An Overview of the Protection Phase

The Protection phase of Schutzhund work has raised more eyebrows than any other aspect of the sport. Some people consider it cruel and savage. Others say that it is too dangerous. Still others believe that protection training somehow returns the dog to a wild state. Despite these misapprehensions and the criticism that arises from them, we consider protection to be the most exciting of the three phases of training. It is also at the core of the purpose of Schutzhund sport–to test, select and promote dogs of character and working ability.

These myths and misconceptions surrounding Schutzhund bite work still persist and must be refuted. One frequently voiced concern regarding protection is that the training will alter the dog’s temperament. However, experience has shown that a dog that is confident and friendly before protection training will remain confident and friendly after protection training. We do not brainwash the animal in any way. We merely strengthen and mold a perfectly natural facet of its behavior that we can already see in some form or degree in the dog before it is ever exposed to agitation.

Another myth surrounding Schutzhund bite work is that the training involves cruelty to the dog. Nothing could be further from the truth. After all, the primary objective in bite work is to build and maintain confidence, and this state of being cannot be evoked by cruelty or by force. Confidence and self‑assurance evolve instead as a result of a carefully designed series of exercises that teach the dog, first, to display aggression in appropriate circumstances and, second, that it can always expect success in so doing. The dog must develop the self‑assurance necessary to oppose a human willingly, with conviction and with force. This it will not do if abused or mishandled.

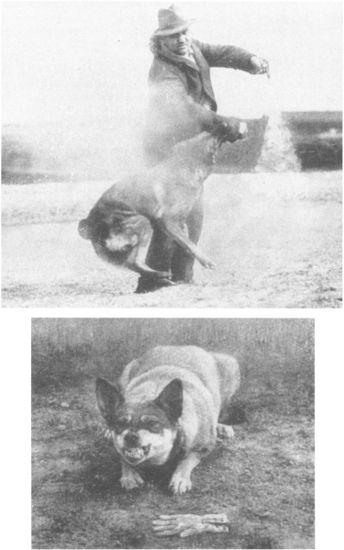

The protection phase of Schutzhund has raised more eyebrows and more controversy than any other aspect of the sport. (Stewart Hilliard and Chuck Cadillac’s “Gitte.”)

The use of the reed stick during Schutzhund protection routines caused much criticism and concern during the early years of Schutzhund in the United States. However, for a number of reasons, the stick hits are not dangerous for the dogs nor even particularly unpleasant. Stick hits are carefully and precisely administered by an agitator who is expert at his craft, and the blows fall to one side or the other of the dog’s spine, on the thick dorsal muscles of the back. Because the stick is very light and flexible, the dog is covered with fur and the agitator is skilled and experienced, no harm comes to the animal. Although the stick hits, characterized by sharp, menacing gestures, reflect a threat to the dog that it must withstand in order to pass a Schutzhund examination, they inflict at most a brief sting.

Indeed, the animal shows us clearly whether this pain is important to it, for it has the choice to undergo the stick hits or not. If the dog finds the blows truly unpleasant, if it is frightened by them, then it will bite badly or not at all while under the stick. Consequently, because it does its trainer no credit, the dog will be retired from Schutzhund and it will never see the stick again. If, on the other hand (like a football player who repeatedly endures far worse than a brief sting for his love of the game), the dog is so transported by the passion and excitement of bite work that it is oblivious of the blows, then we can unmistakably see that the dog has made its choice to go eagerly under the stick. We therefore admire the dog and use it for precisely this quality in it. The issue of the stick hits illustrates most clearly the central dynamic of Schutzhund sport: The Schutzhund dog loves the game.

A final misconception involves the common conviction held by many dog owners that their dogs will, without benefit of training or experience, protect them in a dangerous, real‑life situation. This is extremely unlikely. Most family dogs are systematically discouraged from behaving aggressively under any circumstances. In addition, the majority of dogs simply do not possess the necessary courage to bite when suddenly threatened. Their immediate and quite reasonable response is to retreat from an ominous situation with which they have not had any previous experience. The fact that a dog barks aggressively from behind the safety of a fence or a door is no indication that it will protect its owner when push comes to shove. Even in the case of a dog of unusual quality, a great deal of schooling is necessary to overcome the dog’s ultimate inhibition against biting and to develop its confidence and expertise in protection.

In fact, it is extraordinarily difficult to induce a dog to bite a human for real, and as trainers we spend an inordinate amount of time and energy striving to overcome this problem. Many dogs are willing to threaten, harass and even nip when they have someone on the run or when they confront a person who is not particularly dangerous. However, this is not the sort of person against whom we need protection. For a dog to enter into close combat with a person who is unafraid and genuinely means to hurt somebody is a different matter altogether.

