Outing the dog at distance

The training we have accomplished up to this point will suffice for all but very difficult dogs in the front work , the protection exercises in which the handler is relatively close to his dog for the out. However, for two reasons, the longdistance courage test outs will present problems with even an extensively overtrained and proofed dog:

1. These outs come immediately after the courage test. The dog is inspired and highly stimulated.

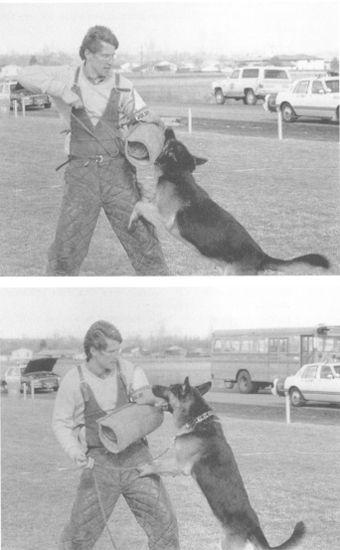

In order the enforce the out at a great distance from the handler, the decoy uses a short leash attached to the dog’s pinch collar and corrects the animal under the sleeve.

2. During the courage test, nobody is within 100 to 200 feet of the animal, except the decoy. The unfamiliarity of the context, in addition to the dog’s high level of spirit, can lead to disobedience and then discrimination.

In order to overcome these difficulties, we need a method of correcting the dog that

• does not depend upon the proximity to the dog of the handler or an assistant

• does not depend upon a cumbersome long line

• will not teach the dog respect or fear for the decoy or for the stick

The best method we have found makes use of a tight pinch collar and a short (two to three foot), very light line hanging from it. The dog drags the line with it as it goes down the field after the agitator (it has no wrist loop or knot to tangle in the animal’s legs) and after the bite the helper grabs hold of it under the sleeve with his free hand. If necessary for the out, he then corrects the dog with a short, precise movement of his arm.

The agitators who are good at this technique can deliver a relatively strong correction without making it obvious to the dog from whence the compulsion comes. It is important that the decoy does not command the dog himself or threaten the animal. He acts only as a mechanical agent for the handler.

Because of limitations on leverage, and because of the physical strength of even a medium‑sized dog, this technique will not work with a dog that is experienced in disobedience and determined to keep its bite. However, in the case of a well‑prepared and extensively overtrained animal that is inclined to out anyway, the method is ideal.

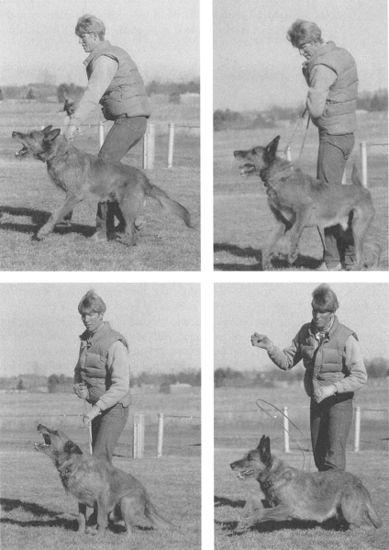

The handler restrains the dog physically while the agitator stimulates it from a distance of twenty or thirty feet (drive phase).

Then the handler quickly releases the dog’s collar, commands the dog to “Sit” and simultaneously corrects the animal into a sit with the leash (control phase).

After several repetitions, and in spite of being excited, the dog sits on command and holds its place without a correction.

The handler then sends the dog to bite with the command “Get him” (return to drive phase).

Protection: Obedience for Bites and the Blind Search

The three most important skills that the dog must master for Schutzhund protection are the hold and bark, the out and the blind search. However, there is in addition a somewhat bewildering array of minor skills that the animal must also master in order to turn in a polished performance:

• Schutzhund I attack on handler

• front transport and Schutzhund II and III attack on handler

• side transport (or side escort)

• down and search

• recall to heel from the blind

This list does not include a last aspect of the protection routine which is not one of the formal exercises but which plays a vital role in all of them. We speak, of course, of heeling–the not so simple business of moving a very excited and aggressive animal around the field with nothing but voice to control it.

Many trainers consume a great deal of their time and their dog’s energy hammering in each of these minor skills as separate and distinct exercises. Yet, interestingly enough, the minor skills are often the weakest points in otherwise excellent trial performances. It is quite common to see dogs in competition that are faultless in the hold and bark and the out, and yet are still very difficult to manage on the protection field.

As a result of many years of work with biting dogs, we have developed a system that overcomes this problem by uniting all the minor skills. Once the dog has mastered a single concept, which we call obedience for bites , the attacks on handler, the escort, the transport, the down and search, the recall and heeling all fall naturally and even effortlessly into place.

Of course, at this stage in the dog’s career, there is no need to teach it obedience. It already understands most or all the skills required. But understanding something is different than actually doing it. We must take into account the emotional and physiological context of training.

Certainly when the dog is in the mildly stimulated mood that prevails on the obedience field, it “knows” obedience and responds easily to commands. However, in the supercharged atmosphere of the protection field, obedience is another question entirely. During agitation, the dog is intensely aroused. This excitement is not only a function of its mood, but also it is a physiological phenomenon–a chemical event taking place within the animal’s body. Because its bloodstream is flooded with endorphins and other hormones that considerably alter its behavior and basic characteristics, it may seem a different dog when on the protection field.

