middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 18 страница

The columns are also not perfectly vertical but lean inward about 2 inches (5 cm) from plumb. The effect is to make them appear vertical, since tall walls and objects can often appear to be leaning outward when seen up close from below. The corner columns are thicker than the others to make them appear to be the same diameter. Finally, it is when standing at the corner looking down the length of the steps on either side that one realizes the stylobate is actually curved and is about 4 inches (10 cm) higher in the center of the long side than at the corners. The effect is subtle but visible to the knowledgable eye at the site; the drawing in Figure 10.13 exaggerates these effects to make them more visible at a small scale.

The columns are also not perfectly vertical but lean inward about 2 inches (5 cm) from plumb. The effect is to make them appear vertical, since tall walls and objects can often appear to be leaning outward when seen up close from below. The corner columns are thicker than the others to make them appear to be the same diameter. Finally, it is when standing at the corner looking down the length of the steps on either side that one realizes the stylobate is actually curved and is about 4 inches (10 cm) higher in the center of the long side than at the corners. The effect is subtle but visible to the knowledgable eye at the site; the drawing in Figure 10.13 exaggerates these effects to make them more visible at a small scale.

The later Roman architect Vitruvius (De Arch. 3.4.5) tells us in his treatise on architecture that this optical refinement is necessary to make the line of the stylobate appear straight and not bent, and in the Parthenon this extends up into the entablature. Additional explanations for these adjustments were to make the building appear larger than it is, or that the inconsistencies create a tension in the mind of the viewer between rule and perception, forcing attention on the building and making it a more dynamic sight (Pollitt 1972, 75-78). Undoubtedly, the importance of the viewing experience would seem to be a foremost concern for the design and the enormous expense these adjustments entailed.

The Parthenon was the first large temple to be built entirely out of marble, which came from the quarries on the slopes of Mount Pentelikon, about 17 kilometers from the Acropolis. The marble was used in creating one of the largest ensembles of architectural sculpture for a temple: ninety-two metopes on all four sides of the building, a frieze wrapping around all 159.7 meters of the naos, two pedimental groups, and acroteria. On the west, back side of the Parthenon, the first side that a visitor would see, the pediment showed the contest between Poseidon and Athena for naming Athens (see subjects in Figure 10.11). The metopes below had an Amazonomachy. The metopes on the north side showed the Iliupersis, while those on the south had a Centauromachy. Finally on the east side, where one entered the naos, the metopes featured the Gigantomachy and the pediment showed the birth of Athena. The pediments thus represent the relationship of Athens to its patron goddess, while the metopes show various Greek groups fighting their enemies (Amazons, Centaurs, and Trojans) and the Olympian gods imposing their order over the giants. The frieze on the exterior of the naos shows a procession of Athenians, beginning with the assembly of riders on the west end, followed by parallel cavalcades on the first half of the north and south sides (see Figure 1.1, page 2). Next are contests with hoplites jumping into chariots (called the apobates), and then a sacrificial procession with animals and attendees. These figures round the corner to the east side of the building, where a peplos is being handled by a priest, priestess, and three younger figures while the Olympian gods watch from the wings (see Figure 10.15).

|

Stylistically the figures of the metopes, dated to 447-442 все, have some similarities to bronze and marble sculpture like the Riace Warriors and the Olympia metopes, but some of them reveal a greater emphasis on more graceful and fluid movement in the figure and slightly thinner body proportions (Figure 10.14). This is even clearer in the frieze, where the figures exhibit a poise and gravity like the Doryphoros (Figure 10.15; see Figure 1.1, page 2). The men and women of the frieze are idealized Athenians, showing their piety toward the gods. As mentioned in the last chapter, there has been much debate about whether the frieze represents an actual Panathenaic procession, in which the citizens of Athens bought a new peplos for the cult statue of Athena on the Acropolis, or

perhaps a mythological narrative showing the sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus (see p. 233). One can also consider the frieze as composed of universalizing scenes, models of what makes Athens special. As J. J. Pollitt has proposed, Perikles himself made such an argument in his funeral oration of 431, when eulogizing those who had died fighting Sparta in the first year of the Peloponnesian War (Thuc. 2.38-39; Pollitt 1997). According to Perikles, what distinguished the Athenians from others was the quality of their institutions and way of life, their contests (seen in the apobatai), their sacrificial offerings and piety (the procession and peplos scene), and their military training (the cavalcade).

