Black Shield

On March 22, 1965, Brig Gen Jack Ledford, Director of the CIA’s Office of Special Activities, briefed Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance on Project Black Shield – the planned deployment of Oxcart to Okinawa, in response to the increased SA‑2 threat facing U‑2s and Firebee drone reconnaissance vehicles. Secretary Vance was willing to make $3.7 million available to provide support facilities at Kadena AB, which were to be ready by the fall of 1965. On June 3, 1965, Secretary of Defense McNamara consulted with the Under Secretary of the Air Force on the build‑up of SA‑2 missile sites around Hanoi and the possibility of substituting A‑12s for the vulnerable U‑2s on recce flights over the North Vietnamese capital. He was informed that Black Shield could operate over Vietnam as soon as adequate aircraft performance was validated.

On November 20, 1965, Bill Park completed the final stage of Project Silver Javelin, the Oxcart validation process, with a maximum‑endurance flight of six hours and 20 minutes, during which time he demonstrated sustained speeds above Mach 3.2 at altitudes approaching 90,000ft. Four A‑12s were selected for Black Shield operations, Kelly Johnson taking personal responsibility for ensuring that the aircraft were completely “squawk‑free.” On December 2, 1965, the highly secretive 303 Committee received a formal proposal to deploy Oxcart operations to the Far East. The proposal was quickly rejected, but the Committee agreed that all steps should be taken to develop a quick‑reaction capability for deploying the A‑12 reconnaissance system within a 21‑day period anytime after January 1, 1966.

A rearward‑facing cine camera was mounted behind the cockpit of the three Black Shield Oxcarts, the idea being to film SA‑2 attacks, although it isn’t known if any footage was ever captured during at least three of the known incidents. In this picture the aircraft is seen at speed and altitude – note the position of the fully retracted spike to produce the maximum inlet capture area. (Roadrunners Internationale)

Throughout 1966, numerous requests were made to the 303 Committee to implement the Black Shield Operations Order, but all requests were turned down. A difference of opinion had arisen between two important governmental factions that advised the Committee: the CIA, the Joint Services Committee, and the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board favored the deployment; but Alexis Johnson of the State Department, Robert McNamara and Cyrus Vance of the Defense Department opposed it.

Whilst the political wrangling continued, mission plans and tactics were prepared to ready the operational “package” for deployment should the Black Shield plan be executed. Deployment timing was further cut from 21 to 11 days, and the Okinawa‑based maintenance facility was stocked with support equipment. To further underwrite the A‑12’s capability to carry out long‑range reconnaissance missions, Bill Park completed another nonstop sortie, this time of 10,200 miles in just over six hours on December 21, 1966. But misfortune struck the program again on January 5, 1967, when, due to a faulty fuel gauge, Article 125 was lost some 70 miles short of Area 51. The CIA pilot Walt Ray ejected safely, but tragically was unable to gain seat‑separation and was killed on impact with the ground.

In May 1967, the National Security Council was briefed that North Vietnam was about to receive surface‑to‑surface ballistic missiles. Such a serious escalation of the conflict would certainly require hard evidence to substantiate such a claim; consequently President Johnson was briefed on the threat. DCI Richard Helms again proposed that the 303 Committee authorize deployment of Oxcart, as it was ideally equipped to carry out such a surveillance task on the grounds of having both superior speed and altitude to U‑2s and pilotless drones, as well as a better camera. President Johnson approved the plan and in mid‑May an airlift was begun to establish Black Shield at Kadena AB.

At 0800hrs on May 22, 1967, Mele Vojvodich departed from Area 51 in Article 131 and headed west across California for his first refueling. Having topped‑off, he accelerated to high Mach toward the next Air Refueling Control Point near Hawaii. A third rendezvous took place near Wake Island to ensure that he had enough reserve fuel to divert from an intended landing at Kadena AB to either Kunsan AB in South Korea or Clark AFB in the Philippines, should the weather over Okinawa deteriorate. When Vojvodich arrived at Kadena AB, however, the weather was fine and he let down for a successful landing after an uneventful flight of just over six hours’ duration.

Two days later, Jack Layton set out to repeat Vojvodich’s flight in Article 127 (60‑6930); and Jack Weeks followed in Article 129 (60‑6932) on May 26. However, due to INS and radio problems, Weeks was forced to divert into Wake Island. An Oxcart maintenance team arrived in a KC‑135 from Okinawa the following day to prepare Article 129 for the final “hop” to Kadena AB. After completing the journey, Weeks’ aircraft was soon declared fit for operational service along with Articles 127 and 131. As a result, the Detachment was declared ready for operations on May 29 and, following a weather reconnaissance flight the day after, it was determined that conditions over North Vietnam were ideal for an A‑12 photo‑run.

