PRELUDE TO COMBAT

Operation Allied Force, largely prompted by humanitarian concerns, was a response by the United States and NATO to the steadily mounting Serb atrocities that were being committed against the ethnic Albanians who made up the vast majority of Kosovo’s population. At bottom, the crisis was rooted in a centuries‑long history of Balkan strife.[3]Its more immediate origins could be traced back to a decade before, when the disintegration of the Yugoslav

Federation began during the waning years of the cold war.[4]Under the iron rule of Yugoslavia’s independent communist leader, Marshal Josip Broz Tito, Kosovo had remained an autonomous and self‑governing province of Serbia for nearly 40 years, and members of its largely ethnic Albanian populace were able to live a reasonable approximation of normal lives. Once communist rule began to unravel in the late 1980s after Tito’s death, however, the Serb minority in Kosovo reacted forcefully against what they perceived to be willful discrimination against them by the Kosovar Albanian authorities.

After winning an election in 1989 in which he played heavily on Serb feelings of mistreatment, Milosevic decreed an end to Kosovo’s autonomy, imposed Serb rule, and unleashed a resurgence of ethnic violence throughout the former Yugoslav Federation that, by 1995, had caused more than a quarter of a million innocent citizens to lose their lives in a renewed Balkan civil war. That, in turn, gave rise to a group of Kosovar Albanian nationalists who espoused the use of violence in pursuit of Kosovar independence, ultimately spawning a militant émigré group called the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA, or UCK in Albanian, for Ushtria Clirimtare e Kosoves ), whose members began waging a partisan war against the Serb army and police units that controlled the increasingly conflicted province.

In February 1998, in an escalating wave of reprisals against the rearguard actions of this nascent band of ethnic Albanian guerrillas, a unit of the Yugoslav interior ministry police, or MUP (for Ministerstvo Unuprasnij Poslava ), counterattacked in force against the KLA in the Drenica region of Kosovo, wantonly killing some 80 Kosovar Albanian civilians in the process. In response, U.S. special envoy Richard Holbrooke was sent to Belgrade by the Clinton administration to beseech Milosevic to desist from further acts of violence against Kosovar civilians. Milosevic refused. Later, in early fall of 1998, some 30,000 Kosovar civilians were forced to flee their homes in the wake of resurgent Serb pillaging and terrorizing of the Kosovo countryside. That renewed violence prompted the passage on September 23, 1998, of UN Security Council Resolution 1199 warning of an “impending humanitarian catastrophe” and calling for an immediate halt to the escalating strife in Kosovo. The following month, the Clinton administration again dispatched Holbrooke to Belgrade in a bid to persuade Milosevic to agree to negotiations on Kosovar autonomy and to accept a presence in Kosovo of unarmed international monitors from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) to verify Serb compliance with Resolution 1199.

In the end, Milosevic assented to negotiations and agreed to permit an OSCE verification mission to enter Kosovo after the endorsement by the North Atlantic Council (NAC), the political arm of NATO, of an Activation Order (ACTORD) laying the groundwork for NATO air attacks against Serb military targets as an inducement. The mission, headed by U.S. diplomat William Walker, aimed at ensuring that the KLA’s partisans remained in the mountains and that the Yugoslav army, or VJ (for Vojska Jugoslavskaya ), remained in its garrisons. Air surveillance for this OSCE presence was to be provided by NATO, and a NATO extraction force began forming in Macedonia to withdraw the OSCE observers under armed protection in case events turned sour enough to endanger their safety.

Before long, however, the OSCE monitors found themselves watching helplessly as the Serb killing of Kosovar Albanians continued at a slow but steady rate. In response, NATO declared that it would take “all steps,” including air strikes if necessary, to compel Serb compliance in bringing about a settlement in Kosovo. Meantime, as Holbrooke continued shuttling between Belgrade and Washington, Kosovo remained all but absent from the Clinton administration’s list of priorities. Among other preoccupations closer to home, final preparations for the president’s impeachment trial in the House of Representatives had entered full swing by December 1998, and tensions with Iraq were about to escalate into the launching of Operation Desert Fox that same month, a four‑day mini‑air operation waged by U.S. and British forces in what turned out to have been an almost entirely symbolic and ineffectual response to Saddam Hussein’s earlier summary decision to refuse further cooperation with UN arms inspectors.

