THE ENDGAME

On June 2, with Operation Allied Force working at peak intensity and with weather and visibility for NATO aircrews steadily improving, Russia’s envoy to the Balkans, former Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, and Finland’s President Martti Ahtisaari, the European Union representative, flew to Belgrade to offer Milosevic a plan to bring the conflict to a close. Ahtisaari’s inclusion in the process was said by one informed observer to have grown out of a suggestion by Chernomyrdin that value might be gained from including a respected non‑NATO player on his mission.[125]The same day, after the two emissaries had essentially served him with an ultimatum that had been worked out and agreed to previously by the United States, Russia, the European Union, and Ahtisaari, Milosevic accepted an international peace proposal. Under the terms of the proposed agreement, he would accede to NATO’s demands for a withdrawal of all VJ, MUP, and Serb paramilitary forces from Kosovo; a NATO‑led security force in Kosovo; an unmolested return of the refugees to their homes; and the creation of a self‑rule regime for the ethnic Albanian majority that acknowledged Yugoslavia’s continued sovereignty over Kosovo. NATO would continue bombing pending the implementation of a military‑to‑military understanding that had been worked out between NATO and Yugoslavia on the conditions of Yugoslavia’s force withdrawal. The agreement, which came on the 72nd day of the air effort, was ratified the day after, on June 3, by the Serb parliament and was rationalized by Milosevic’s Socialist Party of Serbia on the ground that it meant “peace and a halt to the evil bombing of our nation.”[126]

Milosevic later met with loyalist and opposition leaders to explain the reasons for his decision to accept the peace plan. That was as strong an indicator as any to date that the United States and NATO were at the brink of success in their effort to get Yugoslavia’s 40,000 troops removed from Kosovo, the Kosovar refugees returned to their homes, and NATO‑dominated peacekeepers on Kosovo’s soil to ensure that the agreement was honored by Milosevic. The agreement stipulated that once all occupying VJ and MUP personnel had departed Kosovo, an agreed‑upon contingent of Serbs–numbering only in the hundreds, not thousands–could return to Kosovo to provide liaison to the various peacekeeping entities commanded by British Army Lieutenant General Sir Michael Jackson, help clear the minefields that they had earlier laid, and protect Serb interests at religious sites and border crossings.

The two‑page draft agreement further called for removing all Serb air defense equipment and weapons deployed within 15 miles of the Kosovo border by the first 48 hours so that NATO aircraft could verify the troop withdrawals unmolested by any threats. The plan envisaged a U.S. sector to be controlled, first, by 1,900 Marines with light vehicles and helicopters standing by aboard three ships in the Aegean and, later, by the full American force complement made up largely of Army tank and infantry units to be brought in from Germany. U.S. forces, including the Marines from the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit at sea and three Army battalions from the 1st Infantry Division in Germany, would make up 15 percent of the overall Kosovo Force (KFOR). The agreement similarly provided for British, French, Italian, and German sectors.

NATO refused to commit itself to an early halt to its air attacks, since its leaders knew that it would be extremely difficult to resume the bombing once the refugees began coming home. During the negotiations over the terms of Serb withdrawal, however, NATO pilots were under orders not to attack any enemy positions unless in direct response to hostile acts. After the Serb parliament agreed to the cease‑fire, no bombs fell on Belgrade for three consecutive nights. B‑52 strikes against dispersed VJ forces, however, continued.

