Uncoupling barking from lunging

The assistant holds the dog on two leashes–one connected to an agitation collar, the other running to a correction collar.

As in all bite work up to this point, the dog is not under any obedience command and it is wild with excitement. The handler stands near and encourages the dog to bite the decoy, commanding “Get him!” The assistant restrains the animal with the wide leather agitation collar, letting the correction leash hang loose.

The exercise begins, as do all control exercises, with an excitation phase. Rather than soothe or calm the dog, we stimulate it. As if it were a turbine, we try to give the animal momentum by running it up as high as it will go. The helper therefore agitates the dog vigorously, moving in close to it and letting it try for the sleeve several times. After five or ten seconds of excitation, the agitator steps back a pace and “freezes.” An instant later, two things happen simultaneously.

• the handler commands his dog to “Search!”

• the assistant drops slack into the agitation collar leash and, before the dog can lunge forward and bite, checks it sharply with the correction collar

Each time the animal surges forward it is met with a jerk just strong enough to stop it. The assistant’s objective is to get the dog to stop lunging, stand back off the collar so that the leashes hang slack and bark. Furthermore, he must do this while inhibiting the dog as little as possible.

The dog is often very persistent about lunging and attempting to bite. As the animal fights the collar and the agitator stands still and the seconds tick by, the turbine winds down. As the animal calms, it gradually ceases lunging. Unfortunately, it often ceases barking as well, and only stares fixedly at the decoy.

It is the agitator’s job, when he sees this happening, to jump away (the dog loses its quarry when it does not bark!) and restimulate the dog. As he does so, two more events occur simultaneously:

• the handler exhorts the dog excitedly, commanding it again to “Get him!”

• the assistant snaps the slack out of the agitation collar leash, bringing it tight, and drops slack into the correction collar leash, so that the dog is free to lunge into the leather collar in pursuit of the helper

After five to ten more seconds of excitation, the decoy freezes again, the handler commands the restimulated dog to “Search!” and the assistant changes over once more to the correction collar.

The perceptive reader will see that there are two phases to the procedure: a drive phase , in which the dog is free to strive against the collar, to bite the agitator if it can; and a control phase, in which the dog cannot strive, and must restrain itself instead.

We cycle repeatedly from one to the other, using the drive phase to stimulate the animal and then dropping it unexpectedly into the control phase, where it has nothing to do with its energy but bark. The more suddenly we make this conversion, the more drive the dog will carry into the control phase and express by barking.

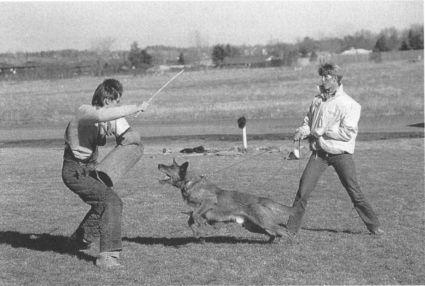

Above: The handler restrains the dog with the leather collar while the agitator stimulates the dog (drive phase).

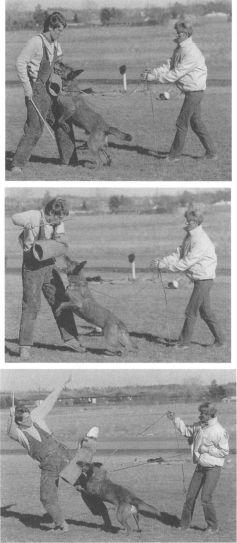

The agitator freezes, and the handler prevents the dog from biting with the correction collar (control phase).

At right: After several repetitions, the dog barks without attempting to bite, and…

…the agitator rewards it by moving (return to drive phase) and…

…then immediately slips the sleeve.

If, after two or three cycles, we are not successful in uncoupling barking from lunging at the agitator–so that the dog does not do the former without the latter, but simply wears itself down into panting silence instead–then the decoy runs away, agitating furiously, and hides. Loss of the opportunity to bite will frustrate the animal and make it more likely to hold and bark next time.

