SUMMARY. Depending upon the dog and the trainers, the drive‑work phase of protection training may last anywhere from two to eighteen months

Depending upon the dog and the trainers, the drive‑work phase of protection training may last anywhere from two to eighteen months. The time interval is not important. The task is accomplished and the dog is ready to progress only when it bites with a reasonably full mouth and great power, is reasonably well‑balanced between prey and defense, has absolutely no fear of being driven and stick‑hit and performs the most impressive courage test of which it is capable.

However, do not think that drive work is ever entirely finished. Throughout the dog’s working career, we will concern ourselves constantly with maintaining (and intensifying, if possible) our dog’s desire to bite. This task was vital early in its training, as we sought to establish its power. It may be even more important in field work, when we will begin, for the first time, to harness and control that power.

Protection: The Hold and Bark and the Out

A few years ago, while discussing the nature of control with a fellow trainer, we heard a story that illustrates the central problem of field work.

“I once had a wonderful young dog that bit like a lion. One day, very proudly, I showed him to an old‑time German dog trainer, and asked this man if my youngster was not truly a good dog. The old man said, ‘Show him to me again when he has three years and a clean bark and a clean out and still he bites like that, and then I will say that he is a good dog.’”

What the old man meant was simply this: A dog that bites with fire and bravery is not so rare. What is rare is an animal that has the strength to be strongly controlled by its handler, and still bite with fire and bravery.

Our German friend put his finger on an idea that we have since learned to be indisputably true. The acid test of a biting dog’s quality comes when, for the first time, it is forced to restrain itself during agitation. Many animals simply cannot support being controlled and corrected in bite work instead of being constantly encouraged. When the only load on their nerves comes from the person in front of them, they shine. But when pressure comes from behind, from their handlers (and some very hard‑looking dogs can be extraordinarily sensitive to pressure from this direction), they crumble. Where before they were sure under the stick, now they flinch. Where before they invariably bit with full mouths, now they chew and back off, rolling their eyes behind them and worrying about the out that they know is coming.

It seems that every generation of working dog trainers has an older generation behind it that is fond of telling how much harder the dogs of the old days were. We have heard these stories again and again. However, we are inclined to believe them, because we have seen how dogs were trained in the old days. They had to be hard.

For example, the old‑time method of teaching the hold and bark involved standing a decoy thirty‑one feet away, sending the dog at him and then correcting the animal very sharply with a long line when it hit thirty feet, six inches. This procedure is roughly analogous to knocking down in one instant a house that has been painstakingly constructed over a period of many months. All the dog’s life up to this moment, its trainers have urged it on in bite work, stoked the flames of its desire, never asking it to hold one bit of itself back. Now, in one instant, they change the rules, with rather unpleasant consequences for the animal.

However, this crude sort of method does work, if only in the sense that we can use it to easily teach the typical dog not to bite a person who is standing still. The shock and confusion produced by the unprecedented correction inhibit the animal, damping its excitement. The dog’s desire to bite brings it pain, so it powers down, resorting to other behavior. Because it feels unsure, it begins to bark, and the decoy rewards it for barking by moving and inducing the animal to bite. The lesson for the dog is clear: Cope with control and corrections by calming down, by stopping the flow of energy. Wait until conditions change, until control lifts, and then come into drive again.

We call this training for control by inhibition. It yields dogs that are one kind of animal when they are free to bite, and another, much lesser animal when they are restrained by control.

It is not difficult to train a dog this way. One needs only persistence and a heavy hand–and a hard dog. We can even produce a good dog by training with inhibition. But the difference between a good dog and a great dog is that a great dog is as calm, confident, aggressive and powerful when under control as when actually biting.

When a great dog is forbidden to bite, when commanded to “Out!” its drive does not diminish. It does not suddenly become less dog than it was a moment before. Instead, it energizes a new behavior, carrying all its energy intact as it outs and begins to bark powerfully.

We call this training for control by activation , and it depends upon making the animal understand perfectly what it is that it must do in order to get what it wants from us.

Nothing weakens the spirit like confusion, uncertainty and passive obedience to compulsion. The method of training for control by activation that we present here is designed to prevent both confusion and stress for the dog. By offering it clear, comprehensible alternatives that are both gratifying for it and also the result we desire, we avoid the necessity of using harsh compulsion to control the dog in bite work.

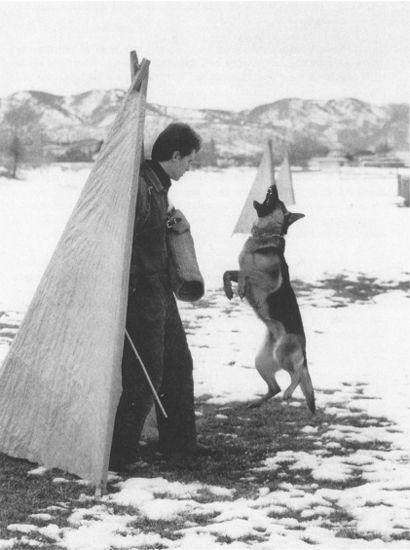

By training for control through activation rather than inhibition we can teach the dog to hold and bark powerfully and with spirit. (“Gitte”)

GOAL 1: The dog will hold and bark in front of a motionless agitator.

In Schutzhund bite work, there are really only four major skills that the dog must master: the hold and bark, the out, obedience on the protection field and the blind search. Of these four, the hold and bark and the out are by far the most important. Furthermore, the out is no more than an elaboration on the hold and bark–it follows quite naturally.

Therefore, we believe that the hold and bark is the fundamental concept of control in Schutzhund protection, and we teach it thoroughly before introducing any of the other skills.

How we teach the hold and bark is absolutely vital, because this exercise will constitute the dog’s first encounter with the issue of control. If the dog learns to channel its energy, to switch gears instantly from one behavior to another , carrying its drive intact , then it will gain the primary ability needed for championship‑level protection. If, on the other hand, we inhibit the animal in order to control it, then we will sacrifice something in it that we may never regain.

In drive work, we have already taught the dog that it must bark in order to bite and that its bark has the power to move the decoy, to animate him so that he becomes prey. However, during drive work the animal was always restrained from biting by the leather collar, and barking was inseparably coupled to lunging and fighting the leash. Our problem now is how to uncouple barking from lunging, so that the dog chooses to hold and bark instead of biting when there is no leather collar holding it back.

For this we need a third person. In bite work there is so much to be done all at once and so quickly that the handler needs an assistant who handles the lines for him. The assistant makes corrections, and does much of the physical work of restraining the animal, leaving the handler free to give commands and to praise and support his dog. From now on, when we refer to an assistant , we speak of someone who helps the handler by taking over some of the duties of controlling the dog.

Important Concepts for Meeting the Goal

1. Uncoupling barking from lunging

2. Correcting “dirty” bites

3. Keeping the dog “clean” when sending it from a distance

4. Keeping the dog “clean” when rounding the blind

5. Keeping the dog “clean” off leash

6. Proofing the hold and bark

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 970;