LIFE AFTER DEATH

On Human Decay and What Can Be Done About It

Out behind the University of Tennessee Medical Center is a lovely, forested grove with squirrels leaping in the branches of hickory trees and birds calling and patches of green grass where people lie on their backs in the sun, or sometimes the shade, depending on where the researchers put them.

This pleasant Knoxville hillside is a field research facility, the only one in the world dedicated to the study of human decay. The people lying in the sun are dead. They are donated cadavers, helping, in their mute, fragrant way, to advance the science of criminal forensics. For the more you know about how dead bodies decay–the biological and chemical phases they go through, how long each phase lasts, how the environment affects these phases–the better equipped you are to figure out when any given body died: in other words, the day and even the approximate time of day it was murdered. The police are pretty good at pinpointing approximate time of death in recently dispatched bodies. The potassium level of the gel inside the eyes is helpful during the first twenty‑four hours, as is algor mortis –the cooling of a dead body; barring temperature extremes, corpses lose about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit per hour until they reach the temperature of the air around them. (Rigor mortis is more variable: It starts a few hours after death, usually in the head and neck, and continues, moving on down the body, finishing up and disappearing anywhere from ten to forty‑eight hours after death.)

If a body has been dead longer than three days, investigators turn to entomological clues (e.g., how old are these fly larvae?) and stages of decay for their answers. And decay is highly dependent on environmental and situational factors. What’s the weather been like? Was the body buried? In what? Seeking better understanding of the effects of these factors, the University of Tennessee (UT) Anthropological Research Facility, as it is blandly and vaguely called, has buried bodies in shallow graves, encased them in concrete, left them in car trunks and man‑made ponds, and wrapped them in plastic bags. Pretty much anything a killer might do to dispose of a dead body the researchers at UT have done also.

To understand how these variables affect the time line of decomposition, you must be intimately acquainted with your control scenario: basic, unadulterated human decay. That’s why I’m here. That’s what I want to know: When you let nature take its course, just exactly what course does it take?

My guide to the world of human disassembly is a patient, amiable man named Arpad Vass. Vass has studied the science of human decomposition for more than a decade. He is an adjunct research professor of forensic anthropology at UT and a senior staff scientist at the nearby Oak Ridge National Laboratory. One of Arpad’s projects at ORNL has been to develop a method of pinpointing time of death by analyzing tissue samples from the victim’s organs and measuring the amounts of dozens of different time‑dependent decay chemicals. This profile of decay chemicals is then matched against the typical profiles for that tissue for each passing postmortem hour. In test runs, Arpad’s method has determined the time of death to within plus or minus twelve hours.

The samples he used to establish the various chemical breakdown time lines came from bodies at the decay facility. Eighteen bodies, some seven hundred samples in all. It was an unspeakable task, particularly in the later stages of decomposition, and particularly for certain organs. “We’d have to roll the bodies over to get at the liver,” recalls Arpad. The brain he got to using a probe through the eye orbit. Interestingly, neither of these activities was responsible for Arpad’s closest brush with on‑the‑job regurgitation. “One day last summer,” he says weakly, “I inhaled a fly. I could feel it buzzing down my throat.”

I have asked Arpad what it’s like to do this sort of work. “What do you mean?” he asked me back. “You want a vivid description of what’s going through my brain as I’m cutting through a liver and all these larvae are spilling out all over me and juice pops out of the intestines?” I kind of did, but I kept quiet. He went on: “I don’t really focus on that. I try to focus on the value of the work. It takes the edge off the grotesqueness.”

As for the humanness of his specimens, that no longer disturbs him.

Though it once did. He used to lay the bodies on their stomachs so he didn’t have to see their faces.

This morning, Arpad and I are riding in the back of a van being driven by the lovable and agreeable Ron Walli, one of ORNL’s media relations guys. Ron pulls into a row of parking spaces at the far end of the UT Medical Center lot, labeled G section. On hot summer days, you can always find a parking space in G section, and not just because it’s a longer walk to the hospital. G section is bordered by a tall wooden fence topped with concertina wire, and on the other side of the fence are the bodies. Arpad steps down from the van. “Smell’s not that bad today,” he says. His “not that bad” has that hollow, over‑upbeat tone one hears when spouses back over flowerbeds or home hair coloring goes awry.

Ron, who began the trip in a chipper mood, happily pointing out landmarks and singing along with the radio, has the look of a condemned man. Arpad sticks his head in the window. “Are you coming in, Ron, or are you going to hide in the car again?” Ron steps out and glumly follows. Although this is his fourth time in, he says he’l never get used to it. It’s not the fact that they’re dead–Ron saw accident victims routinely in his former post as a newspaper reporter–it’s the sights and smells of decay. “The smell just stays with you,” he says. “Or that’s what you imagine. I must have washed my hands and face twenty times after I got back from my first time out here.”

