middle helladic to the late helladic i shaft graves 12 страница

One difficulty in discussing the history of this period, particularly in terms of its stylistic changes, is that its chronology has very few fixed points. Most works are dated through relative chronology and stylistic comparison, but without a number of works with fixed dates, it is difficult to know how much a difference in style between two objects is due to a difference in date, or region, or perhaps the age of the artist. While art historians agree that the representation of the human figure at the end of the period is far more lifelike than at the beginning, this development was unlikely to have followed a linear and progressive evolution. Given the problem of dating, we shall begin by looking at one major chronological terminus for the period, the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi. From this point we can then examine other architectural sculpture, both earlier and later. Afterward, we will survey other media and forms: stone figural statues, three-dimensional work in other media, and finally painted pottery.

architecture and architectural sculpture

The development of the monumental Doric and Ionic orders and the adoption of stone as the primary building material for religious structures such as temples and treasuries, as discussed in the previous chapter, created specific areas for sculpted decoration, whether ornamental or figural. The triangular pedimented gables offered a prominent space for placing large reliefs or free-standing figures that could be set in front of the back wall of the pediment. Below it, the frieze presented panels for relief sculpture, whether square metopes in the Doric order or the continuous band found in the Ionic order. The ridge and corners of the roof also supported free-standing figures, called acroteria. Few buildings used all of the available areas for figural decoration, but the full potential for sculptural ornament can be seen in the small Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (see Figure 7.15, page 171). As the reconstruction drawing of this Ionic building shows, it featured two pedimental ensembles, friezes on all four sides of the building, six acroteria, as well as two caryatids in the place of columns on the pronaos, the earliest surviving examples of this statue type. The building was constructed of marble imported from the islands of Siphnos and Paros, making this building a very lavish and expensive undertaking.

Both Pausanias, the second-century ce traveler, and Herodotos, the fifth-century bce historian, mention the Siphnian Treasury. According to Herodotos (3.57-58), the building was a tithe offering of the Siphnians from their gold and silver mines. These were flooded around 525 bce, when the island was attacked by Samians who had unsuccessfully sought a loan from the wealthy Siphnians. Siphnos was not able to recover from this loss for decades. This suggests that the attack on the island is a terminus ante quem for the building’s start, since the funds for construction had to have been at Delphi by 525. Therefore a date of 530-525 is usually assigned to the building and its sculpture, and this becomes the anchor for sixth-century chronology through stylistic comparison.

The east pediment, on the back side of the building but seen first in approaching on the Sacred Way, (Figure 8.1) shows the struggle between Apollo and Herakles over the Delphic tripod, the seat of the god’s prophecy, as we saw in the previous chapter. Herakles had gone to Delphi, seeking purification or healing over his murder of Iphitos. According to some accounts, he seized the tripod when his request was refused. The scene of Apollo wrestling with Herakles over the tripod becomes popular in archaic art, often with Artemis and Athena supporting the two and Zeus in the center intervening. The figures are in high relief and fully in the round in their upper sections. The corners of the pediment have unidentified combat scenes, with the figures set in smaller scale to fit in the narrower corners.

The east frieze below shows a council of the gods on the left and a battle from the Trojan War between Memnon (left) and Achilles (right) over the corpse of Antilochos. These figures are strongly muscular and project from the background as if they were on a stage, an effect that would have been even stronger when they were originally painted, with dark blue for the background and reds on the insides of the shields and the groundline (for a restoration of color in sculpture see Figure 8.15, page 197 and Figure 10.3, page 239). The gods lean forward and gesture as they vigorously debate which warrior will win. Zeus, enthroned in the center, once held a bronze scale in which the souls of both warriors would have been set to determine who would live (Achilles) and who would die (Memnon). Each warrior has an ally fighting with him, and chariot teams flank both sides. The sculptor has arranged the horses’ heads in a combination of profile and three-quarter views that conveys an agitated, twisted movement in space. When compared with seventh-century sculpture, one can see more detailed rendering of anatomy and drapery and more varied movement (see Figure 6.24, page 149).

