Proofing the hold and bark

The single most frequent complaint that we hear at Schutzhund trials is: “But my dog has never done that before!” And, invariably, it has never committed that particular error before. But it picked the day of competition to experiment for the first time with some utterly unexpected mistake, such as charging straight at the judge when commanded to “Search!” or some other appalling error.

These humbling occurrences are a reflection of the strange chemistry of the trial field. For, on trial day, something is different. Even though the exercises are the same–and the agitator, the blinds and even the field are often the same as in training–one thing is different: the handlers. We are so nervous that we are nauseated, with mouths so dry we can barely swallow. The animals reflect our anxiety in their behavior, and our seemingly stable, polished exercises disintegrate into vaudeville.

The effect is even worse when we “make the big time,” when we travel out of our region or even to another country for a major championship. Here, the helpers are new, the field is totally different, the blinds may be constructed entirely differently and our nerves are raw.

A German friend told us once about the experience of competing in the German National Schutzhund III Championship, the largest working‑dog event in the world. “You have no idea what it is like. You walk into the arena with your dog and there are twenty thousand people waiting to see you. Everyone is talking, cheering, so excited. You can cut the air with a knife! Your dog, it feels it, and it becomes so strong, crazy like you have never seen it. It won’t listen. All it does is bite!” (This is the good kind of problem to have in these circumstances. The other kind is when your dog becomes weak like you have never seen it, and refuses to bite at all.)

The process of overtraining the animal so that this does not occur is called proofing. Some trainers approach proofing by relying upon routine. They run the whole series of exercises, in order and according to all the rules, so many times that for both the handler and the dog all commands and responses become automatic, mechanized. The problem is that this requires much useless rehearsing of exercises that are already nearly flawless and will only suffer by repetition. The process is boring, and will soon take the luster of power and energy off the animal.

We proof in a different way, by perfecting the dog’s performance in bizarre situations that are far more demanding than the trial itself. We have no set progression of exercises. Instead, it is a matter of inspiration and improvisation. Here are some scenarios that we have used successfully for proofing the hold and bark:

• performing the exercise inside a building, or on a slick floor, in the near dark, or in the glare of headlights, among crowds of loud, jostling people, inside vans, or in the beds of pickup trucks, even on flights of stairs

• performing the hold and bark on seated agitators, costumed agitators or agitators equipped with bite suits or hidden sleeves instead of Schutzhund sleeves

• setting up foot races to the blind of thirty, forty or even seventy‑five yards. The helper is given enough of a head start so that he can reach the blind and freeze just before the dog arrives. If the animal can control the white‑hot desire produced by the pursuit–skidding into the blind, bouncing off the agitator without biting him and settling into a hold and bark–then there is little that will disturb its performance on trial day. (This procedure is also excellent for lending power to its bark in the blind, because it will make the dog very “pushy.”)

Our method of teaching the hold and bark produces dogs that are powerful and clean in the blind, not dogs that sit in front of the sleeve and yap politely for a bite, nor animals that bark helplessly from a distance. It produces animals that (for lack of another phrase) push in close to the agitator and “get in his face”–demanding that he move so that they can bite him.

GOAL 2: The dog will out cleanly on command.

Once the dog has a flawless hold and bark, the out is very simply taught. However, it must be well taught. If we school the out badly or incompletely, it will haunt us for the rest of the dog’s working career.

Early on in training, when the animal is still comparatively naive, we have one chance to teach it that it must release its bite on command–one opportunity to convince it that we are omnipotent and that we can reach it anywhere on the field and correct it if it disobeys. If we squander this opportunity, if the dog learns that we are actually far from omnipotent, then we will create a very persistent training problem for ourselves.

The amount of force used is critical. Too much force will inhibit the dog, killing drive and disturbing its mouth so that it bites badly or uses only a half mouth when it senses an out coming. Too little force will give the animal the opportunity to resist us, to fight the out, and as the frustrated handler gradually increases the severity of his corrections, the animal’s ability to endure them will increase as well. Soon the dog will bum as much energy fighting the out as it does fighting the decoy.