No sooner had this accord been reached in principle than NATO and Serb military officials failed to reach an understanding on the conditions for VJ and MUP withdrawal. The talks quickly degenerated into haggling over when NATO would halt its air attacks and whether Serbia would have more than a week to get its troops out of Kosovo. The proximate cause of the breakdown in talks was a Serb demand that the UN Security Council approve an international peacekeeping force before NATO troops entered Kosovo. That heel‑dragging suggested that the Serbs were seeking to soften some of the terms of the settlement or, perhaps, were looking for more time to continue their fight with the KLA. Secretary Cohen and General Shelton allowed that extending the Yugoslav withdrawal by several days would be acceptable but that they would not countenance any deliberate attempts at delay. More specifically, the implementation of the Serb withdrawal was hung up on differences over the sequencing of four events: the start of the enemy pullout, a pause in NATO bombing, the passage of a UN resolution, and the entry of international peacekeepers with a “substantial NATO content.” In response to this willful foot‑dragging, NATO’s attacks, which initially had been scaled back after Milosevic accepted the proposed peace plan, resumed their previous level of intensity.

On June 7, at the same time as the talks were under way, VJ forces launched a renewed counterattack against the KLA in an area south of Mount Pastrik, where the two sides had been locked in an artillery duel since May 26. For a time, a major breakthrough in NATO’s air effort was thought to have occurred when the defending KLA forces flushed out VJ troops who had been dispersed around Mount Pastrik, creating what NATO characterized as a casebook target‑rich environment. Thanks to improved weather, a noticeable degradation of Serb air defenses, and the effective role thought to have been played by the KLA in forcing VJ troops to come out of hiding, two B‑52s and two B‑1Bs dropped a total of 86 Mk 82s on an open field in a daytime raid near the Kosovo‑Albanian border where VJ forces were believed to have been massed.[127]The initially estimated number of enemy troops caught in the open by the attack was 800 to 1,200, with early assessments suggesting that fewer than half had survived the attack.[128]It later appeared, however, that the number of enemy casualties was considerably less than originally believed–if, indeed, the attacking bombers had killed a significant number of VJ troops at all.

Whatever the case, the following day the United States, Russia, and six other member‑states agreed on a draft UN Security Council resolution to end the conflict. The resolution called for a complete withdrawal of Serb troops, police, and paramilitary forces from Kosovo and for all countries to cooperate with the war crimes tribunal that had indicted Milosevic.[129]The sequence finally agreed to was that the Serb force withdrawal would commence, NATO would concurrently halt its bombing, and only after those two actions occurred would the Security Council vote on the text of the agreement. The last provision was a token concession to Russia and China, whose representatives had insisted that the bombing be stopped before any Security Council vote was taken.

In the end, the VJ acceded to a six‑page agreement that permitted a KFOR presence of 50,000 peacekeepers commanded by a NATO general and having sweeping occupation powers over Kosovo. By the terms of the agreement, Serb forces would withdraw along four designated routes over 11 days, under the constant threat of resumed bombing in case of any willful delays.[130](Belgrade had asked for 17 days.) Kosovo was to be ringed by a 5‑km buffer zone, and NATO was to provide for the safe return of all refugees. After 78 days of continual bombing by NATO, the agreement was finally signed on June 9 in a portable hangar at a NATO airfield in Kumanovo, Macedonia, five miles south of the Yugoslav border. The 11 days granted to Yugoslavia for the troop withdrawal was another diplomatic concession, considering that NATO had initially insisted that the withdrawal be completed in 7 days.

NATO finally stopped the bombing upon verifying that the Serb withdrawal had begun, after which the UN Security Council approved, by a 14‑0 vote with China abstaining, a resolution putting Kosovo under international civilian control and the peacekeeping force under UN authority. With that, President Clinton declared that NATO had “achieved a victory.”[131]

Once NATO peacekeeping forces moved in on the ground in Kosovo, they began discovering the full extent of Serb atrocities committed against the Kosovar Albanians. Among other things, they found an interrogation center in Pristina that had been used by Serb police, in which thousands of Kosovar suspects were said to have been “processed.” Inside the bowels of the building, they came across garrotes with wooden handles, brass knuckles, broken baseball bats, chainsaws, and leather manacles and straps. They also were told by surviving Kosovars that the Serb police had spent three days burning records before the British paratroopers finally arrived.[132]Later, the British government estimated that some 10,000 ethnic Albanians had died at the hands of marauding Serbs during the course of Operation Allied Force.[133]

As the last of some 40,000 VJ and MUP personnel exited Kosovo on June 20 a few hours ahead of NATO’s deadline, NATO declared a formal end to the air war. The bombing had earlier been suspended informally for 10 days when the first Serb troops began leaving Kosovo. The departure of the last Serb forces and the arrival of the KFOR peacekeepers effectively brought an end to Yugoslav control over a province that had been a special and even sacred preserve of Serbia for centuries.

