An Overview of the Tracking Phase

The use of scenting dogs in the service of humans has a long history. The ancient Greeks are known to have used dogs for tracking criminals and runaways, and the great Athenian playwright Sophocles even recorded the escapades of such dogs in his satire The Tracking Dogs.

In more recent times dogs have been used to search out the lost and injured on battlefields. In 1893, the German imperial army established an ambulance corps that used dogs trained to sweep an area looking for wounded soldiers. When the dog discovered a victim, it would find an article of clothing and return with it to its handler. The handler would then follow the dog back to the injured man. The dog sometimes had great difficulty in locating an appropriate article to take back to the handler, so eventually a device called a bringsel was introduced. The bringsel dragged from the animal’s collar on a short cord as it searched the battlefield. When it found a wounded man, it would take the bringsel in its mouth and retrieve it to its handler, signifying that it had discovered a casualty.

During World War I, in the mud and carnage and chaos of the trenches, ambulance dogs rendered great service to wounded soldiers of both German and Allied armies alike. The immortal Rin‑Tin‑Tin was reportedly a son of one of these ambulance dogs. Born under fire in the trenches of World War I (to a bitch said to have been captured from the Germans), he was taken home by a returning American soldier and finished his days in Hollywood as a film legend.

Later, during World War II and the Vietnam War, the United States Army made extensive use of the scenting powers of scout dogs in the Pacific islands and Indochina. These animals led patrols at night through the dense jungles, helping to locate enemy units and warning of ambushes.

For many years, search and rescue dogs have been used to find people lost in remote areas. More recently avalanche and disaster dogs have been trained to detect bodies buried under many feet of snow and debris. Search dogs have received international publicity in the last few years as a result of three enormous disasters. In the first, the eruption of Mount St. Helens in the Northwest, dogs went into the ash‑covered and barren quake area to locate bodies. After the Mexico City earthquake in the mid‑1980s, dog teams from around the world, including Schutzhund‑trained animals from Germany, were sent to find survivors and bodies trapped under crumbled offices, hospitals and apartment buildings. Most recently search dogs received headlines again when they searched out victims of the Armenian quake, which killed 20,000 people.

Modem military and police organizations worldwide use dogs trained in scent work to locate narcotics, weapons and bombs. In America, hundreds of law enforcement agencies employ police service dogs. Every night in cities and towns all over the United States criminals hoping to escape detection are found and apprehended through the scenting powers of police K‑9s.

Officer Jack Lennig of the Lakewood, Colorado, police department shared two of his favorite nose‑work stories with us: The first occurred one night while Officer Lennig was cruising his beat. He saw a young man in an alley who fled the moment he saw the police car, disappearing into the rabbit warren of alleys and lots behind a major red‑light district. On the assumption that anyone who ran like that had something to hide, Officer Lennig started his dog Beau on the man’s track. The animal led him perhaps a quarter of a mile through backyards and trash‑choked lots, and across a four‑lane highway. Finally, Beau turned a comer onto a major thoroughfare and followed the sidewalk a short distance to the door of a bar. Officer Lennig went inside and described the man to the bartender, who said that the fugitive had just been there and bought a drink, but left by the back door without finishing it. Officer Lennig started his dog again out back, and another quarter of a mile of alleys and asphalt parking lots later, the dog led him to the front door of a residence. The officer knocked at the door and the suspect answered it, protesting that he had been asleep in bed and hadn’t been out all night. Officer Lennig made a call on the radio, found that the man had several outstanding warrants and arrested him on the spot.

A more violent situation involved a woman walking home from work. A man jumped out of the bushes, dragged her to a nearby field and raped and robbed her, taking her diamond ring off her finger. Panicked by her screams, he pitched the ring into the field and ran off. The woman managed to flag down a Lakewood policeman and they returned with a K‑9 unit to the field. The dog tracked the suspect down, finding him hiding in his nearby home. Then the dog was cast out into the field to search for any additional evidence. Unbelievably, after a few minutes of intense searching, the dog returned to its handler and spat out the diamond ring that had been lodged deep in the grass of the field.

