Preventing discrimination

Discrimination is the phenomenon that takes place when the dog realizes the limitations on our ability to control it. The following scenario will serve as an example.

The out is begun with a dog and taken to the level of 60 percent reliability, meaning that the animal outs cleanly and without a correction three times out of five but requires a reminder in the form of a crack on the collar the other two times. Amazing as it seems, this is often the point at which the typical trainer takes his dog off the back tie (or whatever other device he has used for corrections) “just to see what it will do.” (In dog training, anything done “to see what it will do” is premature, and therefore normally a big mistake.)

The dog’s behavior is still plastic, variable. The out has not yet become an inviolable habit for it. The result is that, because of the different circumstances that surround the exercise when the dog is not back tied, it disobeys. The indignant handler runs in from wherever he was watching and wrestles the animal off the sleeve, but in the mean‑time the dog has had the opportunity to bite for a while. And it has learned something. The rule that was in force–“out, or be corrected instantly”–is no longer in force when it is not tied up. The dog learns that the relationship between disobedience on the out and punishment changes according to the circumstances. It forms a new strategy to deal with the situation: “Regardless of any commands, keep biting until my handler gets near me.”

TRAINING FOR THE OUT

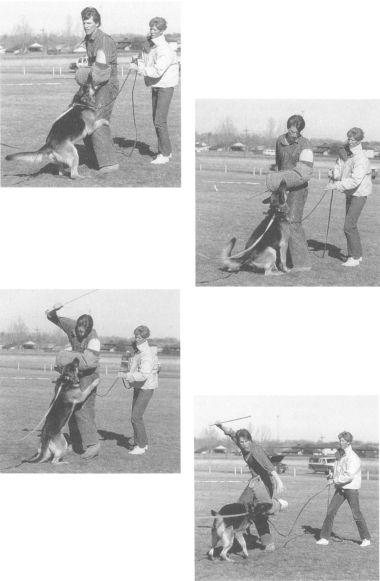

Above: The decoy brings the dog into the spirit by agitating it vigorously.

He allows the animal to bite the sleeve and fights it strongly for a few seconds.

At right: The decoy then freezes, the assistant makes ready to deliver a correction, if necessary, and the handler commands the dog to “Out.”

The dog releases the sleeve and begins to hold and bark.

After one or two barks, the decoy gives the dog another bite and…

…immediately gives the sleeve to the animal.

Outraged, the handler takes the dog back to the post in order to show it “what for.” He trains the out on the back tie for one or two sessions and then he again takes the dog off the post too soon. And again the dog refuses to let go when commanded to “Out!” It steals some gratification, and winds up back on the post.

Returning the animal repeatedly to the back tie, far from correcting the problem, actually makes it worse. Each time it goes through the cycle, the dog learns more about the limitations on its handler’s ability to control it. It makes the crystal‑clear discrimination that it must never disobey when tied to the post, but that it can disobey in other situations, depending upon certain factors like how close to it its handler is when the command comes, whether it feels the weight of the correction collar on its neck, where the assistant is, even whether it is trial day.

This scenario shows how a true problem dog is made. Here are some common “solutions,” and the additional problems that result.

1. The decoy corrects the animal by striking it on the foreleg with the stick.

The new problem: Stick corrections weaken the dog, teaching it respect for the decoy and fear of the stick. The last thing we want is for our dog to respect the decoy or fear the stick.

2. The handler stands near the dog and corrects it if it disobeys.

The same old problem: The correction is still dependent upon the proximity of the handler. What will we do for an out at distance?

The new problem: More seriously, this technique teaches fear and mistrust of the handler, so that the animal bites badly any time its handler is near. This, of course, is exactly the wrong state of affairs. The dog should draw strength and encouragement from its handler during bite work.

3. An electric collar is used to correct the dog on the out.

The same old problem: Discrimination is still possible; the animal can still learn when it is wearing the “live” collar and when not, especially if the methods used are slipshod (as they often are when a handler buys an electric collar as a cure‑all for failures in technique).

The new problem: The electric collar is a tremendously powerful (usually too powerful) compulsive training device, and must be used with great skill and flawless technique. Unfortunately, skill and technique in the use of the electric collar must be learned at the expense of a dog or two. Therefore, few trainers really know how to use this device. In addition, because of the particular nature of electrical stimulation, the electric collar has a tendency to weaken all but very hard animals.

The fundamental reality is that we lack the ability to control the animal at all times on the field and, ultimately, we depend upon nothing more than force of habit and our strength of personality to impose our will upon it.

The solution to this fundamental problem is to keep the dog from finding us out, to prevent discrimination. We do so by, first, avoiding the mistakes described above and, second, by overtraining the animal. We leave it on the post so long, and perform the out in so many different ways that it is virtually locked in habit. Its behavior where the out is concerned is no longer plastic. The dog outs invariably, no matter what the context. Discrimination is prevented because, since the dog does not disobey, it never learns that sometimes we are unable to control it when it disobeys. We are, as far as it is concerned, omnipotent.

We overtrain by proofing:

1. We perform outs under very difficult, distracting or stimulating circumstances that far exceed the difficulties of a Schutzhund trial. For example:

• out the dog off a decoy who is not frozen but actively struggling against the animal

• out the dog off a decoy who sits in a chair or lies upon the ground

• back tie the dog in a dark building, on a slick floor or inside a confined space and train the out

• practice the out while the dog is surrounded by a crowd of milling spectators

2. We make the dog practice the skill perfectly many times in order to establish it as an invariable habit. Remember, practice does not make perfect; perfect practice makes perfect.

Once the animal outs flawlessly in every conceivable circumstance, no matter what the difficulty, and has done so for several weeks, during which the correction line has lain slack and unused in the assistant’s hands, then it is ready to be taken off the back tie, and not before.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-08; просмотров: 753;