Initial estimates just before the cease‑fire went into effect claimed that the air war had taken out 9 percent of Serbia’s soldiers (10,000 of 114,000), 42 percent of its aircraft (more than 100 of 240), 25 percent of its armored fighting vehicles (203 of 825), 22 percent of its artillery pieces (314 of 1,400), and 9 percent of its tanks (120 of 1,270).[134]After the cease‑fire, the Pentagon claimed that the operation had destroyed 450 enemy artillery pieces, 220 armored personnel carriers, 120 tanks, more than half of Yugoslavia’s military industry, and 35 percent of its electrical power‑generating capacity.[135]General Shelton reported that 60 percent of the infrastructure of the Yugoslav 3rd Army, the main occupying force in Kosovo, had been destroyed, along with 35 percent of the 1st Army’s infrastructure and 20 percent of the 2nd Army’s.[136]The U.S. Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for air and space operations, Lieutenant General Marvin Esmond, announced that the allied bombing effort had destroyed a presumed 80 percent of Yugoslavia’s fixed‑wing air force, zeroed out its oil refining capability, and eliminated 40 percent of its army’s fuel inventory and 40 percent of its ability to produce ammunition. Many of these initial assessments were later discovered to have been overdrawn by a considerable margin.

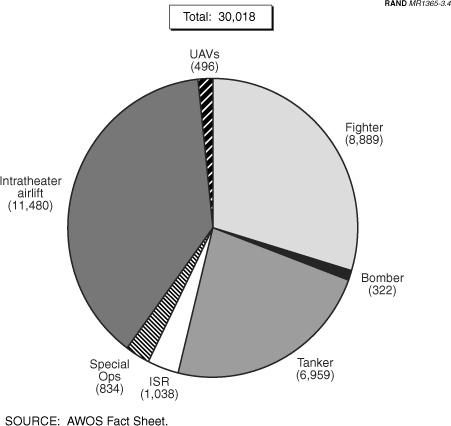

In the final tally, allied aircrews flew 38,004 out of a planned 45,935 sorties in all, of which 10,484 out of a planned 14,112 were strike sorties.[137]A later report to Congress by Secretary Cohen and General Shelton claimed that more than 23,300 combat missions, including defensive counterair patrols and defense suppression attacks, were flown altogether, entailing weapon releases against roughly 7,600 desired mean points of impact (DMPIs) on fixed targets and slightly more than 3,400 presumed mobile targets of opportunity.[138]As for the air war’s intensity over time, what started out as little more than 200 combat and combat‑support sorties a day eventually rose to over 1,000 sorties a day by the time of the cease‑fire.[139]All told, 28 percent of the sorties flown were devoted to direct attack, with 12 percent going to SEAD, 13 percent to attacks against dispersed enemy forces in Kosovo, 16 percent to defensive counterair patrols, 20 percent to inflight refueling, and 11 percent to other combat support missions (including AWACS, Joint STARS, ABCCC, EC‑130 jammers, airlift, and combat search and rescue).[140]Figure 3.4 shows the breakout of U.S. sorties flown by aircraft type.

