Bristol Stool Chart

I T IS A standard party invitation in most respects. There’s a street map of the neighborhood, the address and time of the party, and some friendly encouragement to bring the whole family. The decorative elements, though, are unusual: a cutaway illustration of the interior of the human colon, its parts neatly labeled. Above this, in a festive typeface, it says, “Gut Microflora Party!” The host is Alexander Khoruts, a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. Along with the usual complement of colonoscopies and dyspepsia consults, he performs transplants of colon bacteria–aka gut microflora.

Almost everyone gathered at the party this evening is involved with this work. There is Mike Sadowsky, coeditor of the textbook The Fecal Bacteria and Khoruts’s research partner. Leaning into the buffet is Matt Hamilton, a University of Minnesota postdoc student who prepares the matter for transplant. Matt is spooning Khoruts’s homemade Russian red beet salad onto a plate, enough of it that a nurse tells him he’s going to “look like a GI bleed” tomorrow.

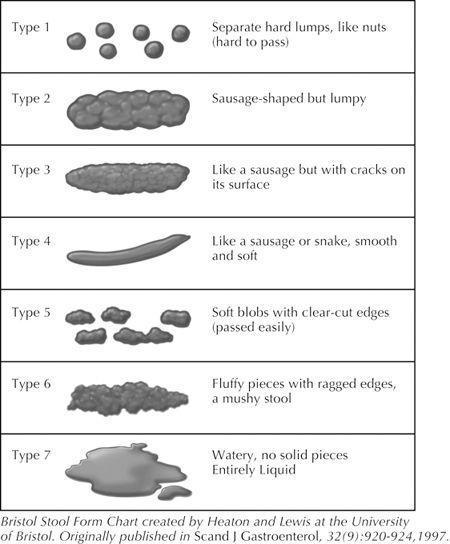

The nurse admires a platter of chocolate‑covered whole bananas, one of the thematically appropriate desserts created by Khoruts’s thirteen‑year‑old. James is very much his father’s son, intelligent and cultured, with a sly sense of humor. He plays classical music on the grand piano in the living room and would like to write novels one day. The nurse asks James what number the desserts[118]would be on the Bristol Stool Scale. He replies without hesitating–4 (“like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft”).

It’s tough to find an inappropriate mealtime conversation with this group–not because they’re crass or ill‑mannered, but because they view the universe of the colon very differently than the rest of us do. The interactions between the human body and its gut microbiome–as our hundred trillion intestinal roomers are collectively known–is a hot research area of late. For decades, medical investigators have looked at the role of food and nutrients in disease treatment and prevention. That has begun to seem simplistic. Now the goal is to tease apart the interactions between the body, the food, and the bacteria that break down the food. One example is the cancer‑fighter du jour: the polyphenol family, found in coffee, tea, fruits, and vegetables. Some of the most beneficial polyphenols aren’t absorbed in the small intestine; we depend on colonic bacteria to metabolize them. Depending on who’s living in your gut, you may or may not benefit from what you eat. Or be harmed. Charred red meat has long been called a carcinogen, but in fact it is only the raw material for making carcinogens. Without the gut bacteria that break it down, the raw goods are harmless. (This applies to drugs too; depending on the makeup of your gut flora, the efficacy of a drug may vary.) The science is new and extremely complex, but the bottom line is simple. Changing people’s bacteria is turning out to be a more effective strategy for treatment and prevention of disease than changing their diet.

As a member of a culture that demonizes bacteria in general and the germs of other people in specific, you may find it disturbing to imagine checking into a hospital to be implanted with bacteria from another person’s colon. For the patient I’ll shortly be meeting, a man invaded by Clostridium difficile , it’s a welcome event. Infection with chronic C. diff –to use the medical nickname–can be an incapacitating and sometimes fatal illness.

“When you’re fifty‑five years old and you’re wearing diapers that you’re changing ten times a day,” Matt Hamilton says, “you’re numb to the ick factor.” He lifts some stuffed tomatoes to his plate. Matt has the forceful, unabashed appetite of the big, young male.

“For the patient, there is no ick factor,” Khoruts adds. “They’ve been icked out. It’s a chronic disease and they just want to be rid of it.”

As regards bacteria in general, a radical shift in thinking is under way. For starters, there are way more of them than you. For every one cell of your body, there are nine (smaller) cells of bacteria. Khoruts takes issue with the them‑versus‑you mentality. “Bacteria represent a metabolically active organ in our bodies.” They are you. You are them. “It’s a philosophical question. Who owns who?”

People’s bacterial demographics are likely to influence their day‑to‑day behavior. “Certain populations in the gut may want you to eat a certain kind of diet or to store energy differently.” (A clinical trial is under way in the Netherlands to see if transplants of “donor feces” from lean volunteers will help subjects lose weight;[119]thus far results are encouraging but undramatic.) Khoruts gave me a memorable example of how behavior can be covertly manipulated by microorganisms. The parasite Toxoplasma infects rats but needs to make its way into a cat’s gut to reproduce. The parasite’s strategy for achieving this goal is to alter the rat brain such that the rodent is now attracted to cat urine. Rat walks right up to cat, gets killed, eaten. If you saw the events unfold, Khoruts continued, you’d scratch your head and go, What is wrong with that rat? Then he smiled. “Do you think Republicans have different flora?”

What determines your internal cast of characters? For the most part, it’s luck of the draw. The bacteria species in your colon today are more or less the same ones you had when you were six months old. About 80 percent of a person’s gut microflora transmit from his or her mother during birth. “It’s a very stable system,” says Khoruts. “You can trace a person’s family tree by their flora.”

The party is winding down. I go into the kitchen to say good night to James and to Khoruts’s mirthful, tolerant girlfriend, Katerina. A blender sits on the counter by the sink, waiting to be washed. “Hey,” says James. “You missed the chocolate poop smoothies.”

That’s okay, because I’ll be seeing the real thing.

• • •

L IKE ANY TRANSPLANT, it begins with a donor. “Anyone’s will do,” says Khoruts. He has no idea which bacteria he’s after–which are the avenging angels that bring C. diff under control. Even if he knew, there’s no simple way to determine whether those species are present in a donor’s contribution. Most species of fecal bacteria are tough to culture in the lab because they’re anaerobic, meaning they can’t live in the presence of oxygen. (Common strains of E. coli and Staph bacteria are exceptions. They thrive inside people and out, on doctors and their equipment, and everywhere in between.)