Officer Lennig has enough anecdotes of this sort to fill a book of his own. Like any experienced K‑9 officer, he is absolutely convinced of the value of a good scenting dog in law enforcement.

Officer Kenny Mathias of the Raleigh, North Carolina, police department, an authority on the subject, told us how a Dutch police tracking dog solved the famous Heineken kidnapping in Holland, in which a member of this wealthy beer‑brewing family was abducted. When the kidnapping vehicle was found, the police still had no suspect. So they laid a piece of gauze on the driver’s seat of the car, left it there for twenty‑four hours, and then sealed it in a jar. The gauze rested in the jar for two years while investigators developed a suspect. The Dutch police then performed a scent lineup, in which the suspect and four others impregnated sections of steel pipe with their scent, and the dog compared the scent of the gauze with that of the pipes. The dog matched the suspect’s pipe with the gauze and, confronted with the evidence, the man confessed to the kidnapping.

This anecdote amazes the authors and probably the reader as well. Two additional pieces of information are equally remarkable.

Glen Johnson, a well‑known expert on tracking, trained dogs to search out gas leaks on the Canadian pipeline. One of his dogs detected a wooden clothespin impregnated with gas odorant (used for training) that had lain buried underground for three weeks. The chemistry department of the University of Windsor, where Johnson teaches, estimated the odorant remaining on the clothespin at less than one part per trillion.

Search and rescue dogs are sometimes used on searches for victims of drowning. The animals are rowed back and forth across the water in small boats, and indicate their finds over the side. These dogs have discovered bodies in dozens of feet of water.

The inevitable question that arises is: How do the dogs do it? The authors have no idea how they do it, and we note with some amusement that the experts in olfaction do not know either. In fact, the physiological basis of scenting is simply not fully understood. Scientists are amazed at the diversity and the sensitivity of even the human nose.

Unlike taste, which is divisible into only four modalities (sweet, sour, salty, bitter), many thousands of different odors can be distinguished by people who are trained in this capacity. …The extreme sensitivity of olfaction is possibly as amazing as its diversity–at maximum sensitivity, only one odorant molecule is needed to excite an olfactory receptor. (Stuart Fox, Human Physiology, 2nd edition. Dubuque, Iowa: William Brown Publications, 1987.)

Fox makes these comments in relation only to the human nose. We can only guess at the rich experience of the world that a dog’s nose gives it, because a dog’s nose is so different from a human’s. A human being’s nose contains approximately five million olfactory receptor cells dispersed across about one square inch of area. In contrast, the average German Shepherd Dog possesses approximately 150 million olfactory receptor cells distributed in about six square inches of nasal epithelium (Pearsall and Verbruggen, 1982).

Not only is the nature of the dog’s “smell” experience different from ours, but it is behaviorally far more significant to it. In humans, primates who began eons ago as tree dwellers, the primary aims of behavior are accomplished visually. Primates use their eyes to locate food, avoid contact with predators and motivate sexual activity, whereas dogs rely to a great extent upon their noses for the same purposes. Yet a human can differentiate among some 4,000 different odors (Pearsall and Verbruggen, 1982). Only our observations of scent‑detection dogs give us any conception of the unimaginable abilities of a dog in this realm.

Since the exact physiological mechanism of olfaction is unknown, much of the process of tracking is still a mystery to us. We are not exactly certain what it is that the dog follows when it tracks a human. According to Pearsall and Verbruggen in Scent , a track is:

the imprint we leave whether traveling through a room, a field or over a road. The track is influenced by such variables as wind, temperature, humidity, rain, snow, terrain, grasses and trees. Our track also is affected by the immense variety of living creatures that share the world with us.

There appear to be two ways that a dog is able to follow a track. First, it can follow the body scent. This scent is the unique aroma that each person or animal emits. The components of this unique aroma in part include skin particles, perspiration, oils and gases and also, in animals, scent glands. This scent follows the individuals and is carried in the air currents around where they have walked. Noted obedience and tracking trainer Milo Pearsall describes scent as “slightly‑heavier‑than‑air gas, very easily blown about by the wind, yet sticking tenaciously in part to everything it touches.” Some of this odor settles in a corridor around the footsteps while another part remains airborne.