We differ from some other trainers in our desire to preserve, as much as possible, our dog’s sensitivity to us and to the correction collar. (Intensely hard animals are prized usually only by those who have never attempted to control one in bite work.) We preserve sensitivity by giving the dog little experience with corrections, so that it never has the opportunity to get used to them. When we correct, we do so sharply and effectively, so that there is not even a question of the dog resisting us. The animal quickly does as we ask and therefore undergoes few corrections. This has the effect of saving both dog and trainer a great deal of grief.

Important Concepts for Meeting the Goal

1. Back tying the dog

2. Forcing the out

3. Preventing discrimination

4. Outing the dog at distance

The handler hides in the blind behind the decoy, ready to step out and correct the dog should it bite instead of hold and bark.

Our method produces dogs that are aggressive and bold in the blind, dogs that move in close to the decoy and demand their bite. (Janet Birk’s “Jason,” Schutzhund III, FH, IPO III, UDT, WDX. We believe that Jason is the most titled Chesapeake Bay Retriever in the history of the breed.)

Back tying the dog

The first step in teaching the out is to create for ourselves a great mechanical advantage over the dog. After all, we are preparing to take the sleeve from its mouth or, more correctly, to force the dog to relinquish it. We have already spent months teaching the animal to be extraordinarily passionate and stubborn about keeping its bite against all opposition. Now we will have to overcome this stubbornness, and it will have to be done smoothly and precisely and with as little fuss as possible.

If we attempt to wrestle the sleeve from the dog by simply pulling or prying or jerking it backward off the sleeve, we often just succeed in teaching the animal to hold on more tenaciously, because we inadvertently stimulate the same oppositional reflex in it that we exploited in order to fix its mouth on the sleeve during drive work.

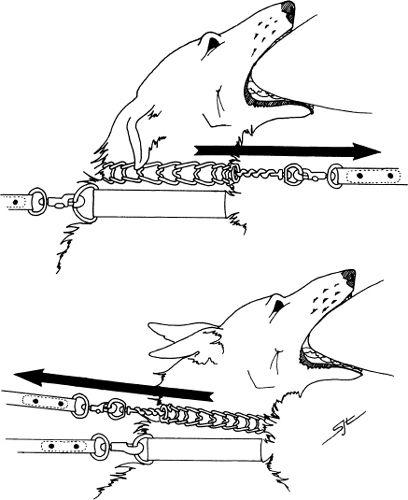

The trick is to correct into the sleeve. We begin by tethering the animal to a post or a tree on its leather agitation collar with about ten feet of line. In addition to the agitation collar, the dog wears a correction collar, which is fitted so that the leash attaches to it under its jaw. In other words, the correction collar faces forward, not back.

The handler and his assistant (who controls the correction leash) both stand outside the dog’s circle, facing it, and the decoy works in between them and the dog, being careful not to foul the correction line. If the agitator wears a left‑handed sleeve, then the assistant stands to his left, or vice versa. Thus, when the dog is on the sleeve, the correction leash will run from the collar, under the decoy’s elbow, and to the assistant. If the assistant cranes his neck a little, he can still see the dog’s mouth on the sleeve–so that he does not inappropriately correct an animal that is already outing.

The tether line and the correction leash form a straight line running directly from the tree to the assistant’s hands. With the tree to anchor it, all the force of any correction is transmitted directly to the dog’s neck. Therefore, it is possible for the assistant to administer an effective correction with precisely the amount of force he intends, neither too harsh nor too light.

The traditional method, in which the handler corrected back and away from the helper with no anchoring post, made for a very sloppy correction because the decoy’s arm absorbed a great deal of the force intended for the dog. A hard correction would simply drag both helper and dog a little closer to the handler rather than force the animal off the sleeve. The result was often that, in the end, excessive force was used in order to accomplish the out. For this reason, the back‑tie method described here is actually far kinder to the dogs.

