THE AIR WAR BOGS DOWN

Once it became clear by the fourth day that the air offensive was not having its hoped‑for effect on Milosevic, Clark received authorization from the NAC to proceed to Phase II, which entailed ramped‑up attacks against a broader spectrum of fixed targets in Serbia and against dispersed and hidden VJ forces in Kosovo. Attacks during the preceding three nights had focused mainly on IADS targets. Phase II strikes shifted the emphasis from SEAD to interdiction, with predominant stress on cutting off VJ and MUP lines of communication and attacking their choke points, storage and marshaling areas, and any tank concentrations that could be found. Immediately before Phase II began, NATO ambassadors had argued for more than eight hours, well past midnight, over whether to expand the target list. General Naumann insisted at that session that it was time to start “attacking both ends of the snake by hitting the head and cutting off the tail.”[46]His use of that bellicose‑sounding metaphor reportedly infuriated the Greek and Italian representatives, who had been calling for an Easter bombing pause in the hope that it might lead to negotiations.[47]

NATO went into this second phase earlier than anticipated because of escalating Serb atrocities on the ground. Up to that point, the air attacks had had no sought‑after effect on Serb behavior whatsoever. On the contrary, Serbia’s offensive against the Kosovar Albanians intensified, with Serb troops burning villages, arresting dissidents, and executing supposed KLA supporters. The Serbs continued unopposed in their countercampaign of ethnic cleansing, ultimately forcing most of the 1.8 million ethnic Albanians in Kosovo from their homes.[48]

By the start of the second week, Clinton administration officials acknowledged that Operation Allied Force had failed to meet its declared goal of halting Serbian violence against the ethnic Albanians.[49]Echoing that judgment, Clark added that NATO was confronting “an intelligent and capable adversary who is attempting to offset all our strategies.”[50]It was becoming increasingly clear that at least one element of Milosevic’s strategy entailed playing for time. Yet although the humanitarian crime of ethnic cleansing gave the Serbs an immediate tactical advantage, it also came at the long‑term cost of virtually forcing NATO to stay the course. The bombing effort thus evolved into a race between those Serb forces trying to drive the ethnic Albanians out of Kosovo and NATO forces trying to hinder that effort–or, failing that, to punish Milosevic badly enough to make him quit.

Five B‑1Bs were added to the U.S. Air Force’s bomber contingent at the start of the second week. In preparing them for combat, what normally would have taken months of effort to program the aircraft’s mission computers was compressed into fewer than 100 hours during a single week as Air Force officers and contractors updated the computers with the latest intelligence on enemy radar and SAM threats. One aircraft with the latest updated software installed, the Block D upgrade of the Defensive System Upgrade Program, passed a critical flight test at the 53rd Wing at Eglin AFB, Florida, and two B‑1s were committed to action over Yugoslavia two days later. These aircraft, which, alongside the B‑52s, operated out of RAF Fairford in England, employed the Raytheon ALE‑50 towed decoy to good effect for the first time in combat.[51]They were still test‑configured aircraft flown by test crews. The B‑1s, all test‑configured with Block D upgrades, typically flew two‑ship missions against military area targets, such as barracks and marshaling yards.

While the Serb pillaging of Kosovo was unfolding on the ground, NATO air attacks continued to be hampered by bad weather, enemy dispersal tactics, and air defenses that were proving to be far more robust than expected. In the absence of a credible NATO ground threat, which the United States and NATO had ruled out from the start, VJ forces were able to survive the air attacks simply by spreading out and concealing their tanks and other vehicles. More than half of the nightly strike sorties returned without any weapons expended owing to adverse weather in the target area. Only four days out of the first nine featured weather offering visibility conditions suitable for employing laser‑guided bombs (LGBs). By the end of Day 9, only 15 percent of the 2,700 sorties flown had actually been bombing missions. In all, it took NATO 12 days to complete the same number of strike sorties that had been conducted during the first 12 hours of Desert Storm.

To all intents and purposes, the difference between Phase II and Phase I was indistinguishable as far as the intensity of NATO’s air attacks was concerned. The commencement of Phase II was characterized as more of an evolution than a sharp change of direction. On that point, NATO’s spokesman at the time, RAF Air Commodore David Wilby, said that the operation was “just beginning to transition” from IADS targets to fielded VJ and MUP forces.[52]By the start of the second week, merely 1,700 sorties had been flown, only 425 of which consisted of strike sorties against a scant 100 approved targets.[53]Up to that point, air operations had averaged only 50 strike sorties a night, in sharp contrast to Desert Storm, in which the daily attack sortie rate was closer to 1000. The operational goal of Allied Force was still officially described as merely seeking to “degrade” Serbia’s military capability. In one of the first hints of growing concern that the air effort was not going well, a senior U.S. general spoke of at least “several weeks” of needed attacks to beat down VJ and MUP forces to the breaking point.[54]Similarly, by the start of the second week, an administration official declared that the goal of the bombing was to “break the will” of the Belgrade leadership, implying an open‑ended air employment strategy.[55]Earlier, administration spokesmen had indicated that they believed that just a few days of bombing would do the trick.