In looking at the frieze, one can see that the sculptors were aware of the procession of viewers below and alongside the building, walking from west to east. The youth who stands at the northwest corner next to his horse turns his head back and down and

In looking at the frieze, one can see that the sculptors were aware of the procession of viewers below and alongside the building, walking from west to east. The youth who stands at the northwest corner next to his horse turns his head back and down and

| |||

| |||

looks at the viewer below (see Figure 1.1, page 2). The depth of the relief is higher at the top of the frieze than at the bottom, allowing the figure to project visually and be seen more clearly at the sharp upward angle. Not only does this figure engage the viewer, but other riders turn their heads in the same direction in a periodic rhythm as one walks along the frieze, as do attendants with the chariots and sacrificial animals as one approaches the east end of the building. Since the viewers’ actions below mimic those of the relief, a visual bond is established between the idealized and real Athenians. The frieze itself is composed as a progressive narrative, moving from the early stages of assembly and organization to the end presentation and keeping pace with the viewer walking along the building.

|

Turning the corner to the east pediment, its center once showed the birth of Athena, but only the two wings are left (Figures 10.16A and 10.16B). On the right are three reclining goddesses, labeled K, L, and M, probably Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite respectively. On the left side is Artemis (G) moving away from the center, Demeter (F) and Kore (E) seated, and finally a reclining man labeled D. The seated figures toward the center are turned in that direction, as if they have just become aware of the birth of Athena, goddess of wisdom and craft. The reclining figures, D and M, show no awareness of this event and have their backs turned against it. The composition is a dramatically staged metaphor, with the reclining figures set in opposition to the center of the composition. If these reclining figures are Dionysos, as many scholars have seen as probable, and Aphrodite, one would have the gods of wine and love at the wings of the tableau, and wisdom and industry in the center. The divine gifts of wine and love are necessary for humans, but they can also bring chaos if used unwisely. Athena brings order and balance, the Pythagorean mean, to the citizens of her city below. Of course, this specific interpretation depends on the identification of the figures, especially

10.17 Parthenon, Athens, view of southeast corner with reproduction of Dionysos (D) figure. Photo: author.

10.17 Parthenon, Athens, view of southeast corner with reproduction of Dionysos (D) figure. Photo: author.

|

Dionysos, who has also been identified by some scholars as Theseus, Herakles, and most recently by Dyfri Williams as Ares (Williams 2013). The pairing of Ares and Aphrodite could also be oppositional and disruptive like that of Dionysos and Aphrodite, with Athena providing the resolution, but the continued debate over the identity of figure D reminds one of the element of uncertainty in interpreting ancient art.

That the pedimental composition is like a play that engages the audience can be seen by looking at the replicated figure of Dionysos (or D) in the corner of the pediment today (Figure 10.17). Not only is he turned away from the central action, he is also looking down toward the viewer and is the first to greet the viewer as he or she rounds the southeast corner. Although Aphrodite has no head today, her position is similar to Dionysos and she would have faced the main processional traffic turning the northeast corner to enter the naos. In a way, they tempt the viewers with their gifts, but the piety and civic life of the viewer create balance as he or she moves along and sees Athena in the pediment above and the presentation of her peplos over the door to the naos (see Figure 10.15).

The presentation of the peplos reminds us that the Parthenon is a religious building and that some of the most important Athenian rituals, including the Panathenaia, took place on the Acropolis. In the aftermath of the Persian destruction the site was not rebuilt immediately, allegedly as part of the Oath of Plataia by the victorious Greeks as a testimony to the sacrilege of the Persians. A small sanctuary had been refashioned at the sixth-century Temple of Athena on the Acropolis, but as we saw in Chapter 7, most public ritual required open space, so that the Acropolis continued to serve its religious functions. In undertaking its reconstruction, Perikles was also making an ideological statement about the pious character and power of Athens. In looking at the Parthenon, both up close and from various sites in the city, one can see that the agenda of Perikles was not just to beautify the city, but to project an image of its power and prestige. This is particularly visible from the Pynx, where Athenian male

citizens gathered to vote and make decisions such as the construction of the Acropolis, whose major buildings can all be seen from there when looking eastward (see Figure 1.9, page 13).