Project Headquarters in Washington, DC then placed Black Shield on alert for its first ever operational mission. Avionics specialists checked various systems and sensors, and at 1600hrs Mele Vojvodich and back‑up pilot Jack Layton attended a mission alert briefing that included such details as the projected take‑off and landing times, routes to and from the target area, and a full intelligence briefing of the area to be overflown. At 2200hrs (12 hours before planned take‑off time) a review of the weather confirmed the mission was still on, so the pilots went to bed to ensure they got a full eight hours of “crew rest.”

They awoke on the morning of the 31st to torrential rain, but the two pilots ate breakfast and proceeded to prepare for the mission. Despite local meteorological conditions, the weather over “the collection area” was good, so at 0800hrs Kadena received a final clearance from Washington, DC that Black Shield flight BX001 was definitely “on.” Following brief medical checks, the two pilots donned their S‑901 full pressure suits and began breathing 100 percent pure oxygen to purge their bodies of potentially harmful nitrogen. By taxi‑time, the rain was falling so heavily that a staff car had to lead Vojvodich’s aircraft from the hangar to the end of the main runway. After lining up for what would be the first instrument‑guided take‑off, on cue both afterburners were engaged and Article 131 accelerated rapidly down the runway to disappear completely into the rain and then upward, through the drenching clouds.

The only pictures to have emerged to date of Oxcart’s participation in Black Shield are these two grainy images taken from 8mm black and white cine film shot, ironically, by the CIA’s station head of security. (Roadrunners Internationale)

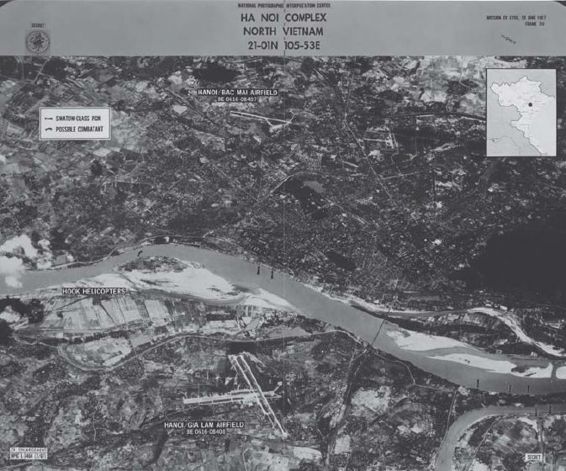

A few minutes later, Article 131 burst through cloud and climbed to 25,000ft to top‑off its tanks from the waiting KC‑135Q tanker. Once disengaged from the tanker’s boom, Vojvodich accelerated and climbed to operational speed and altitude having informed Kadena (“home‑plate”) that the aircraft systems were running as per the book and the backup services of Jack Layton would not be required. Vojvodich penetrated hostile airspace at Mach 3.2 and 80,000ft during a so‑called “front door” entry over Haiphong, then continued over Hanoi before exiting North Vietnam near Dien Bien Phu. A second air refueling took place over Thailand, followed by another climb to speed and altitude, and a second penetration of North Vietnamese airspace made near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), after which Vojvodich recovered the aircraft back at Kadena after three instrument approaches in driving rain. The flight had lasted three hours and 40 minutes and, during an interview with this author, the pilot claimed that several SA‑2s were fired at the aircraft but all detonated above and well behind the target. (This remains a matter of controversy to this day, for when the CIA’s program manager for Oxcart, John Parangosky, wrote his classified paper about the project under the pseudonym Thomas P. McIninch, shortly after its termination, he asserted that no hostile action was taken against any of the first seven missions.) Notwithstanding, upon safe arrival back at the “barn” the film from the Type I camera was removed and flown by special courier aircraft to the Eastman Kodak plant in Rochester, New York, for processing. The processed imagery was then sent to Photo Interpreters at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), located within the Washington Navy Yard, who then prepared the Initial Photographic Intelligence Report (IPIR). The results were astounding: in all, Article 131’s camera had successfully photographed ten priority target categories including 70 of the 190 known SAM sites.

