Project Suntan

In the mid‑1950s and in parallel with Rainbow and Gusto, Johnson also began looking at a high‑altitude, Mach 2.5, non‑stealthy replacement for the U‑2, funded by the Air Force. Codenamed Project Suntan, it was proposed that the engines, built by Garrett, would be fueled by liquid hydrogen. On February 15, 1956, two Skunk Works design proposals, designated CL‑325‑1 and CL‑325‑2 and powered by the supersonic Rex III liquid hydrogen engine, were presented to the Air Force at Wright Field. But after extensive studies the Air Force became convinced that Garrett was incapable of building an engine as complex as that proposed. Consequently, on October 18, 1956, it issued a directive demanding that all work on both projects be stopped. However, as the result of an earlier meeting at the Pentagon with Lt Gen Donald Putt, head of Air Research and Development Command, Kelly offered to build two prototype hydrogen‑fueled aircraft powered by more conventional engines and have them delivered within 18 months of contract signing. Based upon the CL‑325, they would be capable of cruising at an altitude of over 99,000ft at a speed of Mach 2.5 and have a range of 2,500 miles.

Whilst the Air Force funded studies to verify Kelly’s proposal, they also invited both Pratt & Whitney and General Electric to submit proposals to build a hydrogen‑fueled engine. On May 1, 1956, two six‑month study contracts were signed, one with Pratt & Whitney for the engine and the other with the Skunk Works to evaluate airframe configuration and material options. As a result, contracts were awarded by the Air Force to the Skunk Works to produce four production aircraft and a single static test specimen; the design was designated CL‑400‑10.

On August 18, 1957, Pratt & Whitney had completed its first Model 304 engine and less than a month later, static tests were initiated. During October initial engine runs took place, followed by a second series in December. A second engine began tests on January 16, 1958 and on June 24 an improved engine, Model 304‑2, was delivered and tested.

All seemed to be running according to schedule: the Air Force had allocated $95 million to Project Suntan; Johnson had ordered no less than 2½ miles of aluminum extrusion for airframe production; the 304 engine continued to perform as planned; Air Products was constructing a large hydrogen liquefaction plant in Florida for fuel production, and MIT was working on an inertial guidance system. But over the next six months something continued to bother Johnson. Despite having successfully sold the aircraft to the Air Force, it was becoming increasingly apparent to him that the CL‑400’s severe range limitations couldn’t be designed out of the aircraft. The design fell short of its estimated original lift‑over‑drag ratio by 16 percent. Stretching the fuselage to increase fuel capacity would result in only a 3 percent increase in range. Pratt & Whitney estimated that no better than a 5–6 percent improvement in specific fuel consumption could be achieved with its Model 304 engine over a five‑year period of operation. Such low growth potential, coupled with the associated logistical problems of pre‑positioning liquid hydrogen to OLs, convinced Johnson that “the aircraft was a dog.” In March 1957, during a meeting with James Douglas Jr, then Secretary of the Air Force, and Lt Gen Clarence Irvin, deputy Chief of Staff for material, Kelly bluntly informed them of his misgivings and by the middle of that year, others were voicing similar concerns. In February 1958, and at Kelly’s insistence, Suntan was canceled. The Skunk Works returned almost $90 million and the Air Force perhaps lost an opportunity to wrestle the strategic reconnaissance overflight program away from the Agency. However, Project Suntan had provided Lockheed with an improved understanding of high‑speed flight as well as confirmation that hydrocarbon fuel, and not hydrogen, was the best choice for the proposed flight regime. It also provided Johnson with a major change of direction for Project Gusto.

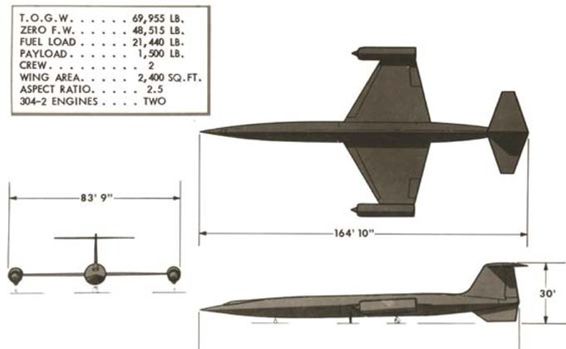

Although not part of Project Rainbow or Gusto, Project Suntan’s CL‑400 design provided Johnson with important insights into possible fuel and power plant options for a U‑2 replacement. (Lockheed Martin)

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1647;