middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 14 страница

Whereas bucchero ware had a highly polished black glaze with incised or stamped relief decoration rather than painted figures, the Attic potters copied the shape but applied a lively black-figure decoration, in this case dancing satyrs and maenads in a miniature style.

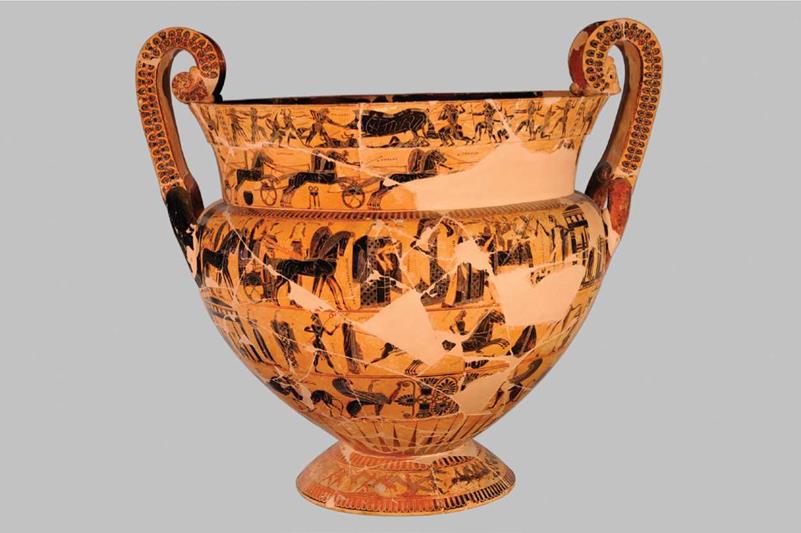

Looking at the Francois Vase, some of the scenes follow formulas that become conventional in the sixth century and must have been widely recognized across the markets. The Calydonian boar hunt on the top frieze, for example, shows a large number of hunters attacking a huge boar from both sides, with a dog and

hunter already dead. An excerpt from this formula might be seen in the Lakonian kylix, which is about fifteen years later in date (see Figure 8.22). Given the longer frieze to fill, Kleitias could add a full complement of hunters that would have been impossible on the kylix. The scene second from the bottom shows Achilles chasing the Trojan prince Troilos, who is riding a horse. This, too, becomes very popular in the sixth century and would be instantly recognizable for having a warrior running

8.20  Rhodian terracotta scent bottles, c. 600-550 все. Warrior, 29/16 in (6.5 cm); woman, 43/4 in (12 cm); horse, 3 in (7.6 cm). London, British Museum 1860,0201.41; 1836,0224.365;

Rhodian terracotta scent bottles, c. 600-550 все. Warrior, 29/16 in (6.5 cm); woman, 43/4 in (12 cm); horse, 3 in (7.6 cm). London, British Museum 1860,0201.41; 1836,0224.365;

1860,0404.27. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

8.21 Painted panel from Pitsa, Corinthia, c. 540-530 все. 515/16 in (15 cm). Athens, National Archaeological Museum 16464. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Giannis Patrikianos) © Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Culture and Sports/ Archaeological Receipts Fund.

8.22  Lakonian kylix attributed to the Hunt Painter, c. 555 все. 711/16 in (19.5 cm) diameter. From Cerveteri. Paris, Louvre E670. Calydonian boar hunt. Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Lakonian kylix attributed to the Hunt Painter, c. 555 все. 711/16 in (19.5 cm) diameter. From Cerveteri. Paris, Louvre E670. Calydonian boar hunt. Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

|

8.23 Attic black-figure volute krater signed by Kleitias and Ergotimos (Francois Vase), c. 570 все. 26 in (66 cm). Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 4209.

