CRIMES OF ANATOMY

Body Snatching and Other Sordid Tales from the Dawn of Human Dissection

Enough years have passed since the use of Pachelbel’s Canon in a fabric softener commercial that the music again sounds pure and sweetly sad to me. It’s a good choice for a memorial service, a classic and effective choice, for the men and women gathered (here today) have fallen silent and somber with the music’s start.

Noticeably absent amid the flowers and candles is the casket displaying the deceased. This would have been logistically challenging, as all twenty‑some corpses have been reduced to neatly sawed segments–hemisections of pelvis and bisected heads, the secret turnings of their sinus cavities revealed like Ant Farm tunnels. This is a memorial service for the unnamed cadavers of the University of California, San Francisco, Medical School Class of 2004 gross anatomy lab. An open‑casket ceremony would not have been especially horrifying for the guests here today, for they have not only seen the deceased in their many and various pieces, but have handled them and are in fact the reason they have been dismembered. They are the anatomy lab students.

This is no token ceremony. It is a sincere and voluntarily attended event, lasting nearly three hours and featuring thirteen student tributes, including an a capella rendition of Green Day’s “Time of Your Life,” the reading of an uncharacteristically downbeat Beatrix Potter tale about a dying badger, and a folk ballad about a woman named Daisy who is reincarnated as a medical student whose gross anatomy cadaver turns out to be himself in a former life, i.e., Daisy. One young woman’s tribute describes unwrapping her cadaver’s hands and being brought up short by the realization that the nails were painted pink. “The pictures in the anatomy atlas did not show nail polish,” she wrote. “Did you choose the color?… Did you think that I would see it?… I wanted to tell you about the inside of your hands… I want you to know you are always there when I see patients. When I palpate an abdomen, yours are the organs I imagine. When I listen to a heart, I recall holding your heart.” It is one of the most touching pieces of writing I’ve ever heard. Others must feel the same; there isn’t an anhydrous lacrimal gland in the house.

Medical schools have gone out of their way in the past decade to foster a respectful attitude toward gross anatomy lab cadavers. UCSF is one of many medical schools that hold memorial services for willed bodies.

Some also invite the cadavers’ families to attend. At UCSF, gross anatomy students must attend a pre‑course workshop hosted by students from the prior year, who talk about what it was like to work with the dead and how it made them feel. The respect and gratitude message is liberally imparted. From what I’ve heard, it would be quite difficult, in good conscience, to attend one of these workshops and then proceed to stick a cigarette in your cadaver’s mouth or jump rope with his intestines.

Hugh Patterson, anatomy professor and director of the university’s willed body program, invited me to spend an afternoon at the gross anatomy lab, and I can tell you here and now that either the students were exceptionally well rehearsed for my visit or the program is working.

With no prompting on my part, the students spoke of gratitude and preserving dignity, of having grown attached to their cadavers, of feeling bad about what they had to do to them. “I remember one of my teammates was just hacking him apart, digging something out,” one girl told me, “and I realized I was patting his arm, going, ‘It’s okay, it’s okay.’”

I asked a student named Matthew whether he would miss his cadaver when the course ended, and he replied that it was actually sad when “just part of him left.” (Halfway through the course, the legs are removed and incinerated to reduce the students’ exposure to the chemical preservatives.)

Many of the students gave their cadavers names. “Not like Beef Jerky. Real names,” said one student. He introduced me to Ben the cadaver, who, despite having by then been reduced to a head, lungs, and arms, retained an air of purpose and dignity. When a student moved Ben’s arm, it was picked up, not grabbed, and set down gently, as if Ben were merely sleeping. Matthew went so far as to write to the willed body program office asking for biographical information about his cadaver. “I wanted to personalize it,” he told me.

No one made jokes the afternoon I was there, or anyway not at the corpses’ expense. One woman confessed that her group had passed comment on the “extremely large genitalia” of their cadaver. (What she perhaps didn’t realize is that the embalming fluid pumped into the veins expands the body’s erectile tissues, with the result that male anatomy lab cadavers may be markedly better endowed in death than they were in life.) Even then, reverence, not mockery, colored the remark.