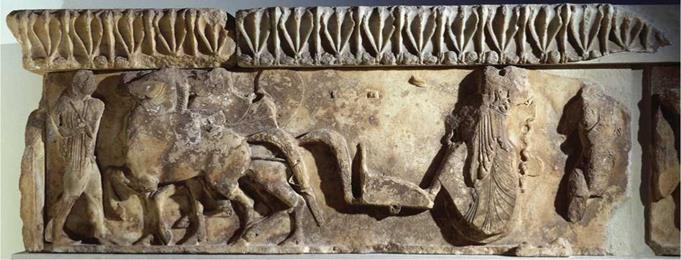

Looking at a section of the west frieze, from the front of the building, one can see some differences in both horses and human figures (Figure 8.2). The subject is uncertain; a scene like the abduction of the daughters of Leukippos by the Dioskouroi has been suggested. The composition is not as dense, with less overlapping than in the east frieze. The horses are completely in profile and, rather than rounded contours where the figure projects from the background, these figures have sharper edges that look more like cut-outs. The riders are slenderer than the warriors on the east side, and one might describe the detail of muscles, hair, and reins as linear across the top surface. Overall, there is less suggestion of a three-dimensional compositional space.

These stylistic differences are explained by an inscription on the shield of a giant on the north frieze, which states that “[missing name] made these subjects and those at the back [east]." Indeed, the style of the Gigantomachy on the north frieze is very similar to the combat on the east frieze, except that there is even more overlapping, stronger movement and further experiments with three- quarter views (see Figure 9.1, page 212). Of particular note is the lion wrapping his limbs around a giant dressed as a hoplite warrior, who looks backward and down toward the viewer standing below on the Sacred Way. Since all four friezes were carved at the same time, both sculptors were contemporaries, but elements of the south and west friezes appear to be older in approach, while the east and north friezes look ahead to later developments in the representation of movement and space in both sculpture and vase painting. By comparing the style of the Siphnian reliefs to sculpture and painting in the sixth century, the degree of difference in either direction becomes the basis for assigning dates throughout the archaic period. However, the differences between these two sculptors working at the same time on the same monument caution us against seeing developments in naturalistic representation, i.e., showing a lifelike human figure, as a smooth, progressive evolution.

These stylistic differences are explained by an inscription on the shield of a giant on the north frieze, which states that “[missing name] made these subjects and those at the back [east]." Indeed, the style of the Gigantomachy on the north frieze is very similar to the combat on the east frieze, except that there is even more overlapping, stronger movement and further experiments with three- quarter views (see Figure 9.1, page 212). Of particular note is the lion wrapping his limbs around a giant dressed as a hoplite warrior, who looks backward and down toward the viewer standing below on the Sacred Way. Since all four friezes were carved at the same time, both sculptors were contemporaries, but elements of the south and west friezes appear to be older in approach, while the east and north friezes look ahead to later developments in the representation of movement and space in both sculpture and vase painting. By comparing the style of the Siphnian reliefs to sculpture and painting in the sixth century, the degree of difference in either direction becomes the basis for assigning dates throughout the archaic period. However, the differences between these two sculptors working at the same time on the same monument caution us against seeing developments in naturalistic representation, i.e., showing a lifelike human figure, as a smooth, progressive evolution.

|

8.1 East pediment and frieze from the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, c. 530-525 все. Delphi Museum. Height of frieze: 253/16 in (64 cm). Herakles and Apollo struggling over the tripod; council of the gods and battle of Memnon and Achilles. Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY.

|

In considering architectural sculpture, we also have to give some thought to the relationship of the viewer to the work. The sculptor of the east and north frieze has composed the figures to address the viewer walking up the Sacred Way at Delphi (see Figure 7.15, page 171). On the east frieze, Achilles is the foremost warrior on the right side. Usually a victorious warrior is shown on the left, moving rightward (see Figure 6.15, page 144; Figure 6.18, page 146; Figure 9.17, page 231). By placing Achilles on the right, however, the sculptor puts the viewer down below on the side of the victor, standing behind him figuratively as his ally. Continuing along the north frieze, the visitor moves in the same direction as the victorious gods, who are shown in the more typical left-to-right direction. Thus the giants flee away from the viewer, and the giant being mauled by the lion looks down, back, and outward toward the viewer. The narrative unfolds as the viewer walks alongside the building, with wave after wave of giants fighting and being defeated by the gods. Reverence toward the gods, implicit in a pilgrimage to Delphi, puts the viewer on the compositional side of both heroes and the gods, from whom the visitor is seeking divine counsel through the oracle. In developing visual narrative in the sixth century, we will see in this chapter and the next that artists often took account of the viewer in structuring their compositions.