Just inside the gate are two old‑fashioned metal mailboxes on posts, as though some of the residents had managed to convince the postal service that death, like rain or sleet or hail, should not stay the regular delivery of the U.S. Mail. Arpad opens one and pulls turquoise rubber surgical gloves from a box, two for him and two for me. He knows not to offer them to Ron.

“Let’s start over there.” Arpad is pointing to a large male figure about twenty feet distant. From this distance, he could be napping, though there is something in the lay of the arms and the stillness of him that suggests something more permanent. We walk toward the man. Ron stays near the gate, feigning interest in the construction details of a toolshed.

Like many big‑bellied people in Tennessee, the dead man is dressed for comfort. He wears gray sweatpants and a single‑pocket white T‑shirt.

Arpad explains that one of the graduate students is studying the effects of clothing on the decay process. Normally, they are naked.

The cadaver in the sweatpants is the newest arrival. He will be our poster man for the first stage of human decay, the “fresh” stage. (“Fresh,” as in fresh fish, not fresh air. As in recently dead but not necessarily something you want to put your nose right up to.) The hallmark of fresh‑stage decay is a process called autolysis, or self‑digestion. Human cells use enzymes to cleave molecules, breaking compounds down into things they can use.

While a person is alive, the cells keep these enzymes in check, preventing them from breaking down the cells’ own walls. After death, the enzymes operate unchecked and begin eating through the cell structure, allowing the liquid inside to leak out.

“See the skin on his fingertips there?” says Arpad. Two of the dead man’s fingers are sheathed with what look like rubber fingertips of the sort worn by accountants and clerks. “The liquid from the cells gets between the layers of skin and loosens them. As that progresses, you see skin sloughage.” Mortuary types have a different name for this. They call it “skin slip.” Sometimes the skin of the entire hand will come off. Mortuary types don’t have a name for this, but forensics types do. It’s called “gloving.”

“As the process progresses, you see giant sheets of skin peeling off the body,” says Arpad. He pulls up the hem of the man’s shirt to see if, indeed, giant sheets are peeling. They are not, and that’s okay.

Something else is going on. Squirming grains of rice are crowded into the man’s belly button. It’s a rice grain mosh pit. But rice grains do not move.

These cannot be grains of rice. They are not. They are young flies.

Entomologists have a name for young flies, but it is an ugly name, an insult. Let’s not use the word “maggot.” Let’s use a pretty word. Let’s use “hacienda.”

Arpad explains that the flies lay their eggs on the body’s points of entry: the eyes, the mouth, open wounds, genitalia. Unlike older, larger haciendas, the little ones can’t eat through skin. I make the mistake of asking Arpad what the little haciendas are after.

Arpad walks around to the corpse’s left foot. It is bluish and the skin is transparent. “See the [haciendas] under the skin? They’re eating the subcutaneous fat. They love fat.” I see them. They are spaced out, moving slowly. It’s kind of beautiful, this man’s skin with these tiny white slivers embedded just beneath its surface. It looks like expensive Japanese rice paper. You tell yourself these things.

Let us return to the decay scenario. The liquid that is leaking from the enzyme‑ravaged cells is now making its way through the body. Soon enough it makes contact with the body’s bacteria colonies: the ground troops of putrefaction. These bacteria were there in the living body as well, in the intestinal tract, in the lungs, on the skin–the places that came in contact with the outside world. Life is looking rosy for our one‑celled friends. They’ve already been enjoying the benefits of a decommissioned human immune system, and now, suddenly, they’re awash with this edible goo, issuing from the ruptured cells of the intestine lining. It’s raining food. As will happen in times of plenty, the population swells.

Some of the bacteria migrate to the far frontiers of the body, traveling by sea, afloat in the same liquid that keeps them nourished. Soon bacteria are everywhere. The scene is set for stage two: bloat.

The life of a bacterium is built around food. Bacteria don’t have mouths or fingers or Wolf Ranges, but they eat. They digest. They excrete. Like us, they break their food down into its more elemental components. The enzymes in our stomachs break meat down into proteins. The bacteria in our gut break those proteins down into amino acids; they take up where we leave off. When we die, they stop feeding on what we’ve eaten and begin feeding on us. And, just as they do when we’re alive, they produce gas in the process. Intestinal gas is a waste product of bacteria metabolism.

