Treatment of acute cholecystitis

For acute cholecystitis, initial treatment is conservative:

– local abdominal hypothermia;

– bowel rest;

– intravenous hydration;

– analgesia with NSAID;

– spasmolytical therapy;

– intravenous antibiotics.

Although not initially an infective process, broad-spectrum antibiotics are used and should be guided by local microbiological policy to target the most common organisms found in the biliary tract. These include Escherichia coli, klebsiella, enterobacter and enterococcus species. Anaerobes are less significant but include clostridium and bacteroides species.

Following successful conservative treatment most patients are discharged from hospital for future elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If acute cholecystitis resolves, laparoscopic cholecystectomy may be carried out 4–6 weeks later. Delayed surgery carries the risk of recurrent biliary complications.

For frail and elderly patients who have only a signle attack, or mild recurrent episodes, conservative management may be the mainstay of treatment.

Indications for urgent operation are:

– peritonitis;

– inefficacy of conservative treatment during 24–48 hours (retention of abdominal pain and muscles resistance, increasing of body temperature and polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, signs of peritonitis, jaundice).

In cases of severe inflammation, shock, or if the patient has higher risk for general anaesthesia (required for cholecystectomy), the managing physician may elect to have an interventional radiologist insert a percutaneous drainage catheter into the gallbladder (“percutaneous cholecystostomy tube”) and treat the patient with antibiotics until the acute inflammation resolves. The patient may later warrant cholecystectomy if their condition improves.

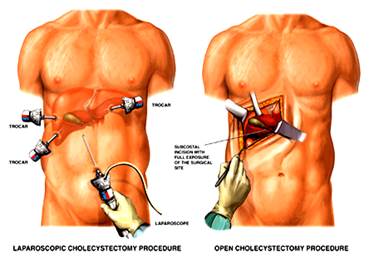

Gallbladder removal, cholecystectomy, can be accomplished via open surgery or a laparoscopic procedure. Laparoscopic procedures can have less morbidity and a shorter recovery stay. Open procedures are usually carried out if complications have developed or the patient has had prior surgery to the region, making laparoscopic surgery technically difficult. A laparoscopic procedure may also be “converted” to an open procedure during the operation if the surgeon feels that further attempts at laparoscopic removal might harm the patient. Open procedure may also be carried out if the surgeon does not know how to perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Preparation of patients undergoing cholecystectomy is similar for both urgent open and laparoscopic procedures.

Surgical incisions for open cholecystectomy are: line oblique incision in right subcostal region (is rarely performed because of the tendency for herniation); upper middle line laparotomy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed using 4 considerably smaller incisions (fig. 11).

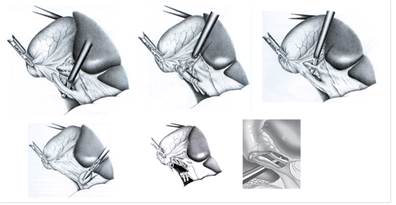

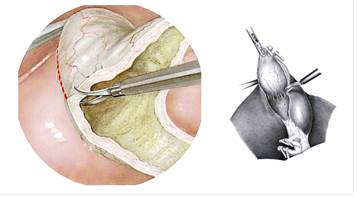

The phases of operation are: visual inspection of abdominal cavity and operative confirmation of diagnosis; puncture of gallbladder if it is distending; dissection and visualization of Kalo’s trigonum structures; cutting of cystic duct and artery with ligation or clipping (fig. 12); removing of gallbladder (fig. 13); control of bleeding and bile leak; sanation and drainage of abdominal cavity.

Figure 11 – Open and laparoscopic procedures

Figure 12 – Dissection of Kalo’s trigonum structures

Figure 13 – Removing of gallbladder

Complications of cholecystectomy:

– bile leak (“biloma”);

– bile duct injury (about 5–7 out of 1000 operations. Open and laparoscopic surgeries have essentially equal rate of injuries, but the recent trend is towards fewer injuries with laparoscopy. It may be that the open cases often result because the gallbladder is too difficult or risky to remove with laparoscopy);

– abscess;

– wound infection;

– bleeding (liver surface and cystic artery are most common sites);

– hernia;

– organ injury (intestine and liver are at highest risk, especially if the gallbladder has become adherent/scarred to other organs due to inflammation (e.g. transverse colon);

– deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism (risk can be decreased through use of sequential compression devices on legs during surgery);

– fatty acid and fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption.

Postoperative treatment

Administer intravenous antibiotics postoperatively. The length of administration is based on the operative findings and the recovery of the patient.

Antiemetics and analgesics are administered to patients experiencing nausea and wound pain.

A liquid diet may be started when bowel function returns.

Follow-up care

After hospital discharge, patients must have a light diet and limit their physical activity for a period of 4 weeks – 3 months based on the surgical approach (i.e., laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy). The patient should be evaluated by the surgeon in the clinic to determine improvement and to detect any possible complications.

Following cholecystectomy, about 5–10% of patients develop chronic diarrhoea. This is usually attributed to bile salts. The frequency of enterohepatic circulation of bile salts increases after the gallbladder is removed, resulting in more bile salt reaching the colon. In the colon, bile salts stimulate mucosal secretion of salt and water.

Postcholecystectomy diarrhoea usually is mild and can be managed with occasional use of over-the-counter antidiarrhoeal agents. More frequent diarrhoea can be treated with daily administration of a bile acid binding resin.

Following cholecystectomy, a few individuals experience recurrent pain resembling biliary colic. The term “postcholecystectomy syndrome” is sometimes used for this condition.

Many patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome have long-term functional pain that was originally misdiagnosed as being of biliary origin. Diagnostic and therapeutic efforts should be directed at the true cause.

Some individuals with postcholecystectomy syndrome have an underlying motility disorder of Oddi’s sphincter, termed biliary dyskinesia, in which the sphincter fails to relax normally following ingestion of a meal. The diagnosis can be established in specialized centers by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Prognosis

For uncomplicated cholecystitis, the prognosis is excellent, with a very low mortality rate. In patients who are critically ill with cholecystitis, the mortality rate approaches 50–60%, especially in the setting of peritonitis.

Дата добавления: 2015-07-04; просмотров: 2304;