Turning now to earlier architectural sculpture, the Temple of Artemis at Korfu, an important early colony of Corinth, is considered to be the earliest temple made entirely with stone (Figure 8.3). It has two identical pediments carved in high relief. In the center is a running Medusa flanked by two lions; under her arms is her son Chrysaor on the right and the remains of Pegasos on the left. At the corners are large fallen figures, and toward the center are fighting scenes, carved at a smaller scale, showing the Olympian gods battling the Titans (Titanomachy), the older generation of gods whom the Olympians overthrew. Medusa runs in the conventional whirligig or running/kneeling pose that we saw in the painted metope of Perseus at Thermon (see Figure 6.23, page 149). While done in deep relief, the edges of the figures recede sharply into the pedimental wall, giving them a strong and projecting silhouette whose effect is heightened by Medusa’s monumental scale at over 3 meters high. The faces and bodies are flat planes with a variety of incised patterns on the surface for the details of the hair and garment borders. The figure of Chrysaor, who is roughly life-size, is similar in the detailing of his anatomy to the Sounion kouros (see Figure 6.4, page 135), with some indication of the chest and hips but little articulation of muscles on the surface of the stone. The Korfu pediment and Sounion kouros are both considered to be a couple of generations earlier than the Siphnian Treasury, with the kouros about 590 все and the Korfu pediment about 580 все.

Turning now to earlier architectural sculpture, the Temple of Artemis at Korfu, an important early colony of Corinth, is considered to be the earliest temple made entirely with stone (Figure 8.3). It has two identical pediments carved in high relief. In the center is a running Medusa flanked by two lions; under her arms is her son Chrysaor on the right and the remains of Pegasos on the left. At the corners are large fallen figures, and toward the center are fighting scenes, carved at a smaller scale, showing the Olympian gods battling the Titans (Titanomachy), the older generation of gods whom the Olympians overthrew. Medusa runs in the conventional whirligig or running/kneeling pose that we saw in the painted metope of Perseus at Thermon (see Figure 6.23, page 149). While done in deep relief, the edges of the figures recede sharply into the pedimental wall, giving them a strong and projecting silhouette whose effect is heightened by Medusa’s monumental scale at over 3 meters high. The faces and bodies are flat planes with a variety of incised patterns on the surface for the details of the hair and garment borders. The figure of Chrysaor, who is roughly life-size, is similar in the detailing of his anatomy to the Sounion kouros (see Figure 6.4, page 135), with some indication of the chest and hips but little articulation of muscles on the surface of the stone. The Korfu pediment and Sounion kouros are both considered to be a couple of generations earlier than the Siphnian Treasury, with the kouros about 590 все and the Korfu pediment about 580 все.

|

The bodies of Medusa, Chrysaor, and the lions are in profile, but their heads are turned frontally to look out toward the viewer. While this looks awkward, the function of the sculpture on the temple overrides its narrative purpose. The representation of deities is meant to be an epiphany, a visualization of the divine that engages the viewer. Like a cult statue, this means that the figure should look toward the viewer. A second function of the decoration is also to serve as an apotropaic device, that is, a sign that protects and guards a place or person from harm. The heraldic mistress of animals composition can serve this function (see Figure 6.17, page 145), as can the lions flanking a column on the Lion Gate at Mycenae (see Figure 3.6, page 56). We can look at the combination of lions and Gorgon here as similarly guarding the temple’s entrance. The decapitated head of Medusa, called a gorgoneion, becomes a highly favored apotropaic device, since it turned those who looked at it to stone. The placement of Medusa’s frontal head, still attached to her body, at the central peak of the pediment, even breaking beyond its upper frame, points to the apotropaic function of the gorgon- eion, even though it creates a narrative problem. Chrysaor and Pegasos are both offspring of Medusa, born from her spilled blood after her head was severed by Perseus, who is nowhere present on the pediment. Nevertheless, Medusa’s heroic offspring bring order to the world by defeating fearsome beasts and malevolent deities, as do the Olympian gods. These symbolic roles of the sculpture are more important than narrative consistency.