The difference is that when we’re alive, we expel that gas. The dead, lacking workable stomach muscles and sphincters and bedmates to annoy, do not. Cannot. So the gas builds up and the belly bloats. I ask Arpad why the gas wouldn’t just get forced out eventually. He explains that the small intestine has pretty much collapsed and sealed itself off. Or that there might be “something” blocking its egress. Though he allows, with some prodding, that a little bad air often does, in fact, slip out, and so, as a matter of record, it can be said that dead people fart. It needn’t be, but it can.

Arpad motions me to follow him up the path. He knows where a good example of the bloat stage can be found.

Ron is still down by the shed, effecting some sort of gratuitous lawn mower maintenance, determined to avoid the sights and smells beyond the gate. I call for him to join me. I feel the need for company, someone else who doesn’t see this sort of thing every day. Ron follows, looking at his sneakers. We pass a skeleton six feet seven inches tall and dressed in a red Harvard sweatshirt and sweatpants. Ron’s eyes stay on his shoes. We pass a woman whose sizable breasts have decomposed, leaving only the skins, like flattened bota bags upon her chest. Ron’s eyes stay on his shoes.

Bloat is most noticeable in the abdomen, Arpad is saying, where the largest numbers of bacteria are, but it happens in other bacterial hot spots, most notably the mouth and genitalia. “In the male, the penis and especially the testicles can become very large.”

“Like how large?” (Forgive me.)

“I don’t know. Large.”

“Softball large? Watermelon large?”

“Okay, softball.” Arpad Vass is a man with infinite reserves of patience, but we are scraping the bottom of the tank.

Arpad continues. Bacteria‑generated gas bloats the lips and the tongue, the latter often to the point of making it protrude from the mouth: In real life as it is in cartoons. The eyes do not bloat because the liquid long ago leached out. They are gone. Xs. In real life as it is in cartoons.

Arpad stops and looks down. “That’s bloat.” Before us is a man with a torso greatly distended. It is of a circumference I more readily associate with livestock. As for the groin, it is difficult to tell what’s going on; insects cover the area, like something he is wearing. The face is similarly obscured. The larvae are two weeks older than their peers down the hill and much larger. Where before they had been grains of rice, here they are cooked rice. They live like rice, too, pressed together: a moist, solid entity.

If you lower your head to within a foot or two of an infested corpse (and this I truly don’t recommend), you can hear them feeding. Arpad pinpoints the sound: “Rice Krispies.” Ron frowns. Ron used to like Rice Krispies.

Bloat continues until something gives way. Usually it is the intestines.

Every now and then it is the torso itself. Arpad has never seen it, but he has heard it, twice. “A rending, ripping noise” is how he describes it.

Bloat is typically short‑lived, perhaps a week and it’s over. The final stage, putrefaction and decay, lasts longest.

Putrefaction refers to the breaking down and gradual liquefaction of tissue by bacteria. It is going on during the bloat phase–for the gas that bloats a body is being created by the breakdown of tissue–but its effects are not yet obvious.

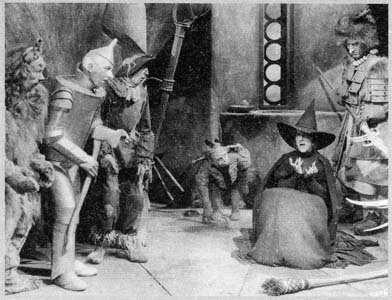

Arpad continues up the wooded slope. “This woman over here is farther along,” he says. That’s a nice way to say it. Dead people, unembalmed ones anyway, basically dissolve; they collapse and sink in upon themselves and eventually seep out onto the ground. Do you recall the Margaret Hamilton death scene in The Wizard of Oz ? (“I’m melting!”) Putrefaction is more or less a slowed‑down version of this. The woman lies in a mud of her own making. Her torso appears sunken, its organs gone–leached out onto the ground around her.

The digestive organs and the lungs disintegrate first, for they are home to the greatest numbers of bacteria; the larger your work crew, the faster the building comes down. The brain is another early‑departure organ.

“Because all the bacteria in the mouth chew through the palate,” explains Arpad. And because brains are soft and easy to eat. “The brain liquefies very quickly. It just pours out the ears and bubbles out the mouth.”

Up until about three weeks, Arpad says, remnants of organs can still be identified. “After that, it becomes like a soup in there.” Because he knew I was going to ask, Arpad adds, “Chicken soup. It’s yellow.”

Ron turns on his heels. “Great.” We ruined Rice Krispies for Ron, and now we have ruined chicken soup.

Muscles are eaten not only by bacteria, but by carnivorous beetles. I wasn’t aware that meat‑eating beetles existed, but there you go.