The only thing Khoruts requires of donors is that they be free of digestive maladies and communicable diseases. Family members are not the most desirable donors because their medical questionnaire may not be entirely truthful. “You wouldn’t necessarily want to reveal to your loved ones that you’ve been visiting prostitutes.” Khoruts is partial to the donations of a local man who, understandably, wishes to remain anonymous. This man’s bacteria have been transplanted into ten patients, curing all of them. “His head is getting bigger,” deadpans Khoruts. Most of what Khoruts says is delivered deadpan. “In Russia,” he told me, “if you smile a lot, they think something’s wrong with you.” He has to remind himself to smile when he talks to people. Sometimes it arrives a beat or two late, like the words of a far‑flung foreign correspondent reporting live on TV.

“Here he is.” A tall man, dressed for a Minneapolis winter, lopes down the hallway carrying a small paper bag.

“Not my best work,” the man says, nodding hello to me as he hands Khoruts the bag. With no further chitchat, he turns to leave. He does not seem embarrassed, just pressed for time. He’s an unlikely hero, quietly saving lives and restoring health with the product of his morning toilet.

Khoruts slips into an empty exam room and dials Matt Hamilton’s number. On the morning of a transplant, Matt will stop by the hospital on his way to the Environmental Microbiology Laboratory, where he works and the material is processed. He’s usually here by now, and Khoruts is feeling antsy. Anaerobic bacteria outside the colon have a limited life span. No one knows how many hours they can survive.

Khoruts leaves a message: “Hi, it’s Alex. The stuff is ready for pickup.” He squints. “I think that’s his number.” It would be a provocative message to receive from a stranger. I picture narcotics officers storming the gastroenterology department, Khoruts struggling to explain.

Khoruts has barely hung up when Matt hustles in, all polar fleece and apology. Matt smiles as naturally as Khoruts doesn’t. I imagine it is almost impossible to be peeved at Matt Hamilton.

The lab is ten minutes by car. Because Matt is driving fast and the cooler keeps threatening to slide off the backseat, there’s a mild tension in the car. The cooler is a tangible presence, somewhere between groceries and an actual passenger. Soon we’re circling, looking for parking. Matt resents the waste of time. “If I had organs, they’d give me a parking pass.”

The parking turns out to take longer than the processing. The equipment is simple: an Oster[120]blender and a set of soil sieves. The blender lid has been rigged with two tubes so that nitrogen can be pumped in and oxygen forced out. Two or three 20‑second pulses on the liquefy setting typically does the trick, and then it’s on to the sieves. For obvious reasons, everything is done under a fume hood. Matt chats as he sieves, occasionally calling out a recognizable element: a chili flake, a piece of peanut.[121]

A decision is made to do a second run through the blender. If the material doesn’t flow freely, it can clog the colonoscope and compromise the microbes’ spread through the colon. He turns to face me. “So today we’ve kind of been confronted with what to do when it’s a hard, solid chunk rather than an easier mix.” It’s like American Chopper when Paul Sr. or Vinnie addresses the camera to give a summary of what viewers have been seeing.

Finally the liquid is poured into a container with a very good seal and returned to the cooler. It looks like coffee with low‑fat milk. There is almost no smell, the gases having all gone up the fume hood. The three of us, Matt and I and The Cooler, hurry back to the car and retrace our route to the hospital.

The transplant patient has arrived. He waits on a gurney in a room made by curtains. Khoruts is in the hallway in his white coat. Matt hands him the cooler. He fills and caps four vials that will be pumped into the patient through the colonoscope. For now, they are laid on ice in a plastic bowl. Khoruts asks a passing nurse where he can leave the bowl while he waits for an exam room to open up. She glances at it, barely breaking stride. “Just don’t bring it in the break room.”

L IKE PEOPLE, BACTERIA are good or bad not so much by nature as by circumstance. Staph bacteria are relatively mellow on the skin, presumably because there are fewer nutrients there. Should they manage to make their way into the bloodstream via, for instance, a surgical incision, it’s a different story. Receptors and surface proteins allow bacteria to “sense” nutrients in their environment. As Matt puts it, “They’re like: ‘This is a good spot, we should go crazy in here.’” Gut microflora party! Bad news for the host. Strains found in hospitals are more likely to be antibiotic‑resistant, and hospital patients are often immunocompromised and can’t fight back.

Likewise E. coli . Most strains cause no symptoms inside the colon. The immune system is accustomed to huge numbers of them in the gut. No cause for alarm. Should the same strain make its way to the urethra and bladder, now it’s perceived as an invader. In this case, the immune attack itself creates the symptoms–in the form, say, of inflammation.

Even C. difficile is not inherently bad. Thirty to fifty percent of infants are colonized with C. diff and suffer no ill effects. Three percent of adults are known to harbor it in their gut without problems. Other bacteria may tell it not to make toxins, or the numbers are too small for the toxins to create noticeable symptoms.

The problems often begin when a colon is wiped clean by antibiotics. Now C. diff has a chance to gain a foothold. As careful as hospitals try to be, C. diff spores are everywhere. And certain conditions in the colon make it easier for C. diff to thrive. Diverticuli are pockets along the colon wall, often created by chronic constipation. Like this: If the muscles of the colon have to push hard to move waste along and there’s a weak spot in the wall, the matter will follow the path of least resistance. The weak spot will balloon outward and form a small pocket. C. diff spores seed the pockets.

Eighty percent of the time, antibiotics clear up a C. diff infection. Twenty percent of the time, it comes back within a week or two. The C. diff entrenched in diverticuli are tough to annihilate; they’re the Al Qaeda of the GI tract, hiding out in inaccessible caves. “Antibiotics are a double‑edged sword,” says Khoruts. “They suppress C. diff , but they also kill the bacteria that keep it under control.” Every time the patient has a relapse, the chance of another relapse doubles. Infections with C. diff kill around sixteen thousand Americans a year.

Today’s patient has diverticuli that became abscessed. Multiple severe bouts of colitis have caused diarrhea so severe he has had, at times, to be fed intravenously. You wouldn’t guess any of this to look at him now, in the exam room. He has been given Versed, an antianxiety medication. He lies calmly on his side in a blue and white johnny with no pants. There is a heartbreaking vulnerability to people having hospital procedures. They may be CEOs or generals on the outside, but in here they are just patients, docile, hopeful, grateful.

The lights are dim and a stereo plays classical music. Khoruts makes conversation to gauge the sedative’s effects. He’s listening for a quieting of the voice, a slowing of words. “Do you have any pets?”

The room is quiet for a moment. “…pets.”

“I think we’re ready to go.”

A nurse brings the bowl with the vials. I ask her if the red color of the caps on the vials signifies biohazard.

“No, just the brown color inside.”

Unless one is watching closely, a fecal transplant looks very much like a colonoscopy. The first thing to appear on the video monitor is a careering fish‑eye view of the exam room as the scope is pulled from its holder and carried over to the bed. If you are young enough to be unfamiliar with a colonoscope, I invite you to picture a bartender’s soda gun: the long, flexible black tube, the controls mounted on a handheld head. Where the bartender has buttons for soda water and cola, Khoruts can choose between carbon dioxide, for inflating the colon so he can see it better, and saline, for rinsing away remnants of an “inadequate prep.”