Medusa and the gorgoneion are also favored subjects for Greek temples in Sicily. A terracotta plaque with a running Medusa and Pegasos was found at an archaic temple of Athena in Syracuse (modern Siracusa) (Figure 8.4). The black, red, and cream colors create a rich display of details, patterns, and movement that reminds us of the effect of color in sculpture. The plaque is 56 cm high and has four holes where it was attached to the building. Whether it was mounted on the pediment or attached to a beam projecting above the gable of the temple like an acroterion is uncertain. The work is also an example of the importance of terracotta as a large-scale sculptural medium, especially at the Greek sites in southern Italy and Sicily.

A larger gorgoneion was placed on a temple at Selinus (modern Selinunte), a colony in western Sicily founded by settlers from the older, eastern Sicilian colony at Megara Hyblaea. The Doric building, as seen in the reconstruction by Marconi and the University of Lecce, is designated as Temple C, one of several temples found at Selinus/Selinunte (Figure 8.5). Based on Corinthian pottery found

at the foundations, construction of the building began around 560-550 все, but its completion date remains uncertain.

There were ten sculpted metopes across the front, three of which are well preserved and have been reassembled at the museum in Palermo (Figure 8.6). These occupied positions 6-8, counting from left to right. The left metope shows Apollo in a quadriga, or four-horse chariot, with two female figures, probably his sister Artemis and mother Leto. Next is Perseus killing Medusa, with Athena standing behind him and Pegasos in Medusa’s arms. The last metope shows Herakles carrying the Kerkopes, trickster brothers who attempted to steal the hero’s armor. He bound them upside down to a pole, where they commented on his tanned or blackened buttocks; according to a very late source, their comments made Herakles laugh and he let them go.

There were ten sculpted metopes across the front, three of which are well preserved and have been reassembled at the museum in Palermo (Figure 8.6). These occupied positions 6-8, counting from left to right. The left metope shows Apollo in a quadriga, or four-horse chariot, with two female figures, probably his sister Artemis and mother Leto. Next is Perseus killing Medusa, with Athena standing behind him and Pegasos in Medusa’s arms. The last metope shows Herakles carrying the Kerkopes, trickster brothers who attempted to steal the hero’s armor. He bound them upside down to a pole, where they commented on his tanned or blackened buttocks; according to a very late source, their comments made Herakles laugh and he let them go.

Comparing the style of the figures to those at Korfu, we can see that the poses are somewhat more convincing, the anatomical details more numerous and lifelike, and the edges more rounded against the stone background. The compositions also adapt to their position on the temple facade, with the quadriga metope at the center being fully frontal, and the narrative metopes moving more strongly rightward as the viewer glances toward the corner of the temple. The dating of the metopes has also been debated, since some of the fragmentary metopes at the corners appear later in style, which might have been a result of a slow building campaign. Many have dated the metopes to the middle of the sixth century, but Clemente Marconi has more recently suggested a date of 540-530 все, just before the Siphnian Treasury (Marconi 2007, 175-176). While none of the Siphnian Treasury figures uses a frontal head, this may be due to both a greater importance for narrative in later archaic architectural sculpture and the different function of a treasury compared to a temple. A temple like Selinus/Selinunte houses a cult statue and is a focal point for ritual and votive offerings that communicate with the gods. Like the Korfu pediment, all of these figures at Selinus/Selinunte are turned frontally, serving both epiphanic and apotropaic functions. A treasury, on the other hand, does not have a cult statue and is only a repository, so the cultic significance as well as the need to present a divine epiphany for its sculpture is less prominent.