Sometimes the skin gets eaten, sometimes not. Sometimes, depending on the weather, it dries out and mummifies, whereupon it is too tough for just about anyone’s taste. On our way out, Arpad shows us a skeleton with mummified skin, lying facedown. The skin has remained on the legs as far as the tops of the ankles. The torso, likewise, is covered, about up to the shoulder blades. The edge of the skin is curved, giving the appearance of a scooped neckline, as on a dancer’s leotard. Though naked, he seems dressed. The outfit is not as colorful or, perhaps, warm as a Harvard sweatsuit, but more fitting for the venue.

We stand for a minute, looking at the man.

There is a passage in the Buddhist Sutra on Mindfulness called the Nine Cemetery Contemplations. Apprentice monks are instructed to meditate on a series of decomposing bodies in the charnel ground, starting with a body “swollen and blue and festering,” progressing to one “being eaten by…different kinds of worms,” and moving on to a skeleton, “without flesh and blood, held together by the tendons.” The monks were told to keep meditating until they were calm and a smile appeared on their faces. I describe this to Arpad and Ron, explaining that the idea is to come to peace with the transient nature of our bodily existence, to overcome the revulsion and fear. Or something.

We all stare at the man. Arpad swats at flies.

“So,” says Ron. “Lunch?”

Outside the gate, we spend a long time scraping the bottoms of our boots on a curb. You don’t have to step on a body to carry the smells of death with you on your shoes. For reasons we have just seen, the soil around a corpse is sodden with the liquids of human decay. By analyzing the chemicals in this soil, people like Arpad can tell if a body has been moved from where it decayed. If the unique volatile fatty acids and compounds of human decay aren’t there, the body didn’t decompose there.

One of Arpad’s graduate students, Jennifer Love, has been working on an aroma scan technology for estimating time of death. Based on a technology used in the food and wine industries, the device, now being funded by the FBI, would be a sort of hand‑held electronic nose that could be waved over a body and used to identify the unique odor signature that a corpse puts off at different stages of decay.

I tell them that the Ford Motor Company developed an electronic nose programmed to identify acceptable “new car smell.” Car buyers expect their purchases to smell a certain way: leathery and new, but with no vinyl off‑gassy smells. The nose makes sure the cars comply. Arpad observes that the new‑car‑smell electronic nose probably uses a technology similar to what the electronic nose for cadavers would use.

“Just don’t get ’em confused,” deadpans Ron. He is imagining a young couple, back from a test drive, the woman turning to her husband and saying: “You know, that car smelled like a dead person.”

It is difficult to put words to the smell of decomposing human. It is dense and cloying, sweet but not flower‑sweet. Halfway between rotting fruit and rotting meat. On my walk home each afternoon, I pass a fetid little produce store that gets the mix almost right, so much so that I find myself peering behind the papaya bins for an arm or a glimpse of naked feet.

Barring a visit to my neighborhood, I would direct the curious to a chemical supply company, from which one can order synthetic versions of many of these volatiles. Arpad’s lab has rows of labeled glass vials: Skatole, Indole, Putrescine, Cadaverine. The moment wherein I uncorked the putrescine in his office may well be the moment he began looking forward to my departure. Even if you’ve never been around a decaying body, you’ve smelled putrescine. Decaying fish throws off putrescine, a fact I learned from a gripping Journal of Food Science article entitled “Post‑Mortem Changes in Black Skipjack Muscle During Storage in Ice.” This fits in with something Arpad told me. He said he knew a company that manufactured a putrescine detector, which doctors could use in place of swabs and cultures to diagnose vaginitis or, I suppose, a job at the skipjack cannery.

The market for synthetic putrescine and cadaverine is small, but devoted.

The handlers of “human remains dogs” use these compounds for training.[8]Human remains dogs are distinct from the dogs that search for escaped felons and the dogs that search for whole cadavers. They are trained to alert their owners when they detect the specific scents of decomposed human tissue. They can pinpoint the location of a corpse at the bottom of a lake by sniffing the water’s surface for the gases and fats that float up from the rotting remains. They can detect the lingering scent molecules of a decomposing body up to fourteen months after the killer lugged it away.

I had trouble believing this when I heard it. I no longer have trouble. The soles of my boots, despite washing and soaking in Clorox, would smell of corpse for months after my visit.

Ron drives us and our little cloud of stink to a riverside restaurant for lunch. The hostess is young and pink and clean‑looking. Her plump forearms and tight‑fitting skin are miracles. I imagine her smelling of talcum powder and shampoo, the light, happy smells of the living. We stand apart from the hostess and the other customers, as though we were traveling with an ill‑tempered, unpredictable dog. Arpad signals to the hostess that we are three. Four, if you count The Smell.