NATO soon discovered that it was dealing with a cunning opponent who was quite accomplished at hiding. As a result, it conceded that it was being forced to “starve rather than shoot them out.”[56]Even with clear skies at the beginning of the third week, NATO pilots were having little success at interdicting those VJ and MUP troops and paramilitary thugs in Kosovo who were carrying out the executions, village burnings, and forced emigration of Kosovar Albanians, to say nothing of finding and attacking their tanks and artillery. Since attacking dispersed VJ troops directly was proving to be too difficult, attacks against fielded forces concentrated instead on second‑order effects by going after bases, supplies, and petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL).

On Day 6, Clark sought NATO approval to increase the pressure on Milosevic by attacking the defense and interior ministry headquarters in Belgrade. That request was disapproved by NATO’s political leaders, on the declared ground that such strikes were still “premature.”[57]The list of approved targets increased by about 20 percent at the end of the first week. Yet Clark still did not receive the full authority from NATO that he had sought. NATO Secretary General Javier Solana, in particular, expressed misgivings about a larger target set, saying that he was not persuaded that the time had come yet to intensify the operation so dramatically. As a result, Clark was forced to improvise changes to an original plan that had called for slow‑motion escalation, punctuated by pauses, disturbingly comparable to the flawed strategy employed during Operation Rolling Thunder over North Vietnam a generation earlier.

Phase III, which entailed escalated attacks against military leadership, command and control centers, weapons depots, fuel supplies, and other targets in and around Belgrade, commenced de facto on Day 9 with strikes against infrastructure targets in Serbia. These included the Petrovaradin bridge on the Danube at Novi Sad; a bridge on the Magura‑Belacevac railway; the main water supply to Novi Sad; and targets near Pec, Zatric, Decane, Dragodan, Vranjevac, Bajin Basta, and the Pristina airport.[58]No targets in or near Belgrade, however, were attacked. At this point, Allied Force was still generating no more than 50 ground‑attack sorties a day.[59]There was mounting unease over the fact that attacks against empty barracks and other military facilities were having no effect on Serb behavior now that VJ and MUP forces were well dispersed. It soon became evident that Milosevic had hunkered down in a calculated state of siege. Evidently sensing that he had accomplished many of his goals on the ground and believing that he could now succeed in dividing NATO, he declared a unilateral cease‑fire on April 6. The United States and NATO, however, rejected that transparent ploy and pressed ahead with their attacks.

U.S. naval aviation, unavailable for the initial phase of Operation Allied Force, joined the fray when the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt arrived on station in the Ionian Sea south of Italy two weeks afterward, on April 6. The air wing assigned to the Theodore Roosevelt flew complete and self‑sustaining strike packages, including F‑14Ds and F/A‑18s for surface‑attack operations, EA‑6Bs for the suppression of enemy air defenses, F‑14s in the role of airborne forward air controllers, and E‑2Cs performing as ABCCC platforms. These packages typically flew missions only against dispersed and hidden enemy forces in Kosovo, although on one occasion, on April 15, they struck a hardened aircraft bunker at the Serbian air base at Podgorica in Montenegro in the first of several allied efforts to neutralize a suspected air threat against the U.S. Army’s Task Force Hawk deployed in Albania (see below).[60]The E‑2C, normally operated as an airborne early warning (AEW) platform to screen the carrier battle group from enemy air threats, was used in Allied Force to provide an interface between the CAOC and naval air assets operating in the theater, including both strikers and intelligence collectors.[61]

It was hard during the first few weeks for outside observers to assess and validate the Pentagon’s and NATO’s claims of making progress because U.S. and NATO officials had so deliberately refrained from disclosing any significant details about the operation. Instead, administration and NATO sources limited themselves to vague generalizations about the air war’s effects, using such hedged terms as “degrading,” “disrupting,” and “debilitating” rather than the more unambiguous “destroying.” On this studiously close‑mouthed policy, the Defense Department’s spokesman, Kenneth Bacon, declared that a precedent was being intentionally set, since both Secretary Cohen and General Shelton had seen a need to “change the culture of the Pentagon and make people more alert to the dangers that can flow from being too generous–or you could say profligate or lax–with operational details.”[62]

