Inguinal Herniorrhaphy.

Nonprosthetic Repair.

Local anaesthesia is entirely adequate, especially when combined with intravenous infusion of a rapid-acting, short-lasting, amnesic and anxiolytic agent such as propofol. This is the approach most commonly employed in specialty hernia clinics.

The various inguinal herniorrhaphies have a number of initial technical steps in common.

Step 1. Initial incision

Traditionally, the skin is opened by making an oblique incision between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. For cosmetic reasons, however, many surgeons now prefer a more horizontal skin incision placed in the natural skin lines. In either case, the incision is deepened through Scarpais and Camperis fasciae and the subcutaneous tissue to expose the external oblique aponeurosis. The external oblique aponeurosis is then opened through the external inguinal ring.

Step 2. Mobilization of cord structures

The superior flap of the external oblique fascia is dissected away from the anterior rectus sheath medially and the internal oblique muscle laterally. The iliohypogastric nerve is identified at this time; it can be either left in situ or freed from the surrounding tissue and isolated from the operative field by passing a haemostat under the nerve and grasping the upper flap of the external oblique aponeurosis. Routine division of the iliohypogastric nerve along with the ilioinguinal nerve is practiced by some surgeons but is not advised by most. The cord structures are then bluntly dissected away from the inferior flap of the external oblique aponeurosis to expose the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament and the iliopubic tract. The cord structures are lifted en masse with the fingers of one hand at the pubic tubercle so that the index finger can be passed underneath to meet the thumb or the fingers of the other hand. Mobilization of the cord structures is completed by means of blunt dissection, and a drain is placed around them for retraction during the procedure.

Step 3. Division of cremaster muscle

Complete division of the cremaster muscle has been common practice, especially with indirect hernias. The purposes of this practice are to facilitate identification of the sac and to lengthen the cord for better visualization of the inguinal floor. Almost always, however, adequate exposure can be obtained by opening the muscle longitudinally, which reduces the chances of damage to the cord and prevents testicular descent.

Step 4. High ligation of sac

The term high ligation of the sac is used frequently in discussign hernia repair; its historical significance has ingrained it in the descriptions of most of the older operations. For our purposes in this chapter, high ligation of the sac should be considered equivalent to reduction of the sac into the preperitoneal space without excision. The two methods work equally well and are highly effective. Some surgeons believe that sac inversion results in less pain (because the richly innervated peritoneum is not incised) and may be less likely to cause adhesive complications. Sac eversion in lieu of excision does protect intra-abdominal viscera in cases of unrecognized incarcerated sac contents or sliding hernia.

Step 5. Management of inguinal scrotal hernial sacs

Some surgeons consider complete excision of all indirect inguinal hernial sacs important. The downside of this practice is that the incidence of ischaemic orchitis from excessive trauma to the cord rises substantially. The logical sequel of ischaemic orchitis is testicular atrophy, though this presumed relationship has not been conclusively proved.

In our view, it is better to divide an indirect inguinal hernial sac in the mild portion of the inguinal canal once it is clear that the hernia is not sliding and no abdominal contents are present. The distal sac is not removed, but its anterior wall is opened as far distally as is convenient. Contrary to the opinion commonly voiced in the urologic literature, this approach does not result in excessive postoperative hydrocele formation.

Step 6. Repair of inguinal floor

Methods of repairing the inguinal floor differ significantly among the various repairs and are described separately.

Step 7. Relaxing incision

A relaxing incision is made through the anterior rectus sheath and down to the rectus abdominis, extending superiorly from the pubic tubercle for a variable distance, as determined by the degree of tension present.

Some surgeons prefer incision laterally at the superior end. This relaxing incision works because as the anterior rectus sheath separates, the various components of the abdominal wall are displaced laterally and inferiorly.

Step 8. Closure

Closure of the external oblique fascia serves to reconstruct the superficial (external) ring. The external ring must be loose enough to prevent strangulation of the cord structures yet tight enough to ensure that an inexperienced examiner will not confuse a dilated ring with a recurrence. A dilated external ring is sometimes referred to as an industrial hernia, because over the years it has occasionally been a problem during preemployment physical examinations. Scarpais fascia and the skin are closed to complete the operation.

Details of Some Specific Repairs

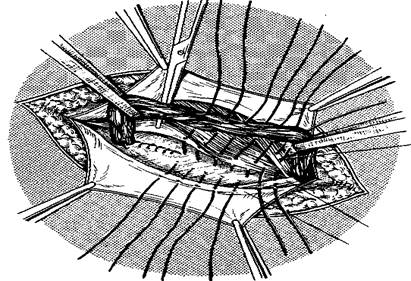

Bassini’s repair (fig. 23). Edoardo Bassini is considered the father of modern inguinal hernia surgery. The initial steps in the procedure have already described.