Top to bottom: Calydonian Boar Hunt; Funeral Games of Patroklos; Wedding of Peleus and Thetis; Achilles pursuing Troilos; animal frieze; Battle of Pygmies and Cranes. Photo courtesy Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence.

|

down a rider, an apt image for “swift-footed Achilles” as Homer calls him. Other scenes, like the chariot race in the funeral games of Patroklos, are much rarer, but whether or not a viewer knew the Iliad, the chariot race would have a universal appeal as a theme. The wedding reception of Peleus and Thetis is likewise uncommon after 570, but as an encyclopedia of the gods, it would have been an interesting frieze to contemplate. Full literacy would have been limited among both Greeks and Etruscans, but the ability to sound out the names would have been more common and allowed someone to identify the figures. The Francois Vase is highly unusual for the vast quantity of narrative and figures, but it is a suitable exemplar for the widespread interest of narrative in sixth-century art and for its adoption as a distinctive feature of Attic pottery.

Around the middle of the sixth century, Attic artists increased the scale of their figures, so that each vase often had only one or two scenes that dominated the vase. For example, a black-figure cup in Boston shows the sorceress Kirke mixing a potion for the sailors of Odysseus, who runs in from the left to confront her (see Figure 9.6, page 217). The larger scenes are more visible from across a room than the earlier miniature- scale scenes and the details of the action among the figures more legible. The most well-known painter of the third quarter of the sixth century is Exekias, who signed the amphora in the Vatican Museum as both potter and painter (Figure 8.24). The larger figures could bear more detail, and the drawing of the anatomy becomes more subtle: the details of the hands as they move their pieces are precisely engraved through the black silhouette. There is still an interest in pattern and texture, but even with their frontal eye, there is a sense of focus and concentration. The orange-red color of the clay surface, a result of the high iron content of Athenian clay, is no longer cluttered with filling ornament, and the figures stand out as if they were on a stage.

Around the middle of the sixth century, Attic artists increased the scale of their figures, so that each vase often had only one or two scenes that dominated the vase. For example, a black-figure cup in Boston shows the sorceress Kirke mixing a potion for the sailors of Odysseus, who runs in from the left to confront her (see Figure 9.6, page 217). The larger scenes are more visible from across a room than the earlier miniature- scale scenes and the details of the action among the figures more legible. The most well-known painter of the third quarter of the sixth century is Exekias, who signed the amphora in the Vatican Museum as both potter and painter (Figure 8.24). The larger figures could bear more detail, and the drawing of the anatomy becomes more subtle: the details of the hands as they move their pieces are precisely engraved through the black silhouette. There is still an interest in pattern and texture, but even with their frontal eye, there is a sense of focus and concentration. The orange-red color of the clay surface, a result of the high iron content of Athenian clay, is no longer cluttered with filling ornament, and the figures stand out as if they were on a stage.

On this pot we see Achilles and Ajax playing a board game while resting from their duties. They call out their rolls in inscriptions, like a modern comic strip, with Achilles on the left having a four (tesara) and Ajax a three (tris). This subject is unusual and new in Attic art, and it is thought that this story of heroes gaming, for which we have no surviving literary source, might be an invention of Exekias. Susan Woodford has proposed that Exekias has created a scene that reflects the life of the warriors at Troy, including the tedium and the diversion through board games, which Palamedes was renowned for inventing (Woodford 1982, 178-179). In this light, we have to see artists as narrators in their own right, free to imagine a story that could have its own appeal and might catch the interest of viewers. In this case, his composition was the first of more than 150 surviving examples of the scene in Attic art, showing that it was not only popular with viewers, but was also copied by other painters in the Athenian potters’ quarter.

Among the earliest copies are in workshops associated with Exekias, where we also see the development of a new technique, red-figure painting. As can be seen on an amphora in Boston by the Andokides Painter, it is essentially a reversal of the black-figure composition (Figure 8.25).