In his history of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides provides the text of Perikles’s funeral oration of 431 все, which eulogized the Athenians who had died in the first year of the war. While presented as a quotation, it more likely represents an approximation of some of what Perikles said. According to Thucydides, Perikles asked the citizens of Athens to look upon their city, recently transformed with new buildings, and by looking at it become lovers of the city, willing to sacrifice their lives on its behalf:

you must yourselves realize the power of Athens, and feed your eyes upon her from day to day, till love of her fills your hearts; and then, when all her greatness shall break upon you, you must reflect that it was by courage, sense of duty, and a keen feeling of honour in action that men were enabled to win all this. (Thuc. 2.43.1; tr. Crawley)

Earlier in his history, Thucydides tells us of Sparta and Athens:

Earlier in his history, Thucydides tells us of Sparta and Athens:

For I suppose if Lacedaemon [Sparta] were to become desolate, and the temples and the foundations of the public buildings were left, that as time went on there would be a strong disposition with posterity to refuse to accept her fame as a true exponent of her power.... Whereas, if Athens were to suffer the same misfortune, I suppose that any inference from the appearance presented to the eye would make her power to have been twice as great as it is. (Thuc. 1.10.2; tr. Crawley)

With the fifth-century building program, Athens created both a stage for its rituals and piety and an expression of Athenians’ perceived preeminence among the Greek poleis.

late fifth-century sculpture

The drapery style of the pedimental figures, especially Aphrodite, has the combination of thick folds and smooth surfaces clinging to the body that we saw on the slightly later Nike of Paionios, and this style is prevalent in architectural sculpture and relief for the remainder of the century. One well-known example is from the small Temple of Athena Nike that was set on a bastion next to the Propylaia and built after it in the 420s (see Figure 1.9, page 13). Between 420 and 410 все, a parapet wall was added around the bastion that

featured reliefs on each side of multiple Nikes bringing a sacrifice to a seated Athena (Figure 10.18). In the example, we see a Nike adjusting the straps of her sandal, a familiar type of pose that recalls the recumbent Aphrodite from the Parthenon pediment. The unsteady and twisting pose makes the fabric stretch and clump over her body, and the effect around the breasts and abdomen leaves little to the imagination. The long hanging curves of the garment folds create a very decorative ripple effect, giving a very different and more sensual impression than the Parthenon frieze figures.

The last building to be completed on the Acropolis was the Erechtheion (see Figure 7.8, page 164). Whereas the Parthenon and Propylaia had Doric exteriors and Ionic interior columns, this building was completely in the Ionic order and included the famous Caryatid porch. As we saw in Chapter 7, the building itself is very irregular as a temple, but its decorative relief does convey the richness of Ionic architecture (see Figure 7.9, page 165). The building was not completed until about 405 bce, and its frieze showed a series of white marble figures that were set into a blue marble background (see Figure 11.3, page 272). While smaller and not quite as detailed as the Nike parapet, they continue the florid style on the Acropolis. Since some of the payments for these figures survive on the Acropolis building tablets, we will discuss these reliefs further in the next chapter since they are important for understanding the economics of sculpture production (see pp. 270-271).

During the last three decades of the fifth century there is a change in burial customs that revives an important category of relief sculpture in Athens, funerary monuments. While these were found in archaic Attica, as we have seen, they had apparently been banned by the city during the fifth century as too extravagant for private expenditure. Such legislation, typically called sumptuary laws, is often intended to prevent a small group of wealthy or privileged citizens from distinguishing their elite status; for the new democratic constitution of Athens in the late sixth century and following, a ban on elite funerary monu-