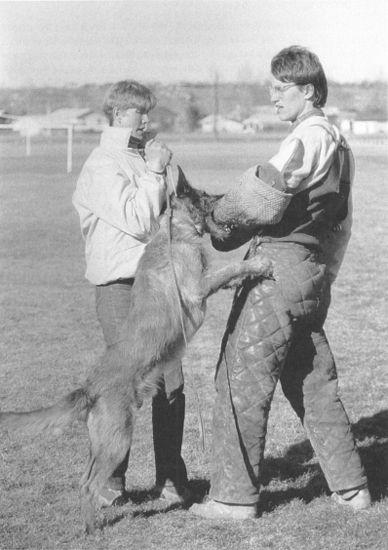

Eventually when, due to chance or to frustration and perplexity on the dog’s part, it finds the solution to the puzzle by rocking back off the collar and ripping out a bark or two, we reward it instantly. The agitator leaps backward, yelling, and the assistant drops the leashes so that the dog can surge forward and bite. The handler comes up and praises his dog extravagantly, patting and encouraging it while it bites.

Then, before the dog has enough of biting, the agitator slips the sleeve, the handler breaks the dog loose from it, the assistant takes up his lines and the cycle is quickly repeated while the memory of what it did to achieve gratification is still fresh in the dog’s mind.

With this system we present to the dog some basic rules that will hold true throughout training. We also present it with a problem and let it learn actively and powerfully by waiting until it stumbles onto the solution itself. The sequence goes like this:

if we physically hold you back…

if the decoy is in motion…

if we command you “Get him!”…

…then go for broke, strive, get him if you can!

However:

if we stop restraining you physically…

if the decoy is motionless…

if we command you “Search!”…

…then you are responsible for holding yourself back.

But what do you do with your energy?

Channel it to another behavior…

BARK!

…and you will be rewarded!

2. Correcting “dirty” bites

If the procedure is executed perfectly, the dog will never have the chance to take a dirty bite when the agitator is standing still. The animal will attain its goal and relieve its frustration only by channeling to barking and thereby winning the opportunity to bite. As a result, it will soon lock in to the hold and bark. This is the way that dogs become clean for life in the blind.

However, in dog training very little works perfectly, and when we least expect it, an aroused dog will steal six extra inches of slack from us and grab the sleeve. What do we do?

The traditional method is to punish, to take vengeance, to physically correct so severely that the animal never forgets the retribution and pain associated with a dirty bite. The problem is that this treatment will inhibit the low‑ to medium‑powerful dog, and it will enrage the very powerful dog, so that it bites twice as hard next time around.

There is another way. The object is not to take vengeance upon the animal when it makes a mistake; the object is to cheat it of its aim unless it does the job our way. What is the dog’s aim? Not just to bite, but to spend drive, to make combat. That takes two. In order for a bite to be gratifying, the decoy has to fight back.

Accordingly, if the dog takes a dirty bite, the decoy simply stands absolutely still. The handler steps up, tells the dog quietly “No!” and breaks it off the sleeve very quickly. The exercise is immediately repeated. There is no yelling, no emotion, no excitement. The error is “glossed over” as though it never happened. The excitement and emotion will come next time when the dog does a fine hold and bark. The decoy will give it a wonderful, vigorous fight for the sleeve, and the handler will exclaim his pleasure and praise of the dog.

3. Keeping the dog “clean” when sending it from a distance

Thus far, the dog has remained stationary and the decoy has come to it for the hold and bark. Now we are ready for the animal to advance and the agitator to stand still. We must be prudent because, when the dog takes a run at a person, it has not only physical momentum but psychological momentum as well, and is very likely to forget itself and bite.

Therefore, in the beginning, the assistant carefully walks the dog up to the decoy on the leather collar, and then checks the animal with the correction command if necessary. As the dog becomes more and more reliable, the assistant will move it faster and faster and over progressively longer distances in order to reach the agitator, until he is finally running as fast as he can in his efforts to keep up with the dog.

During this procedure, the handler should vary his position about the field, giving his commands from different distances and directions. If the dog is absolutely clean, so that it stops short and begins to bark all on its own with no correction or cue necessary, then we are ready for the next step.

When the dog takes a dirty bite, the agitator should stand absolutely still. The handler tells the dog sharply “No!,” steps up closely and breaks it quickly off the sleeve. The correction is made calmly and without anger, and then the exercise is immediately repeated.