Khoruts works the control buttons with his left hand, torquing the tube with his right. I comment that it’s like playing an accordion or a piano, both arms working independently at unrelated tasks. Khoruts, who plays piano in addition to colonoscope, prefers the analogy of the amputee’s prosthesis. “Over time it becomes part of your body. Even though I don’t have nerve endings there, I kind of know what’s happening.”

We’re in now, heading north. The man’s heartbeat is visible as a quiver in the colon wall. Khoruts maneuvers a crook. Shifting a patient’s position can help unkink a sharp turn, so the nurse leans in hard, like a driver pushing a stall to the shoulder of the road.

Using a plunger on the control head, Khoruts releases a portion of the transplant material. Since the colon has been wiped clean beforehand with antibiotics, the unicellular arrivals won’t have to battle a lot of natives. However many survived the antibiotic, the immigrants are sure to prevail. Within two weeks, Khoruts’s research shows, the microbial profiles of donor and recipient colons are synced.

One more release, at the far end of the colon, and Khoruts retracts the scope.

A couple days later, Khoruts forwards an e‑mail from the patient (with surname deleted). The pain and diarrhea that had kept him from going to work for a year were gone. “I had,” he wrote, “a small solid bowel movement on Saturday evening.” It may not be your idea of an exciting Saturday evening, but for Mr. F., it was tough to top.

• • •

T HE FIRST FECAL transplant was performed in 1958, by a surgeon named Ben Eiseman. In the early days of antibiotics, patients frequently developed diarrhea from the massive kill‑off of normal bacteria. Eiseman thought it might be helpful to restock the gut with someone else’s normals. “Those were the days when if we had an idea,” says Eiseman, ninety‑three and living in Denver at the time I wrote him, “we simply tried it.”

Rarely does medical science come up with a treatment so effective, inexpensive, and free of side effects. As I write this, Khoruts has done forty transplants to treat intractable C. diff infection, with a success rate of 93 percent. In a University of Alberta study published in 2012, 103 out of 124 fecal transplants resulted in immediate improvement. It’s been fifty‑five years since Eiseman first pushed the plunger, yet no U.S. insurance company formally recognizes the procedure.

Why? Has the “ick factor” hampered the procedure’s acceptance? Partly, says Khoruts. “There is a natural revulsion. It just doesn’t seem right.” He thinks it has more to do with the process by which a new medical procedure goes from experimental to mainstream. A year after I visited, the major gastroenterology and infectious disease societies invited “a little band of fecal transplant practitioners” to put together a “best practice” paper outlining optimal procedures: a common first step toward establishing codes for billing for the procedure and making the case for insurance companies to cover it. As of mid‑2012, there was no billing code or agreed‑upon fee. Khoruts estimates the process will take one to two years more. In the meantime, he simply bills for a colonoscopy.

The extent to which health care bureaucracy stands in the way of better patient care is occasionally astounding. It took a year and a half for Khoruts’s study on bacteriotherapy for recurrent C. diff infection to be approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board (IRB)–which oversees the safety of study subjects–even though the board had no substantive criticisms or concerns. The morning I visited to see the transplant, Khoruts showed me an object I wasn’t familiar with, a winged plastic bowl called a toilet hat[122]that fits over the rim of the bowl to catch the donor’s produce. “That caused about two months of delay on the IRB protocol,” he said. “They sent it back saying, ‘Who’s going to pay for the toilet hats?’ They’re fifty cents apiece.”

Khoruts has also been working on a proposal for a study to evaluate fecal transplants for treating ulcerative colitis.[123]Inflammatory bowel diseases–irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease–are thought to be caused by an inappropriate immune response to normal bacteria; the colon gets caught in the cross fire. This time around, the IRB refused to approve the trial until the FDA had approved it. And that’s just for the trial. Final FDA approval, the kind that makes the procedure available to anyone, is a costly process that can take upward of a decade.

And in the case of fecal transplants, there’s no drug or medical device involved, and thus no pharmaceutical company or device maker with diverticuli deep enough to fund the multiple rounds of controlled clinical trials. If anything, drug companies might be inclined to fight the procedure’s approval. Pharmaceutical companies make money by treating diseases, not by curing them. “There’s billions of dollars at stake,” says Khoruts. “I told Katerina, if this works, don’t be surprised to find me at the bottom of the river.”

We are sitting in Khoruts’s office, in between colonoscopies. Above our heads, on a shelf, is a lurid plastic life‑size model of a human rectum afflicted by every imaginable malady: hemorrhoid, fistula, ulcerative colitis, fecaliths. Metaphor for the U.S. health care system?

Khoruts smiles. “Bookend.” A drug company was giving them away at Digestive Disease Week, an annual convention of gastroenterologists and drug reps, with the occasional person dressed as a stomach, handing out samples.

While the bureaucracy inches forward, fecal transplants for C. diff are quietly carried out in hospitals in thirty states. But that leaves twenty where patients have no access. Some have turned to what a researcher in one Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology paper called “self‑administered home fecal transplantation.” Though seven of seven C. diff sufferers were cured by self‑ or “family‑administered” transplants using a drugstore enema kit, it doesn’t always go well. One woman who recently e‑mailed Khoruts for advice didn’t follow directions. She put tap water in the blender, and the chlorine killed the bacteria. Another in‑home transplant replaced one source of diarrhea with another: fecal parasites contracted from the donor. Rather than protecting patients, IRBs–with their delays and prodigious paperwork–can put them in harm’s way.

Fecal bacteriotherapy will quickly become more streamlined. More sophisticated filtration will enable the separation of cellular material from ick. The bacteria can then be dosed with cryoprotectant–to prevent ice crystals from puncturing the cells–frozen, and shipped where it’s needed, when it’s needed. Khoruts’s operation is already headed this way.

The Holy Grail would be a simple pill, along the lines of the lactobacillus suppositories used to cure recurrent yeast infection. Generally and unfortunately, aerobic strains that are easy to grow and keep alive in the oxygen environment of a lab are unlikely to be the beneficial ones. Though researchers don’t know exactly which bacteria are the desirables, they do know they’re likely to be anaerobic species that thrive only within the colon. You want the creatures that are dependent on a healthy you for their own survival, the ones whose evolutionary mission is aligned with your own–your microscopic partners in health.

I asked Khoruts what exactly is in the “probiotic” products seen in stores now. “Marketing,” he replied. Microbiologist Gregor Reid, director of the Canadian Research & Development Centre for Probiotics, seconds the sentiment. With one exception, the bacteria (if they even exist) in probiotics are aerobic; culturing, processing, and shipping bacteria in an oxygen‑free environment is complicated and costly. Ninety‑five percent of these products, Reid told me, “have never been tested in a human and should not be called probiotic.”