The figure’s outline is now defined by a thick brushstroke of paint and the background is then painted with black slip. Inside the outline, the silhouette of the figure is then the bare, red surface of the clay. Lines are drawn in the silhouette, thick black lines for major parts of the figures and lighter, dilute red-brown lines for finer details, as can be seen in the pot sherd of a test piece from the fifth century (see Figure 11.4, page 273). Additional applications of red and white slip can also appear. Some of the earliest vases in this technique, like the Boston amphora, feature black-figure on one side and red-figure on the other, and are called bilingual. Their style is very similar to the figures on the Siphnian Treasury, as can be seen by comparing the poses and details of anatomy to the scene of Achilles fighting Memnon from the east frieze (see Figure 8.1, page 183) or the Gigantomachy from the north frieze (Figure 9.1, page 212). This similarity to the earliest red-figure painting suggests a date of 530-520 все for the invention of the red-figure technique. Since the painter is no longer engraving through the black silhouette, but is applying slip directly to the surface, it is more like free painting, like the painted panel with sacrificial procession from Pitsa (see Figure 8.21).

| |||

| |||

The change to red-figure technique might at first have been a novelty for the market, since the style remained similar to black-figure work, but in the last two decades of the sixth century a group of artists labeled the Pioneers began to use the new technique to develop more complicated, threedimensional poses and actions. For example, a calyx krater by Euphronios shows Herakles wrestling the giant Antaios (Figure 8.26). Whereas Herakles’s pose is all in profile (and even the pupil of his eye has moved forward slightly, changing the frontal eye of Exekias), Antaios’s body is in a frontal view at the hips, somewhat three-quarter at the shoulders, and profile at the head. His left leg is crossed over in front of his right, with the effect that Herakles is twisting him like a corkscrew. Herakles’s mouth is closed with his gaze forward, but Antaios’s mouth is open and his teeth show. Antaios’s eyes look upward, as if the life were being squeezed out of him; indeed, his right hand lays

on the ground lifeless. Many of the muscles of the figures are shown with dilute line and heighten the sense of exertion. There is still some awkwardness in how the parts of Antaios’s body connect where the view is blocked by Herakles, but Euphronios here is attempting to show the body’s movement and exertion, the concept of rhythmos that we have already discussed with the Athenian Treasury (see Figure 8.7) and the ball player base (see Figure 8.8).

The experimentation with poses, gestures, and expressions can be seen in a contemporary cup with a symposion scene (see Figure 13.1, page 321). Rather than wrestling, the painter here is attempting to show a more erotic scene, but one that requires twisting figures and extended limbs as the figures interact. Again, there is a bit of awkwardness in the drawing of the anatomy, but later red- figure painters of the end of the sixth century and beginning of the fifth master the representation of more complex movement and poses and how to foreshorten a figure to adjust for the viewing angle. The cup by the Foundry Painter showing two young and inexperienced boxers has a very poised youth observing the main action, turning back to view the comic slapping of the young trainees in the center (see Figure 13.11, page 332). The muscles of his abdomen are drawn in dilute red and are shown in a three-quarter view to make the transition from frontal right foot to profile left foot below. The contrast between his demeanor and that of the boxers also suggests a difference in the emotional state of the figures, as the standing youth appears and behaves in a more mature, calm, and perhaps superior attitude. The Iliupersis scene by the Kleophrades Painter uses this juxtaposition to offer a sharp contrast between the grieving king Priam, who has lost his grandson and his city, and Neoptolemos, the son of Achilles, who is about to kill him (see Figure 9.7, page 219).

|

This second generation of red-figure painters brings us into the developments of the fifth century, which we shall explore in Chapter 10. It also highlights the continuing interest in and development of narrative art in Attic vase painting, since with red-figure painting there is an expansion in the production and export of narrative images. The technique opened new possibilities for showing the human figure in action, and we shall explore narrative art more specifically in the next chapter.

references

Boardman, J. 1991. Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson. Brinkmann, V. 2008. “The Polychromy of Ancient Greek Sculpture.” In R. Panzanelli, ed. The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, 18-39. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. Brinkmann, V. and R. Wiinsche, eds. 2007. The Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity. Exhibition at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Museums in Cooperation with Staatliche Antikensammlungen and Glyptothek Munich, Stiftung Archaologie Munich. September 22, 2007-January 20, 2008. Munich: Stiftung Archaologie.