Forcing the out

The helper begins the process by, as always, stimulating the dog. He runs back and forth around the circle described by the dog’s tether until the animal is extremely excited. Meanwhile the assistant plays the line so that both decoy and dog have the freedom to move without becoming entangled. The decoy allows a bite and then he fights the animal very strongly, pulling against the tether to fix the bite. When the dog is hard on the sleeve and very much in spirit, the decoy takes three precisely timed actions:

During training for the out, the correction must be made into the sleeve (top). The traditional method of correcting away from the sleeve (bottom) stimulates the animal’s opposition reflex and makes it bite down harder.

1. He takes a very short step toward the tree, so as to drop about six inches of slack into the tether. (Never attempt to out a dog with the animal’s mouth under tension. Remember, physical restraint stimulates the animal to bite harder.)

2. He then freezes, standing still with the sleeve across his torso, braced strongly against the dog’s attempts to drag him to and fro.

3. When he is ready, the agitator signals to the handler with a nod.

The handler gives a crisp “Out!” command–he does not shout–and at the same instant the assistant corrects the dog sharply and with enough force that the animal instantly releases the sleeve. The assistant does not pull or tug at the dog; he delivers a snapping jerk. If the first is not enough, then he delivers another crisp and slightly stronger correction, and so on. As we have already stated, the amount of force is crucial. Therefore, the person in the club with the best “hands” and the most experience should always serve as the assistant.

The dog should out and, because of all its schooling in the hold and bark, automatically rock back and begin barking. However, if it attempts to rebite, the assistant calmly corrects it again.

The instant the dog settles and lets out a bark or two, the handler allows it another bite and a vigorous fight and then slips the sleeve for it.

In other words, we reward the animal for its out with a bite and then possession of the sleeve. Too many trainers think of the out–and all the other control exercises too–as solely forced exercises, something that the dog is only resentfully compelled to do and that it will fight against tooth and claw. But there is a way to present the out to the animal so that it is in its interest to do it, not just in order to avoid a correction, but also in order to gain a bite and then possession of the sleeve.

Remember, a good fight takes two, and when the agitator freezes he robs the dog of a great part of the gratification involved in biting the sleeve. How can the animal reactivate the agitator? By letting go of the sleeve! We teach the dog to demand the helper’s participation by outing and barking. The sequence is as follows:

1. The decoy allows a bite and fights vigorously. Gratification for the dog is intense.

2. The decoy freezes. Gratification for the dog declines sharply.

3. On command, the dog outs and barks.

4. In response to the animal’s barking, the decoy allows another bite, fights vigorously and then gives the sleeve to the dog.

We must make for the dog a very clear and strong connection between the act of outing and barking and being rewarded with the sleeve. We make this connection by positioning these two events very close in time. Perhaps as little as two or three seconds elapse between the moment the dog outs and the moment it has the sleeve back in its mouth again.

The mistake trainers so frequently make is to out the dog and then make it bark for two minutes in an attempt to “bum” the idea in or, even worse, to out the dog and then heel it away from the agitator in an attempt to keep it clean. This is completely wrong because it gives the dog the idea that, by outing, it gives up the agitator and the sleeve, and loses them both.

Remember, we selected the dog for precisely its tenacity and its willingness to endure a great deal in the fight to keep possession of its prey. When it does not perceive a relationship between releasing the sleeve and then immediately getting it back again, we should not be surprised if it resists all but the most extreme force in order to stay on the sleeve. Therefore, in the beginning of out training, the sequence is bite‑out‑bite, and this chain of events is extremely rapid.

Once the dog has the idea and the out has become somewhat habitual, we can become less concerned about rewarding the out immediately and (1) gradually extend the period of time and the number of barks between the out and the rebite, and (2) perform sequences of outs, so that the animal bites and outs several times in a row before we allow it to have the sleeve.

Дата добавления: 2015-12-08; просмотров: 901;