Comparing the style of the figures to those at Korfu, we can see that the poses are somewhat more convincing, the anatomical details more numerous and lifelike, and the edges more rounded against the stone background. The compositions also adapt to their position on the temple facade, with the quadriga metope at the center being fully frontal, and the narrative metopes moving more strongly rightward as the viewer glances toward the corner of the temple. The dating of the metopes has also been debated, since some of the fragmentary metopes at the corners appear later in style, which might have been a result of a slow building campaign. Many have dated the metopes to the middle of the sixth century, but Clemente Marconi has more recently suggested a date of 540-530 все, just before the Siphnian Treasury (Marconi 2007, 175-176). While none of the Siphnian Treasury figures uses a frontal head, this may be due to both a greater importance for narrative in later archaic architectural sculpture and the different function of a treasury compared to a temple. A temple like Selinus/Selinunte houses a cult statue and is a focal point for ritual and votive offerings that communicate with the gods. Like the Korfu pediment, all of these figures at Selinus/Selinunte are turned frontally, serving both epiphanic and apotropaic functions. A treasury, on the other hand, does not have a cult statue and is only a repository, so the cultic significance as well as the need to present a divine epiphany for its sculpture is less prominent.

The choice of subject matter for Temple C appears very eclectic, particularly the Kerkopes metope. It has been suggested that the metopes as an ensemble represented all of the gods and heroes worshipped in the city, but this still leaves unresolved the choice of individual scenes, such as Kerkopes, which is not one of the most heroic stories. Most interpretations treat it as a comic episode, but Marconi has suggested that we should regard it more seriously, with the brothers being viewed as liars and thieves rather than tricksters, hence as menaces like others that Herakles subdued in many of his labors (Marconi 2007, 150-159). The story took place at Thermopylai in northern Greece; like the other episodes in the metopes, it occurred in the “Old World” of the Greek colony, reasserting its connection to the motherland (Marconi 2007, 204). Whereas the story may seem secondary to us today, it was widely known in sixth-century art and used for a metope on the Temple of Hera at Foce del Sele near Poseidonia/Paestum. Certainly the unusual subject and composition would have had its own appeal and perhaps have reflected some of the concerns of the colonists in their new land.

|

|

The narrative potential of architectural sculpture becomes more developed with the increasing ability and effort of sculptors to show complex poses and movement in the later sixth and early fifth centuries, as we can see in the metopes of the Athenian Treasury at Delphi. Pausanias (10.11.5-6) states that the treasury was built with the spoils of the victory over the Persians in the Battle of Marathon in 490 все (see Figure 7.14, page 170), giving us a terminus post quem for the beginning of the construction. There is indeed a base on the south side of the treasury for the display of battle trophies, but there has been debate over the years as to whether the base was added to a preexisting treasury or not. Recent archaeological analysis of the foundations favors the idea that base and treasury were built at the same time, and so the sculpture would date shortly after 490.

The sculptural program was dedicated to Herakles, the paramount Panhellenic hero, and Theseus, the hero of Athens. The deeds of Herakles were placed on the west and north sides, away from the main lines of sight on the Sacred Way, while the deeds of Theseus were placed in the nine south metopes facing the switchback of the Sacred Way, and his fight against the Amazons filled the six eastern metopes over the building’s entrance. The deeds of Theseus are in two groups: the first four show him fighting with brigands who plagued the road from Troizen, his home town, to Athens, where he came to claim his inheritance as the son of king Aigeus. The middle metope shows him being greeted by Athena on his arrival in Athens. The last four show later scenes, including the fight with the Minotaur and with an Amazon on the last metope (Figure 8.7). Thus, as the viewer walks along the Sacred Way, the metopes show an unfolding heroic biography.