Because smoke particles are approximately equal in size to those particles shed by the human skin, some of the most interesting evidence we have about the dissipation of scent comes from watching the discharge of smoke bombs. Even on a calm day with minimal air movement, visible smoke takes on a life of its own. It attaches to bushes and rocks, springs upward along the sides of inclines or buildings and lingers in depressions and areas of long grass. When the ground is cool, smoke clings thickly to the earth. When the ground is heated by direct rays of the sun, the smoke expands, thins and dissipates upward.

The second type of scent is the track scent. This is the odor that a person, animal or object leaves behind after coming in contact with the earth’s surface. It appears that this contact with the ground changes the scent of the disturbed area in some way. Track scent dissipates very slowly in comparison with body and airborne scent.

Which kind of scent should the dog follow? That depends upon what sort of tracking you are doing.

The normal criterion for success in police scent work and search and rescue is simple: Does the dog find what we are looking for or not? In service dog work we are not concerned with style or appearance, only with efficiency and results. Therefore, tracking dogs that are used for police work and search and rescue are trained to trail –encouraged to use both air and track scent. They follow the track rather loosely and will freely cast about for body and airborne scent, exploiting it in order to draw nearer to their goal.

Schutzhund is a competition. In the tracking phase points are awarded, and there must be a winner. One dog must track better than the rest, and in Schutzhund this means more exactly, more precisely on top of the footsteps of the tracklayer. Because body scent is widely dispersed and blown easily about by the wind, a dog that searches for body scent will quickly take to quartering. It will zigzag back and forth, working the fringes of the scent path, much the way blind people feel their way down a hallway by touching first one wall and then the other. Air scenting therefore leads to very inexact tracking.

In addition, air scent appears to be transient. Depending upon conditions and terrain, some fifteen to forty‑five minutes after the tracklayer has passed, his body scent has lifted and become so dispersed or discontinuous that a dog cannot easily follow it. Because the track scent lasts far longer and because it is much less affected by wind conditions than body scent, it is therefore more reliable and much more closely associated with the actual track itself. This is the scent we must teach the Schutzhund dog to follow.

An exquisitely trained competition dog actually footstep tracks in good conditions. This animal follows the track as if it were on rails, making geometrically precise turns, its head weaving from side to side across a six‑inch area as the dog locates and checks each of the tracklayer’s footsteps.

Because of the importance of track scent, the type of terrain and vegetation strongly affects how the dog will track. Hot sand, frozen ground, asphalt and stone are all difficult and nearly impossible for the dog to follow a track across. However, the veteran tracking dog eventually must be able to adapt to virtually any type of terrain and all weather conditions.

For teaching Schutzhund tracking, tracks on short, pastem‑length grass or soft dirt are the most suitable, as they retain the scent well. Tall grass retains odor all along its blades and the dog therefore tends to practice tracking with a high nose. Tall grass also shelters body scent from the wind and sun, so it dissipates slowly. When in an area of knee‑high grass, the tracklayer’s body scent will remain for a surprisingly long time dispersed in a wide area about the track. The resulting low‑hanging cloud of air scent among the grass stems will greatly confuse the novice tracking dog. Thus it is a good idea to avoid this type of vegetation during training sessions.

Hills can also have a pronounced effect on the dog’s performance because of the gentle uphill and downhill air currents that distract the animal from the track scent.

By causing the scent to drift, wind also affects the dog on the track. For example, if the animal is tracking into the wind toward a turn, it will tend to make its move before the actual turn. When the wind is at its back, the dog will turn slightly past the turn. Because of these and other factors we spend much time encouraging the competitive tracking dog to utilize primarily the track scent.

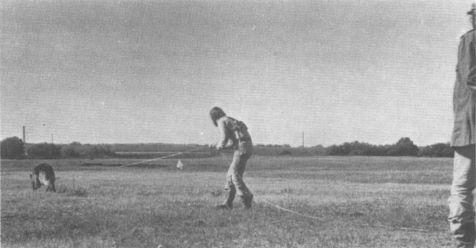

Trial day for Phil Hoelcher and his Kazan v. Anger, Schutzhund III.