As one former anatomy instructor said to me, “No one’s taking heads home in buckets anymore.”

To understand the cautious respect for the dead that pervades the modern anatomy lab, it helps to understand the extreme lack of it that pervades the field’s history. Few sciences are as rooted in shame, infamy, and bad PR as human anatomy.

The troubles began in Alexandrian Egypt, circa 300 B.C. King Ptolemy I was the first leader to deem it a‑okay for medical types to cut open the dead for the purpose of figuring out how bodies work. In part this had to do with Egypt’s long tradition of mummification. Bodies are cut open and organs removed during the mummification process, so these were things the government and the populace were comfortable with. It also had to do with Ptolemy’s extracurricular fascination with dissection. Not only did the king issue a royal decree encouraging physicians to dissect executed criminals, but, come the day, he was over at the anatomy room with his knives and smock, slitting and probing alongside the pros.

Trouble’s name was Herophilus. Dubbed the Father of Anatomy, he was the first physician to dissect human bodies. While Herophilus was indeed a dedicated and tireless man of science, he seems to have lost his bearings somewhere along the way. Enthusiasm got the better of compassion and common sense, and the man took to dissecting live criminals . According to one of his accusers, Tertullian, Herophilus vivisected six hundred prisoners. To be fair, no eyewitness account or papyrus diary entries survive, and one wonders whether professional jealousy played a role.

After all, no one was calling Tertullian the Father of Anatomy.

The tradition of using executed criminals for dissections persisted and hit its stride in eighteenth‑ and nineteenth‑century Britain, when private anatomy schools for medical students began to flourish in the cities of England and Scotland. While the number of schools grew, the number of cadavers stayed roughly the same, and the anatomists faced a chronic shortage of material. Back then no one donated his body to science. The churchgoing masses believed in a literal, corporal rising from the grave, and dissection was thought of as pretty much spoiling your chances of resurrection: Who’s going to open the gates of heaven to some slob with his entrails all hanging out and dripping on the carpeting? From the sixteenth century up until the passage of the Anatomy Act, in 1836, the only cadavers legally available for dissection in Britain were those of executed murderers.

For this reason, anatomists came to occupy the same terrain, in the public’s mind, as executioners. Worse, even, for dissection was thought of, literally, as a punishment worse than death. Indeed, that–not the support and assistance of anatomists–was the authorities’ main intent in making the bodies available for dissection. With so many relatively minor offenses punishable by death, the legal bodies felt the need to tack on added horrors as deterrents against weightier crimes. If you stole a pig, you were hung. If you killed a man, you were hung and then dissected . (In the freshly minted United States of America, the punishable‑by‑dissection category was extended to include duelists, the death sentence clearly not posing much of a deterrent to the type of fellow who agrees to settle his differences by the dueling pistol.)

Double sentencing wasn’t a new idea, but rather the latest variation on the theme. Before that, a murderer might be hung and then drawn and quartered, wherein horses were tied to his limbs and spurred off in four directions, the resultant “quarters” being impaled on spikes and publicly displayed, as a colorful reminder to the citizenry of the ill‑advisedness of crime. Dissection as a sentencing option for murderers was mandated, in 1752 Britain, as an alternative to postmortem gibbeting. Gibbeting–though it hits the ear like a word for happy playground chatter or perhaps, at worst, the cleaning of small game birds– is in fact a ghastly verb. To gibbet is to dip a corpse in tar and suspend it in a flat iron cage (the gibbet) in plain view of townsfolk while it rots and gets pecked apart by crows. A stroll through the square must have been a whole different plate of tamales back then.

In attempting to cope with the shortage of cadavers legally available for dissection, instructors at British and early American anatomy schools backed themselves into some unsavory corners. They became known as the kind of guys to whom you could take your son’s amputated leg and sell it for beer money (37½ cents, to be exact; it happened in Rochester, New York, in 1831). But students weren’t going to pay tuition to learn arm and leg anatomy; the schools had to find whole cadavers or risk losing their students to the anatomy schools of Paris, where the unclaimed corpses of the poor who died at city hospitals could be used for dissection.