“Would you like to sit indoors…?”

Arpad cuts her off. “Outdoors. And away from people.”

That is the story of human decay. I would wager that if the good people of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had known what happens to dead bodies in the sort of detail that you and I now know, dissection might not have seemed so uniquely horrific. Once you’ve seen bodies dissected, and once you’ve seen them decomposing, the former doesn’t seem so dreadful. Yes, the people of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were buried, but that only served to draw out the process. Even in a coffin six feet deep, the body eventually decomposes. Not all the bacteria living in a human body require oxygen; there are plenty of anaerobic bacteria up to the task.

Nowadays, of course, we have embalming. Does this mean we are spared the unsavory fate of gradual liquefaction? Has modern mortuary science created an eternity free from unpleasant mess and stains? Can the dead be aesthetically pleasing? Let’s go see!

An eye cap is a simple ten‑cent piece of plastic. It is slightly larger than a contact lens, less flexible, and considerably less comfortable. The plastic is repeatedly lanced through, so that small, sharp spurs stick up from its surface. The spurs work on the same principle as those steel spikes that threaten Severe Tire Damage on behalf of rental car companies: The eyelid will come down over an eye cap, but, once closed, will not easily open back up. Eye caps were invented by a mortician to help dead people keep their eyes shut.

There have been times this morning when I wished that someone had outfitted me with a pair of eye caps. I’ve been standing around, eyelids up, in the basement embalming room of the San Francisco College of Mortuary Science.

Upstairs is a working mortuary, and above it are the classrooms and offices of the college, one of the nation’s oldest and best‑respected.[9]In exchange for a price break in the cost of embalming and other mortuary services, customers agree to let students practice on their loved ones. Like getting a $5 haircut at the Vidal Sassoon Academy, sort of, sort of not.

I had called the college to get answers about embalming: How long does it preserve corpses, and in what form? Is it possible to never decompose?

How does it work? They agreed to answer my questions, and then they asked me one. Did I want to come down and see how it’s done? I did, sort of, sort of not.

Presiding at the embalming table today are final‑semester students Theo Martinez and Nicole D’Ambrogio. Theo, a dark‑haired man of thirty‑nine with a long, distinguished face and narrow build, turned to mortuary science after a string of jobs in credit unions and travel agencies. He says he liked the fact that mortuary jobs often include housing. (Before cell phones and pagers, most funeral homes were built with apartments, so that someone was always there should a call come in at night.) For the beautiful and glossy‑haired Nicole, episodes of Quincy sparked an interest in the career, which is a little puzzling, because Quincy, if I recall, was a pathologist. (No matter what they say, the answer never quite satisfies.) The pair are garbed in plastic and latex, as am I and anyone else who plans to enter the “splash area.” They are working with blood; the garments are a precaution against it and all it may bring on: HIV, hepatitis, stains on your shirt.

The object of their attentions at the moment is a seventy‑five‑year‑old man, or a three‑week‑old cadaver, however you prefer to think of it. The man had donated his body to science, but, owing to its having been autopsied, science politely declined. An anatomy lab is as choosy as a pedigreed woman seeking love: You can’t be too fat or too tall or have any communicable diseases. Following a three‑week sojourn in a university refrigerator, the cadaver wound up here. I have agreed to disguise any identifying features, though I suspect that the dehydrating air of refrigeration has gotten a jump on the task. He looks gaunt and desiccated. Something of the old parsnip about him.

Before the embalming begins, the exterior of the corpse is cleaned and groomed, as it would be were this man to be displayed in an open casket or presented to the family for a private viewing. (In reality, when the students are through, no one but the cremation furnace attendant will see him.) Nicole swabs the mouth and eyes with disinfectant, then rinses both with a jet of water. Though I know the man to be dead, I expect to see him flinch when the cotton swab hits his eye, to cough and sputter when the water hits the back of his throat. His stillness, his deadness, is surreal.

The students move purposefully. Nicole is looking in the man’s mouth.

Her hand rests sweetly on his chest. Concerned, she calls Theo over to look. They talk quietly and then he turns to me. “There’s material sitting in the mouth,” he says.

I nod, picturing corduroy, swatches of gingham. “Material?”

“Purge,” offers Nicole. It’s not helping.

Hugh “Mack” McMonigle, an instructor at the college, who is supervising this morning’s session, steps up beside me. “What happened is that whatever was in the stomach found its way into the mouth.” Gases created by bacterial decay build up and put pressure on the stomach, squeezing its contents back up the esophagus and into the mouth. The situation appears not to bother Theo and Nicole, though purge is a relatively infrequent visitor to the embalming room.