I PREDICT THAT ONE way or another, within a decade, everyone will know someone who’s benefited from a dose of someone else’s body products. I recently received an e‑mail from a doctor in Texas, telling me the story of Lloyd Storr, a Lubbock physician who treated chronic ear infections via homemade “earwax transfusions”: drops of donor earwax boiled up in glycerin. Earwax maintains an acid environment that discourages bacterial overgrowth and possibly contains some antibacterial chemicals. Whatever it does, some people’s works better than others’. Khoruts has been encouraging a friend of his, a periodontist, to try bacterial transplantation[124]as a treatment for gum disease.

If things go as they should, the bacteria hysteria so lucratively nurtured by the likes of Purell and Lysol will begin to subside. Thanks to the courageous blender‑wielding pioneers of bacterial transplantation, fussiness and unfounded fear will be buffered by rational thinking and perhaps even a modicum of gratitude.

A tip of the toilet hat to you, Alexander Khoruts.

T HE GREAT IRONY is that in the beginning, the gut was all there was. “We’re basically a highly evolved earthworm surrounding the intestinal tract,” Khoruts commented as we drove away from his clinic the last day I was there. Eventually, the food processor had to have a brain attached to help it look for food, and limbs to reach that food. That increased its size, so it needed a circulatory system to distribute the fuel that powered the limbs. And so on. Even now, the digestive tract has its own immune system and its own primitive brain, the so‑called enteric nervous system. I recalled what Ton van Vliet had said at one point in our conversation: “People are surprised to learn: They are a big pipe with a little bit around it.”

You are what you eat, but more than that, you are how you eat. Be thankful you’re not a sea anemone, disgorging lunch through the same hole that dinner goes in. Be glad you’re not a grazer or a cud chewer, spending your life stoking the furnace. Be thankful for digestive juices and enzymes, for villi, for fire and cooking, all the miracles that have made us what we are. Khoruts gave the example of the gorilla, a fellow ape held back by the energy demands of a less streamlined gut. Like the cow, the gorilla lives by fermenting vast quantities of crude vegetation. “He’s processing leaves all day. Just sitting and chewing, and cooking inside. There’s no room for great thoughts.”

Those who know the human gut intimately see beauty, not only in its sophistication but in its inner landscapes and architecture. In a 1998 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine , two Spanish physicians published a pair of photographs: “the haustrations of the transverse colon” side by side with the arches of an upper‑floor arcade in Gaudi’s La Pedrera. Inspired, wanting to see my own internal Gaudi, I had my first colonoscopy without drugs.[125]

There is an unnameable feeling I’ve had maybe ten times in my life. It is a mix of wonder, privilege, humility. An awe that borders on fear. I’ve felt it in a field of snow on the outskirts of Fairbanks, Alaska, with the northern lights whipping overhead so seemingly close I dropped to my knees. I am walloped by it on dark nights in the mountains, looking up at the sparkling smear of our galaxy. Laying eyes on my own ileocecal valve, peering into my appendix from within, bearing witness to the magnificent complexity of the human body, I felt, let’s be honest, mild to moderate cramping. But you understand what I’m getting at here. Most of us pass our lives never once laying eyes on our organs, the most precious and amazing things we own. Until something goes wrong, we barely give them thought. This seems strange to me. How is it that we find Christina Aguilera more interesting than the inside of our own bodies? It is, of course, possible that I seem strange. You may be thinking, Wow, that Mary Roach has her head up her ass. To which I say: Only briefly, and with the utmost respect.

[1]Similar products exist to this day, under names like “Dual Sex Human Torso with Detachable Head” and “Deluxe 16‑Part Human Torso,” adding an illicit serial‑killer, sex‑crime thrill to educational supply catalogues.

[2]In reality, guts are more stew than meat counter, a fact that went underappreciated for centuries. So great was the Victorian taste for order that displaced organs constituted a medical diagnosis. Doctors had been misled not by plastic models, but by cadavers and surgical patients–whose organs ride higher because the body is horizontal. The debut of X‑rays, for which patients sit up and guts slosh downward, spawned a fad for surgery on “dropped organs”–hundreds of body parts needlessly hitched up and sewn in place.

[3]The Hair , by Charles Henri Leonard, published in 1879. It was from Leonard that I learned of a framed display of presidential hair, currently residing in the National Museum of American History and featuring snippets from the first fourteen presidents, including a coarse, yellow‑gray, “somewhat peculiar” lock from John Quincy Adams. Leonard, himself moderately peculiar, calculated that “a single head of hair of average growth and luxuriousness in any audience of two hundred people will hold supported that entire audience” and, I would add, render an evening at the theater so much the more memorable.

[4]A few words on sniffing. Without it (or a Harley), you miss all but the most potent of smells going on around you. Only 5 to 10 percent of air inhaled while breathing normally reaches the olfactory epithelium, at the roof of the nasal cavity.researchers in need of a controlled, consistently sized sniff use an olfactometer to deliver “odorant pulses.” The technique replaces the rather more vigorous “blast olfactometry” as well as the original olfactometer, which connected to a glass and aluminum box called the “camera inodorata.” (“The subject’s head was placed in the box,” wrote the inventor, alarmingly, in 1921.)

[5]An Internet search on the medical term for nostrils produced this: “Save on Nasal Nares! Free 2‑day Shipping with Amazon Prime.” They really are taking over the world.

[6]“Skunky” is between “rotten egg” and “canned corn” on the Defects Wheel for Beer. (Langstaff designed diagnostic wheels for off‑flavors in wine, beer, and olive oil.) In the absence of skunks, a mild rendition of skunkiness is achieved by oxidating beer, that is, exposing it to air, as by spilling it or leaving out half‑filled glasses.

[7]In 2010, inventor George Eapen and snack‑food giant Frito‑Lay took the comparison beyond the realm of metaphor. They patented a system whereby snack‑food bags could be printed with a bar code allowing consumers to retrieve and download a fifteen‑second audio clip of a symphonic interlude, with the different instruments representing the various flavor components. Eapen, in his patent, used the example of a salsa‑flavored corn chip. “A piano intro begins upon the customer’s perception of the cilantro flavoring…. The full band section occurs at approximately the time that the consumer perceives the tomatillo and lime flavors…. A second melody section corresponds to the sensation of the heat burn imparted by the Serrano chili.” U.S. Patent No. 7,942,311 includes sheet music for the salsa‑flavored chip experience.