Extreme measures ensued. It was not unheard of for an anatomist to tote freshly deceased family members over to the dissecting chamber for a morning before dropping them off at the churchyard. Seventeenth‑century surgeon‑anatomist William Harvey, famous for discovering the human circulatory system, also deserves fame for being one of few medical men in history so dedicated to his calling that he could dissect his own father and sister.

Harvey did what he did because the alternatives–stealing the corpses of someone else’s loved ones or giving up his research– were unacceptable to him. Modern‑day medical students living under Taliban rule faced a similar dilemma, and, on occasion, have made similar choices. In a strict interpretation of Koranic edicts regarding the dignity of the human body, Taliban clerics forbid medical instructors to dissect cadavers or use skeletons– even those of non‑Muslims, a practice other Islamic countries often allow–to teach anatomy. In January 2002, New York Times reporter Norimitsu Onishi interviewed a student at Kandahar Medical College who had made the anguishing decision to dig up the bones of his beloved grandmother and share them with his classmates. Another student unearthed the remains of his former neighbor. “Yes, he was a good man,” the student told Onishi. “Naturally I felt bad about taking his skeleton…. I thought that if twenty people could benefit from it, it would be good.”

This sort of reasoned, pained sensitivity was rare in the heyday of British anatomy schools. The far more common tactic was to sneak into a graveyard and dig up someone else’s relative to study. The act became known as body snatching. It was a new crime, distinct from grave‑robbing, which involved the pilfering of jewels and heirlooms buried in tombs and crypts of the well‑to‑do. Being caught in possession of a corpse’s cufflinks was a crime, but being caught with the corpse itself carried no penalty. Before anatomy schools caught on, there were no laws on the books regarding the misappropriation of freshly dead humans.

And why would there be? Up until that point, there had been little reason, short of necrophilia,[4]to undertake such a thing.

Some anatomy instructors mined the timeless affinity of university students for late‑night pranks by encouraging their enrollees to raid graveyards and provide bodies for the class. At certain Scottish schools, in the 1700s, the arrangement was more formal: Tuition, writes Ruth Richardson, could be paid in corpses rather than cash.

Other instructors took the dismal deed upon themselves. These were not low‑life quacks. They were respectable members of their profession.

Colonial physician Thomas Sewell, who went on to become the personal physician to three U.S. presidents and to found what is now George Washington University Medical School, was convicted in 1818 of digging up the corpse of a young Ipswich, Massachusetts, woman for the purposes of dissection.

And then there were the anatomists who paid someone else to go digging. By 1828, the demands of London’s anatomy schools were such that ten full‑time body snatchers and two hundred or so part‑timers were kept busy throughout the dissecting “season.” (Anatomy courses were held only between October and May, to avoid the stench and swiftness of summertime decomposition.) According to a House of Commons testimony from that year, one gang of six or seven resurrectionists, as they were often called, dug up 312 bodies. The pay worked out to about $1,000 a year–some five to ten times the earnings of the average unskilled laborer–with summers off.

The job was immoral, and ugly to be sure, but probably less unpleasant than it sounds. The anatomists wanted freshly dead bodies, so the smell wasn’t really a problem. A body snatcher didn’t have to dig up the entire grave, but rather just the top end of it. A crowbar would then be slipped under the coffin lid and wrenched upward, snapping off the top foot or so. The corpse was fished out with a rope around the neck or under the arms, and the dirt, which had been piled on a tarp, would be slid back in.

The whole affair took less than an hour.

Many of the resurrectionists had held posts as gravediggers or assistants in anatomy labs, where they’d come into contact with the gangs and their doings. Drawn to the promise of higher pay and less confining hours, they abandoned legitimate posts to take up the shovel and sack. A few diary entries–transcribed from the anonymously written Diary of a Resurrectionist –yield some insight into the sort of people we’re talking about here:

Tuesday 3rd (November 1811). Went to look out and brought the Shovils from Bartholow,… Butler and me came home intoxsicated.