Bassini felt that the incision in the external oblique aponeurosis should be as superior as possible while still so that allowing the superficial external ring to be opened, reapproximation suture line created later in the operation would not be directly over the suture line of the inguinal floor reconstruction. Whether this technical point is significant is debatable.

Bassini also felt that lengthwise division of the cremaster muscle followed by resection was important for ensuring that an indirect hernial sac could not be missed and for achieving adequate exposure of the inguinal floor.

After performing the initial dissection and the reduction or ligation of the sac, Bassini began the reconstruction of the inguinal floor by opening the transversalis fascia from the internal inguinal ring to the pubic tubercle, thereby exposign the preperitoneal fat, which was bluntly dissected away from the undersurface of the superior flap of the transversalis fascia. This step allowed him to properly prepare the deepest structure in his famous “triple layer”.

|

Figure 23 – Inguinal herniorrhaphy: Bassini’s repair

Figure 23 – Inguinal herniorrhaphy: Bassini’s repair

The first stitch in Bassini’s repair includes the triple layer superiorly and the periosteum of the medial side of the pubic tubercle, along with the rectus sheath. In current practice, however, most surgeons try to avoid the periosteum of the pubic tubercle so as to decrease the incidence of osteitis pubis. The repair is then continued laterally, and the triple layer is secured to the reflected inguinal ligament (Poupartis ligament) with nonabsorbable sutures. The sutures are continued until the internal ring is closed on its medial side. A relaxing incision was not part of Bassini’s original description but now is commonly added.

Concerns about injuries to neurovascular structures in the preperitoneal space as well as to the bladder led many surgeons, especially in North America, to abandon the opening of the transversalis fascia. The unfortunate consequence of this decision is that the proper development of the triple layer is severely compromised. In lieu of opening the floor, a forceps (e.g., an Allis clamp) is used to grasp tissue blindly in the hope of including the transversalis fascia and the transversus abdominis. The layer is then sutured, along with the internal oblique muscle, to the reflected inguinal ligament as in the classic Bassini’s repair. The structure grasped in this modified procedure is sometimes referred to as the conjoined tendon, but this is not correct because of the variability in what is actually grasped in the clamp.

Shouldice’s repair (fig. 24).The repair is started at the pubic tubercle by approximating the iliopubic tract laterally to the undersurface of the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis. The suture is continued laterally, approximating the iliopubic tract to the medial flap, which is made up of the transversalis fascia, the internal oblique muscle, and the transversus abdominis. Eventually, four suture lines are developed from the medial flap. The continuous suture is extended to the internal ring, where the lateral stump of the cremaster muscle is picked

Figure 24 – Inguinal herniorrhaphy: Shouldice’s repair

up to form a new internal ring. Next, the direction of the suture is reversed back toward the pubic tubercle, approximating the medial edges of the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis to Poupartis ligament, and the wire is tied to itself and then to the first knot. Thus, two suture lines are formed by the first suture. The second wire suture is started near the internal ring, approximating the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis to a band of external oblique aponeurosis superficial and parallel to Poupartis ligament – in effect, creating the second, artificial Poupartis ligament. This third suture line ends at the pubic crest. The suture is then reversed, and the fourth suture line is constructed in a similar manner, superficial to the third line.

McVay’s repair. This operation is similar to the Bassini’s repair, except that it uses Cooperis’s ligament instead of the inguinal ligament for the medial portion of the repair.

Interrupted sutures are placed from the pubic tubercle laterally along Cooperis’s ligament, progressively narrowing the femoral ring; this constitutes the most common application of the repair – namely, treatment of a femoral hernia .The last stitch in Cooperis’s ligament is known as a transition stitch and includes the inguinal ligament. This stitch has two purposes:(1) to complete the narrowing of the femoral ring by approximating the inguinal ligament to Cooperis’s ligament, as well as to the medial tissue, and (2) to provide a smooth transition to the inguinal ligament over the femoral vessel so that the repair can be continued laterally (as in a Bassini repair). Given the considerable tension required to bridge such a large distance, a relaxing incision should always be used. In the view of many authorities, this tension results in more pain than is noted with other herniorrhaphies and predisposes to recurrence. For this reason, the McVay’s repair is rarely chosen today, except in patients with a femoral hernia or patients with a specific contraindication to mesh repair.

Girard’s repair. In these operations it is proposed to attach the edges of the internal oblique muscle and transverse muscle of abdomen to the inguinal ligament over the spermatic duct. The aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle sutured by second layer of the suture. Excess of the aponeurosis is fixed to the muscle in the form of duplication.

Spasokukotsky’s repair. Proposed to suture the edges of the internal oblique muscle and transverse muscle of abdomen with aponeurosis of the external oblique muscles by signle-layer interrupted suture.

