Guns That Roll: Mobile Artillery

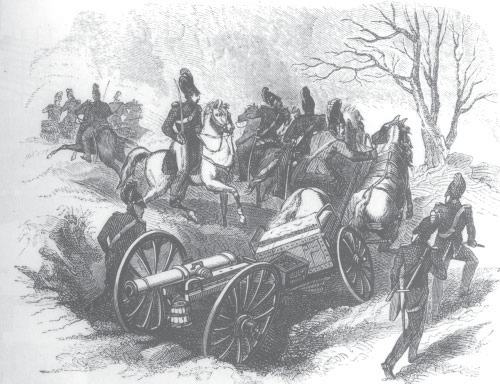

Moving a field piece into position.

Artillery, as we have seen, revolutionized siege warfare. The early siege guns, though, were far from ideal. They were so heavy that moving one of them was a major engineering project. Barrels were weak, especially those of bombards built of welded iron rods and hoops, so they couldn’t contain much pressure. Consequently their projectiles had low velocity. For lobbing one big stone ball after another at the same spot on a wall they were fine, but the rulers of France and Burgundy wanted more. Especially, they wanted more mobility.

The French and Burgundians engaged in an arms race beginning during the latter part of the Hundred Years War. The English, although they had introduced guns to that war at Crecy, didn’t bother to compete. They were convinced that their longbow was the master weapon. They were to regret that idea.

The new guns were all cast in bronze and could handle much higher pressures than the old bombards. Their barrels were much longer in proportion to the size of their projectiles. This not only increased accuracy, it gave the exploding powder more time to push the projectile, increasing the velocity. The wrought iron cannon balls were smaller than the stones shot from the bombards, but they were heavier in proportion to their size and much harder and tougher. They wouldn’t shatter on a stone wall as stone shot often did. The new guns were cast with lugs, called “trunnions,” on their barrels near the center of gravity. The guns swivelled on the trunnions so they could be elevated to hit targets at varying ranges. Most important, the guns were mounted on wheeled carriages so they could be easily moved.

The new French cannons brought an end to the Hundred Years War. The French were able to quickly concentrate their cannons against castles the English held, knock their walls down, and move to the next stronghold. But a couple of small engagements demonstrated that the French had a most potent field weapon as well as a wall‑batterer.

At Formigny in 1450, French and English forces of equal size met. The English reaction was almost reflexive. Most of the knights dismounted and formed a wall of lance points. The infantry archers stepped forward, planted sharpened stakes to stop a cavalry charge, and strung their bows. All waited for the traditional French cavalry charge.

The French didn’t charge. They just hauled up their cannons and blasted the English away. At Castillon, three years later, an English army attacked a French force that was besieging an English stronghold. This time, the English were the attackers. The French had no longbows, but they had cannons. And they proved that cannons were as effective on the defensive as they were on the offensive. The English commander, John Talbot, was killed, and the Hundred Years War effectively ended soon afterwards. Later, mobile artillery was to prove its worth in another theater.

In 1494, Charles VIII of France took his artillery into Italy to enforce his claim to Naples. The result was a sort of 15th century Blitzkrieg. Cities and fortresses surrendered to the French as soon as they saw the French artillery.

There was some resistance in Naples. The fortress of Monte San Giovanni, which had previously withstood a siege of seven years, was taken in eight hours, after which the French troops massacred the garrison. Charles took Naples and then returned to France.

His success, however, inspired an alliance of Spain, Venice, the Papal States, and Milan. The Italian Wars, what some historians consider Europe’s first “world war,” had begun. Before they were over, all the major European powers except England, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire would be sucked into the Italian battlefield. The principal combatants were the strangely named Holy Roman Empire of the German People – which, under Emperor Charles V, included the rich and powerful kingdom of Spain – and the kingdom of France. The perpetu‑ally quarreling Italian mini‑states allied themselves with one or another of the great powers. The Swiss cantons supplied troops to both the French and the Imperialists. Infantrymen were, in fact, the main cash crop of Switzerland. Because they had defeated the armies of both Burgundy and the Empire, the Swiss infantry had become the terror of Central Europe. The Swiss cantons rented out their soldiers to the princes of Europe. The Swiss fought in a dense phalanx – mostly pikemen supported by halberdiers, crossbow archers, and men swinging six‑foot‑long two‑handed swords. The Swiss phalanx was quickly copied by the infantry of all the continental powers. The Swiss soldiers considered fighting in these many wars their patriotic duty. They brought money to their home cantons. Their motives were not pure patriotism, however. The loot from enemy camps and cities was a powerful inducement, as was their hatred for the Holy Roman Empire (the Swiss heroes, Arnold von Winkler and William Tell, had resisted the Empire).

Usually, the Swiss fought on the side of the French. In 1513, however, the Imperialists outbid the French, and the Schweizer footmen marched with the forces of the Empire to break the siege of Novaro, where a Swiss garrison was holding out against the French. French artillery broke down the walls of Novaro, but the Swiss erected barricades behind the breaches. Then the relieving army swept down on the French, captured 22 French guns and killed all the gunners.

They lost only 400 men in their attack. Two years later, at Maringano, the Swiss didn’t do so well. This time, they did not attack the rear of a besieging army, but charged directly at the front of a heavily fortified French army equipped with 72 field guns. The Swiss did capture part of the French works but had to dig in under heavy fire. The next day, they were forced back by fire from the artillery and the French harquebusiers. Then the French cavalry turned their retreat into a rout. The attack at Marignano was the last time the Swiss fought French troops and their artillery before the Swiss Guard was wiped out in the French Revolution.

In 1522, the Swiss were again on the side of the French. Prospero Colonna, a condottiere in the service of the Empire, was besieging Milan. The Swiss were eager to attack. As at Novaro, they would come in behind a besieging army, and their enemy was the hated Imperialists. The French commander, Lautrec, was not so optimistic. It looked as if Colonna had fortified the rear of his army as well as the part facing the city. But the Swiss were so insistent, Lautrec was afraid they’d mutiny if he didn’t let them attack. So on April 27, 1522, he ordered the attack.

Colonna had placed cannons and Spanish arquebusiers and musketeers behind a breastwork that overlooked a sunken road. The Imperial cannons blasted bloody lanes through the Swiss phalanx. A single shot striking that dense mass of humanity could kill up to 30 men. A thousand Swiss were killed before they even reached the sunken road. When the Swiss reached the ditch and leaped into it, four lines of Spanish handgunners firing successive volleys shot them down. A few Swiss climbed over the bodies of their comrades to reach the top of the breastwork, but Imperial pikemen pushed them back. More than 3,000

Swiss were killed. The survivors fled, and, as historian Christopher Duffy puts it, “The bellicose and independent spirit of the Swiss was broken forever.”

Field artillery was improved continuously, well into the 19th century. It became one of the three key elements of warfare and was the key to Napoleon’s victories. For a time, its supremacy was challenged by the high‑velocity rifle, but then cannons were given rifling and recoil‑absorbing mechanisms, and in World War II, it was still the most lethal of military weapons.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1196;