Tuesday 10th. Intoxsicated all day: at night went out & got 5 Bunhill Row. Jack all most buried.

Friday 27th…. Went to Harps, got 1 large and took it to Jack’s house, Jack, Bill, and Tom not with us, Geting drunk.

It is tempting to believe that the author’s impersonal references to the corpses belie some sense of discomfort with his activities. He does not dwell upon their looks or muse about their sorry fate. He cannot bring himself to refer to the dead as anything other than a size or a gender.

Only occasionally do the bodies merit a noun. (Most often “thing,” as in “Thing bad,” meaning “body decomposed.”) But more likely it was simply the man’s disinclination to sit down and write that accounts for the shorthand. Later entries show he couldn’t even be bothered so spell out “canines,” which appears as “Cns.” (When a “thing bad,” the “Cns” and other teeth were pulled and sold to dentists, for making dentures,[5]so as to keep the undertaking from being a complete loss.)

Body snatchers were common thugs; their motive, simple greed. But what of the anatomists? Who were these upstanding members of society who could commission the theft and semi‑public mutilation of someone’s dead grandmother? The best‑known of the London surgeon‑anatomists was Sir Astley Cooper. In public, Cooper denounced the resurrectionists, yet he not only sought out and retained their services, but encouraged those in his employ to take up the job. Thing bad.

Cooper was an outspoken defender of human dissection. “He must mangle the living if he has not operated on the dead” was his famous line. While his point is well taken and the medical schools’ plight was a difficult one, a little conscience would have served. Cooper was the type of man who not only evinced no compunction about cutting up strangers’ family members but happily sliced into his own former patients. He kept in touch with the family doctors of those he had operated on and, upon hearing of their passing, commissioned his resurrectionists to unearth them so that he might have a look at how his handiwork had held up. He paid for the retrieval of bodies of colleagues’ patients known to have interesting ailments or anatomical peculiarities. He was a man in whom a healthy passion for biology seemed to have metastasized into a sort of macabre eccentricity. In Things for the Surgeon , an account of body snatching by Hubert Cole, Sir Astley is said to have painted the names of colleagues onto pieces of bone and forced lab dogs to swallow them, so that when the bone was extracted during the dog’s dissection, the colleague’s name would appear in intaglio, the bone around the letters having been eaten away by the dog’s gastric acids. The items were handed out as humorous gifts. Cole doesn’t mention the colleagues’ reactions to the one‑of‑a‑kind name‑plates, but I would hazard a guess that the men made an effort to enjoy the joke and displayed the items prominently, at least when Sir Astley came calling. For Sir Astley wasn’t the sort of fellow whose ill will you wanted to take with you to your grave. As Sir Astley himself put it, “I can get anyone.”

Like the resurrectionists, the anatomists were men who had clearly been successful in objectifying, in their own minds at least, the dead human body. Not only did they view dissection and the study of anatomy as justification for unapproved disinterment, they saw no reason to treat the unearthed dead as entities worthy of respect. It didn’t bother them that the corpses would arrive at their doors, to quote Ruth Richardson, “compressed into boxes, packed in sawdust,… trussed up in sacks, roped up like hams…” So similar in their treatment were the dead to ordinary items of commerce that every now and then boxes would be mixed up in transit. James Moores Ball, author of The Sack‑’Em‑Up Men , tells the tale of the flummoxed anatomist who opened a crate delivered to his lab expecting a cadaver but found instead “a very fine ham, a large cheese, a basket of eggs, and a huge ball of yarn.” One can only imagine the surprise and very special disappointment of the party expecting very fine ham, cheese, eggs, or a huge ball of yarn, who found instead a well‑packed but quite dead Englishman.