Frame 761, analysed at NPIC, was taken during mission BX6706 on 30 June 1967, by Jack Weeks flying Article 129 at 82,000ft. The area surveillance capability of the Type I camera is readily apparent, as is its resolution, enabling two helicopters to be both located and identified as large cargo‑hauling Mil Mi‑22 Hooks. (CIA via David Robarge)

Jack Layton’s first operational flight had to be aborted. All had gone well until he entered Deep Work, the refueling track just southwest of Okinawa, and plugged into the tanker’s refueling boom. The boom operator’s first remarks as the A‑12’s fuel tanks began to fill were, “You don’t want to go supersonic with this aircraft, Sir.” The puzzled A‑12 pilot enquired why, there being no cockpit indications that supported such a remark and the aircraft seemed to be handling well. “I don’t think you’ll want to go fast, Sir,” the boom operator insisted, “because the left side of your aircraft is missing.” After further consultation with the boom operator and other tanker crewmembers who went aft to view the unusual sight, Jack decided that prudence should dictate that he abort his first important mission – however reluctantly. As he turned back to Kadena, an F‑102 interceptor was scrambled from Naha AB, Okinawa, to serve as escort back to “home‑plate” in the event of controllability problems. As the Delta Dagger drew alongside the crippled Oxcart, the F‑102 pilot reported that the A‑12 had lost practically all of its left chine panels from nose to tail. In addition, large panels on the top of the wing (which also covered the top side of the wheel well) had also disappeared, allowing the chase pilot to see right through part of the aircraft’s left wing. As some of these panels had broken loose, at least one had impacted the top of the left rudder, causing even more damage.

This series of shots were all taken during mission BX6847 over North Korea and aptly demonstrate the amazing capabilities of the Type I camera – the very essence of what the A‑12’s mission was designed to generate. From 80,000ft, a film frame measuring 27in×6in captured a ground swath 72 miles wide. At nadir Hwangju Air Base was filmed; Photo Interpreters could then enlarge areas of interest many times to take a detailed look – in this instance, MiG‑17s on the apron of the main runway. An SA‑2 battery was filmed also close to nadir where together the camera and film produce a resolution of 1ft. Then, nearly 30 miles to one side of the Oxcart’s track with a ground resolution of 2–3ft, is Yongbyon, North Korea’s nuclear plant. (National Archives via Talent‑Keyhole.com)

As the two aircraft descended below 20,000ft, they dipped into clouds and the A‑12’s cockpit fogged‑up so badly that Jack was unable to see his hand in front of his face, let alone read his flight instruments. He quickly called for the F‑102 pilot to report the A‑12’s attitude, since he was becoming very concerned that it might depart its flight envelope by stalling or diving. Relieved that he had remained within normal flight parameters, Jack managed to climb back out of the clouds. By turning the cockpit temperature control to full‑hot, he managed to eliminate the humidity that had caused the fogging, but the hotter‑than‑normal cockpit soon became extremely uncomfortable. Nevertheless, he was able to safely recover back at Kadena without further incident.

During the first three months of Black Shield operations, nine missions were successfully completed. However, according to Parangosky, mission BX6705 flown by Jack Layton in Article 127 on June 20, 1967 was the first occasion that an Oxcart was successfully tracked on enemy radar. Bearing in mind all the time and vast expense that had been invested in reducing the aircraft’s RCS, this must have caused considerable consternation both back at CIA headquarters and within the Skunk Works.

By mid‑July, Black Shield imagery had determined with a high degree of confidence that there were no surface‑to‑surface missiles in North Vietnam. But Oxcart flights were becoming invaluable, providing important intelligence to mission planners about the enemy’s Order of Battle, as well as high‑quality bomb‑damage assessment imagery. The problem was the protracted timelines involved in processing the intelligence from film download, to receipt of the processed imagery and the IPIR.

To speed up the process, the 67th Reconnaissance Technical Squadron (Recce Tech), at Yokota AB, Japan, were also provided with the necessary skills and equipment to undertake the work. So following an enormous amount of hard work and dedication, on August 18, 1967, the 67th RTS was recertified as Overseas Processing and Interpretation Center – Asia (OPIC‑A). This action provided theater commanders with Black Shield imagery and an IPIR within 24 hours of a mission. Subsequently, from BX6722, flown by Jack Weeks in Article 129 on September 16, 1967, this became the standard operating procedure throughout the remaining period of Black Shield.

