COUNTDOWN TO CAPITULATION

Following an inadvertent attack on a refugee convoy near Djakovica, Kosovo, on April 14–occasioned in part by a suspected visual misidentification by the participating USAF F‑16 pilots (see Chapter Six)–the altitude floor of 15,000 ft that had been imposed at the start of the air war was eased somewhat in the southern portion, and NATO forward air controllers (FACs) flying over Kosovo were cleared to descend to as low as 5,000 ft if necessary, to ensure positive identification of ground targets in the KEZ.[109]Direct attacks on suspected VJ positions in Kosovo by B‑52s occurred for the first time on May 5 and again the following day. Clark declared afterward that 10 enemy armor concentrations had been hit and that the Serbs were no longer able to continue their ethnic cleansing. NATO spokesmen further reported that enemy troops in the field were running low on fuel and that VJ and MUP morale had declined.[110]A day later, NATO claimed that it had destroyed 20 percent of the VJ’s artillery and armor deployed in Kosovo. As for infrastructure attacks, only two of the 31 bridges across the Danube in Yugoslavia were said to be still functional by the end of the week. During the second week of May, however, enemy attack helicopters conducted an attack against the village of Kosari along the main supply route for the KLA. They also served as spotters for VJ artillery against KLA pockets of resistance.[111]Those operations indicated that NATO had done an imperfect job of preventing any and all enemy combat aircraft from flying.

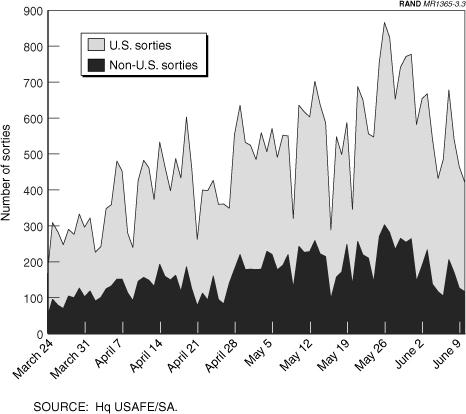

On May 12, roughly 600 Allied Force sorties were launched all told, including the highest daily number of shooter sorties to date. (See Figure 3.3 for the overall trend line in U.S. and allied sorties flown over the 78‑day course of Allied Force. Most of the troughs in that trend line indicate sortie drawdowns or cancellations occasioned by nonpermissive weather over Serbia.) The multiple waves of successive large force packages commenced with a sunrise launch of 36 aircraft, including USAF F‑16s and A‑10s, RAF Harrier GR. Mk 7s, French Jaguars and Super Etendards, Italian AMXs, and Canadian CF‑18s. A subsequent late‑morning launch featured 32 aircraft, consisting of RAF Tornado GR. Mk 1s, French Jaguars, and USAF

Figure 3.3–U.S. and Allied Sorties Flown

F‑16s, followed by 30 F‑15Es and 16 more later in the surge. A mid‑afternoon strike with 28 jets was then followed by 24 more, with the day finally ending with a midnight package of 38 strikers, including B‑1Bs and B‑52s.[112]

Three days later, General Jumper declared that NATO had achieved de facto air superiority over Yugoslavia, enabling attacking aircraft to “go anywhere we want in the country, any time,” even though the skies were admittedly “still dangerous.”[113]Not long thereafter, an option became available to attack from the north with 24 F/A‑18Ds of Marine Air Group 31 deployed to Taszar, Hungary. That option promised to further isolate Yugoslavia, make it appear surrounded, and force its remaining air defenses to work harder by having to look in more than one direction rather than mainly toward a single attack axis from the west. It also promised to avoid adding to the already severe air traffic congestion over the Adriatic and in other western approaches to Yugoslavia.