It wasn’t so much the actual dissecting that smacked of disrespect. It was the whole street‑theater‑cum‑abattoir air of the proceedings. Engravings by Thomas Rowlandson and William Hogarth of eighteenth‑ and early‑nineteenth‑century dissecting rooms show cadavers’ intestines hanging like parade streamers off the sides of tables, skulls bobbing in boiling pots, organs strewn on the floor being eaten by dogs. In the background, crowds of men gawk and leer. While the artists were clearly editorializing upon the practice of dissection, written sources suggest the artworks were not far removed from the truth. Here is the composer Hector Berlioz, in an 1822 entry in his Memoirs , shedding considerable light on his decision to pursue music rather than medicine:

Robert… took me for the first time to the dissecting room. …At the sight of that terrible charnel‑house–fragments of limbs, the grinning heads and gaping skulls, the bloody quagmire underfoot and the atrocious smell it gave off, the swarms of sparrows wrangling over scraps of lung, the rats in their corner gnawing the bleeding vertebrae–such a feeling of revulsion possessed me that I leapt through the window of the dissecting room and fled for home as though Death and all his hideous train were at my heels.

And I would wager a fine ham and a huge ball of yarn that no anatomist of that era ever held a memorial service for the leftover pieces. Cadaver remainders were buried not out of respect but for lack of other options.

The burials were hastily done, always at night and usually out behind the building.

To avoid the problematic odors that tend to accompany a shallow burial, anatomists came up with some creative solutions to the flesh disposal problem. A persistent rumor had them in cahoots with the keepers of London’s wild animal menageries. Others were said to keep vultures on hand for the task, though if Berlioz is to be believed, the sparrows of the day were well up to the task. Richardson came across a reference to anatomists cooking down human bones and fat into “a substance like Spermaceti,” which they used to make candles and soap. Whether these were used in the anatomists’ homes or given away as gifts was not noted, but between these and the gastric‑juice‑etched nameplates, it’s safe to say you really didn’t want your name on an anatomist’s Christmas gift list.

And so it went. For nearly a century, the shortage of legally dissectable bodies pitted the anatomist against the private citizen. By and large, it was the poor who had most to lose. For over time, entrepreneurs came up with an arsenal of antiresurrectionist products and services, affordable only by the upper class. Iron cages called mortsafes could be set in concrete above the grave or underground, around the coffin. Churches in Scotland built graveyard “dead houses,” locked buildings where a body could be left to decompose until its structures and organs had disintegrated to the point where they were of no use to anatomists. You could buy patented spring‑closure coffins, coffins outfitted with cast‑iron corpse straps, double and even triple coffins. Appropriately, the anatomists were among the undertakers’ best customers. Richardson relates that Sir Astley Cooper not only went for the triple coffin option but had the whole absurd Chinese‑box affair housed in a hulking stone sarcophagus.

It was an Edinburgh anatomist named Robert Knox who instigated anatomy’s fatal PR blunder: the implicit sanctioning of murder for medicine. In 1828, one of Knox’s assistants answered the door to find a pair of strangers in the courtyard with a cadaver at their feet. This was business as usual for anatomists of the day, and so Knox invited the men in. Perhaps he made them a cup of tea, who knows. Knox was, like Astley, a man of high social bearing. Although the men, William Burke and William Hare, were strangers, he cheerfully bought the body and accepted their story that the cadaver’s relatives had made the body available for sale–though this was, given the public’s abhorrence of dissection, an unlikely scenario.

The body, it turns out, had been a lodger at a boardinghouse run by Hare and his wife, in an Edinburgh slum called Tanner’s Close. The man died in one of Hare’s beds, and, being dead, was unable to come up with the money he owed for the nights he’d stayed. Hare wasn’t one to forgive a debt, so he came up with what he thought to be a fair solution: He and Burke would haul the body to one of those anatomists they’d heard about over at Surgeons’ Square. There they would sell it, kindly giving the lodger the opportunity, in death, to pay off what he’d neglected to in life.

When Burke and Hare found out how much money could be made selling corpses, they set about creating some of their own. Several weeks later, a down‑and‑out alcoholic took ill with fever while staying at Hare’s flophouse. Figuring the man to be well on his way to cadaverdom anyway, the men decided to speed things along. Hare pressed a pillow to the man’s face while Burke laid his considerable body weight on top of him. Knox asked no questions and encouraged the men to come back soon. And they did, some fifteen times. The pair were either too ignorant to realize that the same money could be made digging up graves of the already dead or too lazy to undertake it.

