Power in the Hands: The Matchlock

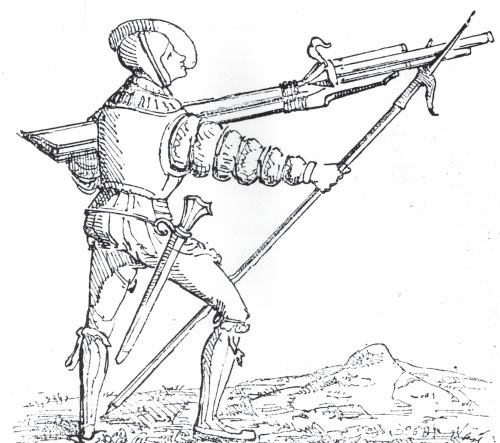

Soldier firing a matchlock musket.

The first gun small enough to be carried by infantry was far from a decisive weapon. A typical “hand cannon” was a short metal tube fitted to the end of a wooden pole. From a distance, it looked like a short spear. The hand gunner loaded his weapon with gunpowder and a lead ball. He then held the wooden pole with one hand, and with the other he poked a red‑hot iron wire into a hole, called a “touch‑hole” in the top of the gun. Guiding the wire to the touch‑hole meant that he was not able to aim. The gun made a bright flash, a terrifying noise, and a lot of smoke. Other than that, it seldom did any damage. There was a good reason why the Arabs and Turks were not interested in guns.

Jump ahead about three centuries: Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer, is asked by some Indians he is visiting (members of the Huron tribe), for help against their enemies, members of the formidable Iroquois confed‑eracy. Champlain loads his gun, a long heavy device that bears no resemblance to the early hand cannons, with a charge of powder and three bullets. He joins the army of his new friends, and they confront the Iroquois army. Both armies consist of naked warriors armed with bows and arrows. Two of the Iroquois chiefs advance to challenge the Hurons. One of the chiefs lifts his bow.

Champlain fires.

Both chiefs fall to the ground. The Iroquois flee.

Champlain’s shot, hitting two enemies at once, was probably the best the explorer ever made. It was also one of the most historic in North American history. It started the centuries‑long hostility between the Iroquois and the French, a development that had the most profound effect on colonial North America.

A lot of development went into Champlain’s exceptionally lethal weapon.

One of the first was getting rid of the hot wire as a means of ignition. Using wires to fire guns meant that soldiers had to have a fire nearby to keep their wires hot. That was not very convenient in the midst of a battle. Somebody substituted a piece of cord that had been steeped in potassium nitrate and brandy to make it burn slowly and steadily. Its effect was something like the punk used to ignite Fourth of July fireworks. Some fires were still needed in case a match went out, but usually a soldier could reignite his match from another soldier’s.

A burning match could not be easily poked into a touch‑hole, so gunmakers built guns with a small pan above the touch‑hole. When gunpowder in this “priming pan” ignited, the fire would flash into the main charge.

The gun, though, was still no easier to aim. Then some genius built a gun with a pivoted arm that would swing the burning end of the match right into the pan. The arm was fastened to the wooden stock, so the pan and the touch‑hole were moved to the side of the gun. That made construction of the swivel simpler, but, more important, it made aiming the gun easier – the swivel didn’t interfere with the line of sight.

While these improvements had been going on, guns got longer and heavier.

Their long barrels could propel a bullet with enough force to be deadly at a distance. Fitting a trigger to let the gunner move the swiveled arm with one finger made aiming still easier. Gunsmiths used a variety of trigger arrangements. The simplest was extending the swiveling arm below the pivot so the gunner could lower the match by pulling the bottom of the arm. That made an awkward reach for the trigger finger, and it required the touch‑hole to be too far forward for efficiency. More efficient was the system that put the trigger at the center of the bottom of the stock and had it move the match‑holder with an arrangement of levers. A spring returned the match‑holder, or “serpentine,” to its original position when the gunner released the trigger. It finally became easy to aim and fire a gun – as easy as aiming and shooting a crossbow. To further aid the process, gunsmiths began fitting sights to their products.