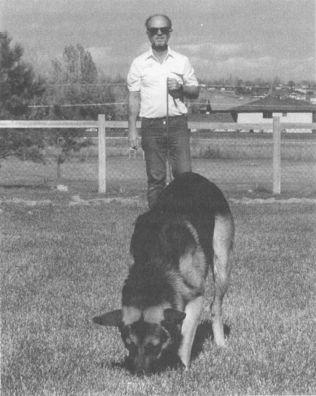

Dick Gasaway’s puppy “Zeus v. haus Barwig” demonstrates the two most important prerequisites for competitive Schutzhund tracking: concentration and a deep nose.

The age of the track affects the dog’s performance as well. On a fresh track where there is a great deal of body scent, many dogs do extremely well. (We conjecture that police dogs are often highly effective in following fresh tracks because of the intense aroma emitted by a frightened fugitive.)

Under normal weather conditions the track scent and body scent are approximately equal in intensity at about thirty minutes of age. After that time, however, the track scent begins to dominate.

The amount of time the track retains body and airborne scent varies with the weather and terrain. Any extremes in these conditions can cut down on the tracking dog’s effectiveness, but none of them need totally defeat its ability to perform.

Contrary to popular lore, the shape of the dog’s head has little effect upon its ability to track. Bloodhounds, for example, do not excel in tracking and tailing because of any special anatomical equipment they possess, and theoretically a Boxer has as much absolute ability to detect scent as a German Shepherd. The difference between an outstanding tracking dog and a mediocre one is not physical but behavioral–an innately greater desire to track and a gift for concentrating single‑mindedly upon a task for long periods of time.

Therefore, the most critical aspect in the success of a particular dog in tracking appears to be its motivation to track at the time its handler desires. Apathy, lack of concentration and refusal to work are all usually indications of incentive problems rather than an inability to perform. While we cannot easily change the style of a dog’s tracking, we can increase its incentive to do it. A slow tracker can become a slow, methodical worker. An overexuberant tracker can become a controlled, eager worker.

Basically there are three ways of motivating the dog to begin tracking. The most traditional method makes use of what old‑time German trainers called the dog’s pack drive –the animal’s desire to be with its master. Because of this desire, when its handler is hidden the dog will actively search him out. Von Stephanitz, and more recently Davis, as well as many police dog trainers have used this approach to training. With a highly motivated dog that has a natural talent for tracking, this method can be highly effective.

For a dog possessing less natural incentive, food often proves helpful. Some Germans do their training with a smelly piece of meat dragged behind the tracklayer to encourage the dog to put its nose to the ground and track. Glen Johnson, a well‑known Canadian authority on tracking, uses a food‑drop approach to begin all the dogs he trains. He uses the food drops to increase the dog’s motivation to track and to provide a reward for it when it is correct–when the dog is right on top of the track. It is also an excellent way to teach the dog to take scent in each footstep. However, the food drops are not intended to be continued indefinitely. They are eventually phased out.

We use a third type of motivator with a dog that is a natural retriever. In this dog’s training program its reward for tracking is finding an article or toy at the end of its track.

A fourth type of incentive is used infrequently. It involves motivating the animal by allowing it to find and bite an agitator at the end of the track. This bite‑motivation method is only effective with a small percentage of dogs. The most instructive reason for its effectiveness is the phenomenon of too much motivation.

The Yerkes‑Dodson law of psychology states that the most effective level of motivation for a task will depend upon the difficulty of that task. As expected, animals or people engaged in simple tasks profit by very high motivation. However, the performance of animals engaged in complex or difficult tasks is actually disrupted by very high motivation.

Because tracking is a very complex task depending upon concentration, and because bite work produces intense motivation, we should not be surprised that bite motivation usually disrupts performance in tracking.

The question of bite motivation illustrates an important point. The best tracking dogs are calm and methodical while they work. Not only is this the style that produces the most reliable, precise tracking, but also it is the style that will most favorably impress the judge. The emphasis in much of tracking training is therefore to slow the animal down and get it to concentrate, and the trick is to motivate it well but not too well. The Yerkes‑Dodson phenomenon also helps explain why attempts to train dogs for tracking by forcing them are so often ineffective, because fear can be thought of as the most intense motivator of all.

