THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF ALLIED FORCE

Admittedly, there is much to be said of a positive nature about NATO’s air war for Kosovo. To begin with, it did indeed represent the first time in which air power coerced an enemy leader to yield with no friendly land combat action whatsoever.[509]In that respect, the air effort’s conduct and results well bore out a subsequent observation by Australian air power historian Alan Stephens that “modern war is concerned more with acceptable political outcomes than with seizing and holding ground.”[510]

It hardly follows from this, of course, that air power can now “win wars alone” or that the air‑only strategy ultimately adopted by the Clinton administration and NATO’s political leaders was the wisest choice available to them. Yet the fact that air power prevailed on its own despite the multiple drawbacks of a reluctant administration, a divided Congress, an indifferent public, a potentially fractious alliance, a determined enemy, and, not least, the absence of a credible NATO strategy surely testified that the air weapon has come a long way in recent years in its relative combat leverage compared to other, more traditional force elements. Thanks to the marked improvements in precision attack and battlespace awareness, unintended damage to civilian structures and noncombatant fatalities were kept to a minimum, even as air power plainly demonstrated its coercive potential.

In contrast to Desert Storm, the air war’s attempts at denial did not bear much fruit in the end. Allied air attacks against dispersed and hidden enemy forces were largely ineffective, in considerable part because of the decision made by NATO’s leaders at the outset to forgo even the threat of a ground invasion. Hence, Serb atrocities against the Kosovar Albanians increased even as NATO air operations intensified. Yet ironically, in contrast to the coalition’s ultimately unsuccessful efforts to coerce Saddam Hussein into submission, punishment did seem to work against Milosevic, disconfirming the common adage that air power can beat up on an adversary indefinitely but rarely can induce him to change his mind.

Although these and other operational and tactical achievements were notable in and of themselves and offered ample grist for the Kosovo “lessons learned” mill, the most important accomplishments of Allied Force occurred at the strategic level and had to do with the performance of the alliance as a combat collective. First, notwithstanding the charges of some critics to the contrary, NATO clearly prevailed over Milosevic in the end. In the early aftermath of the air war, more than a few observers hastened to suggest that NATO’s bombing had actually caused precisely what it had sought to prevent. Political scientist Michael Mandelbaum, for example, portrayed Allied Force as “a military success and political failure,” charging that while it admittedly forced a Serb withdrawal from Kosovo, the broader consequences were the opposite of what NATO’s chiefs had intended because the Kosovar Albanians “emerged from the war considerably worse off than they had been before.”[511]Another charge voiced by some was that as Allied Force wore on, NATO watered down the demands it had initially levied on Milosevic at Rambouillet. As early as the air war’s 12th day, this charge noted, NATO merely stipulated that Kosovo must be under the protection of an “international” security force, whereas at Rambouillet, it had insisted on that presence being a NATO force.[512]

There is no denying that the Serb ethnic cleansing push accelerated after Operation Allied Force began. It is even likely that the air effort was a major, if not determining, factor behind that acceleration. Yet it seems equally likely that some form of Operation Horseshoe, as the ethnic cleansing campaign was code‑named, would have been unleashed by Milosevic in any event during the spring or summer of 1999. Indeed, what a Serb general was later said by SACEUR to have forecast as a “hot spring” in which “the problem of Kosovo… will definitely be solved” commenced more that a week before the start of Allied Force, when VJ and MUP strength in and around Kosovo was increased by 42,000 troops and some 1,000 heavy weapons–even as the Rambouillet talks were under way.[513]Administration defenders are on solid ground in insisting that the ethnic cleansing had already begun and that had NATO not finally acted when it did, upward of a million Kosovar refugees may well have been left stranded in Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro, with no hope of returning home.[514]