During the last three decades of the fifth century there is a change in burial customs that revives an important category of relief sculpture in Athens, funerary monuments. While these were found in archaic Attica, as we have seen, they had apparently been banned by the city during the fifth century as too extravagant for private expenditure. Such legislation, typically called sumptuary laws, is often intended to prevent a small group of wealthy or privileged citizens from distinguishing their elite status; for the new democratic constitution of Athens in the late sixth century and following, a ban on elite funerary monu-

ments emphasized the prerogative of the polis. For whatever reason, these prohibitions relaxed around 430 bce and later, and there is a growing use of reliefs for commemoration of the deceased by families, such as the grave stele of Ampharete (Figure 10.19). Ampharete sits on a chair as if in an interior setting, holding an infant in her hand. The drapery does clump and pull tightly, but is not quite as revealing as the Nike Temple figure and the pose is quieter and more contemplative, as would be appropriate for commemorating the deceased. Ampharete’s veil makes her seem like a bride, making her an idealized Athenian woman. The inscription on the architrave, however, tells us that Ampharete is a grandmother holding her dead grandchild: “I hold here the beloved child of my daughter, which I held on my knees when we were alive and saw the light of the sun, and now dead, I hold it dead" It is possible that this monument was made for a mother and child in a workshop and then adapted by inscription to its final use for a grandmother, but the ideal of bride and mother that Ampharete had attained still makes this youthful idealization appropriate for her grave monument.

Indeed, grave reliefs, while being individual purchases, use a small range of figural types that were adapted through details or inscriptions to serve their individualized purpose. We have already seen the stele of Hegeso from the end of the century, seated as a matron like Ampharete but engaged with pulling jewelry from a box (see Figure 5.28, page 127). While far more naturalistic than their archaic predecessors like Phrasikleia (see Figure 8.13, page 195), the message remains similar and conforms to an idealized type. The detachment of the figures continues the idea of grandeur seen in the Parthenon frieze, but there is a more intimate appeal of quiet emotion and domesticity in these grave reliefs.

|

painting

The elements of human representation that we found in fifth-century sculpture, such as contrapposto, rhythmos, pathos, and ethos, are also found in painting of the fifth century. Additionally painters have two other challenges to naturalistic representation: how to show a body with mass and volume on a two-dimensional surface, and how to represent a three-dimensional space in which the figures move not just from side to side, but forward and backward relative to the two-dimensional picture plane. These challenges become even more complicated for vase painters, who work on a curving rather than flat surface. By the end of the fifth century, we will see that some of the features of illusionistic pictures that we take for granted, such as foreshortening, skiagraphia (shading to create volume), and skenographia (perspective), become common in painting.

In the last chapter we looked at a hydria by the Kleophrades Painter with scenes from the Iliupersis that is nearly contemporary with the Kritios Boy and Aigina pediments (see Figure 9.7, page 219). The warrior Neoptolemos is poised to bring his sword down upon king Priam, who grasps his head with his hands. He is not shielding himself but is tearing at his scalp in mourning for his dead grandson, Astyanax, who lays on his lap. While Neoptolemos still has traces of the archaic smile, his emotional state contrasts sharply with the grieving, doomed residents of Troy. The Greek warrior behind him, however, cowers before a woman holding only a large pestle, who attacks him with her makeshift weapon. The parts of the body in these figures are more coordinated with each other than in the early experiments with rhythmos and foreshortening that we saw in the earlier work of Euphronios (see Figure 8.26, page 206).

It is during the fifth century that large-scale painting became a prominent medium. Some of the new buildings constructed in Athens between 475 and 450, such as the Theseion and the Stoa Poikile (painted stoa), had monumental paintings on their walls, either large wooden panels or frescoes. Literary sources record some details of the paintings of Polygnotos and Mikon in these and other buildings that became famous in the following centuries. Even 400 years later, these artists are still mentioned by writers such as Cicero as the first great painters in the history of Greek art, whose figures were less “hard” than those of the archaic period, and more closely represented reality (see Chapter 1).