However, all the abovementioned training styles can and do work. The important thing is to select the right incentive for the particular dog.

The now classic method for training competitive tracking dogs combines two of these incentives–retrieving and food. Most Schutzhund trainers use a more or less modified Glen Johnson food‑drop approach to teach the animal to make use of track scent. In addition, they invariably associate the end of the track with a ball or some other retrieving toy such as a kong (an irregularly shaped and erratically bouncing dog toy), either by leaving the ball at the end of the track where the dog can find it or by simply pulling it out of a pocket when the animal has finished its task.

It should be clear that the dog has little innate motivation to arbitrarily follow any trail of disturbed ground. It does, however, have powerful innate desires for food and for the ball. The central concept the dog must learn in tracking is that the seemingly unrelated odor of track scent will guide it from one food drop to another, and ultimately to the ball, and win for it its master’s praise.

It is fascinating to note that von Stephanitz, in the early 1900s, had already realized that bite work should seldom be joined with tracking. In many ways this man was a visionary, and he espoused a training philosophy that is still adhered to today. He was a strong advocate of starting a dog in tracking work when young in order to “form and sharpen its mind through nasal experiences.” He insisted upon the use of a leash in training as a way to correct the dog’s faults and to teach it correctly. And it was he who suggested starting the dog’s schooling on its handler’s track and then switching to strangers’ tracks. As a final suggestion he stated:

In the development of the use of the nose, care must always be taken that everything is done in love and kindness, without any perceptible constraint. The track dog itself must, however, be trained very carefully and must be continually worked, for it is an artist, and an artist can only retain prominence when practicing and continually trying to improve on past efforts.

Many of von Stephanitz’s ideas have formed the basis for modern training practices. However, beyond his broad generalities there has been relatively little literature written on the art of training the tracking dog. One useful book on the subject is Glen Johnson’s Tracking Dog: Theory and Methods. It must be noted that the method presented in his book is geared to passing an AKC or CKC tracking test (TD), rather than to teaching the animal to use its nose in actual police or search and rescue situations. However, Johnson’s progression is systematic and discussed in a thoughtful, easy‑to‑follow format and can be adapted for Schutzhund tracking.

Tracking plays a critical part in the success or failure of the dog in a Schutzhund trial. As in the other two phases of sport, obedience and protection, a failure in tracking (less than seventy points) means no Schutzhund title. However, proportionately more dog‑handler teams fail the tracking test than any other phase.

Frankly, tracking can be baffling. In addition to good methods, the trainer also needs a feel for tracking. In addition to feeling, he needs a little luck. As if it were some arcane act, or a kind of black magic, some people seem to have the touch and some do not.

The uncertainty of tracking breeds superstition, and sometimes unusual behavior. At the trial, handlers often wear lucky jackets, boots or gloves, or use lucky tracking lines without which they would not dare to compete. They engage in rituals, arranging their lines just so, or preparing their dogs just so, as if to appease some capricious and ill‑tempered god who reigns over the tracking field.

The difficulty of tracking is that the animal must work on its own. The handler can give his dog only a minimal amount of help during a tracking test–particularly in Schutzhund II and III–and he is forced to rely entirely on the animal’s desire as well as its ability.

Tracking therefore requires a great deal of good, consistent training time; if good scores are desired in competition one must spend a disproportionate amount of this time initially in the basic teaching phase of tracking. We know that almost any dog can track regardless of even extreme adversity. Whether or not it actually does is a function of the training it has received and its motivation to do so. It is the handler’s responsibility to give the dog a series of tracks it can learn on as well as the incentive to learn.

The degree of similarity between an AKC tracking test and a Schutzhund tracking test is high. A dog ready to compete for its Schutzhund III degree is also ready for its TD. Both require that the dog track a stranger approximately 800 paces through a few turns. The advanced Schutzhund tracking test, the FH, is approximately equal in difficulty to a TDX. Both tracks are very long and well aged, and laid on difficult terrain with obstacles.