In one of the first tentative strikes against enemy infrastructure, the main telecommunications building in Pristina, the capital city of Kosovo, was taken out by two GBU‑20 LGBs dropped by an F‑15E on April 6. Yet the air effort as a whole remained but a faint shadow of Operation Desert Storm, with only 28 targets throughout all of Yugoslavia attacked out of 439 sorties in a 24‑hour period during the operation’s third week.[63]As for the hoped‑for “strategic” portion of the air war against the Serb heartland, Clark was still being refused permission by NATO’s political leaders to attack the state‑controlled television network throughout Yugoslavia. On April 12, attacks were conducted against an oil refinery at Pancevo and other infrastructure targets, with the Pentagon announcing that all of Yugoslavia’s oil refineries had been destroyed but that some stored fuel remained available. Also on April 12, the 20th day of the air attacks, NATO missions into the newly designated Kosovo Engagement Zone (KEZ) commenced with attempted attacks against VJ and MUP tanks, artillery, wheeled vehicles, and other assets fielded in Kosovo, in response to Belgrade’s escalated ethnic cleansing of the embattled province.

By the third week, NATO’s strategic goals had shifted from seeking to erode Milosevic’s ability to force an exodus of Kosovar Albanian civilians to enforcing a withdrawal of Serb forces from Kosovo and a return of the refugees home. That shift in strategy was forced by Milosevic’s early seizure of the initiative and his achievement of a near–fait accompli on the ethnic cleansing front. Up to that point, President Clinton had merely insisted that the operation’s goal was to ensure that Milosevic’s military capability would be “seriously diminished.”[64]

As Operation Allied Force continued to bog down entering its third week, the influential London Economist pointedly observed that it was not “just NATO whose credibility is at risk. At home, the Defense Department’s post‑Gulf‑war prestige is also in the balance, along with the doctrines of high‑tech dominance that the Gulf war encouraged people to believe. America’s faith in air power, formed by the precision bombing of Iraqi targets, has already been tested by Mr. Hussein’s durability. If the current bombing fails to unseat Mr. Milosevic, the air power doctrine could collapse.”[65]Numerous factors accounted for why the operation’s early performance had proven so disappointing. They included adverse weather, difficult terrain, a wily and determined opponent, poor strategy choices by the Clinton administration and NATO’s political leaders, and, perhaps most of all, the burdens of having to coordinate an air operation with 18 often highly independent‑minded allies.

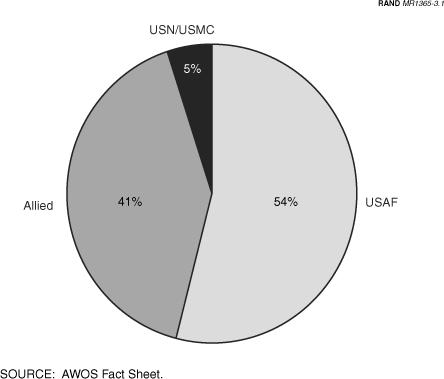

By the end of the third week, in large measure out of frustration over the operation’s continued inability to get at the dug‑in and elusive VJ positions in Kosovo, Clark requested a deployment of 300 more aircraft to support the effort. That request, which would increase the total number of committed U.S. and allied aircraft to nearly 1,000, entailed more than twice the number of allied aircraft (430) on hand when the operation began on March 24–and almost half of what the allied coalition had had available for Desert Storm. For the United States, it represented a 60 percent increase over the 500 U.S. aircraft already deployed (see Figure 3.1 for the ultimate proportions of U.S. and allied aircraft provided to support Allied Force). Among other things, it prompted understandable concern about where to base them, with NATO looking to France, Germany, Hungary, Turkey, and the Czech Republic for possible options.[66]

Figure 3.1–U.S. and Allied Aircraft Contributions

The call for 300 additional aircraft followed on the heels of an earlier request by Clark for 82 more aircraft, which had been promptly approved by the Pentagon. This time, Pentagon officials expressed surprise at the size of Clark’s request and openly questioned whether it would be approved in its entirety.[67]The principal concern was that it would draw precious assets, notably such low‑density/high‑demand aircraft as the E‑3 airborne warning and control system (AWACS) and EA‑6B Prowler, away from Iraq and Korea. The service chiefs reportedly complained that Clark’s requested quantities represented a clear case of overkill and that USEUCOM was not making the most of the forces already at its disposal.