A series of modern‑day Burke‑and‑Hare‑type killings took place barely ten years ago, in Barranquilla, Colombia. The case centered on a garbage scavenger named Oscar Rafael Hernandez, who in March 1992 survived an attempt to murder him and sell his corpse to the local medical school as an anatomy lab specimen.[6]Like most of Colombia, Barranquilla lacked an organized recycling program, and hundreds of the city’s destitute forge a living picking through garbage dumps for recyclables to sell. So scorned are these people that they–along with other social outcasts such as prostitutes and street urchins–are referred to as “disposables” and have often been murdered by right‑wing “social cleansing” squads. As the story goes, guards from Universidad Libre had asked Hernandez if he wanted to come to the campus to collect some garbage, and then bludgeoned him over the head when he arrived. A Los Angeles Times account of the case has Hernandez awakening in a vat of formaldehyde alongside thirty corpses, a colorful if questionable detail omitted from other descriptions of the case. Either way, Hernandez came to and escaped to tell his tale.

Activist Juan Pablo Ordoñez investigated the case and claims that Hernandez was one of at least fourteen Barranquilla indigents murdered for medicine–even though an organized willed body program existed.

According to Ordoñez’s report, the national police had been unloading bodies gleaned from their own, in‑house “social cleansing” activities and collecting $150 per corpse from the university coffers. The school’s security staff got wind of the setup and decided to get in on the action. At the time the investigation began, some fifty preserved bodies and body parts of questionable origin were found in the anatomy amphitheater. To date, no one from the university or the police has been arrested.

For his part, William Burke was eventually brought to justice. A crowd of more than 25,000 watched him hang. Hare was granted immunity, much to the disgust of the gallows crowd, who chanted “Burke Hare!”–meaning “Smother Hare,” “burke” having made its way into the popular vernacular as a synonym for “smother.” Hare probably did as much smothering as Burke, but “She’s been hared!” lacks the pleasing Machiavellian fricatives of “She’s been burked!” and the technicality is easily forgiven.

In a lovely sliver of poetic justice, Burke’s corpse was, in keeping with the law of the day, dissected. As the lecture had been about the human brain, it seems unlikely that the body cavity would have been opened and notably rearranged, but perhaps this was thrown in after the fact, as a crowd pleaser. The following day the lab was opened to the public, and some thirty thousand vindicated gawkers filed past. The post‑dissection cadaver was, by order of the judge, shipped to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh to have its bones made into a skeleton, which resides there to this day, along with one of several wallets made from Burke’s skin.[7]

Though Knox was never charged for his role in the murders, public sentiment held him accountable. The freshness of the bodies, the fact that one had its head and feet cut off and others had blood oozing from the nose or ears–all of this should have raised the bristly Knox eyebrows.

The anatomist clearly didn’t care. Knox further sullied his reputation by preserving one of Burke and Hare’s more comely corpses, the prostitute Mary Paterson, in a clear glass vat of alcohol in his lab.

When an inquiry by a lay committee into Knox’s role generated no formal action against the doctor, a mob gathered the following day with an effigy of Knox. (The thing must not have looked a great deal like the man, for they felt the need to label if. “Knox, the associate of the infamous Hare,” explained a large sign on its back.) The stuffed Knox was paraded through the streets to the house of the real Knox, where it was hung by its neck from a tree and then cut down and–fittingly–torn to pieces.

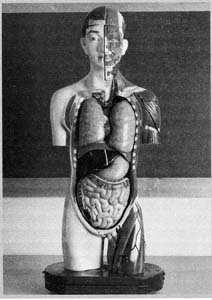

It was around this time that Parliament conceded that the anatomy problem had gotten a tad out of hand and convened a committee to brainstorm solutions. While the debate mainly focused on alternate sources of bodies–most notably, unclaimed corpses from hospitals, prisons, and workhouses– some physicians raised an interesting item of debate: Is human dissection really necessary? Can’t anatomy be learned from models, drawings, preserved prosections?