Theo explains that he is going to use an aspirator. As if to distract me from what I am seeing, he keeps up a friendly patter. “The Spanish for ‘vacuum’ is aspiradora .”

Before switching on the aspirator, Theo takes a cloth to the man’s chin and wipes away a substance that looks but surely doesn’t taste like chocolate syrup. I ask him how he copes with the unpleasantnesses of dealing with dead strangers’ bodies and secretions. Like Arpad Vass, he says that he tries to focus on the positives. “If there are parasites or the person has dirty teeth or they didn’t wipe their nose before they died, you’re improving the situation, making them more presentable.”

Theo is single. I ask him whether studying to be a mortician has been having a deleterious effect on his love life. He straightens up and looks at me. “I’m short, I’m thin, I’m not rich. I would say my career choice is in fourth place in limiting my effectiveness as a single adult.” (It’s possible that it helped. Within a year, he would be married.)

Next Theo coats the face with what I assume to be some sort of disinfecting lotion, which looks a lot like shaving cream. The reason that it looks a lot like shaving cream, it turns out, is that it is. Theo slides a new blade into a razor. “When you shave a decedent, it’s really different.”

“I bet.”

“The skin isn’t able to heal, so you have to be really careful about nicks.

One shave per razor, and then you throw it away.” I wonder whether the man, in his dying days, ever stood before a mirror, razor in hand, wondering if it might be his last shave, unaware of the actual last shave that fate had arranged for him.

“Now we’re going to set the features,” says Theo. He lifts one of the man’s eyelids and packs tufts of cotton underneath to fill out the lid the way the man’s eyeballs once did. Oddly, the culture I associate most closely with cotton, the Egyptians, did not use their famous Egyptian cotton for plumping out withered eyes. The ancient Egyptians put pearl onions in there. Onions . Speaking for myself, if I had to have a small round martini garnish inserted under my eyelids, I would go with olives.

On top of the cotton go a pair of eye caps. “People would find it disturbing to find the eyes open,” explains Theo, and then he slides down the lids. In the corner of my viewing screen, my brain displays a special pull‑out graphic, an animated close‑up of the little spurs in action. Madre de dio! Aspiradora! Come the day, you won’t be seeing me in an open casket.

As a feature of the common man’s funeral, the open casket is a relatively recent development: around 150 years. According to Mack, it serves several purposes, aside from providing what undertakers call “the memory picture.” It reassures the family that, one, their loved one is unequivocally dead and not about to be buried alive, and, two, that the body in the casket is indeed their loved one, and not the stiff from the container beside his. I read in The Principles and Practice of Embalming that it came into vogue as a way for embalmers to show off their skills. Mack disagrees, noting that long before embalming became commonplace, corpses on ice inside their caskets were displayed at funerals. (I am inclined to believe Mack, this being a book that includes the passage “Many of the body tissues also possess some measure of immortality if they can be kept under proper conditions…. Theoretically, it is possible in this way to grow a chicken heart to the size of the world.”)

“Did you already go in the nose?” Nicole is holding aloft tiny chrome scissors. Theo says no. She goes in, first to trim the hair, then with the disinfectant. “It gives the decedent some dignity,” she says, plunging wadded cotton into and out of his left nostril.

I like the term “decedent.” It’s as though the man weren’t dead, but merely involved in some sort of protracted legal dispute. For evident reasons, mortuary science is awash with euphemisms. “Don’t say stiff, corpse, cadaver,” scolds The Principles and Practice of Embalming . “Say decedent, remains or Mr. Blank. Don’t say ‘keep.’ Say ‘maintain preservation.’ … “Wrinkles are ‘acquired facial markings.’ Decomposed brain that filters down through a damaged skull and bubbles out the nose is ‘frothy purge.’”

The last feature to be posed is the mouth, which will hang open if not held shut. Theo is narrating for Nicole, who is using a curved needle and heavy‑duty string to suture the jaws together. “The goal is to reenter through the same hole and come in behind the teeth,” says Theo. “Now she’s coming out one of the nostrils, across the septum, and then she’s going to reenter the mouth. There are a variety of ways of closing the mouth,” he adds, and then he begins talking about something called a needle injector. I pose my own mouth to resemble the mouth of someone who is quietly horrified, and this works quite well to close Theo’s mouth.

The suturing proceeds in silence.

Theo and Nicole step back and regard their work. Mack nods. Mr. Blank is ready for embalming.