The trigger event that finally spurred the Clinton administration into action with respect to Kosovo occurred on January 15, 1999, when MUP and Serb paramilitary troops in hot pursuit of KLA fighters entered the village of Racak and proceeded to slaughter 45 hapless ethnic Albanian civilians. Ambassador Walker personally traveled to Racak the next day to view the carnage, calling it a crime against humanity and all but blaming Milosevic by name for having ordered it. Two days later, the Yugoslav government, in response, declared Walker persona non grata and issued an expulsion order, which Walker ignored.[5]The Racak massacre signaled the beginning of the end to any further active role for the OSCE monitors, who were now increasingly at physical risk themselves and who were ultimately withdrawn less than a week before the commencement of Operation Allied Force. It turned out to be a serious miscalculation on Belgrade’s part. What Milosevic may have thought was “just another village” proved to be one too many as far as the United States and NATO were concerned.[6]The event marked the beginning of the final countdown toward NATO’s ultimate decision to proceed with Allied Force. On January 30, the NAC approved the launching of NATO air attacks against Serbia if the Serb leaders continued to refuse negotiations with their Kosovar counterparts.

On February 6, the Contact Group (made up of representatives from France, Germany, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States), prodded by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, summoned Serb and KLA representatives to the Rambouillet chateau on the outskirts of Paris for a last‑chance round of talks aimed at producing an overarching settlement for Kosovo. Those talks ended without agreement on February 23. Further talks began in Paris on March 15. During the latter negotiations, Albright delivered an ultimatum to the Serbs and Kosovars alike that, as an incentive, offered to contribute 28,000 NATO peacekeepers, including 4,000 U.S. troops, to police any negotiated settlement. Three days later, the KLA signed a peace accord aimed at giving Kosovo broad autonomy within Serbia. The day after, however, Serbia refused to sign, insisting that it would not even consider the idea of foreign troops on Kosovo soil. More ominously yet, on the very same day that this second round of talks began, Milosevic ordered a major escalation of the buildup of VJ forces both within and immediately adjacent to Kosovo that had begun the previous month, in a clear sign that a major move against the KLA and against ethnic Albanian civilians was imminent.

By all indications, Milosevic did not enter the Rambouillet process with any intent to negotiate seriously. On the contrary, in all likelihood he saw it as presenting a perfectly timed opportunity to position himself to launch Operation Horseshoe (Potkova ), as his incipient ethnic cleansing campaign was code‑named. By that point, he most likely fully anticipated that NATO would eventually bomb him, much as U.S. and British forces did in a token manner against Iraq two months previously in Desert Fox. Probably key to Milosevic’s strategy was an underlying belief that he could take at least as much measured pain from a symbolic NATO air operation as Saddam Hussein had endured from Desert Fox. That belief most likely hinged on an associated conviction that NATO’s limited tolerance for bombing would run out in short order and that he would then have Kosovo all to himself, with no further outside meddling by NATO, OSCE, or any other foreign peace‑enforcement entities, and with no Kosovar Albanians. As if to bear that out, not only did Belgrade reject NATO’s peace proposal outright, it simultaneously launched a new campaign of burning and pillaging by some 40,000 VJ troops in the central Drenica region of Kosovo, using tanks, heavy artillery, and mortar fire against dozens of villages. In the process, VJ and MUP forces destroyed three of seven known regional headquarters of the KLA and forced thousands of ethnic Albanian civilians to flee. In the wake of that renewed assault, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees reported 240,000 internally displaced persons in Kosovo, including 60,000 rendered homeless in just the preceding three weeks.

