, but the images could have had a broader attraction.

As we have noted in Chapter 8, Attic pottery did distinguish itself by representing a very large number of narrative scenes that were otherwise unavailable in competing wares. Mythological pictures would have had an appeal, particularly for Etruscans who had some familiarity with Greek mythology, but the images could have had a broader attraction.

Even if a scene like the warriors fighting on this krater was not transformed into a mythological scene like Achilles and Memnon by the addition of inscriptions, as on the Siphnian Treasury, the action itself would have had value for the deceased and the family. Just as in Greek cities, members of a household would leave for war and fight in battle. Actual

battles did not feature the duels represented in most battle scenes like this. The focus on elite warriors fighting conferred a heroic scale on the anonymous figures for the viewer. As if to reinforce this, the warriors are watched by a variety of spectators: adult men, youths, and women, the members of the city who would witness and remember the deeds of a city’s soldiers. Vases such as this might have been used in a household as part of the Etruscan equivalent of the symposion and then placed into the tomb in honor of the deceased. In either case, the narrative picture mirrors on a heroic scale the actions of its users and culture, a symbolic value that would appeal to both Greek and non-Greek viewers according to their situation.

Many of the action scenes in Greek pottery are not specific subjects, like the deeds of Herakles, but are formulaic and can represent the action of an individual within a more universal setting. For example, the third-century metope from a tomb in Taras/Taranto shows a warrior on horseback attacking a fallen soldier (Figure 9.17). The rider is shown in armor and gear like a real cavalryman, but the opponent is nude except for his shield. This is a formulaic battle composition that was common in art from the sixth century onward and can also be seen in another work, the cenotaph of Dexileos from 394/3 все (see Figures 12.12 and 12.13, pages 301, 302). The metope in Taras/Taranto is one of six combats on the tomb, but none shows details that would link them to a specific individual or battle. Indeed, the inscription for Dexileos’s monument tells us that he died fighting, so the triumphant rider in battle is not a true-to-life representation of Dexileos in battle either. Rather, the triumphant rider composition creates a heroic narrative for the deceased that becomes, like a kouros or kore figure, an idealization of the individual. We might call narrative representations such as this universalizing, in that rather than showing specific contemporary events, a heroic formula symbolizes the achievements of the deceased.

Indeed, many if not most of Greek narrative pictures are similarly universal. The body of a red- figure krater of the middle of the fifth century shows a young man in armor and cloak and holding a spear, reaching out to touch the hand of a woman who holds a second spear and helmet (Figure 9.18).

|

Between them is another woman holding a phiale and oinochoe to pour a libation. Other women and an old man seated at the far left look on, while an adult man wearing a wreath walks away. The scene shows the warrior’s departure from his home to fight in the army. The women might include a wife, mother, sister or other relations, while the old man could be his father, or grandfather if the departing man is the head of the household. The ages and relationships of the figures are ambiguous, but this is part of the appeal of the narrative composition for the viewer. In purchasing such a vase, whether to use in a symposion or to put into a tomb as a grave good, the owner can identify these idealized figures according to his or her particular circumstances. Most men who owned such a vase as this would have fought in the army and participated in a departure ceremony, although not as rich or elaborate as this one, as would most of the women in a family. Making a pot like this for export, the painter uses narrative scenes that can become specific through the actions of the viewer/owner of the vase.

|

Turning back to the battle scene on the Middle Geometric skyphos from Eleusis (see Figure 9.2, page 213), itself a grave good, we can understand even these simple action pictures of the Geometric period in the same way, as idealized and universal narratives that show the story of actual lives in a heroic, timeless way. In looking at hunting scenes (see Figure 6.11, page 141) or wedding scenes (see Figure 13.4, page 326), we should consider how the narrative represents the ethos or character of its participants, and, by extension, the ethos of the viewers or recipients of the work. Context, then, shapes the results or “readings” of the narrative, even to the present day.

references

Aeschylus, Choephoroi. 1953. In Oresteia: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides, tr. R. Lattimore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barringer, J. M. 2008. Art, Myth, and Ritual in Classical Greece. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Connelly, J. B. 1996. “Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze.” American Journal of Archaeology 100, 58-80.

Connelly, J. B. 2014. The Parthenon Enigma. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Davies, M. 1986. “A Convention of Metamorphosis in Greek Art.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 106, 182-183.

Homer, Iliad. 1951. The Iliad of Homer, tr. R. Lattimore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurwit, J. M. 1982. “Palm Trees and the Pathetic Fallacy in Archaic Greek Poetry and Art.” Classical Journal 77, 193-199.

Hurwit, J. M. 1983. “Professor Hurwit Replies.” Classical Journal 78, 200-201.

Madden, J. D. 1983. “The Palms Do Not Weep: A Reply to Professor Hurwit and a Note on the Death of Priam in Greek Art.” Classical Journal 78, 193-199.

Osborne, R. 1988. “Death Revisited, Death Revised: The Death of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece.” Art History 11, 1-16.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. D. 2011. Looking at Greek Art. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Steiner, A. 2007. Reading Greek Vases. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stewart, A. 1983. “Stesichoros and the Francois Vase.” In W. Moon, ed. Ancient Greek Art and Iconography, 53-74. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Taplin, O. 2007. Pots and Plays: Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase-Painting of the Fourth Century B.c. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Walsh, D. 2009. Distorted Ideals in Greek Vase-Painting: The World of Mythological Burlesque. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

further reading

Carpenter, T. H. 1991. Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. London: Thames and Hudson.

Giuliani, L. 2013. Image and Myth: A History of Pictorial Narration in Greek Art, tr. J. O’Donnell. Chicago/ London: University of Chicago Press.