Remember, biting is an extreme act. The animal in question must be either extremely frightened or extremely brave.

In an emergency, it is best if the dog is not only brave but also well trained, and a dog that has proven its courage and steadiness on the Schutzhund field and that is then schooled in personal protection can provide many years of service as a reliable family guardian.

Despite the advantages of owning and training a well‑schooled Schutzhund protection dog, there can also be decided disadvantages. Training a dog to a high level of competence in bite work is a long and arduous process. To begin training and then not follow through to this level of competence is to invite problems. A dog that is not fully trained has neither the control nor the judgment necessary to make a good decision, and a mistake of judgment with such a powerful animal can result in injury to an innocent party and a possible law suit.

In perfect truth, whether well trained or not, dogs simply do not possess the capacity to safely and reliably judge when and whom they should bite, and when not. Therefore, the responsibility for this judgment rests entirely in the hands of the owner. It is up to him to constantly and accurately predict his dog’s reactions in daily situations and to restrain the animal if there is a possibility that the animal will behave aggressively when in reality there is no danger.

For this reason, the person who is considering Schutzhund must be reflective regarding his own needs and competencies. His attitude toward the dog must be one of respect for a powerful weapon. The owner must have the determination and the ability to make good decisions regarding the safety of his dog and of other people.

It should be evident that, contrary to the lurid image bite work conjures up in the imaginations of the uninformed, training is carried out gradually and in a humane manner.

The process of building the dog’s confidence and developing its instincts is called agitation, and it is an art. The person who performs this work is called the decoy, the agitator or the helper , and his function is to serve as the dog’s adversary in order to progressively develop the animal’s desire to bite and to increase its courage. The agitator must be an athlete, physically strong and agile, but more importantly he must also be a person with what we call “feeling”–an accurate intuition for what makes dogs behave the way they do. The agitator must have the ability to observe a dog for a moment and then know what is in its heart. An expert agitator makes a good dog better. A mediocre agitator can make even a good dog look mediocre. A poor agitator can ruin a dog.

Throughout the protection section of this book we use the terms agitator , decoy and helper interchangeably. We prefer the term agitator because it best describes what the person actually does. However, we also use helper because this has become, for the sake of public relations, the officially accepted title (“help” has a more innocuous connotation than “agitate”). We include decoy because this term is commonly used on the training field in many parts of the country.

Early German service dog trials. Two exercises that no longer play a part in Schutzhund: the attack under gunfire (top) and guarding an object (bottom). (From von Stephanitz, The German Shepherd Dog, 1923.)

In addition to a competent handler and a gifted agitator, a Schutzhund team requires the right dog. The dog must have certain qualities of character. It is easy to imagine that the most aggressive, nasty, suspicious, hyperexcitable animal possible would be a good candidate, but this impression is totally incorrect. Rather than suspicious (a trait founded upon unsureness), the Schutzhund dog must be strong in character–steady, friendly, reliable and confident. The dog must be rational, in the sense that it must be capable of distinguishing between real threats and the normal, sometimes chaotic events that surround it. Thus, the single indispensable character trait of a working dog is stability. The animal must be steady, neither timid nor inappropriately aggressive. It may be friendly or it may not, but above all it must not be unreliable or dangerous.

The animal that snarls at a person approaching it, or tucks its tail and anxiously growls in a group of people, is not representative of the Schutzhund dog, both because it is not safe or reliable and also because it does not express the necessary power. It is from steadiness and neutrality–and the courage they bespeak–that the dog’s ultimate power in bite work arises. Contrary to common belief, the Schutzhund dog is not filled with suspicion or hate for the agitator. It does not bite from rage, fear or malevolence. It does it because the activity fulfills a great number of its instinctual needs. Quite simply, the Schutzhund dog bites because it likes biting.

The animal’s nature is that of a hunter, a predator, a fundamentally aggressive animal. Its urges to chase, bite and struggle are part and parcel of its life instincts. Just as it finds pleasure in eating and mating, so it also gains intense gratification from biting.

This point must be absolutely clear: We do not teach the Schutzhund dog to bite. Biting is not an artificial or contrived behavior, like wearing clothes or riding a bicycle are for a circus bear. As Schutzhund trainers we merely take a behavior that is already native to the dog and we channel it, strengthen it and mold it to suit our purposes. Therefore, it should be evident that we can only train the dog if it wants to bite. If it does not, then nothing remains but to find a new dog.

In Schutzhund protection the dog is a voluntary, even an intensely eager participant.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1363;