There have been times and places, in history, when the answer to the question “Is human dissection necessary?” was unequivocally yes. Here are some examples of what can happen when you try to figure out how a human body works without actually opening one up. In ancient China, Confucian doctrine considered dissection a defilement of the human body and forbade its practice. This posed a problem for the Father of Chinese Medicine, Huang Ti, who, around 2600 B.C., set out to write an authoritative medical and anatomical text (Nei Ch’ing , or Canon of Medicine) . As is evident from this passage–quoted in Early History of Human Anatomy –there are places where Huang is, through no fault of his own, rather clearly winging it:

The heart is a king, who rules over all organs of the body; the lungs are his executive, who carry out his orders; the liver is his commandant, who keeps up the discipline; the gall bladder, his attorney general… and the spleen, his steward who supervises the five tastes. There are three burning spaces–the thorax, the abdomen and the pelvis–which are together responsible for the sewage system of the body.

To Huang Ti’s credit, though, he managed, without ever disassembling a corpse, to figure out that “the blood of the body is under the control of the heart” and that “the blood current flows in a continuous circle and never stops.” In other words, the man figured out what William Harvey figured out, four thousand years before Harvey and without laying open any family members.

Imperial Rome gives us another nice example of what happens to medicine when the government frowns on human dissection. Galen, one of history’s most revered anatomists, whose texts went unchallenged for centuries, never once dissected a human cadaver. In his post as surgeon to the gladiators, he had a frequent, if piecemeal, window on the human interior in the form of gaping sword wounds and lion claw lacerations.

He also dissected a good sum of animals, preferably apes, which he believed to be anatomically identical to humans, especially, he maintained, if the ape had a round face. The great Renaissance anatomist Vesalius later pointed out that there are two hundred anatomical differences between apes and humans in skeletal structure alone. (Whatever Galen’s shortcomings as a comparative anatomist, the man is to be respected for his ingenuity, for procuring apes in ancient Rome can’t have been easy.) He got a lot right, it’s just that he also got a fair amount wrong. His drawings showed five‑lobed livers and hearts with three ventricles.

The ancient Greeks were similarly adrift when it came to human anatomy. Like Galen, Hippocrates never dissected a human cadaver–he called dissection “unpleasant if not cruel.” According to the book Early History of Human Anatomy , Hippocrates referred to tendons as “nerves” and believed the human brain to be a mucus‑secreting gland. Though I found this information surprising, this being the Father of Medicine we are talking about, I did not question it. You do not question an author who appears on the title page as “T.V.N. Persaud, M.D., Ph.D., D.Sc, F.R.C.Path. (Lond.), F.F.Path. (R.C.P.I.), F.A.C.O.G.” Who knows, perhaps history erred in bestowing upon Hippocrates the title Father of Medicine. Perhaps T.V.N. Persaud is the Father of Medicine.

It’s no coincidence that the man who contributed the most to the study of human anatomy, the Belgian Andreas Vesalius, was an avid proponent of do‑it‑yourself, get‑your‑fussy‑Renaissance‑shirt‑dirty anatomical dissection. Though human dissection was an accepted practice in the Renaissance‑era anatomy class, most professors shied away from personally undertaking it, preferring to deliver their lectures while seated in raised chairs a safe and tidy remove from the corpse and pointing out structures with a wooden stick while a hired hand did the slicing. Vesalius disapproved of this practice, and wasn’t shy about his feelings.

In C. D. O’Malley’s biography of the man, Vesalius likens the lecturers to “jackdaws aloft in their high chair, with egregious arrogance croaking things they have never investigated but merely committed to memory from the books of others. Thus everything is wrongly taught, …and days are wasted in ridiculous questions.”

Vesalius was a dissector such as history had never seen. This was a man who encouraged his students to “observe the tendons while dining on any animal.” While studying medicine in Belgium, he not only dissected the corpses of executed criminals but snatched them from the gibbet himself.