Cohen, B., ed. 2006. The Colors of Clay: Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. Faure, P. 1985. “Les Dioscures a Delphes.” LAntiquite Classique 5, 56-65.

Herodotos. 1987. The Histories, tr. D. Grene. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marconi, C. 2007. Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus.

Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Osborne, R. 2001. “Why Did Athenian Pots Appeal to the Etruscans?” World Archaeology 33, 277-295. Osborne, R. 2007. “What Travelled with Greek Pottery?” Mediterranean Historical Review 22, 85-95.

Palagia, O. and N. Herz. 2002. “Investigation of Marbles at Delphi.” In J. J. Herrmann, Jr., N. Herz, and R. Newman, eds. Asmosia 5: Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, 240-248. London: Archetype Publications.

Stieber, M. 2004. The Poetics of Appearance in the Attic Korai. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Woodford, S. 1982. “Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game on an Olpe in Oxford.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 102, 173-185.

further reading

Beazley, J. D. 1986. The Development of Attic Black-Figure. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Boardman, J. 1974. Athenian Black Figure Vases: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson.

Boardman, J. 1975. Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Archaic Period. A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson. Boardman, J. 1991. Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson.

Hurwit, J. M. 1985. The Art and Culture ofEarly Greece, 1100-480 B.C. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Marconi, C. 2007. Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rasmussen, T. and N. Spivey, eds. 1991. Looking at Greek Vases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shapiro, H. A., ed. 2007. The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snodgrass, A. 1980. Archaic Greece: The Age of Experiment. London: J. M. Dent.

narrative

Timeline

Narrative and Artistic Style

Narrative Time and Space

Viewing Context

Art and Literature

Choice of Mood and Moment

Symbolic and Universal Aspects of Narrative

Textbox: Interpretation and Information Theory

References

| |||

| |||

Further Reading

timeline

| Sculpture | Pottery | |

| 800-700 | MG II skyphos from Eleusis, 770 | |

| 700-625/600 | Eleusis amphora, 670-650 [6.15] Chigi olpe, 650-640 [6.11] | |

| 625/600-480 | Temple C at Selinus/Selinunte, 550-530 [8.6] Siphnian Treasury, 530-525 [8.1-8.2] | Frangois Vase, 570 [8.23] Attic BF kylix with Kirke, 550 Attic BF amphora by Exekias, 540-535 |

| 480-400 | Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470-457 Parthenon frieze, 442-438 [1.1, 10.15] | Attic RF hydria by Kleophrades Painter, 480 Attic RF krater by Niobid Painter, 460 Attic RF skyphos by Penelope Painter, 450-440 Attic RF pelike by Pronomos Painter, 410-400 Cabiran skyphos, 410-400 |

| 400-330 | Monument of Dexileos, 394/393 [12.12] | Lucanian RF pelike by Choephoroi Painter, 350 Paestan RF krater by Asteas, 350-340 [12.21] |

| 330-30 | Tomb relief from Taras/Taranto, 300-250 Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, 180-150 |

| A |

s we noted in the last chapter, Greek narrative pictures became more common during the sixth century and were widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea areas. “Reading” these stories, however, is different from reading a text. Poets and writers can explain a sequence of actions in minute detail; the Iliad covers just over two weeks of the decade- long Trojan War, although it recounts many other earlier events through speeches and descriptions. Most pictorial narratives are a single image that captures only some of the story’s action and calls upon the viewer to fill in the missing parts. The descriptive capacity of images, however, has its own narrative power that can appeal across barriers of language and culture. It is one thing to describe a battle, but to see the agony of the defeated or the perfect body of the hero creates an engagement with the viewer that is different from a text and partly explains the power of film as a narrative medium today.

