PROBLEMS AT THE COALITION LEVEL

In their joint statement to the Senate Armed Services Committee after the war ended, Secretary Cohen and General Shelton rightly insisted that Operation Allied Force “could not have been conducted without the NATO alliance and without the infrastructure, transit and basing access, host‑nation force contributions, and most important, political and diplomatic support provided by the allies and other members of the coalition.”[408]Yet the conduct of the air war as an allied effort, however unavoidable it may have been, came at the cost of a flawed strategy that was further hobbled by the manifold inefficiencies that were part and parcel of conducting combat operations by committee.

Those inefficiencies did not take long to manifest themselves. During the air war’s first week, NATO officials reported that up to half of the proposed strike missions had been aborted due to weather and “other considerations,” the latter, in many cases, being the refusal of some allies to approve certain target requests.[409]Indeed, the unanimity principle made for a rules‑of‑engagement regime that often precluded the efficient use of air power. Beyond that, there was an understandable lack of U.S. trust in some allies where the most important sensitivities were concerned. The Pentagon withheld from the allies mission specifics for literally hundreds of sorties that entailed the use of F‑117s, B‑2s, and cruise missiles, to ensure strict U.S. control over those U.S.‑only assets and to maintain a firewall against leaks from any allies who might compromise those operations.[410]

In addition to the natural friction created by NATO’s committee approach to target approval, the initial reluctance of its political leaders to countenance a more aggressive air campaign produced a resounding failure to capitalize on air power’s potential for taking down entire systems of enemy capability simultaneously. In his first interview after Allied Force had begun six weeks earlier, the air component commander, USAF Lieutenant General Michael Short, was frank in airing his sense of being constrained by the political limits imposed by NATO, pointing out that the graduated campaign was counter to all of his professional instincts.[411]Short further admitted that he was less an architect of the campaign than its implementor. He was particularly critical of NATO’s unwillingness to threaten a ground invasion from the start, noting that that failure was making it doubly difficult for NATO pilots to identify their targets because of the freedom it had given VJ forces to disperse and hide their tanks and other vehicles.

Finally, Operation Allied Force was hampered by an inefficient target planning process. Because NATO had initially expected that the bombing would last only a few days, it failed to establish a smoothly running mechanism for target development and review until late April. The process involved numerous planners in the Pentagon and elsewhere in the United States, at SHAPE in Belgium, at USEUCOM headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany, and at the CAOC in Vicenza, Italy, with each participant logging on daily to the earlier‑noted secure digitized military computer network called SIPRNET.

Daily target production began at the U.S. Joint Analysis Center at RAF Molesworth, England, where analysts collated and transmitted the latest all‑source intelligence, including overhead imagery from satellites and from Air Force Predator, Navy Pioneer, and Army Hunter UAVs. Because the United States commanded the largest number of intelligence assets both in the theater and worldwide by a substantial margin, it proposed most of the targets eventually hit, although other allies made target nominations as well.[412]With the requisite information in hand, target planners at SHAPE and USEUCOM would then begin assembling target folders, conducting assessments of a proposed target’s military worth, and taking careful looks at the likelihood of collateral damage. In addition, lawyers would vet each proposed target for military significance and for conformity to the law of armed conflict as reflected in the Geneva Conventions.

Once ready for review and forwarding up the chain of command for approval, these target nominations would then go to the Joint Target Coordination Board for final vetting. That board’s recommendations would then go to Admiral James Ellis, commander of Joint Task Force Noble Anvil and commander in chief, Allied Force Southern Europe (CINCSOUTH), and his staff in Naples, who would review all target nominations and forward his recommendations to General Clark, who in turn would personally review each target to ensure that it fit the overall guidelines authorized by the NAC.[413]

Approved targets would then go back to Admiral Ellis, who would task both the USAF’s 32nd Air Operations Group at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, and the 6th Fleet command ship deployed in the Mediterranean to develop target folders. The 32nd AOG would assign multiple aim points per nominated target set and multiple weaponeering solutions for a broad spectrum of air‑delivered munitions. The 6th Fleet planning staff would do the same for TLAM targets.[414]As one might expect, this exceptionally time‑consuming process greatly limited the number of potential targets that could be struck at any given time. Moreover, even after these multiple hurdles had been crossed, an approved target could still be countermanded or withheld by U.S. or NATO political authorities.[415]

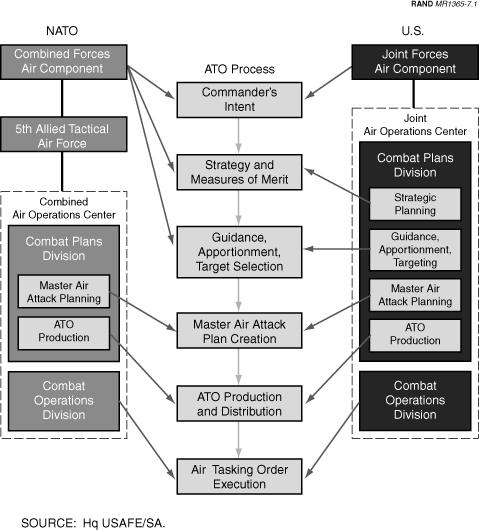

Further compounding the unavoidable inefficiency of this multistage and circuitous process, two parallel but separate mechanisms for mission planning and air tasking were used (see Figure 7.1). As noted earlier, any U.S.‑specific systems involving special sensitivities, such as the B‑2, F‑117, and cruise missiles, were allocated by USEUCOM rather than by NATO, and the CAOC maintained separate targeting teams for USEUCOM and NATO strike planning. This dual ATO arrangement meant increased burdens on the planning system to execute workarounds in cases where automated mission planning systems could not support the dual process, as well as added complications in airspace control planning created by the presence of low‑observable aircraft, the limited use of IFF systems in some cases, and the absence of a single, integrated air picture for all participants. Although the use of stealthy aircraft in this dual‑ATO arrangement was dealt with by time and space deconfliction, it nonetheless made for problems for allies who were not made privy to those operations, yet who needed information about them in the interest of their own situation awareness and force protection.[416]Commenting on the friction that was inevitably occasioned by this cumbersome system, General Short recalled in hindsight that he was constantly having to tell allied leaders to “trust me” regarding what U.S. assets would be doing and that he would have preferred to find a way of ensuring that the daily allied air operations schedule reflected those U.S. systems in some usable way. As it was, their absence led on occasion to some significant force deconfliction problems, such as U.S. aircraft suddenly showing up on NATO AWACS displays when and where they were not expected.[417]

Figure 7.1–Operation Allied Force Planning and Implementation

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1377;