[8]It could be worse. In 1984, goat‑milk flavor panelists were enlisted by a team of Pennsylvania ag researchers to sleuth the source of a nasty “goaty” flavor that intermittently fouls goat milk. The main suspect was a noxious odor from the scent glands of amorous male goats. But there was also this: “The buck in rut sprays urine over its chin and neck area.” Five pungent compounds isolated from the urine and scent glands of rutting males were added, one at a time, to samples of pure, sweet goat milk. The panelists rated each sample for “goaty” “rancid,” and “musky‑melon” flavors. Simple answers proved elusive. “A thorough investigation of ‘goaty’ flavor,” the researchers concluded, “is beyond the scope of this paper.”

[9]Probably more. The Handbook of Fruit and Vegetable Flavors includes a four‑page table of aroma compounds identified in fresh pineapple: 716 chemicals in all.

[10]Moeller, who has tasted the naked Cheeto, likens it to a piece of unsweetened puffed corn cereal.

[11]Or that’s what we think we like. In reality, the average person eats no more than about thirty foods on a regular basis. “It’s very restricted,” says Adam Drewnowski, director of the University of Washington Center for Obesity Research, who did the tallying. Most people ran through their entire repertoire in four days.

[12]This explains the perplexing odor of swamp water on certain floors of the Monell Chemical Senses Center during the 1980s. The basement was a big catfish pond.

[13]Not a Campbell’s product.

[14]Gone are the colored pet‑food pieces of the early 1990s. “Because when it comes back up, then you have green and red dye all over your carpet,” says Rawson. “That was a huge duh .”

[15]My brother works in market research. One time after he visited I found a thick report in the trash detailing consumers’ feelings about pre‑moistened towelettes. It contained the term “wiping events.”

[16]The Holy Grail is a pet food that not only smells unobjectionable, but also makes the pets’ feces smell unobjectionable. It’s a challenge because most things you could add to do that will get broken down in digestion and rendered ineffectual. Activated charcoal is problematic because it binds up not just smelly compounds, but nutrients too. Hill’s Pet Nutrition experimented with adding ginger. It worked well enough for a patent to have been granted, which must have been some consolation to the nine human panelists tasked with “detecting differences in intensity of the stool odor by sniffing the odor through a port.”

[17]As is jalapeño–though according to psychologist Paul Rozin, Mexican dogs, unlike American dogs, enjoy a little heat. Rozin’s work suggests animals have cultural food preferences too. Rozin was not the first academic to feed ethnic cuisine to research animals. In “The Effect of a Native Mexican Diet on Learning and Reasoning in White Rats,” subjects were served chili con carne, boiled pinto beans, and black coffee. Their scores at maze‑solving remained high, possibly because of an added impetus to find their way to a bathroom. In 1926, the Indian Research Fund Association compared rats who lived on chapatis and vegetables with rats fed a Western diet of tinned meat, white bread, jam, and tea. So repellent was the Western fare that the latter group preferred to eat their cage mates, three of them so completely that “little or nothing remained for post‑mortem examination.”

[18]The Inuit Games. Most are indoor competitions originally designed to fit in igloos. Example: the Ear Lift: “On a signal, the competitor walks forward lifting the weight off the floor and carrying it with his ear for as far a distance as his ear will allow.” For the Mouth Pull, opponents stand side by side, shoulders touching and arms around each other’s necks as if they were dearest friends. Each grabs the outside corner of his opponent’s mouth with his middle finger and attempts to pull him over a line drawn in the snow between them. As so often is the case in life, “strongest mouth wins.”

[19]Among themselves, meat professionals speak a jolly slang. “Plucks” are thoracic viscera: heart, lungs, trachea. Spleens are “melts,” rumens are “paunch,” and unborn calves are “slunks.” I once saw a cardboard box outside a New York meat district warehouse with a crude sign taped to it: FLAPS AND TRIANGLES.

[20]The children were wise to be wary. Compulsive hair‑eaters wind up with trichobezoars–human hairballs. The biggest ones extend from stomach into intestine and look like otters or big hairy turds and require removal by stunned surgeons who run for their cameras and publish the pictures in medical journal articles about “Rapunzel syndrome.” Bonus points for reading this footnote on April 27, National Hairball Awareness Day.

[21]Meat and patriotism do not fit naturally together, and sloganeering proved a challenge. The motto “Food Fights for Freedom” would seem to inspire cafeteria mayhem more than personal sacrifice.

[22]Pledge madness peaked in 1942. The June issue of Practical Home Economics reprinted a twenty‑item Alhambra, California, Student Council antiwaste pledge that included a promise to “drive carefully to conserve rubber” and another to “get to class on time to save paper on tardy slips.” Perhaps more dire than the shortages in metal, meat, paper, and rubber was the “boy shortage” mentioned in an advice column on the same page. “Unless you do something about it, this means empty hours galore!” Luckily, the magazine had some suggestions. An out‑of‑fashion bouclé suit could be “unraveled, washed, tinted and reknitted” to make baby clothes. Still bored? “Take two worn rayon dresses and combine them to make one Sunday‑best that looks brand new”–and fits like a dream if you are a giant insect or person with four arms.

[23]They are to be excused for not tasting it too. Amniotic fluid contains fetal urine (from swallowed amniotic fluid) and occasionally meconium: baby’s first feces, composed of mucus, bile, epithelial cells, shed fetal hair, and other amniotic detritus. The Wikipedia entry helpfully contrasts the tarry, olive‑brown smear of meconium–photographed in a tiny disposable diaper–with the similarly posed yellowish excretion of a breast‑fed newborn, both with an option for viewing in the magnified resolution of 1,280 × 528 pixels.

[24]Bull was chief of the University of Illinois Meats Division and founding patron of the Sleeter Bull Undergraduate Meats Award. Along with meat scholarship, Bull supported and served as grand registrar of the Alpha Gamma Rho fraternity, where they knew a thing or two about undergraduate meats.

[25]The other common source of L‑cysteine is feathers. Blech has a theory that this might explain the medicinal value of chicken soup, a recipe for which can be found in the Gemorah (shabbos 145b) portion of the Talmud. L‑cysteine, he says, is similar to the mucus‑thinning drug acetylcysteine. And it is found, albeit in lesser amounts, in birds’ skin. “Chicken soup and its L‑cysteine,” Blech said merrily, may indeed be “just what the doctor ordered.”

[26]He did, however, leave the residue of his estate to Harvard, part of which went toward funding the Horace Fletcher Prize. This was to be awarded each year for “the best thesis on the subject ‘Special Uses of Circumvallate Papilli and the Saliva of the Mouth in Regulating Physiological Economy in Nutrition.’” Harvard’s Prize Office has no record of anyone applying for, much less winning, the prize.

[27]The two parted ways over feces. Kellogg’s healthful ideal was four loose logs a day; Fletcher’s was a few dry balls once a week. It got personal. “His tongue was heavily coated and his breath was highly malodorous,” sniped Kellogg.