The refugee crisis quickly assumed all the earmarks of a humanitarian disaster. President Clinton ordered Holbrooke back to Belgrade on March 22 in an eleventh‑hour bid to persuade Milosevic to desist from further ravaging of Kosovo or else face NATO bombing attacks. Holbrooke was instructed to warn Milosevic that NATO was preparing air and missile strikes that would destroy much of Yugoslavia’s military infrastructure. Milosevic was further warned that the targets of those attacks would be not just in Kosovo but in Serbia as well.[7]Holbrooke made no attempt to bargain and stressed to Milosevic that he was in Belgrade solely to deliver a message. At the end of a four‑hour meeting, he was rebuffed.

At that point, with the gauntlet thrown down by Holbrooke, U.S. officials presented NATO’s ambassadors with a final proposed bombing plan against Serbia, the declared goals of which were a verifiable halt to ethnic cleansing and atrocities on the ground in Kosovo; a withdrawal of all but a token number of VJ, MUP, and paramilitary troops from Kosovo; the deployment of an international peacekeeping force in Kosovo; the return of refugees and their unhindered access to aid; and the laying of groundwork for a future settlement in Kosovo along the lines of the Rambouillet terms of reference.[8]Commenting on the threatened campaign, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR), U.S. Army General Wesley Clark, warned that “if required, we will strike in a swift and severe fashion.” General Klaus Naumann, the chairman of NATO’s Military Committee, added that Milosevic was “severely mistaken” if he believed that NATO would engage merely in pinprick attacks and then await his response.[9]

Earlier, when the allies had empowered NATO Secretary General Javier Solana to authorize air strikes on January 30, the declared intent was to conduct limited raids over 48 hours and then pause to encourage Milosevic to reconsider. The plan this time was for a wider range of targets to be hit and for a longer operation aimed at causing considerable infrastructure damage. In an eleventh‑hour bid to marshal public support for the impending air effort, President Clinton made an appeal, in a televised speech at a labor union luncheon on the day before the bombing commenced, beseeching the American people to support his actions in coming to grips with NATO’s looming Kosovo predicament.[10]

To be sure, planning for an air operation of some sort against Serbia had begun as early as June 1998. Initial plans were for an option called Operation Nimble Lion, which would have pitted a substantial number of U.S. and allied aircraft against some 250 targets throughout the former Yugoslavia.[11]This option was developed wholly within U.S. channels by the 32nd Air Operations Group at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, at the behest of USAF General John Jumper in his capacity as commander, United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), in response to a directive from Clark in his capacity as commander in chief, U.S. European Command (USEUCOM). A separate plan called Concept of Operations Plan (CONOPLAN) 10601 was later developed by NATO and approved by the NAC. Although there was some overlap between these two plans, the thrust of each was different. Nimble Lion would have hit the Serbs hard at the beginning, whereas 10601 entailed a gradual, incremental, and phased approach. The latter ultimately became the basis for Operation Allied Force.

Two closely related U.S. joint task force (JTF) planning efforts called Operations Flexible Anvil (commanded by U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Daniel Murphy, commander of the 6th Fleet) and Sky Anvil (commanded by USAF Lieutenant General Michael Short, commander of the 16th Air Force at Aviano Air Base, Italy) followed in the summer of 1998.[12]Those efforts were terminated when Milosevic initially agreed to a cease‑fire after his October 5–13 talks with Holbrooke.[13]In all, General Jumper later reported that by the onset of Allied Force, no fewer than 40 air campaign options had been generated and fine‑tuned.[14]Those options were said to have included some that were at least implicitly critical of the proposed use of NATO air power without a supporting ground threat to encourage enemy troops to assemble and maneuver so they might be more easily targeted and attacked from the air.