Whether training a dog for an AKC title, a CKC title or a Schutzhund degree (or schooling a tracking dog for actual service work) similar training techniques are required. Each desired behavior on the part of the dog must be scrutinized in detail. Each small part of the task must be taught to the dog until the animal has mastered it. Just as we would not expect a young child to know how to read a book simply upon being given one, neither would we expect a dog to know how to track because we have taken it to a scent pad and told it “Track!” It is not that the untrained dog does not yet possess the ability to detect and differentiate scents–in truth its skills are phenomenal in this area. However, this animal does not yet know what it is that we expect it to do with a scent. It is here we begin our instruction.

In some respects human beings and dogs learn tasks similarly. Both need to have what is taught them broken down into small increments. In this book, remember, we have organized Schutzhund exercises into increments for the reader and called them “Goals” and “Important Concepts for Meeting the Goals.” Just as in the obedience and protection sections, we have built them into the tracking section, breaking each skill required for the Schutzhund tracking test down into a series of goals and concepts. Each concept requires much practice. Each must be fully mastered before moving on to the next, and for each concept that the dog is in the process of learning, the animal will need success and reinforcement.

Just like the other two phases of a Schutzhund trial, tracking is not just a competitive training event but also an examination of character. On the day of the trial, before it is allowed to track, each dog is examined by the judge for its nervous stability. The animal must be steady, neither timid nor inappropriately aggressive. It may be friendly or it may not, but above all it must not be unreliable or dangerous.

Every judge, it seems, has a different way of examining the dogs. Some touch the animals, some just observe the dog’s behavior in the midst of a group of people. If any dog entered in a trial shows a sign of a severe flaw in temperament, it will not have the chance to track. Instead, it will be eliminated from the trial on the spot.

In addition, completely apart from the temperament test, by watching the dog on the tracking field an astute judge can evaluate the dog’s nerves and its bond with its handler, as well as its desire to work independently. He can gauge the animal’s confidence in itself and its work, its ability to concentrate and, very importantly, its drive to perform the task. It is during the tracking phase that the judge forms an initial opinion about the quality of the dog as well as the value of the training it has been given by its handler.

The following list contains some general considerations in training the tracking dog.

1. A large number of practice sessions should be provided for each concept, and each of these concepts must be mastered before proceeding to the next.

2. Beginning tracks should run into the wind so that the smell of the track will blow directly to the dog. Avoid cross winds on beginning tracks.

3. Beginning tracks should be laid on flat surfaces away from large objects in order to keep the scent and thus the dog’s nose in the footsteps.

4. Only when the dog is confident on the track and really understands the concepts of tracking should the wind, terrain and other environmental conditions be made adverse to its performance.

5. Tracking sessions should be kept positive. Avoid reprimanding the dog and using harsh obedience commands while preparing or running the track. This does not mean that the dog should never be corrected, but that a command such as “No!” should be said in such a way that the animal understands without feeling intensely pressured.

6. The dog should always find an article or reward at the end of the track. Even if the animal overruns or misses the original one, a substitute can be pulled from the handler’s pocket and thrown onto the track. The dog must always be successful.

7. Once the dog has passed its Schutzhund I, occasionally use a variety of tracklayers, both male and female, as well as tracklayers of varying weights. They should be encouraged to wear an assortment of foot‑gear. Of course, it is still possible and even advantageous for the handler to hone the dog’s skills by laying his own tracks, even at an advanced level.

8. If using a harness, it should be used only for tracking. Put it on the dog a few feet before the tracking stake and remove it immediately at the conclusion of the track so that the animal associates the harness with its work.

9. During the teaching phase it is necessary to help the dog find the track whenever necessary. Therefore it is absolutely crucial to know the exact location of the track. This can be accomplished by marking the track with flags, mapping it or learning the knack for remembering exactly where one has walked.

10. Only one variable should be manipulated at each tracking training session. For example, if we are changing the age of the track, we must keep the distance, type of terrain and wind conditions constant.

11. One should attempt a tracking session only when in a pleasant mood. Do not go tracking in an irritable, agitated or angry mood, and if things suddenly go wrong during training, put the dog in the car and go home, even if a track is already laid.

12. In order to give the dog additional encouragement, a time for play with the ball or a run in the field should always follow a tracking training session.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1399;