According to the final air operations database later compiled by Hq USAFE, 421 fixed targets in 11 categories were attacked over the 78‑day course of Allied Force, of which 35 percent were believed to have been destroyed, with another 10 percent sustaining no damage and the remainder suffering varying degrees of damage from light to severe. The largest single fixed‑target category entailed ground‑force facilities (106 targets), followed by command and control facilities (88 targets) and lines of communication, mostly bridges (68 targets). Other target categories included POL‑related facilities (30 targets), industry (17 targets), airfields (8 targets), border posts (18 targets), and electrical power facilities (19 targets). In addition, 7 so‑called counterregime targets were assessed as having sustained overall light damage. Finally, 60 targets were associated with Serb air defenses in two categories (radars and launch equipment), out of which two of three SA‑2s, 11 of 16 SA‑3s, and 3 of 25 STRAIGHT FLUSH radars associated with the SA‑6 were assessed as having been destroyed.[141]

Figure 3.4–USAF Sortie Breakdown by Aircraft Type

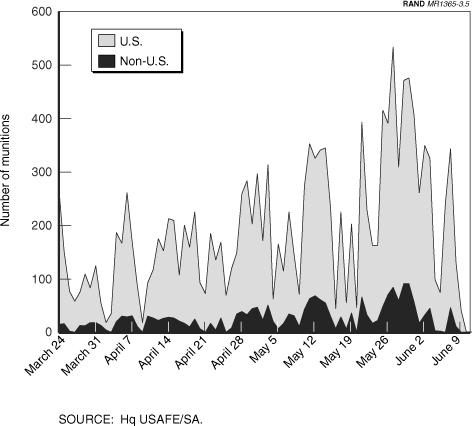

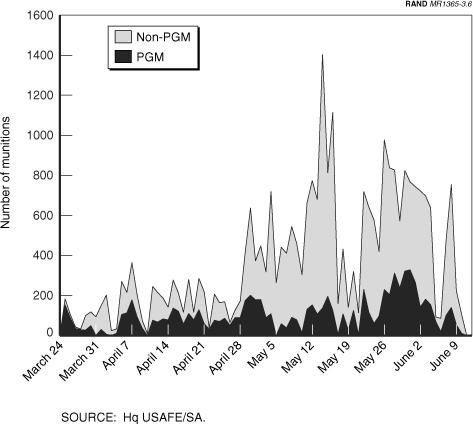

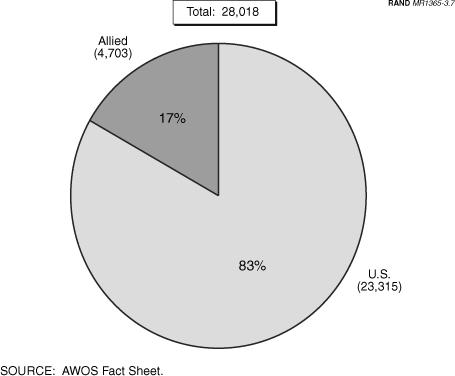

As for the 28,018 munitions (excluding TLAMs) that were expended altogether, a full one‑third were general‑purpose Mk 82 unguided bombs dropped by B‑52s and B‑1s during the war’s final two weeks. Figure 3.5 presents the trend of U.S. and allied munitions expenditure over the 78‑day course of Allied Force. Figure 3.6 shows the number of precision weapons and nonprecision weapons delivered daily over the same period. Of that number, the United States delivered 83 percent, or all but 4,703 (see Figure 3.7).

In a telling reflection of the sparse intelligence available on the location of enemy SAMs and of NATO’s determination to avoid losing even a single aircrew member, some 35 percent of the overall effort (including both direct attack and mission support) was directed against enemy air defenses. Thanks in part to the weight of that effort, only two allied aircraft were downed and not a single friendly fatality was incurred, save for two AH‑64 pilots who were killed in a training accident in Albania (see Chapter Five for more on these incidents). Even at that, however, enemy SAMs were effectively suppressed but not often destroyed.

Figure 3.5–U.S. and Allied Ground‑Attack Munitions Expended (excluding TLAM)

Figure 3.6–U.S. and Allied Munitions Expenditures by Type

Figure 3.7–Total Numbers of Munitions Expended

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1200;