The Portuguese brought this more efficient gun to India, and Indian gunmakers were still building this type of weapon well into the 19th century.

Another, somewhat later development of the matchlock caught on in Japan, where, again, the Portuguese introduced it. This was the “snapping matchlock.”

The gunner cocked the serpentine as if he were firing a single‑action revolver.

When he squeezed the trigger, the serpentine brought the match into the pan with a snap, propelled by a spring. That made it possible for a gunner to fire the instant he lined up his gun on the target. The Japanese were still using this type of gun when Commodore Perry arrived. The snapping matchlock later went out of fashion in Europe because the serpentine sometimes snapped the match into the priming pan hard enough to put the match out.

European gunsmiths continued to improve what had now become the most important weapon on the battlefield. Barrels with spiral rifling appeared. Spinning the bullet gave it far more accuracy: A shot was effective at much longer ranges. These early rifles were difficult to load, however. The bullet had to be bigger than the bore so the rifling would cut into it and make it spin when fired.

That meant the bullet had to be pounded down the barrel. And the rather crude gunpowder of the time clogged up the rifling after a few shots making the gun impossible to load until the bore was cleaned. Some wealthy hunters bought rifles, but soldiers continued to use smoothbores. Loading a matchlock was slow enough, even without the need to pound a bullet down the barrel and clean it after every three or four shots. For safety, a soldier had to take the match off his gun before loading, hold it at a safe distance while he poured loose powder down the barrel, rammd a bullet and wad on top of that, and put more powder in the priming pan.

He then put the match back on the serpentine, blew on it to expose the burning coal, and aimed it at the target. Prince Maurice of Nassau, a 17th‑century Dutch general, prescribed 43 separate movements for his musketeers’ drill.

Musketeers used muskets – the latest development of the matchlock. A musket was exactly the same as the earlier and lighter arquebus, but it was bigger. It was so heavy the musketeer had to fire it from a rest – a long forked stick or metal rod. The advantage of the musket was that its heavy bullet would penetrate armor at 200 yards. One marksman wasn’t likely to hit an individual enemy at 200 yards with a smoothbore musket, but infantry and cavalry in those days fought in dense masses that made large targets. A volley of musket balls would have a devastating effect on charging heavy cavalry or armored pikemen.

The matchlock quickly replaced the crossbow in continental armies, largely because it penetrated armor better. It didn’t make armor disappear, but it required soldiers to wear ever‑heavier armor. By the time the musket appeared, most soldiers had stopped wearing most armor. Eventually, infantry wore little more than a helmet and the heaviest cavalry wore only metal cuirasses. Although for centuries, the English had an almost religious belief in the supremacy of the longbow over all other hand weapons, in the early 16th century, the gun replaced the longbow in England. As guns got better and better, armies included higher and higher proportions of arquebusiers and musketeers to other troops.

The use of muskets on a large scale required more complicated and rigor‑ous training for infantry. Just to use their slow‑loading weapons efficiently, soldiers had to be drilled until they could perform processes like Prince Maurice’s 43 motions almost subconsciously. Masses of musketeers had to be drilled so they could perform the loading and firing motions simultaneously, because generals had found that volleys had a greater shock effect on enemies than individual fire. The drilling of musketeers and arquebusiers had to be done with pikemen because they had to be protected from cavalry by pikemen while they were reloading. The musketeers had to learn how to move into or behind pike formations while loading and how to suddenly reappear and fire volleys when their pieces were loaded.

Warfare had become a lot more complicated. No longer could a country such as England field a highly effective militia whose main training was shooting arrows every Sunday afternoon. Even guard duty had become complex. Here’s what Virginia had to say about sentinels:

…he shall shoulder his piece, both ends of his match being alight, and his piece charged, and primed, and bullets in his mouth, there to stand with a careful and waking eye, untill such time as his Corporall shall relieve him.

To speed reloading, soldiers literally spit bullets into the gun. The idea was to enable the sentry to fire quickly if a number of enemies suddenly appeared.

But holding two or three bullets in his mouth probably also helped him keep “a careful and waking eye.”

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1534;