Modern embalming makes use of the circulatory system to deliver a liquid preservative to the body’s cells to halt autolysis and put decay on hold. Just as blood in the vessels and capillaries once delivered oxygen and nutrients to the cells, now those same vessels, emptied of blood, are delivering embalming fluid. The first people known to attempt arterial embalming[10]were a trio of Dutch biologists and anatomists named Swammerdam, Ruysch, and Blanchard, who lived in the late 1600s. The early anatomists were dealing with a chronic shortage of bodies for dissection, and consequently were motivated to come up with ways to preserve the ones they managed to obtain. Blanchard’s textbook was the first to cover arterial embalming. He describes opening up an artery, flushing the blood out with water, and pumping in alcohol. I’ve been to frat parties like that.

Arterial embalming didn’t begin to catch on in earnest until the American Civil War. Up until this point, dead U.S. soldiers were buried more or less where they fell. Their families had to send a written request for disinterment and ship a coffin capable of being hermetically sealed to the nearest quartermaster office, whereupon the quartermaster officer would assign a team of men to dig up the remains and deliver them to the family. Often the coffins that the families sent were not hermetically sealed–who knew what “hermetically” meant? Who knows now?–and they soon began to stink and leak. At the urgent pleadings of the beleaguered delivery brigades, the army set about embalming its dead, some 35,000 in all.

One fine day in 1861, a twenty‑four‑year‑old colonel named Elmer Ellsworth was shot and killed as he seized a Confederate flag from atop a hotel, his rank and courage a testimony to the motivating powers of a humiliating first name. The colonel was given a hero’s send‑off and a first‑class embalming at the hands of one Thomas Holmes, the Father of Embalming.[11]The public filed past Elmer in his casket, looking every bit the soldier and nothing at all the decomposing body. Embalming received another boost four years later, when Abe Lincoln’s embalmed body traveled from Washington to his hometown in Illinois. The train ride amounted to a promotional tour for funerary embalming, for wherever the train stopped, people came to view him, and more than a few must have noted that he looked a whole lot better in his casket than Grandmama had looked in hers. Word spread and the practice grew, like a chicken heart, and soon the whole nation was sending their decedents in to be posed and preserved.

After the war, Holmes set up a business selling his patented embalming fluid, Innominata, to embalmers, but otherwise began to distance himself from the mortuary trade. He opened a drugstore, manufactured root beer, and invested in a health spa, and between the three of them managed to squander his considerable savings. He never married and fathered no children (other than Embalming), but it wouldn’t be accurate to say he lived alone. According to Christine Quigley, author of The Corpse: A History , he shared his Brooklyn house with samples of his war‑era handiwork: Embalmed bodies were stored in the closets, and heads sat on tables in the living room. Not all that surprisingly, Holmes began to go insane, spending his final years in and out of institutions. At seventy, he was placing ads in mortuary trade journals for a rubber‑coated canvas body removal bag that could, he suggested, double as a sleeping bag . Shortly before he died, Holmes is said to have requested that he not be embalmed, though whether this was a function of sanity or insanity was never made clear.

Theo is feeling around on Mr. Blank’s neck. “We’re in search of the carotid artery,” he announces. He cuts a short lengthwise slit in the man’s neck. Because no blood flows, it is easy to watch, easy to think of the action as simply something a man does on his job, like cutting roofing material or slicing foam core, rather than what it would more normally be: murder. Now the neck has a secret pocket, and Theo slips his finger into it. After some probing, he finds and raises the artery, which is then severed with a blade. The loose end is pink and rubbery and looks very much like what you blow into to inflate a whoopee cushion.

A cannula is inserted into the artery and connected by a length of tubing to the canister of embalming fluid. Mack starts the pump.

Here is where it all begins to make sense. Within minutes, the man’s face looks rejuvenated. The embalming fluid has rehydrated his tissues, filling out his sunken cheeks, his lined skin. His skin is pink now (the embalming fluid contains red coloring), no longer slack and papery. He looks healthy and surprisingly alive. This is why you don’t just stick bodies in the refrigerator before an open‑casket funeral.

Mack is telling me about a ninety‑seven‑year‑old woman who looked sixty after her embalming. “We had to paint in wrinkles, or the family wouldn’t recognize her.”

As hale and youthful as our Mr. Blank looks this morning, he will still eventually decompose. Mortuary embalming is designed to keep a cadaver looking fresh and uncadaverous for the funeral service, but not much longer. (Anatomy departments amp up the process by using greater amounts and higher concentrations of formalin; these corpses may remain intact for years, though they take on a kind of pickled horror‑movie appearance.) “As soon as the water table comes up, and the coffin gets wet,” Mack allows, “you’re going to have the same kind of decomposition you would have had if you hadn’t done embalming.” Water reverses the chemical reactions of embalming, he says.