[28]I managed to track down only one stanza. It was enough. “I choose to chew / because I wish to do / the sort of thing that Nature had in view / Before bad cooks invented sav’ry stew / When the only way to eat was to chew, chew, chew.”

[29]“Vesuvius is puking lava at an alarming rate.”

[30]A summary of Chittenden’s project appears in the June 1903 issue of Popular Science Monthly , on the same page as an account of the Havre Two‑Legged Horse, a foal born without forelegs, resembling a kangaroo “but with less to console it, since the latter has legs in front, which, while small and short are better than none at all.” On a more upbeat note, the foal was “very healthy and obtains its food from a goat.”

[31]“Put 2 and ½ pounds of guano with 3 qts of water in an enamel stew‑pan, boil for 3 or 4 hours, then let it cool. Separate the clear liquid, and about a quart of this healthy extract is obtained.” Use sparingly, cautions the author, or it “will be as repugnant as pepper or vinegar.”

[32]The human digestive tract is like the Amtrak line from Seattle to Los Angeles: transit time is about thirty hours, and the scenery on the last leg is pretty monotonous.

[33]“It can even vomit,” boasts its designer. No reply arrived in response to an e‑mail asking whether and into what the Model Gut excretes.

[34]More recently, the digestive action of a healthy adult male obliterated everything but 28 bones (out of 131) belonging to a segmented shrew swallowed without chewing. (Debunking Fletcher wasn’t the intent. The study served as a caution to archaeologists who draw conclusions about human and animal diets based on the skeletal remains of prey items.) The shrew, but not the person who ate it, was thanked in the acknowledgments, leading me to suspect that the paper’s lead author, Peter Stahl, had done the deed. He confirmed this, adding that it went down with the help of “a little bit of spaghetti sauce.”

[35]The Beaumont findings were pointed out to Fletcher in a discussion that followed a lecture of his at a 1909 dental convention in Rochester, New York. “It made no practical difference whether the food was previously masticated very thoroughly, or whether the morsel… was introduced… in one solid chunk,” said an audience member. Before Fletcher could reply, two more doctors chimed with opinions on this and that. By the time Fletcher spoke again, two pages farther into the transcript, the mention of Beaumont was either forgotten or conveniently ignored. At any rate, Fletcher didn’t address it.

[36]Using the tongue is less peculiar than it seems. Before doctors could ship patients’ bodily fluids off to labs for analysis, they sometimes relied on tongue and nose for diagnostic clues. Intensely sweet urine, for instance, indicates diabetes. Pus can be distinguished from mucus, wrote Dr. Samuel Cooper in his 1823 Dictionary of Practical Surgery, by its “sweetish mawkish” taste and a “smell peculiar to itself.” To the doctor who is still struggling with the distinction, perhaps because he has endeavored to learn surgery from a dictionary, Cooper offers this: “Pus sinks in water; mucus floats.”

[37]The shipping of bodily fluids was a trying business in the 1800s. One shipment to Europe took four months. Bottles would arrived “spilt” or “spoilt” or both. One correspondent, taking no chances, directed Beaumont to ship the secretions “in a Lynch & Clark’s pint Congress water bottle, carefully marked, sealed and capped with strong leather and twine, cased in tin, with the lid soldered on.”

[38]Except possibly Irwin Mandel. Mandel was the author of a hundred papers on saliva. A winner of the Salivary Research Award. The subject of a lush tribute in the Journal of Dental Research in 1997. The editor of the Journal of Dental Research in 1997. Mandel did not go so far as to write the tribute himself. That was done by B. J. Baum, P. C. Fox, and L. A. Tabak. Having three authors means no one man can be blamed for the sentence “Saliva was his vehicle and he went with the flow.”

[39]I can vouch for this. I once toured the refrigerator at Hill Top Research, where odor judges test the efficacy of deodorizing products like mouthwash and cat litter. The president at the time, Jack Wild, was looking for the malodor component of armpit smell, which I had asked to sample. He kept opening little jars, going, “Nope, that’s dirty feet, no, that’s fishy amines” (vaginal odor). I asked him which is the worst. “Incubated saliva,” he said without hesitating. “Both Thelma and I got dry heaves.” I don’t recall Thelma’s title. Whatever she did, she deserved a raise.

[40]Less high‑tech than it sounds. Subjects leaned over and spat into the machine every two minutes. A slight improvement over the earliest collection technique, circa 1935: “The subject sits with head tilted forward, allowing the saliva to run to the front of the mouth… and drip out between parted lips.” A photo in Kerr’s monograph shows a nicely dressed woman, hair bobbed, hands palm down on the table in front of her, forehead resting in a support. An enamel basin is positioned just so, to catch the drippings.

[41]But nothing compared to crow droppings. According to Harper, the traditional purification ritual for the Brahmin polluted by crow feces is “a thousand and one baths.” This has been rendered less onerous by the invention of the showerhead and the crafty religious loophole. “The water coming through each hole counts as a separate bath.”

[42]Or, as of 2007, an adult. Egyptian scholar Ezzat Attiya issued a fatwa, or religious opinion, extending breast‑milk‑son status to anyone a woman has “symbolically breastfed.” For convenience’s sake, drivers and deliverymen could, by drinking five glasses of a woman’s breast milk, be permitted to spend time alone with her. In the ensuing ruckus, another scholar insisted the man would have to drink directly from the woman’s breast. Which is crazier: that Saudi courts, in 2009, sentenced a woman to forty lashes and four months in prison for allowing a bread deliveryman inside her home, or the notion that she might have avoided punishment by letting him suckle from her breast? The woman was seventy‑five, if that helps you with your answer.

[43]But not its bubbles. Frothiness is a hallmark of proteins in general; saliva has more than a thousand kinds. Proteins bind to air. When you whip cream or beat eggs, you are exposing maximum numbers of proteins to air, which is then pulled into the liquid, forming bubbles. That disturbing white foam on the cheeks and necks of racehorses is saliva whisked by the bit. (The whisking of semen is complicated by its coagulating factor. Should you wish to know more, I direct you to the mucilaginous strands of the World Wide Web.)

[44]Literally. The coating is real silver. That’s why the label says “For Decorative Use Only.” Like everyone else, environmental lawyer Mark Pollock didn’t realize you weren’t supposed to eat them. In 2005, Pollock sued PastryWiz, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, Dean & DeLuca, and a half‑dozen other purveyors of silver dragees, as they are known in the business. Pollock succeeded in getting the product off store shelves in California. Fear not, holiday bakers, silver dragees are available in abundance from online sellers, along with gold dragees, mini dragees, multicolored pastel dragees. And dragee tweezers. (With cupped ends “to easily grab individual dragees.”)