Although fragmentary, one can readily see that the figures are in far more complicated poses than on the nearby, earlier Siphnian Treasury. As can be seen in the metope with Theseus and the Amazon, both figures twist and move in space, and rather than a combination of profile and frontal views, there is use of a three-quarter view. This is more of an artistic challenge, in that a body at an oblique angle is not symmetrical like the frontal Athena at Selinus/Selinunte. It diminishes in scale

as it recedes from the viewer, making a more lifelike pose. The more active figures show the asymmetry and bulging of muscles that vigorous poses create. The term rhythmos, which means pattern of movement or the combination and sequence of small actions required to carry out an action, describes this interest in how bodies move and work. The wrestling figures of the first metope are a good example, as Theseus wraps his arm around the waist of Kerkyon, who is in an unstable pose and will be thrown down by Theseus.

Rather than the impassive faces of many archaic figures, the face of Skiron in the second metope is distorted by the pain caused by Theseus, who jerks his head in the opposite direction in which his body is twisting.

Rather than the impassive faces of many archaic figures, the face of Skiron in the second metope is distorted by the pain caused by Theseus, who jerks his head in the opposite direction in which his body is twisting.

This interest in rhythmos can also be seen in other late archaic reliefs, such as the so-called ball player base (Figure 8.8). This work, found in a defensive wall built by Themistokles in 478 after the Persian destruction of Athens, was originally a base for a statue in the Kerameikos cemetery (this reuse gives us a terminus ante quem for the work, which is usually dated to 510-500 все). The range of poses and movements shows strong interest in how the body works in various actions, even though the ability to show three-quarter views and foreshortening is less convincing than on the treasury. As we will see later in this chapter, this interest in rhythmos is also found

|

in contemporary Athenian painted pottery, especially in the new red-figure technique. Indeed, the similarities of the ball player base to the Euphronios krater (see Figure 8.26, page 206) and to the metopes provide one reason that a date around 510-500 все was initially proposed for the metopes of the Athenian Treasury, in spite of the testimony about the Marathon dedication. Perhaps the Theseus metopes appear stiff when compared with some other works after 490, but the Athenian Treasury metopes are good examples of the developments in rendering the human figure at the end of the archaic period.

free-standing sculpture

There are two dominant types of free-standing sculpture in the sixth century, which have been given the general terms of kouros and kore, both of which have their origins in the seventh century. The kouros follows a formula of a standing, nude, beardless male, generally youthful in age, with long braided hair. Like one of the earliest surviving versions in marble, the monumental kouros from Cape Sounion (see Figure 6.4, page 135), the pose has the left leg forward and the arms held at the sides, with the stone between the middle of the arm and body removed. The major divisions of the body, such as the pelvis, knees, pectoral region, and collar bone, are articulated by strong ridges, while other details such as the abdominal muscles are shallow surface grooves. The hair, ears, and even the eyes are abstracted, geometric designs. The figure is conceived more as an assemblage of parts and combination of front, back, and side views, rather than as an organic body.

The earliest kouroi, as well as korai, are associated with sanctuaries, and early interpretations of the kouroi were that they represented Apollo. There are, however, no attributes identifying them as Apollo and they are found in sanctuaries of other gods and goddesses. By the early sixth century they

also serve as grave markers. There are also examples that are clothed or carry an animal like a ram or calf over the shoulders as an offering, but that otherwise share many of the stylistic features and formulas of nude statue. The use of the term kouros may imply a stronger precision and identity of subject matter than is actually the case. As we have seen, the standing male nude has a long tradition in Greek art going back to the Geometric period, and perhaps we should think of the appeal and success of the formula of the standing male nude as the result of its universality, idealism, and variability. The type could represent a god, a hero, or a mortal who had achieved fame or virtue; it could be used as a commemorative funerary monument or a votive offering. Its context and/or inscription would provide the cues for its specific purpose and identity.

also serve as grave markers. There are also examples that are clothed or carry an animal like a ram or calf over the shoulders as an offering, but that otherwise share many of the stylistic features and formulas of nude statue. The use of the term kouros may imply a stronger precision and identity of subject matter than is actually the case. As we have seen, the standing male nude has a long tradition in Greek art going back to the Geometric period, and perhaps we should think of the appeal and success of the formula of the standing male nude as the result of its universality, idealism, and variability. The type could represent a god, a hero, or a mortal who had achieved fame or virtue; it could be used as a commemorative funerary monument or a votive offering. Its context and/or inscription would provide the cues for its specific purpose and identity.