Trainers who come to Schutzhund from competitive obedience are often taken unaware by the changes that come with arousal. Because they are unaccustomed to training animals in this excited frame of mind, they do not understand that bite work is a totally different realm of behavior than obedience and that consequently different rules apply.

For example, sometimes dogs that are otherwise as sensitive and gentle as lambs become so stimulated during agitation that they turn as hard as stone, and they will endure without a blink a correction that would normally devastate them. This transformation is a normal part of bite work, and takes place to some extent in every dog. It is also very much to our advantage, because in agitation we deliberately exploit arousal in order to develop power in the dog, the kind of power that will enable it to withstand all opposition from the decoy. Unfortunately, the same power can give the dog the ability to withstand its handler’s attempts to control it as well.

Arousal not only can make a dog harder than normal, it can also profoundly change its basic reactions to stimuli. For instance, sometimes physical punishment escalates an already intensely stimulated dog instead of settling it down. All the handler’s efforts to control the animal only arouse it further.

What all these remarks mean to say is that obedience on the protection field is a special case. Just because the dog knows what “Heel!” means does not ensure that it will actually do it when anywhere near an agitator.

The traditional remedy for disobedience is simply to punish the animal until it does as it is told, decoy or no decoy. In the process the handler finds himself continually battling with his dog, going head‑to‑head against all the power that breeding and training have given the animal. For the handler this is a no win scenario. If the dog wins the battle, the handler loses because he cannot control his animal. If the dog is vanquished and forced to obey, the handler loses anyway–because in hammering the dog into submission he has wasted a great deal of time and energy, and probably killed some of his dog’s character as well.

There is another way. By teaching the dog the obedience for bites concept, we can save its strength for fighting the decoy, instead of the handler.

Just like our methods for training the hold and bark and the out, obedience for bites is based upon the concept of channeling –diverting the animal’s energy smoothly from one behavior to another while inhibiting it as little as possible. Quite simply, we teach the dog to “buy” bites with obedience skills. We make no attempt to force the exercises. Instead, we present the animal with a clear proposition: Do it, or you don’t get a bite.

GOAL 1: The dog will remain focused on the handler and responsive to commands on the protection field.

Important Concepts for Meeting the Goal

1. “Coiling” the dog

2. Teaching attention with heeling

3. Teaching the minor skills of protection

1. “Coiling” the dog

Up until now, we have never asked the dog to obey any obedience commands during bite work. Except during the very brief periods when we dropped the animal into the control phase for a hold and bark or an out, the dog has spent all its time on the protection field in the drive phase. The dog burned energy at a stupendous rate, barking furiously at the agitator and straining into the leather collar that restrained it. For the dog, agitation has come to mean not just biting, but also the opportunity to strive, to spend itself, to vent the drive that fills it to bursting.

During training for the hold and bark and the out, we stopped the dog from striving into the collar for a few seconds at a time, taught it to channel its energy and express it by barking. Now, in obedience for bites, we will teach it to suppress its energy instead and hold it in check for gradually longer periods of time, coiling it up inside as though it were a great spring.

We cannot accomplish this by force, because the sort of harsh physical punishment that would be necessary to control the animal does not store its drive, but rather kills it. Instead, we do it by frustrating the dog, winding it tighter and tighter, and only letting it unwind when it does precisely as we ask.

The handler stands on the field with his dog at his left side, using his left hand to hold the animal back with the leather agitation collar. The dog also wears a correction collar, and the handler grips the correction leash in his right hand. We are in the drive phase.

The decoy begins agitating the dog, and the handler encourages the animal to “Get him! Get him!” The dog lunges and barks, striving against the collar. Then, suddenly, the agitator freezes, and the handler releases his dog’s leather collar and at the same time tells the dog to “Sit!” Now we are in the control phase. But the animal is, of course, far too excited to sit, and the handler will be obliged to correct it sharply into position.

Because a sit that we have to correct the dog into is no sit at all for our purposes, we repeat the exercise. The handler seizes the dog’s leather collar with his left hand and commands “Get him!” The decoy stimulates the dog for five or ten seconds, freezes, and then the handler commands his dog to “Sit!”

When, after a number of repetitions of the procedure, the dog drops into a tight, coiled sit instantly upon command and without a correction the handler rewards it. With a quick, excited “Get him!” he drops the correction leash and sends the animal to bite the agitator.

The emphasis here is not upon brutally overcoming the dog’s excitement. The leash corrections are only strong enough to sit the animal, not punish it severely. The emphasis is upon persistently denying the dog gratification until it solves the puzzle and realizes what it is that we want. Rather than controlling the animal with severe force, we rely instead upon anticipation. After several repetitions, the dog knows that another is coming and its anticipation of both the “Sit!” and the correction makes it ever more likely to obey the command. When, finally, it sits automatically and is then instantly rewarded, it begins to learn to fulfill its desire by carrying its energy into another behavior, and restraining it briefly so that the handler will allow it to bite.

After a few sessions on this kind of drill, the animal will learn to readily channel its energy into sits and downs and other obedience exercises in order to win its bite.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-08; просмотров: 828;