[45]As does this: Claims made by makers of mouthwash to kill 99 percent of oral bacteria are misleading. Silletti says half the species can’t be cultured in a lab; they grow only in the mouth. Or on other bacteria. “When you ask the companies for claim support, they will show you the statistics for the kinds they can culture.” How many others there are, or what mouthwash does to them, is unknown.

[46]In 1973, inquisitive cold researchers from the University of Virginia School of Medicine investigated “the frequency of exposure of nasal… mucosa to contact with the finger under natural conditions”–plainly said, how frequently people pick their nose. Under the guise of jotting notes, an observer sat at the front of a hospital ampitheater during grand rounds. Over the course of seven 30‑ to 50‑minute observation periods, a group of 124 physicians and medical students picked their collective noses twenty‑nine times. Adult Sunday school students were observed to pick at a slightly lower rate, not because religious people have better manners than medical personnel, but, the researchers speculated, because their chairs were arranged in a circle. In a separate phase of the study, the researchers contaminated the picking finger of seven subjects with cold virus particles and then had them pick their nose. Two of seven came down with colds. In case you needed a reason to stop picking your nose.

[47]Fear the fight bite: it can cause septic arthritis. In one study, 18 of 100 cases ended in amputation of a finger. Hopefully the middle one. In the aggressive patient, a missing middle finger may be good preventive medicine.

[48]The zookeepers, however, got very, very quiet. “So maybe,” said Bronstein in an e‑mail, “the dragon spit some of its quietness spray on them.” I am almost 100 percent sure that that is not a reference to Sharon Stone.

[49]The term quack derives from quacksalber , German for “quicksilver” (mercury’s nickname). It took a while for medicine to see the light. As late as 1899, the Merck Manual suggests mercury as an antisyphilitic, to “produce salivation.” Syphilitics weren’t the only ones salivating over mercury. Merck was, at the time, reaping profits from eighteen different “medicinal” mercuries.

[50]Not to be confused with the Nutter D. Marvel Museum of horsedrawn carriages or the Butter Museum, a working farm that “showcases all things butter, from various styles of butter dishes to the history of butter through the ages,” perhaps turning away briefly during butter’s history‑making 1972 role in Last Tango in Paris .

[51]Fingerprints come in three types: loop (65 percent), whorl (30 percent), and arch (5 percent). Oral processing styles for semisolid foods come in four: simple (50 percent), taster (20 percent), manipulator (17 percent), and tonguer (13 percent). Thus the millions of variations that make you the unique and delightful custard‑eater and fingerprint‑leaver that you are.

[52]I nominate Rhode Island.

[53]Assuming equal terrain and baggage count, about as fast as a tortoise–.22 miles per hour.

[54]Its full medical name, and my pen name should I ever branch out and write romance novels, is palatine uvula.

[55]Technical term: toothpack.

[56]1896 was a banner year for human‑swallowing, or yellow journalism. Two weeks after the Bartley story broke, the Times ran a follow‑up item about a sailor buried at sea. An axe and a grindstone, among other things, were placed in the body bag to sink the parcel. The man’s son, frantic with grief, plunged overboard. The next day, the crew hauled aboard a huge shark with an odd sound issuing from within. Inside the stomach, they found both the father and the son alive, one turning the grindstone while the other sharpened the axe, “preparatory to cutting their way out.” The father, the story explains, “had only been in a trance.” As had, apparently, the Times editorial staff.

[57]I challenge you to find a more innocuous sentence containing the words sperm, suction, swallow, and any homophone of seaman . And then call me up on the homophone and read it to me.

[58]Vallisneri named the fluid aqua fortis –not to be confused with aquavit , a Scandinavian liquor with, sayeth the Internet, “a long and illustrious history as the first choice for… special occasions,” like holidays or the opening of an ostrich stomach.

[59]At some point during the experiment, or possibly the follow‑up, wherein a live eel was pushed into the stomach and left with “just its head outside,” or one of the dozens of other vivisections, Bernard’s wife walked in. Marie Françoise “Fanny” Bernard–whose dowry had funded the experiments–was aghast. In 1870 she left him and inflicted her own brand of cruelty. She founded an anti‑vivisection society. Go, Fanny.

[60]Meaning “by way of the anus.” “Per annum,” with two n ’s, means “yearly.” The correct answer to the question, “What is the birth rate per anum?” is zero (one hopes). The Internet provides many fine examples of the perils of confusing the two. The investment firm that offers “10% interest per anum” is likely to have about as many takers as the Nigerian screenwriter who describes himself as “capable of writing 6 movies per anum” or the Sri Lankan importer whose classified ad declares, “3600 metric tonnes of garlic wanted per anum.” The individual who poses the question “How many people die horse riding per anum?” on the Ask Jeeves website has set himself up for crude, derisive blowback in the Comments block.

[61]Those of you who swallow oysters without chewing them may be curious as to the fate of your appetizers. Mollusk scientist Steve Geiger surmised that a cleanly shucked oyster could likely survive a matter of minutes inside the stomach. Oysters can “switch over to anaerobic” and get by without oxygen, but the temperature in a stomach is far too warm. I asked Geiger, who works for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, about the oyster’s emotional state during its final moments inside a person. He replied that the oyster, from his understanding, is “pretty low on the scale.” While a scallop, by comparison, has eyes and a primitive neural network at its disposal, the adult oyster makes do with a few ganglia. And mercifully, it is likely to go into shock almost immediately because of the low pH of the stomach. Researchers who need to sedate crustaceans use seltzer water because of its low pH. Geiger imagined it would have a similar effect on bivalves. But you might like to chew them nonetheless, because they’re tastier that way.

[62]How remains a matter of debate. I had heard that pythons suffocate prey by tightening on its exhale and preventing further inhales. Secor says no; prey passes out too quickly for that to be the explanation. “You’d still have oxygen circulating in the blood, like you’re holding your breath.” He thinks it’s more likely that the constriction shuts off blood flow, more like strangulation than suffocation. An experiment was planned at UCLA but nixed by the animal care committee. Secor would volunteer himself. “I think we’d all like to have a giant snake constrict us in a controlled situation and see what happens–could we still inhale?” It’s possible he’s a little nuts. But in a good way.

[63]Excuse me, I mean the Dried Plum Capital of the World. The change was made official in 1988, as part of an effort to liberate the fruit from its reputation as a geriatric stool softener. Yuba City has Vancouver, Washington, to blame for that. The original Prune Capital of the World, Vancouver was the home of the Prunarians, a group of civic‑minded prune boosters who, back in the 1920s, touted the laxative effects of dried plums. The Prunarians also sponsored an annual prune festival and parade. A 1919 photo reveals a distinct lack of festiveness and pruniness. Eight men in beige uniforms stand in a row across the width of a rain‑soaked pavement. A ninth stands on his own just ahead of the row, similarly attired. Presumably he is their leader, though you expect a little foofaraw from an entity known as the Big Prune. Or the Big Dried Plum, as Yuba City would like you to call him.