While following a formula, kouroi do vary widely in their appearance, both by time and by region. Two kouroi found at Delphi are dated around 570 bce, not long after the Sounion kouros (Figure 8.9). They are made of marble from Naxos, but are products of an Argolid sculptor, part of whose name, [-]medes, survives on the plinth (Palagia and Herz 2002, 243). These figures are more muscular in their proportions and their heads are less elongated than the Sounion kouros. While not completely “Daedalic,” they look back to that earlier style of the seventh century. They also offer a variation on the typical kouros, in that they wear boots rather than being barefoot and there is a suggestion of an armor breastplate on their chests. What is interesting about these statues is that Herodotos mentions two statues at Delphi in a story told by Solon about blessings for men. The mother of Kleobis and Biton had to go to the feast at the Heraion in Argos; with the farm animals unavailable to pull her wagon, her sons pulled it themselves for 45 stade (about 8.3 km). After receiving much praise on their arrival, their mother asked the goddess to “give them whatsoever is best for a man to

win.” Accordingly, they died in their sleep while resting at the sanctuary, renowned as forever youthful and pious. According to Herodotos, “The Argives made statues of them and dedicated them at Delphi, as of two men who were the best of all” (1.31, tr. Grene, 46).

By dedicating them at Delphi, the Argives promoted their own excellence in a Panhellenic context, much as victor statues did at Olympia. While not true portraits, they commemorate the two brothers as ideal men.

By dedicating them at Delphi, the Argives promoted their own excellence in a Panhellenic context, much as victor statues did at Olympia. While not true portraits, they commemorate the two brothers as ideal men.

There has been some debate as to whether the kouroi are indeed Kleobis and Biton, and an alternative identification based on a new reading of the inscription suggests that they might instead be the mythological Dioskouroi, the twin brothers of Helen (Faure 1985).

Whether or not this theory is eventually accepted, it points out that the formula of the nude male could serve a variety of purposes; without more evidence, either reading is plausible and the key to the specific meaning depends upon inscription and context.

A slightly later kouros has much more slender proportions and demonstrates less interest in the articulation of the body parts and musculature (Figure 8.10). This is more typical of Ionian kouroi, made in the eastern Greek islands. This particular statue was found in the cemetery at Megara Hyblaea, north of Syracuse/Siracusa, Sicily. Marble was rare in Sicily and limestone was the predominant material for architectural sculpture, so this is likely an import.

When set up as a grave marker, an inscription was

carved on its leg: “[tomb] of Sombrotidas, the physician, [son of] Mandrokles.” Sombrotidas may have been an Ionian immigrant, as inscriptions on a statue leg are an Ionian tradition. As a practicing physician, however, Sombrotidas would not have been young when he died. His prominence derives from his profession, but the kouros gives him the appropriate visual symbol of male excellence. It is likely that the expense of the statue was covered by the family of Sombrotidas, and as we shall see in Chapter 11, a nearly life-size and imported statue would have been a significant financial undertaking for the family. The personal importance and social value of commemoration and offerings are clearly signaled by works like this.

This was also the case for the statue associated with the grave of Kroisos discussed in Chapter 5 (see Figure 5.24, page 123). As the inscription found near that statue indicates, Kroisos was killed in battle: “Stay and mourn at the monument for dead Kroisos whom violent Ares destroyed, fighting in the front rank” (tr. Boardman 1991, 104). Although he might have been relatively young when he died, he is not remembered visually as a warrior, but as an ideal youth. Whether or not this statue belongs to the base, we see the same formula as in other kouroi. The surface of the figure has become more complex and subtle in the articulation of the muscles, bones, and body divisions, while the figure is becoming more rounded and three-dimensional in concept. The structure of the face is more complex, and the eyes bulge outward from the eye socket less than earlier kouroi.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-29; просмотров: 1910;

8.2 West frieze from the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, c. 530-525 все. 253/i6 in (64 cm). Delphi Museum. Abduction scene? Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

8.2 West frieze from the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, c. 530-525 все. 253/i6 in (64 cm). Delphi Museum. Abduction scene? Photo: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.