From September to the end of December 1967, the three Black Shield‑operated A‑12s completed 11 operational missions – the highest period of activity being reached in October, when seven sorties were flown. Frank Murray’s first operational mission, BX6727 (a so‑called “double‑looper”), was flown on October 6 in Article 131. His first photo‑run at an altitude above 80,000ft on a track deep into North Vietnam went well. But as he was about to turn off his cameras before heading south toward Scope Pearl, the Oxcart air refueling track located over Thailand, his left engine started vibrating, followed shortly thereafter by a left inlet unstart. Frank recalled: “I had my hands full for a while. In fact, I ended up having to shut the engine down. I increased power on the good engine and flew it at maximum temperature for about an hour before I hooked up with the tanker. Because of the shut‑down engine, I decided to divert into Takhli and the tanker crew relayed messages back to Kadena that I was diverting. Because I kept my radio calls to a minimum for security reasons, I didn’t identify myself to the Takhli air traffic controllers until I was on final approach for landing. I landed without incident, but inadvertently screwed up a complete F‑105 strike mission launch when I jettisoned the big brake ’chute on the main runway. I turned off the runway and sat there with the engine running and asked that the base commander come out to the aircraft as there were certain things I had to tell him. My presence was causing a pandemonium of curiosity; there was this most unusual black aircraft with no markings, the like of which nobody on that base had ever seen before, that had dropped in completely unannounced, disrupting a major operation and its pilot insisting on the base commander coming out to see him! While this was going on guys on base with cameras were clicking away like mad. Eventually they sent out the Thai base commander which was no good because I wanted the US base commander. He eventually arrived and (despite all my disruptions to his war operations) was extremely helpful.”

After Frank’s aircraft had been safely tucked away in an “Agency” U‑2 facility on the base, the Air Force Security Police had a “field day” confiscating the opportunists’ film. An inspection of the left engine revealed that most of its moving parts had been “shucked like corn from the cob” and were lying in the tail pipe and the afterburner. A recovery crew flew in with a spare engine, but Article 131 had also sustained notable damage to the nacelle and to some of its nearby electrical wiring. It was decided that the jet would have to be flown back to Kadena AB “low and slow” on October 9. Frank explained: “I got airborne and headed off south over the Gulf of Thailand, where I picked up an F‑105 escort that led me out over South Vietnam. There the escort was changed and the F‑4s that had covered me and my tanker broke off to return to their base. We then made our way via the Philippines, where I picked up another tanker which led me back to Kadena.”

Whilst Frank was dealing with the in‑flight emergency over North Vietnam, his attention had been diverted away from switching off the photographic equipment to the more pressing priority of controlling the aircraft. As he turned south, his still‑operating camera had taken a series of oblique shots into China. Close analysis of those photos revealed eight tarpaulin‑covered objects among a mass of other material along the large main rail link between Hanoi and Nanking. Further photo interpretation ascertained that the “tarps” were flung over rail flatcars in an attempt to hide 152mm self‑propelled heavy artillery pieces. A great mass of other war material in the rail yards had been assembled for onward movement to North Vietnam during the oncoming winter season when low clouds and poor visibility would hamper US bombing efforts to halt southbound supply lines. A timely and highly valuable piece of strategic intelligence, gained on the back of Frank’s troubled sortie, had given intelligence specialists a unique opportunity to track the further movement of those guns and supplies, obviously intended for use in future offensive actions.

During sortie number BX6732, flown in Article 131 by Denny Sullivan on October 28, 1967, the pilot received indications on his RHAW receiver display of almost continuous radar activity focused on his A‑12, whilst both inbound and outbound over North Vietnam. This culminated in the launch of a single SA‑2 – according to Parangosky, the first ever at an Oxcart. Two days later, during the course of sortie BX6734, Sullivan was flying Article 129 high over North Vietnam when on the first eastbound pass, between Haiphong and Hanoi, his RHAW receiver display indicated that two SA‑2 sites were tracking him and preparing to engage the Oxcart; but neither launched. However, during the second pass, whilst heading west and in the same area as earlier, at least six missiles were fired from sites around the capital. Looking through his rear‑view periscope, Sullivan reported seeing six vapour trails climb to an estimated 90,000ft behind the aircraft and then arc toward it. He reported observing four missiles, one as close as 100–200yds away (when flying at speeds of one mile every 1.8 seconds, that really is extremely close), and three detonations, all behind the aircraft – six missile contrails were captured on the Type I camera’s film. After recovering the aircraft back at Kadena without further incident, a post‑flight inspection revealed that a tiny piece of shrapnel had penetrated the lower wing fillet of his aircraft and become lodged against the support structure of the wing tank – history would prove this to be the only enemy “damage” ever inflicted on a “Blackbird.”

