Proofing the hold and bark

The single most frequent complaint that we hear at Schutzhund trials is: “But my dog has never done that before!” And, invariably, it has never committed that particular error before. But it picked the day of competition to experiment for the first time with some utterly unexpected mistake, such as charging straight at the judge when commanded to “Search!” or some other appalling error.

These humbling occurrences are a reflection of the strange chemistry of the trial field. For, on trial day, something is different. Even though the exercises are the same–and the agitator, the blinds and even the field are often the same as in training–one thing is different: the handlers. We are so nervous that we are nauseated, with mouths so dry we can barely swallow. The animals reflect our anxiety in their behavior, and our seemingly stable, polished exercises disintegrate into vaudeville.

The effect is even worse when we “make the big time,” when we travel out of our region or even to another country for a major championship. Here, the helpers are new, the field is totally different, the blinds may be constructed entirely differently and our nerves are raw.

A German friend told us once about the experience of competing in the German National Schutzhund III Championship, the largest working‑dog event in the world. “You have no idea what it is like. You walk into the arena with your dog and there are twenty thousand people waiting to see you. Everyone is talking, cheering, so excited. You can cut the air with a knife! Your dog, it feels it, and it becomes so strong, crazy like you have never seen it. It won’t listen. All it does is bite!” (This is the good kind of problem to have in these circumstances. The other kind is when your dog becomes weak like you have never seen it, and refuses to bite at all.)

The process of overtraining the animal so that this does not occur is called proofing. Some trainers approach proofing by relying upon routine. They run the whole series of exercises, in order and according to all the rules, so many times that for both the handler and the dog all commands and responses become automatic, mechanized. The problem is that this requires much useless rehearsing of exercises that are already nearly flawless and will only suffer by repetition. The process is boring, and will soon take the luster of power and energy off the animal.

We proof in a different way, by perfecting the dog’s performance in bizarre situations that are far more demanding than the trial itself. We have no set progression of exercises. Instead, it is a matter of inspiration and improvisation. Here are some scenarios that we have used successfully for proofing the hold and bark:

• performing the exercise inside a building, or on a slick floor, in the near dark, or in the glare of headlights, among crowds of loud, jostling people, inside vans, or in the beds of pickup trucks, even on flights of stairs

• performing the hold and bark on seated agitators, costumed agitators or agitators equipped with bite suits or hidden sleeves instead of Schutzhund sleeves

• setting up foot races to the blind of thirty, forty or even seventy‑five yards. The helper is given enough of a head start so that he can reach the blind and freeze just before the dog arrives. If the animal can control the white‑hot desire produced by the pursuit–skidding into the blind, bouncing off the agitator without biting him and settling into a hold and bark–then there is little that will disturb its performance on trial day. (This procedure is also excellent for lending power to its bark in the blind, because it will make the dog very “pushy.”)

Our method of teaching the hold and bark produces dogs that are powerful and clean in the blind, not dogs that sit in front of the sleeve and yap politely for a bite, nor animals that bark helplessly from a distance. It produces animals that (for lack of another phrase) push in close to the agitator and “get in his face”–demanding that he move so that they can bite him.

GOAL 2: The dog will out cleanly on command.

Once the dog has a flawless hold and bark, the out is very simply taught. However, it must be well taught. If we school the out badly or incompletely, it will haunt us for the rest of the dog’s working career.

Early on in training, when the animal is still comparatively naive, we have one chance to teach it that it must release its bite on command–one opportunity to convince it that we are omnipotent and that we can reach it anywhere on the field and correct it if it disobeys. If we squander this opportunity, if the dog learns that we are actually far from omnipotent, then we will create a very persistent training problem for ourselves.

The amount of force used is critical. Too much force will inhibit the dog, killing drive and disturbing its mouth so that it bites badly or uses only a half mouth when it senses an out coming. Too little force will give the animal the opportunity to resist us, to fight the out, and as the frustrated handler gradually increases the severity of his corrections, the animal’s ability to endure them will increase as well. Soon the dog will bum as much energy fighting the out as it does fighting the decoy.

We differ from some other trainers in our desire to preserve, as much as possible, our dog’s sensitivity to us and to the correction collar. (Intensely hard animals are prized usually only by those who have never attempted to control one in bite work.) We preserve sensitivity by giving the dog little experience with corrections, so that it never has the opportunity to get used to them. When we correct, we do so sharply and effectively, so that there is not even a question of the dog resisting us. The animal quickly does as we ask and therefore undergoes few corrections. This has the effect of saving both dog and trainer a great deal of grief.

Important Concepts for Meeting the Goal

1. Back tying the dog

2. Forcing the out

3. Preventing discrimination

4. Outing the dog at distance

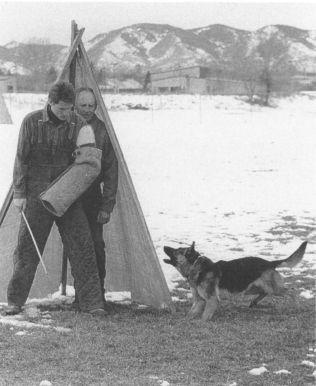

The handler hides in the blind behind the decoy, ready to step out and correct the dog should it bite instead of hold and bark.

Our method produces dogs that are aggressive and bold in the blind, dogs that move in close to the decoy and demand their bite. (Janet Birk’s “Jason,” Schutzhund III, FH, IPO III, UDT, WDX. We believe that Jason is the most titled Chesapeake Bay Retriever in the history of the breed.)

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 982;