Seizing the Seas: The Sailing Man of War

National Archives from U.S. Bureau of ships

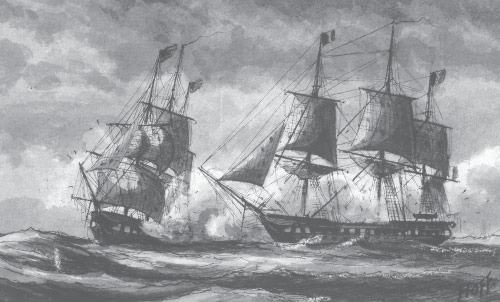

U.S. frigate Constellation battles the French frigate L’Insurgente in 1799.

The time had come to put an end to the Frankish meddling in the trade with the East. The two great powers of western Islam, Turkey and Egypt, had put aside their rivalries to send a combined fleet of 200 galleys to the Indian Ocean. Each of the galleys had three cannons positioned to fire over its bow, and the fleet carried 15,000 soldiers for boarding the ships of the infidels. The admiral, Emir Husain Kurdi, had spent two years looking for the main Frankish fleet, but at last the warriors of Islam were about to meet the interlopers.

The “Franks” (actually Portuguese, but in 1509, all European Christians were Franks to the Muslims) had sent their ships around Africa and were trading with India. Trade with the East had long been a Muslim monopoly. Over‑land trade consisted of caravans of Turkish Muslims passing through the Muslim lands of central Asia. Goods that got to Europe this way were extremely expensive, because each local ruler levied a tax on the caravans. Transportation by sea was less expensive. The Arabs of Arabia and the east coast of Africa had pioneered the sea routes centuries before the birth of Mohammed. Europeans had lost the Crusades, but had gained a thirst for the goods of the East. Merchandise from India, Persia, the Indies, and China traveled in Muslim bottoms and brought enormous wealth to the rulers of Dar es Islam (the Land of Islam), especially the Sultan of Egypt. The Egyptians shipped these Eastern luxuries to Europe through Venice, and that Italian city‑state became a mighty power in the Mediterranean. That’s one of the reasons why Venice’s ally, the Sultan of Egypt, and its enemy, the Sultan of Turkey, seldom saw eye‑to‑eye.

This project was an exception. Portuguese capture of the trade with the East would hurt not only Egypt and Venice, but Turkey. The Ottoman Empire controlled much of the land traversed by the caravans. If the spices, gold, silk, and other goods from the East were available from Christian merchants and much lower prices, the Europeans could be expected to ignore the caravan‑carried goods entirely.

That day, the Muslim fleet, stationed in the Indian port of Diu, heard that the Portuguese fleet was approaching. The Christians had only 17 ships, so the Muslim sailors rowed confidently out to meet them.

But the Christian ships were all larger than the Muslim galleys. More important, they were a different type of ship entirely, the product of centuries of development, most of which had escaped the notice of the Muslims.

Trade between the countries of western Europe was to a very large extent waterborne. It followed the many navigable rivers; crossed inland seas like the Mediterranean and the Baltic, much rougher seas such as the North Sea and even went into the ferocious Atlantic. Commerce in the Dar es Islam was different. In the arid lands that made up the bulk of Islamic territory, trade mostly happened by caravan. Trade was done by boat in the islands of the East Indies, but most of that was short‑range island‑hopping. The long distance trade between India, Africa, and Arabia depended on trade winds. For half of the year the winds blew west, for the other half, east. The Arabs had developed a specialized kind of ship, the dhow, to take advantage of that environment. For centuries, warships of the Mediterranean powers, both Muslim and Christian, had been almost identical – versions of the galley. (See Chapter 4.) Galleys were almost useless for commerce and were totally useless for long‑distance trading. Most of a galley was taken up by rowers, and rowers need food and water. So galleys had to make frequent stops to replenish their supplies and had no room for merchandise. For trade, the Europeans developed “round ships,”

ships much wider in relation to their length than galleys. They had no oars and no rowers, so they could hold more cargo. To move these vessels in the variable winds of the northern seas, the European sailors developed sails that let them proceed against the wind. Weather was a problem for European sailors, especially those in northern waters. The round ships had high sides, unlike galleys, which had to be low to accommodate the oars (a necessity in rough water), and they were heavily built, unlike galleys, which had to be light so the rowers could move them rapidly.

Pirates were another problem. In the late 13th and 14th centuries, new types of ships were developed. They were slimmer than the old round ships and much faster, but they were still strongly built and still capable of carrying a decent amount of cargo. They had high “castles” for and aft, where crossbowmen could be stationed. They also had crows’ nests on their masts where more crosssbowmen could stand ready to shoot any pirates. When cannons were invented, ship owners mounted them on their vessels. At first they were placed on the castles, but the weight of the guns made the ships unstable. At the beginning of the 16th century, ship builders began cutting gun ports in the hulls.

With these sturdy, all‑weather ships, able to sail against the wind and stay at sea for months without touching land, the Portuguese began working their way around Africa. England and France were immersed in the Hundred Years War, and Spain was still trying to drive the Muslims back to Africa. The Portuguese had already driven the Muslims out of their country, and they were able to look for a new route to the East.

The Turks and Egyptians saw sails and tried to form a line to attack the infidels. Forming a line wasn’t easy on the lively Indian Ocean. Galleys were much better adapted to inland seas such as the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.

The galleys’ guns were loaded and their gunners ready. The musketeers made sure their matches were lighted, and the archers had nocked their arrows.

The Portuguese ships suddenly turned, presenting their sides to the advancing galleys. Then the broadsides began. The Portuguese cannons were heavier and outranged those of the Muslims. And the 17 Portuguese ships had more guns than the 200 Muslim galleys. Cannon balls ploughed through rows of rowers, leaving masses of gore, gory bodies and body parts. They smashed the hulls of the fragile galleys. It was more of a massacre than a battle. Shanbal, a contemporary Arab historian, gave an account of the battle that shows that the tendency to minimize your side’s losses and exaggerate the enemy’s is, by no means, modern:

Many on the Frankish side were slain, but eventually the Franks prevailed over the Muslims, and there befell a great slaughter of the Emir Husain’s soldiers, about 600 men, while the survivors fled to Diu. Nor did he [the Frank] depart until they had paid him much money.

Actually, the Muslim fleet was practically annihilated. The few surviving galleys ran themselves ashore and their crews fled toward Diu. Very few Portuguese were killed. The Muslims tried three more times to drive the Portuguese from the coast of Africa and India. Each time, it was galleys versus sailing ships. And each battle was a replay of Diu.

The introduction of the sailing warship changed warfare and changed the world. The galley suddenly became obsolete. Sailing ships that could travel to the far ends of the world and still outfight galleys replaced all oar‑driven warships. There was one more big galley battle in the Mediterranean, at Lepanto, a couple of generations after Diu, but even there, Don Juan of Austria, the Christian admiral, used galleasses – big, heavily gunned ships – to break up the Turkish formation before the galleys clashed. The loss of the trade with the East began to weaken the Muslims, and the first Muslim casualty was Egypt. The Turks conquered the weakened sultanate on the Nile eight years after Diu.

Portugal thrived on the trade with the East. One of its India‑bound ships made a navigational error and discovered Brazil, but before that a Genoese sailor convinced the king and queen of Spain that he could get to the Far East quicker by sailing west; Columbus made a mistake, but he discovered a whole new world.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1131;