[64]Though you do read case reports in which patients say they heard a bursting noise, the experience is more often described as a sensation, as in “a sensation of giving way.” The “sudden explosion” recalled by a seventy‑two‑year‑old woman following a meal of cold meat, tea, and eight cups of water was more likely something she felt, not heard. (The old eight‑cups‑of‑water‑a‑day advice should possibly be qualified with the clause, “but not all at once.”)

[65]With one exception. While the consumption record for many foods exceeds eight and even ten pounds, no one has ever been able to eat more than four pounds of fruit cake.

[66]Available in four languages, with minor modifications.The Portuguese edition, for instance, makes a distinction between the sausage of Types 2 and 3 (referred to as linguiça , a fatter German‑style product) and that of Type 4, which is compared to salsicha (the more traditional wiener). The Bristol scale is, after all, a communication aid for physicians and patients. The more specific phrasing was undertaken “for better comprehension across Brazil.”

[67]In a more perfect world, Whitehead would be a dermatologist, just as my gastroenterologist is Dr. Terdiman, and the author of the journal article “Gastrointestinal Gas” is J. Fardy, and the headquarters of the International Academy of Proctology was Flushing, New York.

[68]Back in 2007, while researching a different book, I came across a journal article with a lengthy list of foreign bodies removed from rectums by emergency room personnel over the years. Most were predictably shaped: bottles, salamis, a plantain, and so on. One “collection”–as multiple holdings were referred to–stood out as uniquely nonsensical: spectacles, magazine, and tobacco pouch. Now I understand! The man had been packing for solitary.

[69]Biofeedback can help. The anal sphincter can be briefly wired such that tightening and relaxing causes a circle on a computer screen to constrict and widen. The patient is instructed to bear down while keeping the circle wide. The maker of that program has one for children, called the Egg Drop Game, wherein clenching and relaxing causes a basket to move back and forth to catch a falling egg. The website of the American Egg Board has a version of the Egg Drop Game that does not require an anus (or cloaca) to play, just a cursor.

[70]Especially if the exam entails defecography, which is pretty much what it sounds like. The patient is the star in an X‑ray movie viewed by an audience of technicians, interns, and radiologist. “As close to pornography as medicine will come,” says gastroenterologist Mike Jones. Worse, the patient is passing a barium‑infused “synthetic stool” crafted from a paste of plasticine (or in simpler days, rolled oats) and introduced wrong‑way into the rectum. For the constipated patient, notes Jones, it can be a real ordeal. “It’s like, ‘Dude, if I could do this, I wouldn’t be here now.’”

[71]Customs officers at Frankfurt Airport have it easier. Suspects are brought to the glass toilet, a specially designed commode with a separate tank for viewing and hands‑free rinsing–kind of an amped‑up version of the inspecting shelf on some German toilets. P.S.: The common assumption that the “trophy shelf” reflects a uniquely German fascination with excrement is weakened by the fact that older Polish, Dutch, Austrian, and Czech toilets also feature this design. I prefer the explanation that these are the sausage nations, and that prewar pork products caused regular outbreaks of intestinal worms.

[72]Other red flags for customs agents include the unique breath odor created by gastric acid dissolving latex, and airline passengers who don’t eat. For years, Avianca cabin crew would take note of international passengers who refused meals, and report the names to customs personnel upon landing.

[73]Occasionally the justice system has no choice but to step right in it. In State of Iowa v. Steven Landis , an inmate was convicted of squirting a correctional officer with a feces‑filled toothpaste tube, a violation of Iowa Code section 708.3B, “inmate assault–bodily fluids or secretions.” Landis appealed, contending that without expert testimony or scientific analysis of the officer’s soiled shirt, the court had failed to prove that the substance was in fact feces. The state’s case had been based on eyewitness, or in this case nosewitness, testimony from other correctional officers. When asked how he knew it was feces, one officer had told the jury, “It was a brown substance with a very strong smell of feces.” The appeals judge felt this was sufficient.thanks to Judge Colleen Weiland, who drew my attention to the case and did me the favor of forwarding a logistical question to the presiding judge, Judge Mary Ann–may it please the author–Brown. “It appeared,” Brown replied, “that he liquefied the material and then dripped it or sucked it into the tube.”

[74]Seriously, published by Oxford University Press. But highly readable. So much so that the person who took Inner Hygien e out of the UC Berkeley library before me had read it on New Year’s Eve. I know this because she’d left behind her bookmark–a receipt from a Pinole, California, In‑N‑Out Burger dated December, 30, 2010–and because every so often as I read, I’d come upon bits of glitter. Had she brought the book along to a party, ducking into a side room to read about rectal dilators and slanted toilets as the party swirled around her? Or had she brought it to bed with her at 2 A.M., glitter falling from her hair as she read? If you know this girl, tell her I like her style.

[75]Of or relating to the belly or intestines. With crushing disappointment, I learned that Dr. Gregory Alvine is an orthopedist. Staff at the oxymoronic Alvine Foot & Ankle Center did not respond to a request for comment.

[76]You would think the percentage would be higher, but in fact 80 to 90 percent of nondigestible objects that make it down the esophagus pass the rest of their journey without incident. If a man can swallow and pass a partial denture, a drug mule has little to worry about.

[77]Close to but not quite the most egregious indignity bestowed on a corpse by drug dealers. Smugglers have occasionally recruited the mute services of a corpse being repatriated for burial and stuffed the entire length of the dead man’s GI tract. Heroin sausage.

[78]A term coined by sexologist Thomas Lowry. In his efforts to research fisting, Lowry found himself writing letters to strangers at academic institutions that would begin like this: “Dear Dr. Brender: We spoke on the phone several months ago about ‘fist‑fucking.’ At that time you mentioned two surgical articles.” There was no academic term, so eventually Lowry made one up. “I Googled it recently,” he told me, “and found over 2,000 hits. Made me chuckle.”

[79]Simon refined his technique on cadavers, rupturing a bowel or two along the way, and then began offering training seminars. Cadavers were replaced with live, chloroformed women, thighs flexed on their abdomens. “A large number of professors and physicians” flew all the way to Heidelberg to practice “the forcible entrance.”

[80]Flammable is a safety‑conscious version of inflammable . In the 1920s, the National Fire Protection Association urged the change out of concern that people were interpreting the prefix in to mean “not”–as it does in insane . Though surely those same people must have wondered why it was necessary to warn of the presence of gas that will not burst into flame .

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 3465;