Junker, K. 2012. Interpreting the Images of Greek Myths, tr. A. Kunzl-Snodgrass and A. Snodgrass. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, A. G. 2009. Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shapiro, H. A. 1994. Myth into Art: Poet and Painter in Classical Greece. London: Routledge.

Small, J. P. 2003. The Parallel Worlds of Classical Art and Text. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snodgrass, A. 1982. Narration and Allusion in Archaic Greek Art. Eleventh J. L. Myres Memorial Lecture. Oxford: Leopard’s Head Press.

Squire, M. 2009. Image and Text in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. D. 1999. Pictorial Narrative in Ancient Greek Art. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Steiner, A. 2007. Reading Greek Vases. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Taplin, O. 2007. Pots and Plays: Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase-Painting of the Fourth Century B.c. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

the fifth century

(C 480-400 bce)

Timeline

Architecture, Architectural Sculpture, and Relief The Acropolis at Athens Late Fifth-Century Sculpture Painting

Textbox: The Parthenon Marbles and Cultural Patrimony

References Further Reading

A History of Greek Art, First Edition. Mark D. Stansbury-O’Donnell.

© 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

timeline

| Architecture | Sculpture | Painting | Events | |

| 480-450 | Temple of Aphaia at Aigina, after 480 Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470-457 | Kritios Boy, c. 480 Tyrannicides, 477/6 [5.9]* Artemision God, 460 [1.7] | Attic RF hydria by Kleophrades Painter, 480 Tomb of the Diver, 470 Attic RF krater by the Niobid Painter, 460 Sotades Painter Cup, 460-450 | 480 Sack of Athens, Battle of Salamis 479 Battle of Plataia 462-451 Athens fighting Sparta 454 Removal of Delian Treasury to Athens 450 Peace treaty with Persia |

| 450-430 | Parthenon, 447-432* Propylaia, 437-432 | Doryphoros, 450-440 Parthenon metopes, 447-442* Parthenon frieze, 442-438* Parthenon pediments, 437-432* | Attic WG lekythos by Achilles Painter, 440 | Perikles as leader of Athens; peace with Persia and Sparta |

| 430-400 | Erechtheion, 431-404 Nike Temple, 430-420 | Nike of Paionios, 420 Nike Temple parapet, 420-410 | Attic RF epinetron by Eretria Painter,425-420 Attic WG lekythos by Reed Painter, 420-400 | 431-404 Peloponnesian War 429 Death of Perikles |

| 'Works for which an absolute chronological date can be suggested. |

As we saw in Chapter 8, the archaic kouros and kore statues became considerably more naturalistic in their appearance by the early fifth century. Whereas the torso of the kouros of Pytheas and Aeschrion is modeled to make it look more lifelike (see Figure 8.11, page 192), the pose is still symmetrical (with the exception of the slightly advanced left leg), the structure of the face is still spherical, the eyes protrude from the skull, and he still bears the archaic smile. While not truly a smile in the sense of being an expression of joy or pleasure, it makes the face mask-like and prevents the viewer from reading the facial expression for signs of the figure’s emotions or thoughts. Around 480 все, we can see a changing conception of the human figure in art, one that mimics in stone, bronze, or painting both the physical movement and the emotional expression of the human body. Aeschylus uses the term mimesis in one of his satyr plays to describe the image of a satyr that is being presented as a votive offering by a “real” satyr: “This imitation [mimema] of Daidalos lacks only a voice ... It would challenge my own mother! For seeing it she would clearly turn and [wail] thinking it to be me, whom she raised. So similar is it [to me]” (tr. Morris 1992, 218). The idea behind mimesis is that the image both resembles the object it is imitating and can evoke a response in the viewer akin to seeing the real thing (Stansbury-O’Donnell 1999, 111-114). Thus the experience and engagement of the viewer are transformed in fifth-century art, along with the appearance of the human figure.

We can see an early example of the more naturalistic treatment of the movements of the human figure in a half life-size statue from the Acropolis called the “Kritios Boy” (Figure 10.1). The statue is named after the sculptor Kritios, who along with Nesiotes made the bronze originals of the Tyrannicides in 477/6 все that has some stylistic similarities to the youth, even in the Roman copies preserved today (see Figure 5.9, page 108). The doughy quality of the cheeks and flesh, in particular, has led to the term Severe Style being applied to the works of the early classical period, c. 480-450.

We can see an early example of the more naturalistic treatment of the movements of the human figure in a half life-size statue from the Acropolis called the “Kritios Boy” (Figure 10.1). The statue is named after the sculptor Kritios, who along with Nesiotes made the bronze originals of the Tyrannicides in 477/6 все that has some stylistic similarities to the youth, even in the Roman copies preserved today (see Figure 5.9, page 108). The doughy quality of the cheeks and flesh, in particular, has led to the term Severe Style being applied to the works of the early classical period, c. 480-450.

The most striking difference in the Kritios Boy from the kouros is the pose. Instead of the left leg being advanced, the left leg here is positioned directly under the torso while the right leg is forward and is bent at the knee rather than straight like a kouros. In a human body this would mean that most of the weight of the body would be on the straight left leg, rather than evenly distributed on two feet. The pose is typical of the way that humans stand and move around, unlike the stiffer posture of the kouros. While this shifting of the weight to one limb seems straightforward, anyone who has watched an infant learn to stand and then to walk realizes how complex are the adjustments in the human body to maintain balance. To represent the dynamic balance of a standing figure, the sculptor has had to make many small adjustments in the composition of the body.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1114;