Vesalius produced a series of richly detailed anatomical plates and text called De Humani Corporis Fabrica , the most venerated anatomy book in history. The question then becomes, was it necessary, once the likes of Vesalius had pretty much figured out the basics, for every student of anatomy to get right in there and figure them out all over again? Why couldn’t models and preserved prosections be used to teach anatomy? Do gross anatomy labs reinvent the wheel? The questions were especially relevant in Knox’s day, given the way in which bodies were procured, but they are still relevant today.

I asked Hugh Patterson about this and learned that, in fact, whole‑cadaver dissection is being phased out at some medical schools. Indeed, the gross anatomy course I visited at UCSF was the last one in which students will dissect entire cadavers. Beginning the following semester, they would be studying pro‑sections–embalmed sections of the body cut and prepared so as to display key anatomical features and systems. Over at the University of Colorado, the Center for Human Simulation is leading the charge toward digital anatomy instruction. In 1993, they froze a cadaver and sanded off a millimeter cross section at a time, photographing each new view–1,871 in all–to create an on‑screen, maneuverable 3‑D rendition of the man and all his parts, a sort of flight simulator for students of anatomy and surgery.

The changes in the teaching of anatomy have nothing to do with cadaver shortages or public opinion about dissection; they have everything to do with time. Despite the immeasurable advances made in medicine over the past century, the material must be covered in the same number of years. Suffice it to say there’s a lot less time for dissection than there was in Astley Cooper’s day.

I asked the students in Patterson’s gross anatomy lab how they’d feel if they hadn’t had a chance to dissect a body. While some, said they would feel cheated–that the gross anatomy cadaver experience was a physician’s rite of passage–many expressed approval. “There were days,” said one, “when it all clicked and I gained a sort of understanding I could never have gotten from a book. But there were other days, a lot of days, when coming up here and spending two hours felt like a huge waste of time.”

But gross anatomy lab is not just about learning anatomy. It is about confronting death. Gross anatomy provides the medical student with what is very often his or her first exposure to a dead body; as such, it has long been considered a vital, necessary step in the doctor’s education. But what was learned, up until quite recently, was not respect and sensitivity, but the opposite. The traditional gross anatomy lab represented a sort of sink‑or‑swim mentality about dealing with death. To cope with what was being asked of them, medical students had to find ways to desensitize themselves. They quickly learned to objectify cadavers, to think of the dead as structures and tissues, and not a former human being. Humor–at the cadaver’s expense–was tolerated, condoned even. “There was a time not all that long ago,” says Art Dalley, director of the Medical Anatomy Program at Vanderbilt University, “when students were taught to be insensitive, as a coping mechanism.”

Modern educators feel there are better, more direct ways to address death than handing students a scalpel and assigning them a corpse. In Patterson’s anatomy class at UCSF, as in many others, some of the time saved by eliminating full‑body dissection will be devoted to a special unit on death and dying. If you’re going to bring in an outsider to teach students about death, a hospice patient or grief counselor surely has as much to offer as a dead man does.

If the trend continues, medicine may find itself with something unimaginable two centuries ago: a surplus of cadavers. It is remarkable how deeply and how quickly public opinion regarding dissection and body donation has come around. I asked Art Dalley what accounted for the change. He cited a combination of factors. The 1960s saw the first heart transplant and the passing of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, both of which raised awareness of the need for organs for transplantation and of body donation as an option. Around the same time, Dalley says, there was a notable increase in the cost of funerals. This was followed by the publication of The American Way of Death –Jessica Mitford’s biting exposé of the funeral industry– and a sudden upswing in the popularity of cremation. Willing one’s body to science began to be seen as another acceptable– and, in this case, altruistic–alternative to burial.

To those factors I would add the popularization of science. The gains in the average person’s understanding of biology have, I imagine, worked to dissolve the romance of death and burial–the lingering notion of the cadaver as some beatific being in an otherworldly realm of satin and chorale music, the well‑groomed almost‑human who simply likes to sleep a lot, underground, in his clothing. The people of the 1800s seemed to feel that burial culminated in a fate less ghastly than that of dissection.

But that, as we’ll see, is hardly the case.

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 2294;