In the end, however, the plan ultimately agreed to by NATO expressly ruled out any backstopping by ground forces for two avowed reasons. The first had to do with identified logistic difficulties, the anticipated challenge of the terrain, and poor access and basing opportunities. The second, and far more pivotal, reason entailed the Clinton administration’s concern over lack of congressional support for such an option and the presumed unwillingness on the part of the American people and the NATO allies to accept combat casualties, reinforced by a near‑certainty that the allies would not buy into a ground option. All planning, moreover, took for granted that NATO’s most vulnerable area (or “center of gravity”) was its continued cohesion as an alliance. In light of that, any target or attack tactic deemed even remotely likely to undermine that cohesion, such as the loss of friendly aircrews, excessive noncombatant casualties, excess collateral damage to civilian structures, or anything else that might undermine domestic political support or cause a withdrawal of public backing for the bombing effort, was to be most carefully considered–if not avoided altogether.

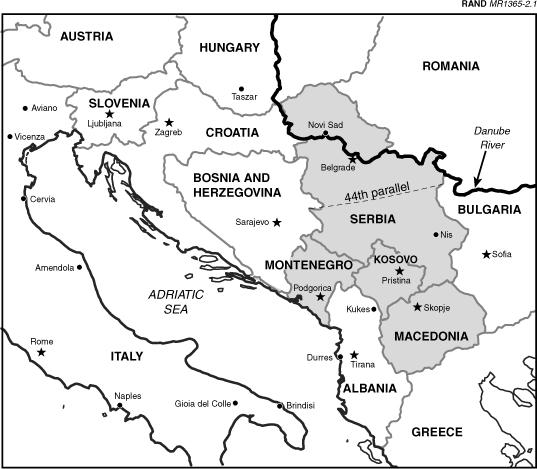

NATO’s final plan was conceived from the start as a coercive operation only, with the implied goal of inflicting merely enough pain to persuade Milosevic to capitulate. Its first phase, against only 51 approved integrated air defense system (IADS) targets and 40 approved punishment targets out of 169 in NATO’s Master Target File, entailed attacks against a combination of enemy air defenses and fixed army installations that aimed at softening up Yugoslavia’s IADS and demonstrating NATO’s ability to conduct precise air attacks with a minimum of unintended damage. The second phase envisaged attacks against military targets mainly, though not exclusively, below the 44th parallel, which bisected Yugoslavia well south of Belgrade (see Figure 2.1). Only in the third phase, if need be, would the bombing go in earnest after military facilities north of the 44th parallel and against targets in Belgrade itself.[15]NATO had approved this three‑phase plan in principle the preceding October as a part of its ACTORD and had handed the keys for Phase I to Solana on January 30. Approval by the NAC of Phases II and III, however, would come only after the air effort began.

Figure 2.1–Allied Force Area of Operations

For his part, General Clark had called for punitive air strikes against Yugoslavia as early as January 1999, in response to the Serb massacre of 45 Kosovar Albanians near the town of Racak just days before. Persistent pressures from within NATO to explore a diplomatic solution, however, outweighed that recommendation for the early use of force. The resulting delay gave Milosevic time to bolster his forces, disperse important military assets, hunker down for an eventual bombing campaign, and lay the final groundwork for the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo. Owing to that delay, NATO lost any element of surprise that may otherwise have been available.[16]

In the end, Operation Allied Force came just 10 days short of NATO’s 50th anniversary. The Clinton administration did not seek a UN Security Council resolution approving the air attack plan, since it knew that Russia and China had both vowed to veto any proposal calling for air strikes.[17]NATO’s going‑in expectation was that the bombing would be over very quickly. Indeed, so confident were its principals that merely a token bombing effort would suffice to persuade Milosevic to yield that the initial attack was openly announced in advance, with U.S. officials conceding up front that it would take a day or more to program all of the TLAMs to hit some 60 planned aim points.[18]Only at the last minute did NATO’s political leaders give Secretary General Solana authority for what one NATO official called a “much more diverse target list, a more intensive pace of operations, and an expanded geographical zone.”[19]Once under way, the slowly escalating air effort put the United States into two simultaneous regional conflicts (the other being Operations Northern and Southern Watch against Iraq) for the first time since World War II. It also made for a uniquely demanding test for American air power and became the most serious foreign policy crisis of the Clinton presidency.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1127;