Denny Sullivan has the questionable distinction of being the only Oxcart pilot to have definitely been attacked twice by SA‑2s, during separate Black Shield missions – BX6732 and BX6734. (CIA)

The North’s missile activity caused DCI Richard Helms to order the temporary suspension of all Black Shield flights, during which time those involved were given the opportunity to review and re‑evaluate procedures and routes. In fact, it was more than a month before operational flights resumed and their reintroduction saw a temporary switch of target areas – for the first time, the “collection area” was Cambodia. Black Shield missions BX6737 and 6738 both utilized Article 131 and were flown by Mele Vojvodich on December 8, 1967 and by Jack Layton two days later. However, during the first four‑hour sortie, cloud cover obscured four of the seven special search areas for troop concentrations in the extreme northeast part of Cambodia, including both primary targets – although limited troop activity was detected where the Tonle San River crosses the Cambodia/Laos border, together with the regrading of the natural‑surface runway at Ban Pania Airfield. In contrast, the virtually cloud‑free conditions experienced by Jack Layton on December 10 enabled his Type I camera to gather valuable photography on all seven priority search areas – although this was secured not without issue. As Jack recalled, the INS caused the aircraft to overshoot the planned track during turns, causing him to “penetrate the bamboo curtain.” After turning south and getting back to an approximate course toward Scope Pearl, the air refueling track over Thailand, he had difficulty finding the tankers due to low cloud and poor visibility: “I got the aircraft up in a bank to search for the tankers but the visibility from an A‑12 is very poor; you can look down and see the ground but you can’t look inside the turn because of the canopy roof. I’d just about reached the point where I was about to divert to Takhli due to the lack of fuel when I finally saw the tankers. We got together and I was able to complete the mission even though the INS wasn’t working.”

On December 15 and 16, overflights of North Vietnam resumed. To limit exposure to the SA‑2 risk, mission planners re‑orientated the route, moving the track from an east/west direction to a less productive south/north route. The next two missions, BX6739 and 6740, both adhered to the amended route and no SA‑2s were fired. However, when Jack Layton flew BX6842, reverting back to the earlier east/west route, on January 4, 1968, he was attacked by a single SA‑2, again during the second pass. On this occasion, the missile was launched with its Fan Song missile control radar in low PRF – a highly significant event, being the first known instance of a Soviet SA‑2 having been guided by information derived from the Fan Song operating in low PRF mode. The aircraft’s ECM equipment – Mad Moth and Blue Dog – was activated and the missile missed its intended target.

CLOSE SHAVE

Having been fired upon by a single SA‑2 Guideline SAM on 28 October 1967, Denis Sullivan had the very dubious privilege of being attacked by a salvo of missiles just two days later. Sullivan was maintaining an easterly heading in the vicinity of Hanoi at the time of the attack. The Type I camera carried by his Oxcart captured no fewer than six SA‑2 contrails on film and post‑flight inspection revealed that a tiny piece of shrapnel had actually penetrated the aircraft’s lower wing fillet, and become lodged against a support strut of the wing tank. This “close shave” would prove to be the nearest that any “Blackbird” would ever come to being shot down throughout its entire operating career.

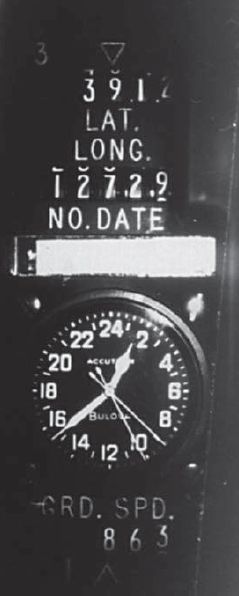

Details including latitude, longitude, time (GMT), and ground speed were applied to each photo frame via the data chamber. This enabled Photo Interpreters to establish the exact position of targets captured by the Type I camera. Note that this frame was taken during Black Shield mission BX6847; the coordinates are those of Wonsan Harbor, North Korea. The ground speed displayed only three digits – the thousandth column was omitted as this was considered “a given!” (National Archives via Talent‑Keyhole.com)

As 1967 drew to a close, a total of 41 Black Shield missions had been alerted by project headquarters, of which 22 were actually flown. Between January 1 and March 31, 1968, 17 missions were alerted, of which seven were flown: four over North Vietnam and three over North Korea. The main reason why scheduled flights were subsequently scrubbed was invariably poor weather conditions in the collection area.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1819;