There are several critical challenges for the modern viewer in deciphering an ancient Greek narrative. First, many ancient Greek stories and their variations do not survive in literary accounts. Some narratives were composed and preserved, like the Iliad, but many more poems and written accounts are known only from fragments or are lost entirely. Whereas we depend upon these surviving texts as a source for our knowledge of Greek narrative, the Greeks did not. Most people experienced epic poems like the Iliad and Odyssey or dramas like the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides as performances and did not consult texts. Oral traditions, tales told by parents and grandparents or stories told by guides at sanctuaries, were a fundamental part of both individual and collective knowledge. Furthermore, Greek literature did not focus on the creation of new stories and characters, but reworked or elaborated upon the stories that the culture had shared for centuries or adapted narratives from other cultures. Like the poets, artists rarely invented completely new narrative images, but drew upon the same sources as the poets. They could repeat or adapt a common visual formula, introduce a new variable or twist that might capture a viewer’s attention, or develop a new scene and their own version of a story.

The second challenge when looking at narrative pictures is that the ancient Greeks shared a visual language that we can only partially recover. While today many people can recognize and decode a sign like the Apple computer logo without effort, contemporary students of Greek art do not have that shared cultural experience of ancient art to identify figures and stories without effort. By examining and comparing numerous examples of a scene, however, we can decode some of the visual language with a degree of certainty. For example, we have seen several representations of the Gorgon Medusa in the past few chapters and of Perseus attacking her (see Figure 6.15, page 144; Figure 6.23, page 149; Figure 8.3, page 185; Figure 8.4, page 186; Figure 8.5, page 187; Figure 8.6, page 188). Even with variations in detail, some features, such as Medusa’s face, the use of a sword to behead someone while turning away, and the flight with the head as a trophy, permit quick recognition of the story. As we see in these examples, both protagonists do not even need to be present for recognition of the scene, nor is the presence of some other characters such as Athena, Hermes, Chrysaor, or Pegasos necessary. Greek artists and viewers shared this visual language, which allowed a single image to evoke recollection of an entire story.

In this chapter we will consider not only the story being represented in an image, but also the different ways in which narrative pictures can interact with the viewer. Having seen the development of a more naturalistic style of representation during the archaic period, we will first consider the impact that style has upon a narrative image. We will then observe the various strategies that artists used to deal with action in time and place, fundamental elements of any story. Finally, we will explore the role of the viewer in a pictorial narrative, consider the viewing context, the choice of narrative moment, and narratives that are more universalizing in theme and call upon the viewer to contribute specificity.

narrative and artistic style

We can broadly define a pictorial narrative as a picture of an action that leads to a change in the situation of the participants. A mythological battle scene, such as the gods and the giants fighting on the Siphnian Treasury (Figure 9.1), the Gigantomachy, fulfills that definition. The Giants, children of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus described in literature sometimes as monsters and sometimes as warriors, challenged the Olympian gods for supremacy. With the aid of a mortal, Herakles, the gods were able to defeat the giants. In art, the story is usually shown as a duel between one or two gods and opposing giants, but on a long frieze like the Siphnian Treasury we see a series of interlocking fights. In this section, we see Dionysos with his leopard skin behind a chariot driven by Themis; Dionysos and a giant are aiming spears at each other, while the lion pulling the chariot mauls a second giant. Ahead of the chariot Apollo and Artemis draw arrows at a triad of giants; in the background a fourth giant runs away while looking backward, perhaps at Dionysos and Themis. Another giant lays dead on the ground. The dead body shows that the battle has been going on for a while, but by showing one giant dead and another fleeing, the artist indicates that while the battle is still raging at the moment, the gods have the advantage and will be victorious.

The ability of an archaic artist to depict a complex composition, show space through the overlapping of the figures into receding planes, and vary the details of the actions makes visual narratives of the seventh and sixth centuries far more effective than scenes from the Geometric period. If we look at another combat scene on a skyphos found in a grave at Eleusis and dating to c. 770 bce, we can see two pairs of warriors fighting (Figure 9.2). The pair on the right has an archer in front and a spearman behind taking aim at their opponents. On the left side there is a second archer in front, but the warrior behind him holds some type of large pole, perhaps an epic weapon like the spear of Achilles that was made from a tree trunk and could only be thrown by Achilles himself. In the middle of the picture lie two figures set at an angle who are likely corpses that the fighting warriors are trying either to rescue or to strip of their armor. There is no indication that this is a mythological picture, lacking clear signs such as the inscriptions and attributes on the Siphnian Treasury, but like the Gigantomachy scene, it does show forceful actions that have had and will have consequences.