Funeral homes sell sealed vaults designed to keep air and water out, but even then, the corpse’s prospects for eternal comeliness are iffy. The body may contain bacteria spores, hardy suspended‑animation DNA pods, able to withstand extremes of temperature, dryness, and chemical abuse, including that of embalming. Eventually the formaldehyde breaks down, and the coast is clear for the spores to bring forth bacteria.

“Undertakers used to claim embalming was permanent,” says Mack. “If it meant making the sale on that family, believe me, that embalmer was going to say anything,” agrees Thomas Chambers, of the W. W. Chambers chain of funeral homes, whose grandfather walked the boundaries of taste when he distributed promotional calendars featuring a nude silhouette of a shapely woman above the mortuary’s slogan, “Beautiful Bodies by Chambers.” (The woman was not, as Jessica Mitford seemed to hint in The American Way of Death , a cadaver that the mortuary had embalmed; that would have been going too far, even for Grandpa Chambers.)

Embalming fluid companies used to encourage experimentation by sponsoring best‑preserved‑body contests. The hope was that some undertaker, by craft or serendipity, would figure out the perfect balance of preservatives and hydrators, enabling his trade to preserve a body for years without mummifying it. Contestants were invited to submit photographs of decedents who had held up particularly well, along with a write‑up of their formulas and methods. The winning entries and photos would be published in mortuary trade journals, on the pre‑Jessica Mitford assumption that no one outside the business ever cracked an issue of Casket and Sunnyside .

I asked Mack what made the undertakers back off from their claims of eternal preservation. It was, as it so often is, a lawsuit. “One man took them up on it. He bought a space in a mausoleum and every six months he’d go in with his lunch and open up his mother’s casket and visit with her on his lunch hour. One especially wet spring, some moisture got in, and come to find, Mom had grown a beard. She was covered with mold.

He sued, and collected twenty‑five thousand dollars from the mortuary.

So they’ve stopped making that statement.” Further discouragement has come from the Federal Trade Commission, whose 1982 Funeral Rule prohibited mortuary professionals from claiming that the coffins they sold provided eternal protection against decay.

And that is embalming. It will make a good‑looking corpse of you for your funeral, but it will not keep you from one day dissolving and reeking, from becoming a Halloween ghoul. It is a temporary preservative, like the nitrites in your sausages. Eventually any meat, regardless of what you do to it, will wither and go off.

The point is that no matter what you choose to do with your body when you die, it won’t, ultimately, be very appealing. If you are inclined to donate yourself to science, you should not let images of dissection or dismemberment put you off. They are no more or less gruesome, in my opinion, than ordinary decay or the sewing shut of your jaws via your nostrils for a funeral viewing. Even cremation, when you get right down to it–as W.E.D. Evans, former Senior Lecturer in Morbid Anatomy at the University of London, did in his 1963 book The Chemistry of Death –isn’t a pretty event:

The skin and hair at once scorch, char and burn. Heat coagulation of muscle protein may become evident at this stage, causing the muscles slowly to contract, and there may be a steady divarication of the thighs with gradually developing flexion of the limbs. There is a popular idea that early in the cremation process the heat causes the trunk to flex forwards violently so that the body suddenly “sits up,” bursting open the lid of the coffin, but this has not been observed personally….

Occasionally there is swelling of the abdomen before the skin and abdominal muscles char and split; the swelling is due to formation of steam and the expansion of gases in the abdominal contents.

Destruction of the soft tissues gradually exposes parts of the skeleton. The skull is soon devoid of covering, then the bones of the limbs appear…. The abdominal contents burn fairly slowly, and the lungs more slowly still. It has been observed that the brain is specially resistant to complete combustion during cremation of the body. Even when the vault of the skull has broken and fallen away, the brain has been seen as a dark, fused mass with a rather sticky consistency…. Eventually the spine becomes visible as the viscera disappear, the bones glow whitely in the flames and the skeleton falls apart.

Drops of sweat bead the inside surface of Nicole’s splash shield. We’ve been here more than an hour. It’s almost over. Theo looks at Mack. “Will we be suturing the anus?” He turns to me. “Otherwise leakage can wick into the funeral clothing and it’s an awful mess.”

I don’t mind Theo’s matter‑of‑factness. Life contains these things: leakage and wickage and discharge, pus and snot and slime and gleet. We are biology. We are reminded of this at the beginning and the end, at birth and at death. In between we do what we can to forget.

Since our decedent will not be having a funeral service, it is up to Mack whether the students must take the final step. He decides to let it go.

Unless the visitor wishes to see it. They look at me.

“No thank you.” Enough biology for today.

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1609;