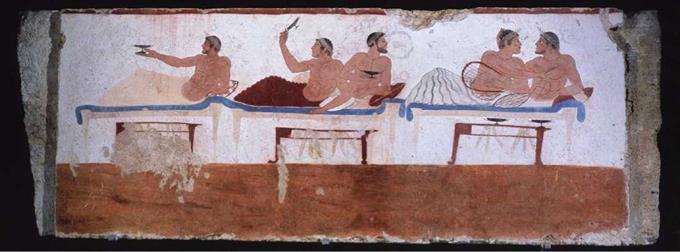

None of these paintings survive, but there is a rare example of wall painting from the Tomb of the Diver in Poseidonia/Paestum showing a youth diving into a pool on the tomb’s ceiling, and below a symposion scene on the four walls of the cist tomb (Figure 10.20). The treatment of anatomy and pose is similar to that of the Kleophrades Painter, with a greater sense of three-dimensionality and

None of these paintings survive, but there is a rare example of wall painting from the Tomb of the Diver in Poseidonia/Paestum showing a youth diving into a pool on the tomb’s ceiling, and below a symposion scene on the four walls of the cist tomb (Figure 10.20). The treatment of anatomy and pose is similar to that of the Kleophrades Painter, with a greater sense of three-dimensionality and

movement compared to the panel from Pitsa about a half-century earlier (see Figure 8.21, page 202). The contour of the figures is defined by a thick dark line, helping the flesh color to stand out from the white background, and the major anatomical features are also defined by lines as they are in vase painting. The medium does make it easier for the painter to suggest the wispy fringes of hair and beard than in red-figure painting, but it is the use of color that stands out from red-figure painting. Being able to use red for lips against the tan color of the skin, for example, gives more expressiveness to the mouth, and the distribution of colors creates more visual variety in the composition. We get a more vivid sense of the adult man on the far right professing his feelings to his younger companion, with the clearly open mouth and the light fingers moving through the black hair.

The Tomb of the Diver is unique and likely shows a pastiche of influences or sources. The tomb itself was from a small cemetery outside of Poseidonia/Paestum and near a settlement of Etruscans. In Etruria wall paintings in chamber tombs had become a major art form in the sixth century, and the painting technique in the Tomb of the Diver is consistent with Etruscan practices. However, the cist form of the tomb is more local or Greek in form. Whether the tomb’s occupant was Etruscan, Greek, or Lucanian, the native Italic residents of the area, is uncertain. The krater depicted on one of the short walls is more Lucanian in form, but the symposion scene would appear to be derived from Greek practices and perhaps from vase paintings of the symposion that could have been available for the painters, who were likely local (Holloway 2006). Perhaps the best way to view the tomb paintings is as a nexus, one that combines multiple artistic influences and reflects multiple aspects of identity, a theme that we will explore further in Chapter 13.

There is not much sense of volume in the figures in the Tomb of the Diver since the paint is generally applied in a flat monotone. It is by setting darker and lighter tones next to each other to mimic the play of light on a three-dimensional form, modeling or skiagraphia in Greek, that a painter can create a sense of volume and mass. In the absence of fifth-century mural paintings, we can find some examples of this on white-ground vase painting, in which a white calcareous layer like plaster coats the surface of the vase, as can be seen on the interior of a cup attributed to the Sotades Painter (Figure 10.21). This painting technique developed in the sixth century when some black-figure painters applied the coating over the red surface of the vase, but in the fifth century painters began to paint directly on the white surface with colored pigments. While it looks like a wall painting, this cup is only 13.3 cm in diameter, a truly miniature painting. In the picture, a young boy labeled Glaukos, crouching on the right, wears a brown-purple himation pulled over his head. Darker lines create the impression of deep folds in the fabric, while white lines on the garment’s edges and creases simulate light catching the ridges of fabric. So too the hair is lighter brown around the temple and darker where it is thicker on top of the head. The effect is to give a sense of mass and volume to the figure. This use of tone to suggest three-dimensionality would become more refined into the fourth century as skiagraphia.

There is not much sense of volume in the figures in the Tomb of the Diver since the paint is generally applied in a flat monotone. It is by setting darker and lighter tones next to each other to mimic the play of light on a three-dimensional form, modeling or skiagraphia in Greek, that a painter can create a sense of volume and mass. In the absence of fifth-century mural paintings, we can find some examples of this on white-ground vase painting, in which a white calcareous layer like plaster coats the surface of the vase, as can be seen on the interior of a cup attributed to the Sotades Painter (Figure 10.21). This painting technique developed in the sixth century when some black-figure painters applied the coating over the red surface of the vase, but in the fifth century painters began to paint directly on the white surface with colored pigments. While it looks like a wall painting, this cup is only 13.3 cm in diameter, a truly miniature painting. In the picture, a young boy labeled Glaukos, crouching on the right, wears a brown-purple himation pulled over his head. Darker lines create the impression of deep folds in the fabric, while white lines on the garment’s edges and creases simulate light catching the ridges of fabric. So too the hair is lighter brown around the temple and darker where it is thicker on top of the head. The effect is to give a sense of mass and volume to the figure. This use of tone to suggest three-dimensionality would become more refined into the fourth century as skiagraphia.