As we saw in the discussion of Chapters 4 and 6, the Geometric style, unlike the archaic, does not allow for detail or specificity of action, and this problem has led to debates about the

|

existence of mythological narrative during this period. It is possible to “read” some Geometric pictures as mythological narratives, but there remains uncertainty as to whether a specific story rather than a universal situation is represented. It took the development of a more intricate style in both sculpture and painting for artists to show narratives that were unambiguously specific. Whether or not an image is mythological is not the same, however, as whether it is a narrative. For example, the battle scene on the Chigi olpe (see Figure 6.11, page 141) is more complex and detailed in its action than the Eleusis skyphos, and has a variety of actions spanning a range of moments in time similar to the later Siphnian Treasury. For example, at the far left of the frieze a warrior is still putting on his armor. The last three warriors in the phalanx have longer strides than those ahead of them, showing that they are rushing up to join in the rank. At the head of the group, the warriors march in tight, rhythmic formation, ready to meet their opponents. Viewing the frieze from left to right, one can see unfold the initial response to the call to battle and then the subsequent joining and locking in formation. It is an effective representation of a battle and easily as complex as the Gigantomachy on the Siphnian Treasury, but there is no sign that it is a mythological or specific scene. Nevertheless, as a story of battle, it is quite an effective narrative.

We will discuss these more universalizing narratives like the Chigi olpe further at the end of this chapter, but for now we can turn to a late fifth-century representation of the Gigantomachy to see how changes in style over the century showing movement and space affect a narrative. On a late fifth-century pelike linked to the Pronomos Painter, we see three duels (Figure 9.3). In the center top is Ares, who has struck his spear through the shield of a giant, who grasps its point. To either side are the Dioskouroi (the Gemini twins), one on horseback and one on foot, fighting other giants. The scene is set in a rocky, three-dimensional landscape, with the god and heroes on the high ground attacking downward. The giant on the left has collapsed under the weight of the assault, while the one in the middle is being driven back and the two on the right are attempting a counterattack. The body posture of the nude youth and his action suggest that he is changing his position tactically, giving ground slightly in order to counter the attack of two giants. The picture, then, allows one to see the narrative as figures moving through space in three dimensions, rather than simply moving two- dimensionally across a shallow stage like the Siphnian Treasury. We also see convincing back and three-quarter views of the figures that reinforce this sense of the picture as a three-dimensional world. The greater naturalism in the rendering of muscles and anatomy conveys the fighters’ physical effort, and the perspectival consistency of the face and eye provides a sense of their gaze and focus. The greater range and subtlety of actions make each duel different and the overall action more lifelike and varied than archaic narrative.

We can skip further ahead to look at a Hellenistic version of the same story from the second century bce. A monumental Gigantomachy filled the frieze of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon (Figure 9.4). Here the figures are over life-size and cover the three sides and the wings flanking the front stairs, almost 120 total meters of frieze with close to 100 figures (see the view of the altar in Figure 14.6, page 352). On the front side, we see at the right end Amphitrite moving leftward away from the stairs, subduing a giant falling away from her; on the other side is the god Triton, who moves rightward toward Amphitrite and strikes down a second giant between them. In the section of the frieze along the stairs we see at the corner the bearded Nereus, god of the sea, who supports a goddess in front of him, probably his wife Doris, although the inscription is missing, moving toward the right (upstairs). Doris moves rightward (upstairs) and has grabbed the hair of a giant who has fallen to his knees; she pulls on the head so that the giant’s body arches back violently. His eyes are deeply set in his skull and convincingly roll upward; with his open mouth and slack hand trying to pull her wrist away, we see a figure that is expressing an emotional anguish and pain to match the physical trauma his body is experiencing. The figures are carved in very deep relief, and many of the anatomical features, especially the bulging muscles, are exaggerated to increase the sense of exertion and movement. We will

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1148;