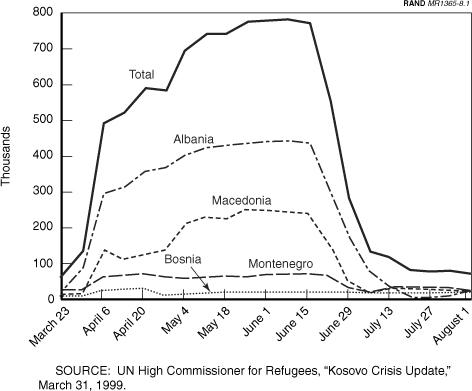

Although NATO’s air strikes were unable to halt Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing campaign before it had been essentially completed, they did succeed in completely reversing its effects in the early aftermath of the cease‑fire. Within two weeks of the air war’s conclusion, more than 600,000 of the nearly 800,000 ethnic Albanian and other refugees had returned home. By the end of July, barely one month after the cease‑fire, only some 50,000 displaced Kosovar Albanians still awaited repatriation (see Figure 8.1). By any reasonable measure, Milosevic’s bowing to NATO reflected a defeat on his part, and his accession to the cease‑fire left him worse off than he would have been had he accepted NATO’s conditions at Rambouillet. Under the terms of Rambouillet, Serbia would have been permitted to keep 5,000 of its “security forces” in Kosovo. Thanks to the settlement ultimately reached before the cease‑fire, however, there are now none. Moreover, on the eve of Operation Allied Force, Milosevic had insisted as a point of principle that not a single foreign troop would be allowed to set foot on Kosovo soil. Today, with some 42,000 KFOR soldiers from 39 countries performing daily peacekeeping functions, Kosovo is an international protectorate safeguarded both by the UN and NATO, rendering any continued Serb claim to sovereignty over the province a polite fiction. At bottom, as NATO’s Secretary General, Javier Solana, declared in a retrospective commentary on the experience, the alliance “achieved every one of its goals” in forcing a Serb withdrawal from Kosovo.[515]Whether or not one chooses to call that outcome a “victory” entails what Karl Mueller has characterized as “a semantic exercise that should only really matter to social scientists seeking to code the event for data analysis.”[516]

Figure 8.1–Refugee Flow

Second, NATO showed that it could operate successfully under pressure as an alliance, even in the face of constant hesitancy and reluctance on the part of many of the member‑states’ political leaders. For all the air war’s fits and starts and the manifold frustrations they caused, the alliance earned justified credit for having done remarkably well in a uniquely challenging situation. In seeing Allied Force to a successful conclusion, NATO did something that it had been neither created nor configured to do. Indeed, it might well have been easier for Washington and SACEUR to elicit NAC approval to grant border‑crossing authority at the brink of a NATO–Warsaw Pact showdown during the height of the cold war than to get 19 post–cold war players on board for an offensive operation conducted to address a problem that threatened no member’s most vital security interests. As General Clark later recalled, the “ultimate proof” of the air war’s success was that NATO realized its “ability to maintain alliance cohesion despite all the pressures of fighting a conflict, at the same time bringing in new members, and then going into Kosovo itself on an extended and uncertain campaign–uncertain in that there [was] no fixed exit date.”[517]

Reflecting on the air war experience a year later, Admiral James Ellis, the commander of the U.S. contribution to Allied Force, observed that during the final days leading up to March 24, it was a question not of how the bombing effort would be conducted so much as whether it would take place at all. Before Rambouillet, the challenge had been to compel Milosevic to do something. Afterward, it became to compel him to stop doing something. Ellis speculated that had the allies known from the outset that they were signing up for a 78‑day campaign, they might easily have declined the opportunity forth‑with. Unlike the ad hoc group of nations that fought Desert Storm as a solidly united front, NATO was not a coalition of the willing but rather a loose defensive alliance of 19 democracies. They were all strongly inclined to march to different drummers, and all had varying commitments to grappling–at least militarily–with humanitarian crises in which they had no clear national security stake.[518]

As the bombing entered its third month without a clear end in sight, Ellis feared that allied cohesion might collapse within three weeks unless something of a game‑changing nature occurred, such as a drastic move by Milosevic to alter the stakes or a firm U.S. decision to accede to a ground‑invasion option. Offsetting that fear, however, was his belief that the allies were finally beginning to recognize and accept the need to come to terms with some thorny operational issues such as granting approval to attack electrical power and other key infrastructure targets. That took time, Ellis said, but the fact that it finally occurred constituted a signal that the alliance was slowly learning how to do what needed to be done.

Finally, for all the criticism that was directed against some of the less steadfast NATO members for their rearguard resistance and questionable loyalty while the air war was under way, even the Greek government held firm to the very end, despite the fact that more than 90 percent of the Greek population supported the Serbs rather than the Kosovar Albanians–and held frequent large‑scale street demonstrations to show that support.[519]True enough, there remain many unknowns about the outlook for NATO’s steadfastness in any future confrontation along Europe’s eastern periphery. Yet NATO was able to maintain the one quality that was essential for the success of Allied Force: its cohesion and integrity as a fighting collective. The lion’s share of the credit for that, suggested Air Marshal Sir John Day, belongs to NATO Secretary General Solana, who, in what Day called a “brilliant” performance, showed both leadership and courage in the face of continuous U.S. pushing and an equally continuous reluctance on the part of many allies to go along.[520]

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1252;