Martynov’s repair. Proposed the fixation to the Poupartis ligament the internal edge of the external oblique muscle aponeurosis without muscles. External edge of the aponeurosis is sutured over internal in the form of duplication.

Kimbarovsky’s repair. Based on the principles of joining similar tissues, proposed special suture: Sutures placed on 1 cm from the edge of the external oblique abdominal muscle aponeurosis, grasped the part of the internal oblique and transverse muscle of abdomen. After that, aponeurosis is sutured one more time from behind to the front and attached to the Poupartis ligament.

Kukudganov’s repair. Proposed to restore back wall of inguinal interval. Sutures are placed between the Couperis ligament, direct abdominal muscle and aponeurosis of the transversal muscle.

Postempsky’s repair (fig. 25). Proposed the closure of inguinal interval with the lateralization moving of spermatic duct. The plastic narrowing of internal inguinal ring of to 0.8 cm is the important stage of this modification. On occasion, when internal and external inguinal rings are in one plaine, the spermatic duct is displaced in lateral direction by transversal incision of the oblique and transversus muscles.

|

Figure 25 – Inguinal herniorrhaphy:

Postempsky’s repair

Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Alloplastic Repair

Lichtenstein’s repai. The first five steps of a Lichtenstein’s repair are very similar to the first five steps of a conventional anterior nonprosthetic repair, but there are certain technical points that are worthy of emphasis. The external oblique aponeurosis is generously freed from the underlying anterior rectus sheath and internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis in an avascular zone from a point at least 2 cm medial to the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine laterally. Blunt dissection is continued in this avascular zone from the region lateral to the internal ring to the pubic tubercle along the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament and the iliopubic tract. As a continuation of this same motion, the cord with its cremaster covering is swept off the pubic tubercle and separated from the inguinal floor. Besides mobilizing the cord, these maneuvers create a large space beneath the external oblique aponeurosis that can eventually be used for prosthesis placement. The ilioinguinal nerve, the external spermatic vessels and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve all remain with the cord structures.

For indirect hernias, the cremaster muscle is incised longitudinally, and the sac is dissected free and reduced into the preperitoneal space. Theoretically, this operation could be criticized on the grounds that if the inguinal floor is not opened, an occult femoral hernia might be overlooked. To date, however, an excessive incidence of missed femoral hernias has not been reported. In addition, it is possible to evaluate the femoral ring via the space of Bogro’s through a small opening in the canal floor.

Direct hernias are separated from the cord and other surrounding structures and reduced back into the preperitoneal space. Dividing the superficial layers of the neck of the sac circumferentially – which, in effect, opens the inguinal floor – usually facilitates reduction and helps maintain it while the prosthesis is being placed? This opening in the inguinal floor also allows the surgeon to palpate for a femoral hernia. Sutures can be used to maintain reduction of the sac, but they have no real strength in this setting; their main purpose is to allow the repair to proceed without being hindered by continual extrusion of the sac into the field, especially when the patient strains.

Placement of prosthesis. A mesh prosthesis is positioned over the inguinal floor. The medial end is rounded to correspond to the patients particular anatomy and secured to the anterior rectus sheath at least 2 cm medial to the pubic tubercle. A continuous suture of either nonabsorbable or long-lasting absorbable material should be used. Wide overlap of the pubic tubercle is important to prevent the pubic tubercle recurrences all too commonly seen with other operations. The suture is continued laterally in a locking manner, securing the prosthesis to either side of the pubic tubercle (not into it) and then to the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament. The suture is tied at the internal ring.

Creation of shutter valve. A slit is made at the lateral end of the mesh in such a way as to create two tails, a wider one (approximately two thirds of the total width) above and a narrower one below. The tails are positioned around the cord structures and placed beneath the external oblique aponeurosis laterally to about the anterior superior iliac spine, with the upper tail placed on top of the lower. A signle interrupted suture is placed to secure the lower edge of the superior tail to the lower edge of the inferior tail effect, creating a shutter valve. This step is considered crucial for preventing the indirect recurrences occasionally seen when the tails are simply reapproximated. The same suture incorporates the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament so as to create a domelike buckling effect over the direct space, thereby ensuring that there is no tension, especially when the patient assumes an upright position.

Securing of prosthesis. A few interrupted sutures are placed to attach the superior and medial aspects of the prosthesis to the underlying internal oblique muscle and rectus fascia. On occasion, the iliohypogastric nerve, which courses on top of the internal oblique muscle, penetrates the medial flap of the external oblique aponeurosis. In this situation, the prosthesis should be slit to accommodate the nerve. The prosthesis can be trimmed in situ, but care should be taken to maintain enough laxity to allow for the difference between the supine and the upright positions, as well as for possible shrinkage of the mesh.

Дата добавления: 2015-07-04; просмотров: 1800;