As allied air operations against VJ troops in the KEZ became more aggressive, a clear preference for the USAF’s A‑10 over the Army’s AH‑64 Apaches in Albania became evident because weather conditions over Kosovo had improved by that time, rendering the Apache’s under‑the‑weather capability no longer pertinent and because enough of the Serb IADS had been deemed weakened or intimidated to make it safer to operate the A‑10s at lower altitudes. Moreover, the Apaches were deemed to be more susceptible to AAA and infrared SAM threats than were the faster and higher‑flying A‑10s. President Clinton himself later reinforced those reservations when he commented in mid‑May that the risk to the Apache pilots remained too great and that because of recent weather improvements, “most of what the Apaches could do [could now] be done by the A‑10s at less risk.”[114]

Later on in May, allied fighters and USAF heavy bombers committed against suspected enemy troop positions in the KEZ were joined for the first time by USAF AC‑130 gunships, which offered an additional standoff capability against enemy vehicles and other ground targets with their accurate 40mm Bofors gun, 25mm Gatling gun, and 105mm howitzer. The AC‑130, however, was only used over areas where there was no known or suspected presence of operational SAM batteries and always flew above the reach of IR SAMs and AAA. When targets of opportunity presented themselves on rare occasions, sensor platforms that detected ground vehicular movement would pass the coordinates and target characterization information to the EC‑130 ABCCC, which, in turn, would vector NATO attack aircraft into the appropriate kill box, first to confirm that the targets were valid and then to engage them. The ABCCC also controlled the ingress and egress of attacking fighters and maintained battlespace deconfliction throughout ongoing operations.

Once Serbia’s air defenses became a less imminent threat, the air war also saw a heightened use of B‑52s, B‑1s, and other aircraft carrying unguided bombs.[115]By the end of May, some 4,000 free‑fall bombs, around 30 percent of the total number of munitions expended altogether, had been dropped on known or suspected VJ targets in the KEZ. There was a momentary resurgence of Serb SAM activity later that month, with more than 30 SAMs reportedly fired on May 27, the greatest number launched any night in nearly a month.[116]That heightened activity was assessed as reflecting a determined last‑ditch Serb effort to down at least one more NATO aircraft. (An F‑117 had been shot down during the air war’s fourth night, and a USAF F‑16 had later been downed on the night of May 2.)[117]

In what was initially thought to have been a pivotal turn of events in the air effort against enemy ground forces, the newly enlarged and hastily trained KLA, estimated to have been equipped with up to 30,000 automatic weapons, including heavy machine guns, sniper rifles, rocket‑propelled grenades, and antitank weapons, launched a counteroffensive on May 26 against VJ troops in Kosovo. That thrust, called Operation Arrow, involved more than 4,000 guerrillas of the 137th and 138th Brigades and drew artillery support from the Albanian army, with the aim of driving into Kosovo from two points along the province’s southwestern border, seizing control of the highway connecting Prizren and Pec, and securing a safe route for the KLA to resupply its beleaguered fighters inside Kosovo.

Operation Arrow represented the first major assault by KLA rebels in more than a year. It was evidently intended to demonstrate both to Milosevic and to NATO that the KLA remained a credible fighting presence in Kosovo. The assault was thwarted at first by VJ artillery and infantry counterattacks, which indicated that the VJ still had plenty of fight in it despite 70 days of intermittent NATO bombing. Three days after launching their assault, the rebels found themselves badly on the defensive, with some 250 KLA fighters pinned down by 700 VJ troops near Mount Pastrik, a 6,523‑ft peak just inside the Kosovo‑Albanian border.

For abundant good reasons, not least of which was a determination to avoid even a hint of appearing to legitimize the KLA’s independent actions, NATO had no interest in serving as the KLA’s de facto air force and repeatedly refused to provide it with the equipment it would have needed for its troops to have performed directly as ground forward air controllers (FACs). The KLA did, however, receive allied support in other ways. There had been earlier unconfirmed reports going as far back as the air war’s second week that KLA guerrillas had been covertly assisting NATO in the latter’s effort to find and target VJ forces in Kosovo.[118]The first known direct NATO air support to the KLA occurred on the day that Operation Arrow commenced. It was confirmed both by KLA fighters in Albania and by military officials in Washington.