We must now let the dog run free to the decoy–without the assistant at its heels. We keep the animal clean by sending it on a long line.

Beforehand, the assistant measures the line out on the ground and marks the spots where he will stand and where the decoy will stand. This way he knows just how much line he has to work with, and he can check the animal at exactly the right moment, if necessary. However, if its schooling is proceeding correctly, the dog is already much bound by habit, and the line should be almost superfluous.

If it is necessary to correct the animal again and again with the line, then the dog is not yet ready to progress to this stage of training.

4. Keeping the dog “clean” when rounding the blind

So far, we have performed all our work on the hold and bark in the open field. We have not yet tried the exercise in a blind. The blinds can present us with two difficulties:

• Some animals are a little shy of the blind, so that they are not quite as powerful when they are required to enter this more enclosed space in order to bark. This is normally easily remedied with just a bit of work in and around the blinds.

• In trial, the dog approaches the blind from behind. When it rounds the comer, it sometimes finds itself at a distance of less than two feet from a person that it has never seen before who is wearing a sleeve. The result of this sudden, almost startling encounter is often a dirty bite and the resulting penalty by the judge.

The solution is simple. Consider the blind to be the center of a clock face, with the opening directly at 12:00. On a long line, we send the dog for a series of holds and barks. The first is from 12:00, where the dog can clearly see the decoy. The next is from about 3:00, where the animal’s vision of the decoy is partially obscured. The next is from 4:00, where it cannot see the decoy at all, and so on. However, the assistant never moves farther than 3:00. He always remains where he can see the opening of the blind and what happens there when the dog arrives, so that he is ready to correct with the long line if the animal nips or bites.

In this way we can gradually accustom the dog to staying clean during an increasingly sudden encounter with the decoy when it rounds the blind.

5. Keeping the dog “clean” off leash

The issue is not completely settled yet, because the dog is by now very conscious of the role the nearby assistant (and the correction collar, and the long line hanging from it) plays in controlling it. We cannot be sure that the dog is absolutely clean rounding the blind until we can send it fifty or seventy‑five yards with nothing around its neck but a chain collar, and no one within 100 feet of the blind.

But this procedure could be very risky. If the animal bites, it will obtain a great deal of gratification before we can get to it and stop it. In addition, and far worse, the dog will learn something about the limitations of its trainers: when we can control it and when we cannot.

The first time that the animal runs free to a blind, we must be certain of two things: (1) that the dog is near certain to do just what we want it to, and (2) that, in the event it does not do so, we can surprise it with a totally unanticipated correction unrelated to the collar, long line or the assistant.

The solution is, again, simple, and one of the most elegant techniques that we have discovered in Schutzhund training, because it arises from such a sharp insight into what the dog can and cannot do with its mind.

The handler brings the dog onto the field wearing all the training paraphernalia–leather collar, correction collar and the long line–and then he makes a great show of removing all this equipment and throwing it aside, one piece at a time, as if to say to the dog, “Here, do what you want. Now I am helpless to stop you!”

The handler gives the dog, wearing only a chain collar, to the assistant. Suddenly the decoy appears and, from close range, begins to agitate the animal furiously, working it into a frenzy. Meanwhile, the handler sprints for the distant blind and hides in it. A moment later, the decoy follows him, still agitating, and piles into the blind on top of the handler, standing in front of him and hiding him from sight.

Because the dog is only a dog, and distinctly limited in terms of the kind of mental transformations it can make in space and time, it will always be surprised to find its handler in the blind with the decoy.

If the dog rounds the blind, beside itself with frustration, sees the agitator so temptingly close and bites, its handler will step out and grab it. The handler shouts “No!” while breaking the surprised animal off the sleeve and drags it back extremely brusquely, as though the dog were no more than a bag of cement, and gives it once more to the assistant. Note that there will be no abuse, anger or vengeance taken upon the dog. Then the exercise is immediately repeated.

About the time that we suspect that the dog has our stratagem figured out, we switch. This time the handler releases the dog, which, realizing that it is leaving its handler behind it in the open field, may be tempted to bite, only to find the assistant hiding in the blind and ready to correct it.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 956;