The same effect can be seen in the arched line that represents the tumulus enclosing the figures. Multiple, thicker lines ofyellow at the edge and thinner lines inside create the effect of a curved wall so that we get the sense of looking inside something like a tholos tomb. The figures are not set on a single groundline but on a ground plane with added bits of clay to give it a pebbly texture. This is like the texture of the beach described in the contemporary mural paintings at Delphi by Polygnotos. The arch and ground features give the picture a rudimentary three-dimensional space, both receding and projecting forward.

The mural painter Polygnotos had a reputation in literary sources as a painter of ethos, but this is a quality that we can also see even in this miniature painting by the Sotades Painter. In particular, it is the choice of the moment of action that captures the thought and decision-making that define character. Glaukos was the son of king Midas and had disappeared, but was found drowned in a vat of honey by the seer Polyeidos. The distraught king buried his son and the seer in the tomb, and the only hope of escape for Polyeidos was to bring Glaukos back to life. A snake appeared in the tomb and was killed by Polyeidos; it lays coiled at the lip of the cup. When a second snake appeared with an herb in its mouth, Polyeidos hesitated before killing it reflexively and observed its action. The snake placed the herb in the mouth of the dead snake and revived it, thus providing Polyeidos with his means of escape by reviving Glaukos. In the picture Polyeidos is poised with his staff in hand,

ready to crush the second snake, drawn at the very rim of the cup, but pauses to observe. This is a moment of decision that will determine his life or death, and he acts with thought rather than fear, revealing his ethos as a seer. This focus upon the choice of action as the key to revealing character was apparently present in the painting of Polygnotos, and is a component of the plots in the contemporary tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles. It is, indeed, a broad concern of the fifth century, but we should also remember that the focus on a pivotal moment of choice to reveal character is something that could appear earlier, as in Exekias’s painting of the suicide of Ajax (see Figure 9.5, page 216).

Another innovation attributed to Polygnotos regarding picture space was the placement of figures on multiple groundlines, with figures in the background or distance being higher up in the picture than figures in the foreground. This effect is seen on a pot in the Louvre known as the Niobid krater for its representation of the killing of the children of Niobe on one side. It is better known for its scene of heroes on the other side (Figure 10.22). The specific story is uncertain, although Herakles and Athena are easily identified in the center and left, and the seated figures in the foreground are probably Theseus and Peirithoos. The figures are set on undulating lines that represent an uneven terrain. Herakles is higher than the two seated figures below and in front of him, as can be seen by their overlapping limbs, making him further back in space. Athena is lower than Herakles and closer to the picture plane, but still behind Theseus and Peirithoos. Behind Athena is the top half of a warrior; his lower half is hidden by the hillock that is behind Athena, so he is even deeper in the picture and moving toward the front and center. This use of levels to represent depth of space is not a true perspectival system, which would be more precisely measurable and also involve the reduction in size of figures in the background compared to the foreground. That development would take place later in the fifth century, as we shall discuss below.

A white-ground lekythos attributed to the Achilles Painter brings us to the third-quarter of the fifth century, contemporary with the Doryphoros and Parthenon frieze (Figure 10.23). In this

|

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 949;

10.20 Painted wall from the Tomb of the Diver, Poseidonia/Paestum, c. 470 все. 30n/i6 in (78 cm). Symposion scene. Paestum, Museo Archeologico Nazionale. Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

10.20 Painted wall from the Tomb of the Diver, Poseidonia/Paestum, c. 470 все. 30n/i6 in (78 cm). Symposion scene. Paestum, Museo Archeologico Nazionale. Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.