Although the Clinton administration denied helping the KLA directly, U.S. officials did admit that NATO had responded to “urgent” KLA requests for air support to turn back the VJ counterattack against its embattled troops near Mount Pastrik. In addition to the support they attempted to provide at Mount Pastrik, NATO aircraft attacked VJ targets near the Kosovar villages of Bucane and Ljumbarda, enabling the rebels to capture those villages. The KLA kept NATO informed of its positions in part so that its troops would not be inadvertently bombed, which had occurred two weeks earlier in an accidental NATO attack on a KLA barracks in Kosari.[119]KLA guerrillas used cell phones to convey target coordinates to their base commanders, who, in turn, relayed that information to NATO military authorities.

Throughout most of Allied Force, NATO and the KLA fought parallel but separate wars against VJ and MUP forces in Kosovo, and both the U.S. government and the KLA denied coordinating their operations in advance. NATO did acknowledge, however, that rebel attacks on the ground had helped flush out VJ troops and armor and to expose them to allied air strikes on at least a few occasions, and that Clark had authorized the communication of KLA target location information to attacking NATO aircrews indirectly through the ABCCC. The KLA further acknowledged that NATO air strikes had helped its ground operations.[120]Despite NATO denials throughout the air war that it was aiding the KLA, it became evident that cooperation between the two was considerably greater than had been previously admitted. As reported by KLA soldiers, the KLA had begun as early as May 10 to supply NATO with target intelligence and other battlefield information at NATO’s request, with the KLA’s chief of staff, Agim Ceku, working with NATO officers in northern Albania. While refusing to elaborate on specifics, KLA spokesmen admitted that Ceku had been the KLA’s principal point of contact with NATO. It was also Ceku who had participated in Croatia’s 1995 Operation Storm offensive that drove out the Krajina Serbs and helped end the fighting in Bosnia.[121]

Ultimately, VJ forces managed to repulse the KLA assault at Mount Pastrik. To do so, however, they had to come out of hiding and move in organized groups, making themselves potential targets, especially for A‑10s, on those infrequent occasions when they were detected and approved for attack by the ABCCC or the CAOC.[122]When KLA actions forced VJ troops to concentrate enough tanks and artillery to defend themselves, NATO aircraft were occasionally able to detect and engage them. Enemy ground movements during the final two weeks were often first noted by the E‑8 joint surveillance target attack radar system (Joint STARS) or other sensors, even though the VJ studiously sought to maneuver in small enough numbers to avoid being detected. The sensor operators would then transmit the coordinates of suspected enemy troop concentrations to airborne forward air controllers who, in turn, directed both unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and fighters in for closer looks, and ultimately for attacks.[123]KLA ground movements were also displayed aboard the ABCCC, which was coordinating and controlling NATO attacks against VJ armored vehicles in Kosovo, deconflicting the attacking aircraft, and ensuring that KLA forces in close contact with the VJ were not inadvertently hit. Those operations represented classic instances of close air support, with KLA and enemy forces in close contact on the ground. The ABCCC and attacking NATO aircrews received commands directly from the allied CAOC in Vicenza, Italy, which, in at least one case, aborted an attack out of concern for hitting KLA fighters.[124]

Despite this heightened activity in the KEZ during the air war’s final days, however, the attacks did better at keeping VJ and MUP troops dispersed and hidden than they did at actually engaging and killing them in any significant numbers. Most attack sorties tasked to the KEZ did not release their weapons against valid military targets, but rather against so‑called dump sites for jettisoning previously unexpended munitions, sites that were conveniently billed by NATO target planners as “assembly areas.” Even the B‑52s and B‑1s, for all the free‑fall Mk 82 bombs they dropped during the final days, were tasked with delivering a high volume of munitions without causing any collateral damage. After the air war ended, it was never established that any of the bombs delivered by the B‑52s and B‑1s had achieved any militarily significant destructive effects, or that NATO’s cooperation with the KLA had yielded any results of real operational value. The steadily escalating attacks against infrastructure targets in and around Belgrade that were taking place at the same time, however, were beginning to produce a very different effect on Serb behavior.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 931;