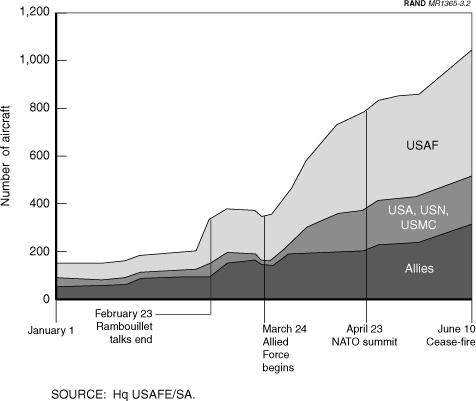

In addition, Clark asked for the USS Enterprise and its 70‑aircraft air wing, which would necessitate extending the carrier’s cruise length and thereby breaking a firm Navy rule of not keeping aircrews and sailors at sea for any longer than six months at a single stretch. The request was opposed by the chief of naval operations, Admiral Jay Johnson, and Secretary of the Navy Richard Danzig. In the end, the Enterprise was made available by the Navy for diversion to the Adriatic as requested, but its air wing was never tasked by the CAOC, and it never participated in Allied Force. Once the additional aircraft were approved, NATO asked Hungary to make bases available and Turkey to help absorb those aircraft. Figure 3.2 shows how the intheater buildup of aircraft ultimately played itself out.

As a part of his requested force increment, Clark also asked for a deployment of Army AH‑64 Apache attack helicopters. Although the other aircraft were eventually approved by Secretary Cohen and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), this particular request was initially disapproved, on the avowed premise that since attack helicopters are typically associated with land combat, the introduction of Apaches might be misperceived by some allies as a precursor to a ground operation. A more serious concern almost surely was that the Apaches might not survive were they to be committed to combat in the still‑lethal Serb SAM and AAA environment.

Figure 3.2–In‑Theater Aircraft Buildup

In the end, despite Army and JCS reluctance, Clark prevailed in his request for the Apaches and announced that 24 would be deployed to Albania from their home base at Illesheim, Germany. Pentagon spokesmen went out of their way to stress that the Apaches were intended solely as an extension of the air effort and not as an implied prelude to future ground operations.[68]To support the major aircraft buildup requested by Clark, the Pentagon asked President Clinton to authorize a call‑up of 33,000 U.S. reservists and National Guard members–in the largest single reserve‑force activation since Desert Shield in 1990–1991, when 265,000 Guard and reserve personnel had been mobilized for possible combat or combat‑support duty in the Gulf. As the bombing entered its 27th day, Clinton asked Congress for $5.458 billion in emergency funding to continue financing the air effort, with $3.6 billion to cover air operations from March 24 to the end of FY99, $698 million for additional cruise missiles and precision‑guided munitions (PGMs), and $335 million for refugee relief.

Meanwhile, Operation Allied Force remained as stalled as ever, with no sign of tangible progress. Clark had wanted to go after command bunkers and other vital targets in Serbia from the very start of the operation, but it took more than a month for NATO’s political leaders to approve an attack on Milosevic’s villa at Dobanovci. The Dutch government steadfastly refused to grant approval to bomb his presidential palace because the latter was known to contain a painting by Rembrandt.[69]NATO’s ambassadors would not even approve strikes against occupied VJ barracks out of expressed concern over causing too many casualties among helpless enemy conscripts.[70]

By the end of the first month, as many as 80 percent of the strikes conducted had been revisits to fixed targets that had been attacked at least once previously. This was due in part to rapid enemy regeneration and reconstitution efforts, but mainly to the limited number of targets that had been approved by NATO’s civilian leaders, the often maddeningly slow target generation and approval process, and

SACEUR’s desire to keep the bombs falling on Serbia notwithstanding those constraints. The Serbs repeatedly demonstrated an ability to perform workarounds and rebuild their damaged communications facilities, with some IADS installations being brought back on line less than 24 hours of having been attacked.[71]Furthermore, among all the Air Tasking Order (ATO) releases of combat aircraft against preassigned targets, some failed to get airborne because of weather cancellations or maintenance‑related aborts, and others either returned home without having expended their ordnance because of rules‑of‑engagement constraints or having failed to hit their assigned aim points when they did succeed in dropping munitions. These considerations also figured prominently in the low effectiveness of the overall effort.

As the air war entered its fifth week, Clark admitted that Milosevic was still pouring reinforcements into Kosovo continuously and that “if you actually added up what’s there on a given day, you might find that he’s strengthened his forces in there.”[72]Much as during some periods of Desert Storm, adverse weather at the five‑week point had forced a cancellation or failure of more than half of all scheduled bombing sorties on 20 of the first 35 days of air attacks. Seemingly resigned to a waiting game as the air war appeared stalled after more than a month of continual bombing, a senior NATO diplomat confessed that it now felt as though Operation Allied Force “had been put on autopilot. Now we are basically waiting for something to crack in Belgrade.”[73]In light of the stalled offensive, some saw the air war now threatening to stretch into summer 1999, if not longer.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 993;